European Journal of Family Business (2022) 12, 1-123

Family Business Resilience: The Importance of Owner-Manager’s Relational Resilience in Crisis Response Strategies

Matti Schulzea*, Jana Böversa

aBielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany

Research paper. Received: 2022-5-4; accepted: 2022-12-15

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10

KEYWORDS

Crisis management, Digital transformation, Family business, Owner-managers, Resilience

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10

PALABRAS CLAVE

Gestión de crisis, Transformación digital, Empresa familiar, Propietarios-gestores, Resiliencia

Abstract The COVID19 pandemic has disclosed the compelling necessity for businesses to develop and maintain a high resilience to survive the constantly changing environment they operate in and the rising number of crises they face. Our study sheds light on the resilience of owner-managed family businesses, with a special focus on different levels within and beyond the organization, by analyzing digitalization efforts as one form of strategic response to a crisis. More precisely, building on an extensive explorative multiple case study, we explore how and why owner-managed family businesses differ regarding their resilience and the implications this has for their crisis management. We contribute both to the literature on resilience and to research on family business strategies by showing differences in crisis response related to different levels of family business resilience and the special role of the owner-manager.

Determinantes del pago de dividendos en empresas españolas no cotizadas, familiares y no familiares

Resumen La pandemia de COVID19 ha puesto de manifiesto la imperiosa necesidad de que las empresas desarrollen y mantengan una elevada resiliencia para sobrevivir en el entorno en constante cambio en el que operan y hacer frente al creciente número de crisis a las que se enfrentan. Nuestro estudio arroja luz sobre la resiliencia de las empresas familiares gestionadas por sus propietarios, con especial atención a los diferentes niveles, dentro y fuera de la organización, mediante el análisis de los esfuerzos de digitalización como una forma de respuesta estratégica a una crisis. Más concretamente, a partir de un amplio estudio exploratorio de casos múltiples, exploramos cómo y por qué las empresas familiares gestionadas por sus propietarios difieren en cuanto a su resiliencia y las implicaciones que esto tiene para su gestión de crisis. Contribuimos tanto a la literatura sobre resiliencia como a la investigación sobre las estrategias de las empresas familiares al mostrar las diferencias en la respuesta a las crisis relacionadas con los distintos niveles de resiliencia de las empresas familiares y el papel especial del propietario-administrador.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i2.14657

Copyright 2022: Matti Schulze, Jana Bövers

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author:

E-mail: matti.schulze@googlemail.com

1. Introduction

Family businesses face special challenges regarding business survival and longevity. When managing the trade-off between continuity and adaptability (Campopiano et al., 2019), they always have to consider both the family side and the business side (Sharma & Salvato, 2015). Drawing upon the notion of longevity, scholars are increasingly exploring the long-term survival of family businesses in disruptive environments (Antheaumene et al., 2013; Bövers & Hoon, 2021; Riviezzo et al., 2015).

To address crisis-induced changes in technology, markets, or society, family firms often have to be highly resilient and adapt their business strategy (Stafford et al., 2013). Here, resilience refers to the ability of organizations to avoid, absorb, respond to, and recover from situations that could threaten their existence (Lengnick-Hall & Beck 2005). In particular, the COVID19-induced crisis has been a challenge for many family firms, forcing them to adapt, often leading to organizational and strategic transformations (Kraus et al., 2020). While previous research has started to reveal how family businesses generally respond to crises (Calabrò et al., 2021), we know surprisingly little about individual differences in family businesses’ efforts to respond to crises such as the COVID19 pandemic. On this basis, we understand crisis management as the strategic response to a situation that threatens business continuance (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). Building on that, our aim is to answer the question of how and why owner-managed family businesses differ regarding their resilience and the implications this has for their crisis management.

Evaluating the effects of family dynamics on business strategy and behavior is of special importance, as family firms are often seen as unwilling to change and strategy in family businesses is different from nonfamily firms (e.g., Daspit et al., 2017; Nordqvist & Melin, 2010; Sharma et al., 1997). Nevertheless, recent studies showed that the COVID19 crisis made family firms unlock their innovation potential (Leppäaho & Ritala, 2022) and use their adaptive capacity to overcome a crisis (Soluk et al., 2021). In addition, the long-term existence of family firms relies on their relational adaptation abilities (Williams et al., 2017). This describes their ability to manage interactions, especially outside of the organization itself. In what follows, we consider family businesses as businesses in which the family has ownership control and a hands-on involvement in the management of the business (Astrachan et al., 2002; Shanker & Astrachan, 1996) and especially focus on those companies with family involvement in management and leadership (Amit & Villalonga, 2014).

To extend the understanding of family business crisis management, we focus on individual differences in the family business owner-manager’s strategic decision making as a response to a crisis, considering business adaptation and transformation as central mechanisms of business resilience. More specifically, we focus on the use of technology as a strategic response to the COVID19-induced crisis. We consider those businesses exhibiting long-term digital transformation processes to have succeeded in responding to a crisis in contrast to a short-term digital adaptation (which is often a precondition to the digital transformation). Furthermore, we adopt a more nuanced view on family business resilience in going beyond organizational resilience and the functioning of the business family (Calabrò et al., 2021), considering resilience as a multi-level construct. Hence, to enhance the understanding of family business owner-manager’s resilience, we conduct a multiple case study based on a vast data set spanning interviews, documents, observations, and website analysis of 141 businesses.

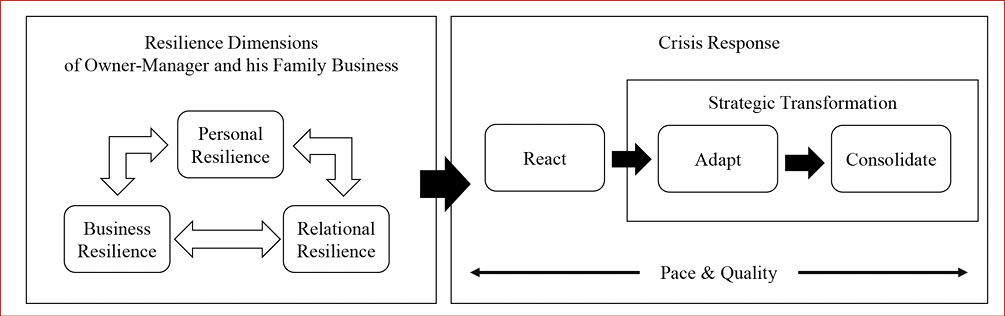

Our extensive qualitative study reveals that all family businesses under study were affected equally by the crisis. However, they largely vary in their ability to adapt and even thrive and innovate as a reaction to the crisis. This depends on the manifestation of resilience in their business, influencing the pace and quality of their crisis response.

We contribute to existing research in various ways. First, we enhance research on resilience by empirically extending the understanding of resilience and identifying three dimensions of resilience, namely personal, business, and relational resilience, which mutually influence each other. In doing so, we especially highlight the multidimensionality of the resilience concept, helping to refine existing conceptualizations and diverging research (Ventura et al., 2020). We also extend the understanding on the relationship between these dimensions (Santoro et al., 2021). Especially the relational dimension of resilience offers rich insights into the functioning of family businesses after a crisis, extending the relational benefits of family business owner-managers beyond the family and the business. Reaching high levels of relational resilience, especially through resource sharing and knowledge sharing, highly enhances the quality of crisis response.

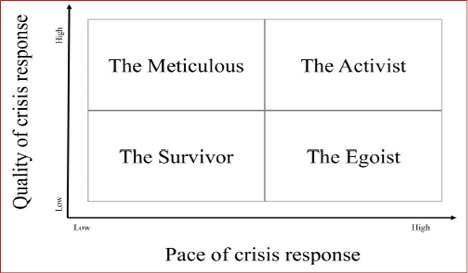

Second, we therefore add to the research on crisis response, as we show that the different levels of resilience have vast consequences on the way family businesses react to crises. This reaction can be divided into three modes: react, adapt, and consolidate. Further, depending on the owner-managers and their family business, there are large differences in the pace and quality of digital transformation and hence the strategic response. Our data suggest a link between relational resilience and the quality of the crisis response, highlighting the importance of the relational aspect of resilience and especially identifying the owner-managers’ personal ties outside the business family as making a significant difference. Thereby we also shed light on the relationship between resilience and strategy.

Third, in showing the multiple ways through which they are able to increase resilience, our study also adds to research on the central role of owner-managers in family businesses, especially during crises. We found four different types of owner-managers and their family businesses, enriching our understanding of how strategic transformation in family businesses can be reached.

Lastly, our study has several practical implications for family businesses, their owner-managers and policy makers. Our findings especially highlight the inter-connectedness between these players, leading to the overall recommendations for owner-managers to recognize the advantages of business ecosystems and to actively position themselves within them to facilitate strategic transformation.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Owner-managed family businesses and resilience

Although there are multiple conceptual elements to define and classify a family business (Hernández-Linares et al., 2017), we suppose active family involvement in management and leadership is an essential defining feature of family firms (Amit & Villalonga, 2014). As a result, this involvement allows the family to directly transfer their own values, goals, and practices to the business and to immediately influence its decision-making processes and organizational behavior (Salvato et al., 2019). Research has shown that family ownership creates value only when it is combined with certain forms of family management and control (Amit & Villalonga, 2014). As a consequence, we focus on owner-managers in family businesses and their response to a crisis. Given their special role as owners, they are granted ultimate property and residual rights and can thereby exert superior influence on the strategy of their businesses (Schulze & Zellweger, 2021). In addition, in a family business, owners face the challenge of positioning themselves toward the family business’s need for continuity and the need to adapt and change when needed to hand down the company to the next generation (Erdogan et al., 2020; Lorenzo-Gómez, 2020).

In times of crisis, business families have been found capable of mobilizing their specific bundle of resources to keep their business operating, lending superior resilience to family firms (Amann & Jaussaud, 2012; Calabrò et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2020). More precisely, research has shown family businesses’ ability to leverage their family’s social capital and patient financial capital, which can make a difference in times of crisis, making the family the backbone of family business resilience in such times (Calabrò et al., 2021). The growing amount of environmental turbulence has led to an increasing value of resilience (Zhao et al., 2016).

Here, resilience refers to how firms adjust, adapt, and reinvent their business models in a changing environment (Sharma & Salvato, 2015). Lengnick-Hall and Beck (2005) defined resilience as the ability of organizations to avoid, absorb, respond to, and recover from situations that could threaten their existence. As one of the main objectives of family firms is their long-term survival, transferring their business to subsequent generations (Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011), resilience is especially important in this type of firm. Family-owned and managed businesses with high resilience develop idiosyncratic ways of responding to exogenous shocks (Danes et al., 2009; Haynes et al., 2019; Herbane, 2015).

Previous research has illustrated that family members’ abilities to access resources, make decisions, and take actions in the presence of unforeseen circumstances are critical to family business sustainability (Danes et al., 2009). Therefore, family business resilience is a special type of resilience that reflects “the reservoir of individual and family resources that cushions the family business against disruptions” (Brewton et al., 2010). Additionally, based on a review of the paradigm of resilience in family businesses by Ventura et al. (2020), we understand resilience as a multi-level concept, with different organizational levels mutually influencing each other and cumulatively adding up to the overall resilience of the business (Anwar et al., 2021; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011).

Especially in owner-managed businesses, personal resilience in the form of the owner-managers’ resilience is particularly important to business survival (Ghobakhloo & Tang, 2013; Herbane, 2019; Kevill et al., 2017). Owner-managers need to be able to look for alternatives under adverse conditions and to deal with complex situations, identifying solutions (Renko et al., 2021; Santoro et al., 2021). Whereas owner-managers can be present in both family and nonfamily firms (Chrisman et al., 2016), owners of the former usually pursue goals that involve increasing both financial and socioemotional wealth (Chrisman et al., 2016; Rousseau et al., 2018) and exhibit stronger stewardship toward the firm (Hadjielias et al., 2021; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006). Despite the limited insights into the influence of owner-manager resilience on family business resilience, long-term family ownership orientation and the desire to transfer the business to future generations have been identified as providing the social, financial, and emotional capital required to successfully cope with emergencies (Calabrò et al., 2021; Salvato et al., 2020).

On the next level, we follow Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal (2016) to define organizational resilience as a set of capabilities that equip the business with tendencies that can facilitate its reaction to unexpected disruptions. This entails positive adjustments made by the firm under adversity, which mainly involve effective coordination and knowledge integration (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005; Williams et al., 2017). These adjustments are positively influenced by relational coordination in the form of effective communication and integration across roles and functions (Anwar et al., 2021). This is specified through the three key domains of resilience: communication, problem solving, and adaptability (Burnard & Bhamra, 2011).

As argued above, family business resilience is special regarding the necessity of considering the connection between the family and the business and the importance of relational ties within and beyond the business. However, studies on resilience have focused largely on the abilities and capabilities of individuals or businesses. There is some research in psychology on resilience as a relational dynamic (Jordan, 1992). Although the few existing studies have highlighted resilience through networks as a meaningful strategy in handling crises (Schwaiger et al., 2022), more research on relational resilience in business and management is needed. Studies on resilience in family businesses focus on family capital (human, social, and financial), with social capital being the most important resource for overcoming a crisis, particularly in the form of strong social relationships (Mzid et al., 2019) that can be understood as an antecedent of organizational resilience (Herbane, 2019). In line with that, a literature review by Chrisman, Chua, and Steier (2011) points out that social capital, as a factor of family business resilience, can be caused by social exchange and thus should be further investigated.

Additionally, cooperation, networking, and the embeddedness of one firm increase the level of overall resilience (Dahles & Susilowati, 2015; Schwaiger et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2021) and that community can be seen as a strategic resource (Gibson et al., 2021). Furthermore, a family firm’s embeddedness in an ecosystem can be highly beneficial (Bichler et al., 2022). Research has mainly focused on the collaboration between firms and their interactions in a network (Chesbrough & Appleyard, 2007; Lorenzoni & Baden-Fuller, 1995; Wulf & Butel, 2017). In particular, the idea of achieving synergies by sharing resources is the main driver behind collaborative efforts between organizations (Ahuja, 2000; Arya & Lin, 2007). Additionally, the exchange of knowledge is seen as a success factor of these collaborations (Wulf & Butel, 2017). Overall, these mechanisms enable businesses to build long-lasting competitive advantages (Albers et al., 2016; Lorenzoni & Baden-Fuller, 1995; Rong & Shi, 2015). Other research streams emphasize a more “holistic view of the business network and the relationships and mechanisms that are shaping it, while including the roles and strategies of the individual actors that are a part of these networks” (Anggraeni et al., 2007, p. 11), implying the high importance of relational resilience. Hence, firms are no longer isolated, acting alone in a market between and against their competitors, but are integrated in an ecosystem where organizations are connected (Brass et al., 2004), striving due to these connections (Makinen & Dedehayir, 2012).

2.2. Strategic response to change in family businesses

As argued above, we consider family business owner-manager’s strategic decision as a response to a crisis, with a special focus on business adaptation and transformation as central mechanisms of business resilience. Therefore, resilience can be understood as a prerequisite to strategy, both internalized in the owner-managers and their family businesses.

Strategic management research has focused largely on nonfamily businesses, especially considering performance and competitive strategies (Furrer et al., 2008; Hoskisson et al., 1999). Coming from a legitimate discussion of whether these results can be applied to family business research, Astrachan (2010) formulated a multidimensional research agenda for strategy in family business. Thus, evaluating the effects of family dynamics on business strategy and behavior is of special importance, as family firms are often seen as unwilling to change, and strategy in family businesses has to be seen from a different perspective (e.g., Daspit et al., 2017; Nordqvist & Melin, 2010; Sharma et al., 1997). In contrast to these expectations, several studies demonstrate family businesses’ responsiveness to strategic change, resulting in a competitive advantage (Memili et al., 2010) and the sustainability of the firms (Pieper, 2010). One reason for this is their ability to manage the tension between tradition and future business requirements (Erdogan et al., 2020).

To keep pace with rapid and disruptive changes (Johnson et al., 2009), family firms can mobilize new, modified, or adjusted strategic options, for example, regarding products, internationalization, or innovation (Aronoff & Ward, 2011; Sharma et al., 1997). Crises especially come with unexpected challenges, typically requiring fast and decisive strategic decision-making (Ritchie, 2004), since a crisis is a situation that threatens business continuance (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). Although there is limited research on how family firms manage crises (for some exceptions, see Cater & Beal, 2014; Cater & Schwab, 2008; Faghfouri et al., 2015; Kraus et al., 2020), especially the COVID19 pandemic led to new streams of research on how family businesses had to implement crisis management measures and adjust their strategy accordingly. Existing research mostly adopts a macro level perspective on the response to the COVID19 pandemic, focusing on digitalization (Guo et al., 2020; Soluk et al., 2021), resources (Calabrò et al., 2021; Leppäaho & Ritala, 2022) and internal and external factors influencing resilience on the organizational level (Schwaiger et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). An exploratory approach on the strategic response to the crisis by Kraus et al. (2020) revealed that family firms often apply measures that can be assigned to five overarching topics: (1) safeguarding liquidity, (2) safeguarding operations, (3) safeguarding communication, (4) business models, and (5) cultural changes to emerge from a crisis stronger in the long run (Kraus et al., 2020).

Building on that, we understand crisis management as the strategic response to disruptive change, namely to a situation that threatens the survival of the business (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). Hereby, especially in times of crisis, family businesses might be forced to carry out strategic transformation in the form of innovation (Leppäaho & Ritala, 2022), digital transformation, and strategic change (Guo et al., 2020; Soluk et al., 2021). According to Rumelt (1995, p. 10), transformation is “the process of engendering a fundamental change in an organization leading to a dramatic improvement in performance [… which] may involve strategic redirection”. His model distinguishes between recovery and renewal, defined as “the process of developing new skills and resources or of discovering new uses for extant skills and resources” (Rumelt, 1995). From this perspective, transformation suggests not just a return to a previously existing state but movement through and beyond stress or suffering into a new and more comprehensive personal and relational integration.

3. Research Method

Drawing on a positivist approach with the theoretical purpose of exploring how and why family businesses differ regarding their resilience and the implications for their crisis management, we applied a case study research approach (Leppäaho et al., 2016). A case study is an empirical inquiry that “… investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the ‘case’) in depth and within its real-world context …” (Yin, 2018, p. 15). This builds on the understanding that you need to consider contextual conditions to comprehend a real-world phenomenon and that “… context and phenomenon are not always sharply distinguishable…” (Yin, 2018, p. 15).

Given the limited insights we have regarding the resilience of family businesses, conducting a case study allowed us to generate a new or extended conceptual understanding (Hall & Nordqvist, 2008), thereby elaborating theory from a rich set of qualitative data (Patton, 2002). We conducted a multiple-case approach whose cross-case analysis “… forces investigators to look beyond initial impressions and see evidence through multiple lenses …” (Eisenhardt, 1989, p. 533). Therefore, similarities and differences can be found (Eisenhardt, 1989) and it is important to describe the cases in detail and in depth to address questions of generalizability (Patton & Appelbaum, 2003).

3.1. Case selection and research setting

As for every form of research approach, a case study requires a distinct sampling strategy to decide who to interview and which settings to examine (Punch, 2014). As we were interested in analyzing how owner-managers in family firms (re-)act in the case of a major crisis, we focused on an extensive set of cases based on the same business ecosystem and the same industry sector. This enabled us to identify within-group differences, as we executed a theoretical replication to find contrasting results but for expectable reasons (Yin, 2014).

We chose 141 small- and medium-sized regional fashion retailers located in Germany that are all part of the same business ecosystem but vary in their corporate structures. Looking for extreme cases (Flyvbjerg, 2006), we chose this context because the retail sector was hit especially hard by the COVID19 pandemic, and their business model, and hence the fundament of their business, ceased to exist. This gave us the advantage of studying and comparing many owner-managed family businesses with foreseeable similarities (e.g., business models) as well as differences (e.g., size). Since the goal of our study is to explore differences in family businesses’ reactions to crises in terms of their resilience, these family businesses all belong to the same business ecosystem; thus, overall, we followed purposeful sampling logic (Palinkas et al., 2015; Patton, 2002). Additionally, all companies under study faced the same crisis - the COVID19 pandemic - with the same timeframe and starting point. This gave us the opportunity to compare the crisis response and resilience dimensions in a rather objective manner, as all companies were in the same situation and had to deal with the same circumstances. For a detailed description of the cases under study, see Appendix 1.

3.2 Data collection

While the pandemic also poses challenges for conducting research (Rahman et al., 2021), we were able to consider alternative data collection methods in advance. Therefore, we chose a combination of virtual interviews and on-site observations to overcome the ‘distance away from the research site’ (Howlett, 2022) and balance benefits and challenges of conducting remote qualitative research (Rahman et al., 2021).

Consequently, to gather rich data, we collected the following data on the 141 cases: (1) observations of the businesses under study, (2) archival data about the business and its environment, (3) website data, and (4) two waves of semi-structured interviews with the owner-managers of the family businesses, first in focus groups and second through telephone interviews. The data were collected as part of a larger research project on family businesses with owner-managers. For a more detailed description of the data sources, see Table 1.

|

Table 1. Types of data and use in analysis |

||

|

Data type |

Description |

Use in analysis |

|

Observations |

The first author observed meetings (board meetings, senior management team meetings, strategic planning meetings, strategy ‘away-days’), took part in casual conversations and did site visits. |

|

|

Website analysis |

Over a period of 15 month (March 2020 to July 2021) a group of trained students analyzed the online activities of the family firms under study. |

|

|

Focus group interviews |

Eleven semi structured focus group interviews varying from two to six participants (90 minutes each), using Microsoft Teams, recorded (more than 44 hours of video material) and transcribed verbatim (400 pages). |

|

|

Telephone interviews |

Ten semi structured telephone interviews with a length of 60 minutes in total, specifically asking follow up questions. |

|

Conducting a rich dataset helped us to triangulate our data and mitigate possible biases (e.g., social desirability bias) from the interviews. Furthermore, a vast dataset was needed, as we wanted to understand whether all family businesses reacted the same way to the crisis. Conducting interviews in a focus group setting enabled us to replicate the business ecosystem logic in our research setting and understand interrelations between the actors as these group discussions build on inherent dynamics and help to explore the issues in context, depth and detail.

3.4. Data analysis

Data analysis drew upon established approaches for qualitative studies (Patton, 2002). In following an inductive approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), we moved back and forth between the data and an emerging theoretical understanding of crisis response and resilience in the case setting. We focused on how individuals managing and controlling a business responded to the COVID19 pandemic as a form of massive crisis, why they proceeded as they did, and what the consequences were. Our analysis progressed in four steps as we developed and refined our findings.

Step 1 – Individual case analysis

First, we analyzed each of the cases separately to gain an understanding of their characteristics. Detailed descriptions were condensed with the help of all data sources. This resulted in the identification of digital transformation as a central strategy of crisis response in the family businesses under study. Following Hanelt et al. (2020, p. 2), we define digital transformation as a specific type of strategic transformation in which “organizational change [is] triggered and shaped by the widespread diffusion of digital technology.” This is supported by Bharadwaj et al. (2013, p. 471), who stated that “digital technologies […] are fundamentally transforming business strategies, business processes, firm capabilities, products and services, and key interfirm relationships in extended business networks.” Proceeding with our analysis, we focused on all data related to digital transformation as a strategic response to the crisis to identify similarities and differences across the cases under study.

Step 2 – Analysis of pace and quality of crisis response

In the second step, using Atlas.ti software, we engaged in a cross-case analysis. Drawing upon grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Gioia et al., 2013) allowed us to refine how the family business owner-managers and their family businesses responded to the crises and captured their digital transformation as a central strategy. This second step resulted in an overview of the different modes of crisis management of the family businesses under study regarding digital transformation. Building on the existing literature, we found three modes and identified them as react, adapt, and consolidate. Analyzing the cases with regard to these crisis modes, we discovered that the family businesses under study varied largely with regard to the pace and quality of their strategic responses to the crisis. Since the COVID19 pandemic had a single starting point, we were able to retrace the pace of the family businesses’ individual crisis responses by analyzing which crisis mode was fulfilled at a given time.

To measure the quality of the strategic response, we followed Guo et al. (2020) and combined the general countermeasures, the overall digitalization degree (adoption of digital technologies) of family business, the evaluation of the strategy from a customer perspective, and the overall strategic fit.

Step 3 – Identification of four types of owner-managers

Third, to understand the reasons behind the differences in pace and quality in crisis response, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis using the constant comparative method (Silverman, 2006). By rereading the emergent types and independently coding the data, we assessed the reliability and uncovered the meaning of the data and the emerging categories. Taking short notes facilitated iteratively moving back and forth between the data, the emerging categories, and the literature. Building on that, we focused on the different levels of resilience of the family businesses (i.e., personal, business, and relational resilience). As the analysis progressed, we refined our categories, finally identifying similarities and differences in the interplay of family business resilience and crisis response in the cases under study.

Thus, we identified four different types of owner-managers within their businesses based on their pace and quality of crisis response, explained by differences in their resilience configuration. Therefore, in this step, we organized the businesses with regard to their pace and quality in crisis response (i.e., low vs. high), related to different resilience dimensions (e.g., personal resilience), and corresponding codes (e.g., mindset or personal knowledge base).

Overall, inductively analyzing the case data was beneficial in two different ways. First, grounding the codes and categories in the data helped us refine the existing research without losing its connection to it. Second, rather than forcing data into predetermined categories, we inductively moved back and forth between data and allowed categories to emerge, which, along with the theory, generated a better understanding of the phenomena under investigation and, thus, more insightful findings.

4. Findings

Our study was designed to explore how and why family businesses differ in their resilience and how it influences their crisis response. Analyzing our extensive qualitative data revealed that all firms in the ecosystem were affected equally by the crisis due to the lockdowns and the forced closing of their business. All interviewees perceived the COVID19 pandemic as a direct and insurmountable threat to their family business, fearing the loss of the family’s wealth.

“When COVID19 appeared, the first thing to do was to go into crisis mode. There was naturally the worry of losing the capital that had been built up over the years from generation to generation. For a short time, I thought, damn it, I can see how the family legacy is being destroyed.” (C19)

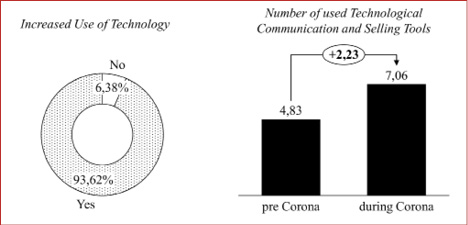

However, it is also a chance to strategically transform, that is, to adapt and innovate. Our data showed that the majority of family firms under study increased their usage of customer-focused communication technologies permanently during the COVID19 pandemic, implying a digital transformation.

Figure 1. Increased use of technology

More specifically, we found that almost all of the businesses under study went through three modes of crisis management—react, adapt, and consolidate—confirming that there was no difference in the issues family businesses have to address in times of crisis but only in how they responded. Table 1 provides more detail of the actions and crisis mode the family businesses took in response to the crisis, as well as which of Kraus et al.’s (2020) overarching topics were identified in their responses.

Building on that, our data showed that all three dimensions of family business resilience (personal, business, and relational resilience) were central to the crisis response. Comparing crisis response and resilience across the cases, we identified several resilience dimensions that are central to family business resilience. These will be described in more detail in the following sections.

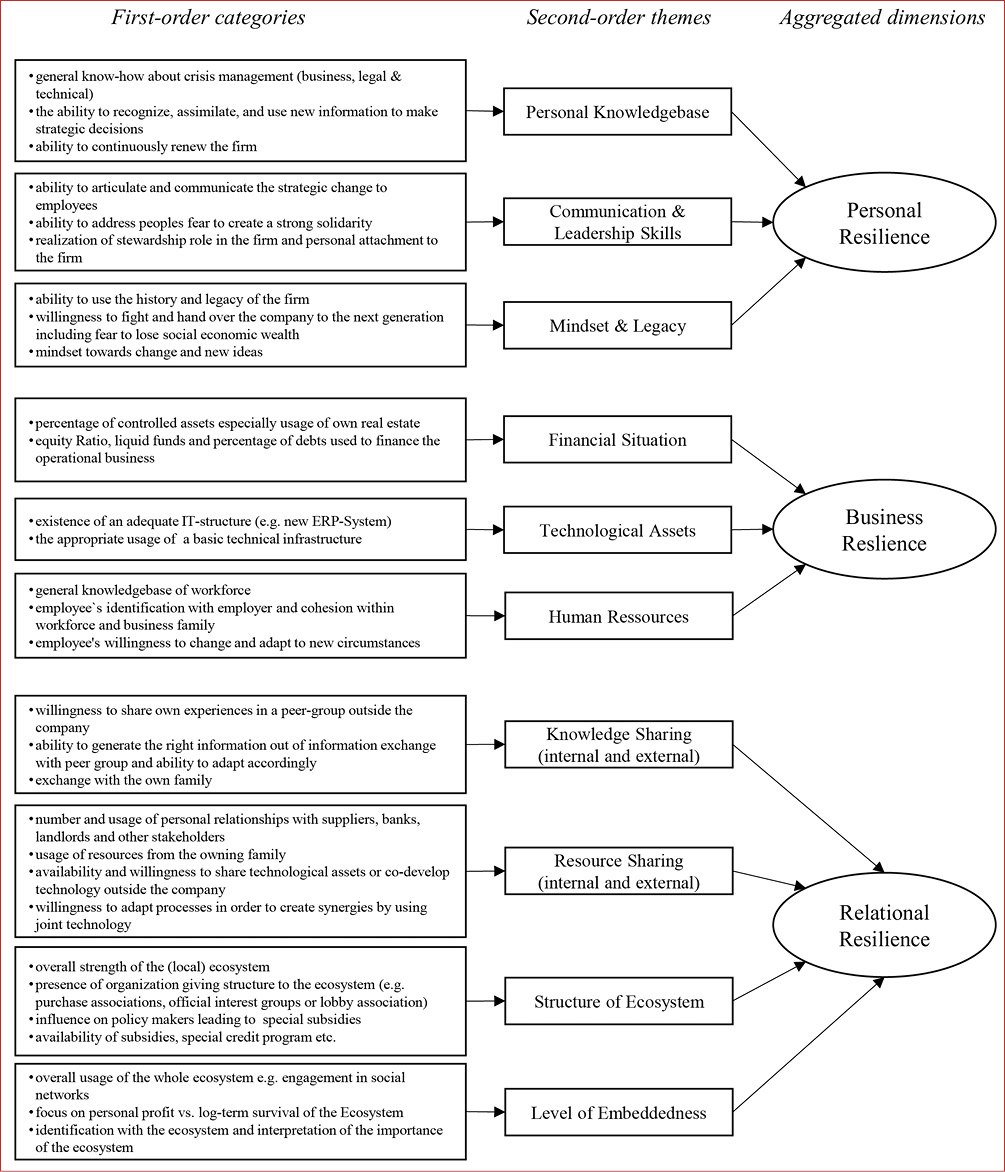

4.1. Three dimensions of family business resilience

Analyzing the crisis response revealed differences in family businesses’ ability to avoid, absorb, respond to, and recover from situations that could threaten their existence. We found these dynamic processes of resilience, involving the ability to learn and positively adapt, at different levels of the businesses under study (i.e., individual, business, and relational), with different factors facilitating these dimensions. An overview of these findings is depicted in Figure 2. Thereby we clearly identified resilience in family businesses as a multidimensional construct where all dimensions form the businesses’ overall ability to counteract a crisis.

|

Table 2. Overview of crisis responses by family businesses during COVID19 |

|||

|

Crisis mode |

Overarching topic |

Measures |

Representative quote |

|

React |

Safeguarding |

Special credit programs |

“I think short-time work was the first thing everyone introduced, and I’m still working with reduced opening hours to keep personnel costs low. I have also discussed rents with my landlords. Fortunately, it wasn’t really a deciding factor since I’m in my own property for the large part of my business. In addition, I have provided myself with liquidity through various governmental credit programs. I don’t know yet whether I will draw down all the loans, but it makes me feel safe.” (C139) |

|

Direct subsidies |

|||

|

Short-time work |

|||

|

Cutting rent |

|||

|

Safeguarding |

Keeping good personnel |

“But we have to manage our company in such a way that it’s powerful enough to feed the family. There is no goal of generating 5% returns, for example. If that’s the case, to take on an investor’s perspective, we shouldn’t have made the decision to top up our employees’ salaries while they were on short-time work. If we keep the people in our company and keep them happy, we don’t have to look for new employees after the crisis and re-train them. It’s about long-term goals.” (C14) |

|

|

Reducing working capital |

“And when the lockdown began, it was the start of the most important weeks of the year for us, and the warehouses were full. And it completely frightened us. We instantly hopped onto the well-known marketplaces very quickly. Just to sell products, reduce inventories, and somehow flush liquidity into the company.” (C10) |

||

|

Safeguarding |

Staying in touch with customers |

“We printed out a list of our most loyal customers and our stuff called them and asked if we can deliver surprise packages to their homes. And of course, we also introduced WhatsApp group customers.” (C24) |

|

|

Addressing employees’ fears |

“But with the pandemic, communication has become the most important task just to give employees solidity and confidence. That has changed so much for us now.” (C92) |

||

|

New communication tools |

“We have introduced Threema. It has been extremely helpful for us because we were always in touch with everyone. We also made no distinction between hierarchical levels.“ (C119) |

||

|

Direct communication |

|||

|

Crisis mode |

Overarching topic |

Measures |

Representative quote |

|

Adapt |

Business |

New business segments |

“Even long before Corona, we had been speculating about to do an online shop. And we didn’t really do it until the lockdown came. We told ourselves: If not now, then we will never do it. And we went all the way, and we haven’t regretted it since. Corona was just a driver for innovation“ (C19) |

|

Cultural changes |

Sense of solidarity |

“The employees came to me: “Boss, we’ve done other things together and we’ll get through this. We stand by you, and if I have to give up money so that we can get through the crisis, that’s okay.” (C135) |

|

|

Identification with new business segments |

“We’ve had all these communication tools for a while. But some of our employees are older. Now even the last ones bought a smartphone to get all the information, and those were the ones who were totally excited when the first orders came in via the online store.” (C76) |

||

|

More responsibilities |

“The young people worked their way to the forefront, which was positive. The apprentices were also able to work on their own, especially during the lockdown phase, when we had a lot of short-time work for the regular employees. Every single person had to work independently, but the new technologies also made it possible to break down hierarchies.” (C26) |

||

|

Consolidate |

Business |

Review of measures |

“During Corona there was of course a lot of trial and error and mainly short-term goals. Now, we are reviewing all the measures and trying to aim for long-term transformation. For instance, we are now using our interfaces in online marketplaces with a different strategy. “(C83) |

Personal resilience

All the owner-managers under study confirmed that the pandemic strongly influenced their own role in the company and that their personal involvement had changed. They had to focus more on operative subjects, including legal topics such as short-time work or other subsidies like special funding program for the introduction of new technologies. Additionally, strategic decisions, for example, about implementing new technologies and investing in digitalization measures, were made by the owners themselves in family firms. Thus, personal resilience was a key factor in family firms. This included the personal knowledge base and capabilities of the owner-managers, as they had to adapt to the crisis. Their personal know-how about crisis measures mattered, but most of the owners emphasized their own ability to recognize and assimilate new information to make strategic decisions.

“What kept you busy is that you had to leave your role as an entrepreneur. I had to find my way back into areas in which I had no previous experience. have never dealt with all this: short-time work, subsidies, digitalization, and so on… but I had to gather information to be able to make the right decision.” (C96)

Other personal resilience identified included leadership and communication skills, as the family business owners were also the face of the company toward the businesses’ employees and customers. Thus, fulfilling the role of steward and strengthening personal attachment increased resilience. In particular, the ability to articulate and communicate strategic change and to share the contingency plan was important. These communication skills were highly relevant to creating strong solidarity and identification with the company, as employees feared uncertainty.

“As the head of the company, you tended to back off a bit in the period before. You developed the strategy, you are in the background, and you have the vision. But because of the pandemic, this communication has become extremely important, just to give the employees firmness and confidence.” (C92)

Figure 2. Dimensions of family business resilience

Further, the mindset and the use of the firm’s legacy seemed to be pivotal. Although almost all the owner-managers perceived the pandemic as a crisis, there were differences in the extent to which it was also seen as an opportunity. Most of the companies under study had to adjust their business models or product ranges several times in their history; however, not all companies made use of the past—that is, used their legacy to form a mindset that was open to change.

“So, if we hadn’t changed, we wouldn’t be in the 6th generation now. We started as a small mom-and-pop store and have grown through a bed department store that my father ran. And now, in my generation, we have turned it into a fashion store and are going down the path of digitalization. So, it’s about changing all along. But it is also about succession. To hand over this legacy.” (C92)

Business resilience

At the business level, three second-order themes that formed business resilience were identified, as shown in Figure 2. Many participants highlighted the businesses’ financial situation as a success factor in the crisis. The family firms focused on long-term goals, allowing them to operate with a high equity ratio and often using their own real estate for the operational business.

“50% of the store space we use, and the lion’s share in terms of square meters, belongs to ourselves. That let me sleep more calmly in the pandemic because I knew that I don’t have to pay rent to myself.” (C83)

“As a family business, I fortunately don’t have to report to an investor who wants dividends every year. We keep the money in the company. I’ve never had to take out short-term loans to finance goods, and even now in the pandemic, I’ve only applied for loans as a security measure, but in the end, I was able to pay everything out of equity.” (C73)

Another aspect of business resilience identified was human resources—that is, the abilities of employees. In particular, flexibility, and adaptability were mentioned. This seems to be especially the case for smaller family businesses because the areas of responsibility of both the management and the employees are very diverse and less specialized than in large companies.

“During the crisis, I also discovered new skills in some employees. All of a sudden, our IT colleague was obsessed with the possibilities of social media marketing and provided a lot of new impulses.” (C135)

Furthermore, existing technology in general was understood as a sub-factor of business resilience. This included not only the sheer existence of technology but also whether it was appropriately used.

“Fortunately, we had already invested in IT and kept our ERP at an adequate level. This made it easier for us to implement further interfaces to our own online shops and online market places.” (C10)

Relational resilience

Both on the personal and on the business level, participants repeatedly emphasized how important the interactions between the various players were in getting through the crisis. Thus, managing and making use of relationships seemed to be critical within, but especially beyond, the organization. Our data showed two ways in which relationships were used to strengthen resilience (knowledge sharing and resource sharing) and the importance of the overall ecosystem (structure of ecosystem and level of embeddedness). The data showed that close exchange with the owner’s family was used to make the right decisions. In this way, questions could be discussed from different perspectives, and the skills of each family member could be used more efficiently.

“At the moment, we are four family members working in the company. My sister and my parents. All of our decisions are discussed internally first.” (C101)

This aspect seems to be more pronounced in family businesses, where the owner-managers are embedded in a network of strong social ties with their own family as well as friends, personal business contacts, and employees. Our analysis of relational resilience revealed that owner-managers used these social ties mainly in two ways. Knowledge sharing refers to their use of their own networks to learn from the experience other firms had made, thus gaining personal knowledge.

“Online sales were low until I talked to another retailer. He then told me three times here, three times there and behold, sales skyrocketed.” (C10)

Especially in terms of strategic decisions, the network was a resource, and thus, the ability to generate the right information out of information exchange with peer groups and the ability to adapt accordingly was a resilience factor.

“And I’ve always been like that with an idea, rather well stolen than badly invented myself. And that basically was enhanced by the pandemic because I was lucky enough to have stumbled into this exchange panel relatively early, with the first Lockdown. This meant that I was always in a close exchange with many other retailers from the very beginning and was naturally able to pick up on ideas that have proven themselves with others [...] and develop the strategy accordingly. […]” (C17)

Resource sharing additionally included the joint use of IT systems and accordingly the availability and willingness to share technological assets or co-develop technology but also the willingness to adapt processes to create synergies by using joint technology.

“Without the use of central IT structures, which were made available for us through a partner network, we would never have gone live on all the marketplaces within such a few days, and our web shop project would still not be completed today. We don’t even need to talk about the costs at this point. They would also be many times higher.” (C133)

Further, there were personal relationships between the owner’s family, suppliers, and other stakeholders that could be used during the crisis to reduce costs in the short term, which can be defined as personal favors.

“...with the landlord of one of our stores, I am in the local choir. This also helped to negotiate the rent.” (C83)

This knowledge- and resource-sharing mechanism, including personal favors, can be further divided into whether the owners consumed or provided only for themselves. Our data showed that the resilience of the family businesses under study also depended heavily on the structure of the business ecosystem in which they were embedded. The ecosystem can be viewed and expanded at different levels. On the one hand, there was local biotopes, which was especially important for local family businesses in the retail sector.

“What happens to my downtown biotope? What do I need from the outside for me to exist or for the business to exist? And to what extent is that within my control? […] I prefer to act in such a way that I not only strengthen my own company, but also make sure that the surrounding area is doing well...” (C87)

On the other hand, there was the business side of the ecosystem, which included suppliers, customers, competitors, and the same types of businesses in other regional settings. A strong ecosystem also fostered the resilience of the family firm.

“This construct of medium-sized, owner-managed retailers only works as long as all the companies involved act in partnership. Corona demonstrated this to us. We retailers need brands in our stores. We are too small to do everything ourselves. We don’t need to gloat when fashion brand X or retailer Y goes bankrupt. That harms us just as much.” (C95)

However, these ecosystems must also be managed. Thus, for instance, purchase associations are an integral part of giving structure to such an ecosystem and guidance to the players involved but also negotiating with policymakers about the special needs leading to, for example, subsidies. In particular, the availability of these government grants made it easier for family firms to adapt as they were for instance designed to help companies to implement new technologies.

“Even though everyone is always ranting about the purchase associations. In the crisis, I was glad to be a member of it and to be able to rely on its advice and its good network to our suppliers, other retailers, and policy makers. […] The availability of the subsidies [like the digitalization bonus] provided by the government made it easier for us to get through everything.” (C133)

This shows that the survival of the entire ecosystem is sometimes more important in a crisis than short-term profit. Hence, it is particularly noteworthy at this point that some participants in the ecosystem examined deliberately put their own interests aside to ensure the survival of the entire system.

“We also followed the associations’ recommendation during the crisis and did not disagree when the payment terms were changed centrally for several months, and we gave up a 4% discount as a result. We would still have had enough liquidity, but it was more important for me to work in solidarity with the other retailers so that we all came out stronger.” (C73)

Figure 3. Overview of findings

Figure 4. Four types of owner-managers and their family businesses

Interestingly, combining these findings, although all businesses under study exhibited resilience, we found large differences regarding the pace and quality of their strategic reaction (transformation) to the crisis. The resilience dimensions of the owner-managers and their family businesses under study showed an interplay leading to different process configurations in their crisis response modes. Thus, only when they successfully processed the adapt and consolidate modes was a strategic transformation achieved.

4.2. Four types of owner-managers and their family businesses

Based on the crisis response of the businesses, we focused our analysis on the general countermeasures to safeguard the business and digitalization as one form of strategic response to the crisis. These responses can be assigned to the three crisis modes. Overall, the reaction mode is about implementing short-term countermeasures to secure the company and the family assets, whereas the adaption and consolidation phase is about making strategic decisions to engage in strategic change and renew the company by developing new skills or implementing new business segments and finally reviewing those measures to reinvent the company and recover from the crisis (for a detailed depiction, see Table 2).

We were able to identify four types of owner-managers and their family businesses, which largely vary regarding the quality and pace of their crisis response. For a depiction of the four types, see Figure 4. Overall, we found that the rationale behind the differences lies within the resilience dimensions leading to four typical configurations for owner-managers and their business’. We found a strong connection between the owners’ business resilience, especially in terms of their financial situation, and the pace of the crisis response. Further, our findings suggest a link between relational resilience and the quality of the crisis response.

Type 1: The family business survivor

This type of family business owner-manager never really leaves the reaction mode and primarily focuses on countermeasures to overcome the crisis instead of engaging in many measures to adapt to the new circumstances and transform the business. Owner-managers of this type especially focus on countermeasures to safeguard liquidity by using special subsidies, and they are focused on short-term goals rather than on long-term strategies. Therefore, the quality of their crisis response is also rather low, as their strategic transformation is almost nonexistent. In terms of short-term countermeasures, they engage in a few but do not particularly safeguard communication.

In terms of family business survivors’ personal resilience, one can highlight that they have some basic knowledge about crisis management but especially lack the ability to assimilate new information to make strategic decisions to renew the firm. This also continues in that they fail to inspire their workforce or being a strong role model. Additionally, they fear risk and are not open-minded to change, focusing on preserving the company’s tradition and current state.

The company’s financial situation is rather critical, as it has to work with a low equity ratio, regularly requiring short-term debt to finance the normal operational business even during stable times. Often, technological assets are rather outdated, and its digital transformation not only includes integrating new technologies but also replacing existing IT infrastructure. Its workforce is usually overaged, has been in the company during their whole work life, and lacks the skillset needed to engage in a quick and fitting transformation to the new given circumstances.

In terms of relational resilience, the owner-managers do not often use their personal network to gain information and only consume information rather than providing input themselves. They are also focused on their personal family rather than on their business network. This is also true when it comes to interactions with employees. Overall, they are not really embedded in their ecosystems, as they have low engagement and no real identification with the other players being focused on themselves. Thus, these owner-managers and their family businesses never really outlive the crisis mode and do not engage in strategic transformation.

Type 2: The family business egoist

This type engages in many measures to tackle all three crisis modes, as they are already consolidating their means and reinventing themselves. However, the quality of the family business egoists’ crisis response is also rather low, as their transformational output is perceived as unfit from a customer perspective. They engage in all countermeasures but do not have to execute these in a perfect manner, as their financial situation gives them the freedom to keep the business running, even without the use of, for example, all the special credit programs available. By that, they give away potential sources of revenue. The family firm has a high equity ratio and often uses the family’s real estate, and the IT structure has been renewed frequently. The owner-managers use this financial freedom to engage in transformational measures by including new business segments and digital communication tools. However, although the overall extent of digitalization is high, the output is still low in terms of strategic fit and execution. This is partially because their employees are not included in strategic decisions, especially as the owner-managers do not really articulate and communicate the strategic change addressing the cultural changes during the adaption phase.

Overall, they are not really embedded in the ecosystem, as they are rather inward-looking seeking their own benefits. Their focus is on the personal and business dimensions of resilience. They already have a broad knowledge base that was partly generated by using knowledge-sharing measures in the past but only in a consuming manner. They can assimilate information to make the right decision and are open to change but lack execution. As addressed before, their financial situation is good, their technological assets are up-to-date, and they can invest in the skillsets of their personnel. However, cohesion and identification within the workforce are especially low.

Concerning the relationship level, overall involvement in the ecosystem is focused on the owner level rather than on the employees. Overall, there is no real identification with the ecosystem. These owner-managers aim to exploit it because they are focused on consuming possibilities out of the ecosystem. This leads to using shared resources/technologies when it seems appropriate for them and their business but only in a consuming manner.

Type 3: The family business meticulous

Owner-managers belonging to the family business meticulous type focus on adapting to the crisis but their ongoing transformation is of high quality. Their financial situation is especially limited, so they must exploit every possibility to gain synergies. Hence, within the countermeasures, they are very meticulous in using every governmental program available to safeguard their company’s liquidity while implementing measures to reduce the working capital. Although they can address their employees’ fear and articulate the upcoming strategies, they have a deficit concerning their own knowledge, but they overcome this by heavily relying on knowledge-sharing mechanisms on all levels of their organization and are also contributing to the ecosystem themselves. However, they are often hesitant to implement measures in a timely manner because of their firm’s financial status, and thus, they do not use all the resources available through their network to adapt in the short run. However, the owner-managers need to use these shared resources to create synergies, as the companies’ technological assets are on a basic level and need to be renewed. This is also the reason why their identification with the ecosystem is high, and they are willing to share their experience so that other owner-managers can learn from them.

Their employees are eager to compensate for the financial situation, as they have a strong identification with the business family, but their general knowledge base is rather outdated.

The owner-managers often rely on the firm’s legacy and their willingness to hand over the company to the next generation when implementing strategic measures and engage in lengthy discussions with their own family to exploit the family’s knowledgebase. Overall, they highly use knowledge sharing and provide their own insight into the ecosystem but are comparably slow in leaving the crisis modes.

Type 4: The family business activist

The family business activist tackles all dimensions of crisis response and focuses on reinventing and continuing business activities. These owner-managers’ transformations are successful, and their transformational efforts are of high quality. They have basic knowledge about crisis management and strategic transformation but are constantly learning, as they can assimilate and use new information to make strategic decisions, which is in line with their ability to constantly renew the firm. They use their own network to gain such information, especially outside their business family, and rely on knowledge sharing at all levels within their organization.

Although their family business is financially stable and can afford to invest from its cashflow, the owner-managers are highly active within the ecosystem, and their business uses shared resources to further strengthen the company’s position. They can address the cultural changes that come with a strategic transformation to create strong solidarity and identification among their personnel. Especially noteworthy is the willingness to change and adapt to employees. Overall, they are highly embedded in their ecosystem and focus on its long-term survival, as the see the importance of the overall construct.

5. Discussion, Conclusion, Future Research, and Limitations

By conducting a multiple case study and analyzing a rich set of data, we offer several insights into family business resilience and crisis response, thereby adding to both the field of family business research and the existing stream of research on resilience.

First, our study contributes to the research on resilience by extending the knowledge on different dimensions of resilience that can be found at different levels in a business. In doing so, we especially highlight the multidimensionality of the resilience concept, helping to refine existing conceptualizations and diverging research (Ventura et al., 2020).

Besides the conceptual contribution, our qualitative exploratory approach allowed us to emphasize the importance of the relational aspect of resilience, which has been neglected in research so far. Although there are research streams exploring the concept of relational resilience, they focus primarily on internal relationships, especially within the business family (Calabrò et al., 2021) while neglecting external interlinkages as emphasized by social network and business ecosystem theory. Hence, our research adds especially to these streams by showing that relational resilience exists not only within the company but also within the whole family business ecosystem and thus includes internal and external factors (Schwaiger et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). Following these external links, future research should include the perspective of community as a strategic resource, as introduced by Gibson, Gibson, and Webster (2021), to further investigate the special role of communities in which family businesses are embedded.

While most research focuses on the business family, showing the family business’s ability to leverage their family’s social capital and patient financial capital to gain resilience (Calabrò et al., 2021), we find that the owner-managers’ personal ties with industry experts and other owner-managers make a significant difference. This adds to current research streams focusing on the owner-managers’ ability to look for alternatives and deal with complex situations (Renko et al., 2021; Santoro et al., 2021) by implying that their personal relationships beyond the business help them to identify those alternatives and develop the skillset to deal with a crisis. We thereby emphasize that personal networks are not only an antecedent of resilience (Herbane, 2019) but also an elementary success factor.

The positive link between the owner-managers’ resilience and the organization from a psychological resilience perspective has been shown (Hadjielias et al., 2021). However, our research paints a bigger picture, identifying that the owner-managers’ personal resilience (e.g., their mindset and leadership skills) is only one integral part of the multidimension construct of family business resilience. Nevertheless, future research should especially analyze the interplay between the owner-managers and their workforce in times of crisis, as we found human resources, and especially the workforce’s identification with the company, to be a central factor for a family businesses’ resilience. Therefore, cultural changes evolving through crisis response (Kraus et al., 2020) must be addressed. This shows the close interconnectedness of personal, relational, and business resilience, which all adds up to effective coordination and knowledge integration (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005; Williams et al., 2017). These adjustments, in turn, are positively influenced by relational coordination in the form of effective communication and integration across roles and functions (Anwar et al., 2021). Altogether, they form the three key domains of resilience—communication, problem solving, and adaptability (Burnard & Bhamra, 2011).

Overall, we not only show that strong relationships lead to resilience (Mzid et al., 2019), but we also identify two central mechanisms to exploit relationships to gain resilience: knowledge- and resource-sharing. Although knowledge sharing and collaborative relationships have been investigated as a way to support strategic decision making (Wulf & Butel, 2017), we show that they are most prominent in family businesses with owner-managers and especially helpful in times of crisis. We further identify that family businesses collaborate in terms of resource sharing in the form of co-developing technologies or using technologies that have been provided through their partner network. We also show that it is not only family firms’ embeddedness in the regional ecosystem that is beneficial for both the ecosystem and the organization (Bichler et al., 2022); the structure of the ecosystem itself influences the resilience of family firms. Building on ecosystem theory, these results should be further discussed to combine ecosystem and social network theory with family business research and to further analyze these central mechanisms, especially how they arise and need to be managed.

Additionally, our research reveals that the different resilience dimensions have a direct influence on the pace and quality of the strategic crisis response and the measures taken. We find a strong connection between the owners’ business resilience, especially in terms of their financial situation, and the pace of the crisis response. Further, our data suggest a link between relational resilience and the quality of the crisis response. Therefore, we extend the research on the interplay of crisis management and resilience in family-run businesses by combining the identified crisis modes and resilience dimensions. This interplay can be used to further analyze the resilience of family firms during a crisis.

Second, our study adds to the current research on crisis management in family businesses by elucidating the three different modes of crisis response that emerged from our data analysis: react, adapt, and consolidate (Kraus et al., 2020; Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005; Sharma & Salvato, 2015). We show that companies can only emerge sustainably stronger from the crisis if they go through all three crisis modes and transform and reinvent themselves accordingly. Further, we can show that most of the businesses under study adapt the same three crisis modes, while a few remain stuck, overly focusing on tackling only certain parts of the crisis-related challenges. Thereby we also shed light on the relationship between resilience and strategy, extending existing research on family businesses’ response to the COVID19 pandemic (e.g. Calabrò et al., 2021; Schwaiger et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). Our research additionally adds value to current research streams on digital transformation in family businesses by highlighting the special role of the family and the owner-manager when adapting new technologies (Ghobakhloo & Tang, 2013), adding up to current research showing that, for example, paternalism is a barrier to transformation (Soluk & Kammerlander, 2021). Accordingly, future research should also focus on digital transformation in family businesses in general, given our findings of the increased use of technology and increased digitalization efforts as a significant countermeasure. Such investigations were used to provide insight into crisis management itself.

Third, our research supports the current research streams regarding the special role of owner-managers, as they have ultimate control over the business (Schulze & Zellweger, 2021) and are thus the primary strategy makers in family businesses. Therefore, we offer implications for how owner-managers are influenced by their personal network in their strategizing, especially since knowledge sharing is used to support strategic decision making (Wulf & Butel, 2017). This should be further investigated, especially within the paradoxical tension between the family’s legacy and tradition and the (crisis-induced) need to innovate (Erdogan et al., 2020) and whether relational ties within or without the family are more beneficial. Barriers to change in family business (Lorenzo-Gómez, 2020) have to be considered because change and renewal are central to allow the family to hand down the company to the next generation. In this context, the owner-manager’s identity might be relevant, as “founders’ identity … systematically shape key decisions in the creation of new firms” (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011), and research has shown that there is a close interplay between identity and strategy on the organizational level (Bövers & Hoon, 2021). Our typology of different owner-managers in family businesses is in line with the research on classification systems of family business research as it supports the heterogeneity of the family business concept (Hernández-Linares et al., 2017).

The study is not without limitations. First, we analyzed one specific (regional) ecosystem, which might lead to less generalizable results for family firms within other ecosystems. In particular, knowledge- and resource-sharing mechanisms might not be as applicable if the ecosystem under study is not as homogenous as in our case. Additionally, our findings emphasize that the general structure of the ecosystem is a resilience factor. However, our data did not show any variation, as only one ecosystem was the subject under study. To overcome this limitation, one option for future research is to validate our results in a quantitative study while including other ecosystems.

Second, although we triangulated our data and used multiple data sources, our findings are, to a certain extent, focused on data provided by family business owner-managers, which are often subjective and might lead to one-sided conclusions, especially when talking about the role of the employees. In particular, the results can be biased if there is only one informant (Chrisman et al., 2007). Following Holt, Madison, and Kellermanns (2017), a dispersion model could be used in future research to gain more insight by not only relying on the assessments through a single key informant.

Third, we focused on a specific snapshot in time (COVID19 pandemic), and thus, the results may vary for other crises, although COVID19 gave us the chance to study such a large quantity of owner-managed family businesses facing the same crisis to identify variance within the crisis response.

In summary, our study enhances knowledge about resilience as a multidimensional concept and the special role of relational resilience. We are able to show the mutual influence of the dimensions of resilience, as well as the consequences for short-term crisis reaction and strategic responses. Thereby, we extend the understanding of the strategic crisis response of family businesses and the prerequisites for strategic transformation. This complements the existing literature and emphasizes the need for further research on the relational aspects of resilience.

6. Practical Implications and Recommendations

This study offers several practical recommendations for family businesses, their owner-managers but also policy makers. First, it shows that family businesses always respond to crises through the same modes. Especially during the first crisis mode, staying solvent is essential, and hence practitioners should apply different strategies ensuring liquidity, such as ad-hoc cost-cutting measures but especially relying on the family capital and using government measures.

First, open communication with all stakeholders is essential to keep the business running and motivation high. Almost all interviewees stated that using new technologies to stay in touch with employees, customers, and suppliers was a central success factor during the crisis. Hence practitioners need to be aware of their different communication channels and interactions and should scan the market for new opportunities to keep the interaction between all stakeholders on a high level.

Second, our study reveals that the interaction between policy makers and family businesses is an integral part during a crisis. In times of crisis, policy makers should consider the special needs of family businesses and offer unbureaucratic support programs. Organizations who are forming structures, such as trade associations, play a crucial role in this process, acting as mediators and communicators between family businesses and the government. Therefore, this study recommends for policy makers to engage with trade associations, especially those representing family businesses, to stay informed about the businesses’ needs.

Third, this study shows that a high equity ratio and high cash rates are surviving factors for family business as they usual lack the ability to generate quick cash resource from the financial market e.g. via bank loans. Hence one can argue that to be prepared for upcoming crises, family businesses should focus on generating cash reserves. Additionally, family businesses need to be informed about current subsidy programs as during this particular crisis, these helped the businesses to stay solvent (e.g. short-time work) but also to adapt and implement new technologies (e.g. digitalization bonus).

Altogether, our study especially highlights that during the crisis, the family owner-managers are at the heart of all actions and are embedded in a broader ecosystem of the firm with several interlinkages within their social network. Their role changes from being the pure strategist to being the captain performing the operative ‘legwork.’ Nearly all the CEOs we interviewed stated that their involvement during the pandemic changed to more operative and communicational tasks. Hence, personal abilities are especially important in overcoming the crisis itself and transforming the company to the next level. However, smaller family firms especially lack the knowledge and/or resources needed. The family owner-managers turn to their personal network more frequently than during stable times, making the influence of the overall business ecosystem unmissable and a key driver of success and failure, especially during a crisis.

At such times, most family firms rely on interactions with other organizations interlinked to their business. Hence, the embeddedness of an organization within its ecosystem is an essential driver of resilience during a crisis. Especially interesting are the participants and the interlinkages within the ecosystem when analyzing the different ecosystem dimensions. Those dimensions include the horizontal (economic and socio-political environments) level, involving stakeholders such as suppliers, banks, and customers, as well as the vertical (industry regimes and family systems) level (for a deeper theoretical understanding, see Bichler et al., 2022). Our data additionally show that new ties, even between (former) competitors, are formed and used to overcome the crisis. Accordingly, the clear practical recommendation can be derived that owner-managers must see themselves as networkers. In doing so, they should focus primarily on the two identified mechanisms of resource and knowledge sharing to gain competitive advantages. Thereby our study shows that it is equally important to provide and consume resources and knowledge. These mechanisms can subsequently also be applied to intra-organizational relationships.

To sum up, this study adds value by providing family managers with practical implications for how to cope with a crisis and how to use the whole ecosystem to overcome the crisis. Our research shows that family business resilience includes more than one firm’s financial aspects, and that a strong social network can particularly help overcome a crisis by creating synergies due to knowledge- and resource-sharing mechanisms. Hence, our research explicitly provides insight to family owner-managers to manage and foster their relationships within, but especially without, the company to gain competitive advantages.

References

Ahuja, G. (2000). Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: a longitudinal study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(3), 425–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667105

Albers, S., Wohlgezogen, F., & Zajac, E. J. (2016). Strategic alliance structures. Journal of Management, 42(3), 582–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313488209

Amann, B., & Jaussaud, J. (2012). Family and non-family business resilience in an economic downturn. Asia Pacific Business Review, 18(2), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2010.537057

Amit, R., & Villalonga, B. (2014). Financial performance of family firms. In L. Melin, M. Nordqvist, & P. Sharma (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of family business (pp. 157–178). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Anggraeni, E., Hartigh, E. den, & Zegveld, M. (2007). Business ecosystem as a perspective for studying the relations between firms and their business networks. ECCON 2007 Annual Meeting, 1–28.

Antheaume, N., Robic, P., & Barbelivien, D. (2013). French family business and longevity: have they been conducting sustainable development policies before it became a fashion? Business History, 55(6), 942–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.744583

Anwar, A., Coviello, N., & Rouziou, M. (2021). Weathering a crisis: a multi-level analysis of resilience in young ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211046545

Aronoff, C. E., & Ward, J. L. (2011). Family business ownership: how to be an effective shareholder. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Arya, B., & Lin, Z. (2007). Understanding collaboration outcomes from an extended resource-based view perspective: the roles of organizational characteristics, partner attributes, and network structures. Journal of Management, 33(5), 697–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307305561

Astrachan, J. (2010). Strategy in family business: toward a multidimensional research agenda. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2010.02.001