European Journal of Family Business (2022) 12, 1-6

The Archetype of Hero in Family Businesses

Guillermo Salazar*

Managing Director of EXAUDI Family Business Consulting, USA

Commentary. Received: 2021-12-11

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10, M19

Family business, legacy, narrative, storytelling

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10, M19

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, legado, narrativa, narración

Abstract For family business advisors and consultants, the analysis of their client’s shared narrative helps them understand their business and family dynamics and the reality they have built together. Understanding the language of family mythology and the behavior of the narrative processes, can help positively to reinforce the purpose and meaning of their legacy and its transmission. In this article readers will learn how Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth of the Hero concept fits with the founder/entrepreneur myth in a family business, and how making it conscious can be used as a coherent tool that brings true meaning and inspiration to every family member in every generation.

El arquetipo del héroe en las empresas familiares

Resumen Para los asesores y consultores de empresas familiares, el análisis de la narrativa compartida de sus clientes les ayuda a comprender su dinámica empresarial y familiar y la realidad que han construido juntos. Comprender el lenguaje de la mitología familiar y el comportamiento de los procesos narrativos, puede ayudar positivamente a reforzar el propósito y significado de su legado y su transmisión. En este artículo, los lectores aprenderán cómo el concepto Monomyth of the Hero de Joseph Campbell encaja con el mito del fundador/empresario en una empresa familiar, y cómo hacerlo consciente puede usarse como una herramienta coherente que aporta verdadero significado e inspiración a cada miembro de la familia en cada generación.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12vi1.1463

Copyright 2022: Guillermo Salazar

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

Carl C. Jung (1875-1961)

Introduction

In more than two decades working as family business advisor, within the work process in the elaboration of any project with business families, I have found an unbreakable connection with the history of the venture that lies in the family’s collective conscious and gave rise to the current shared heritage and wealth, which is implicitly or explicitly manifested in the narrative of the members of the family group. This experience relays in the tool I want to present in this article: a practical instrument to address the entrepreneurial spirit to the next generations and, at some point, to understand the necessity of the retirement of the previous generation of a family business. To present these ideas, we will explore its origins through a theoretical framework, and then we will illustrate it with a real-life case. The readers of this article will discover a new tool, based in an ancient practice, to discover a family identity.

In the results of their studies, Kammerlander et al. (2015) demonstrated that shared stories can serve as an important means of transmitting and reinforcing the founder’s path from generation to generation and preserving it over the long term (“second-hand impression”). Interestingly, interviewees mentioned that the core of the stories shared among family members remained largely stable over time; however, each generation enriched the transmitted stories, thus being able to gently alter their content. As storytellers responsible for the shared legacy, each family can transform the myth and feed a group image of their past, of their known or lost origins in time, an “arranged”, “mythical” story, which highlights in the first place an ancestor who is singled out for particularly heroic behavior (Ruffiot, 1980). A focus on shared stories lends legitimacy to a broad spectrum of decisions, empowering family members of each generation with the motivation to commit to the long-term success of the company and overcome their own obstacles.

One of the core diagnostic exercises in the methodology that we have been using for the past two decades is the “Family Chronogram”. It is a procedure in which the live construction of the family diagram (Salazar, 2019) is integrated with a linear sequence of milestones, characters, places, values and experiences that configure some of the main elements of the mythology of the business family. Recreating the atmosphere of curiosity, expectation and fascination that have attracted man for millennia around the bonfire of the story, we collect the narration of the events that make up the story common, preferably with the presence of several generations of the same family, in which interrelated events are discovered and rediscovered, which unite and interweave in a dance of ancestral flames of fire that are revealed before their eyes, making conscious the unconscious of the relationship of the individual in his identity with the complex and shared narrative dynamics.

The analysis of the narrative helps us understand our client, the shared realities that have been built, those that are sustained and those that change, highlighting the relational processes and the context in which events unfold. However, the value of the true and extraordinary creative contribution of the story is for the family, especially if we have the ability as guides to the process of identifying the different elements that give structure and meaning to the story, ordering its characters, the sequence of events and the meaning of their messages. Understanding the language of family mythology and the behavior of narrative processes can help us to positively transform the purpose of the legacy and the meaning of its transmission to future generations.

Family businesses that foster a culture of intergenerational connections and a long-term vision include a strong set of family values and stories that are passed on to future generations (Denison et al., 2004). Throughout these years of my consulting practice in the transformation processes of business families seeking to professionalize their management processes, the common elements in their narrative when reconstructing their stories were increasingly evident. All of them, in some way or another, revolved around not so much on the character as in the myth of the founding entrepreneur and how he/she overcomes the adversities, grows and becomes the most important element of the narrative, from whom everything connects and depend to build the origin of a shared heritage and the identity of the family business. Regardless of the generation that is leading the business, whether this character is alive or not, or the current financial situation of the family wealth, we will listen again and again, the same story starring a main character in each case. And it is my perception, from my consulting experience, that we will listen how the business family builds their own story based on the hero archetype.

Anthropologist Joseph Campbell published in 1949 “The Hero of a Thousand Faces”, and since then has completely revolutionized the way we understand stories, combining psychological elements proposed by Carl Jung about symbols and archetypes, with the identification of coincidences in religious passages, legends, traditions, and tales from around the world. The author proposed the term monomyth as a universal mythological structure, applicable to all societies or groups of individuals that have built, over at least three generations, a collective identity (Campbell, 1949). A short time later Antonio J. Ferreira, a Palo Alto researcher who began to coin the term “family myth” as a unitary representation, corresponding to a homeostatic mechanism whose function is to maintain group cohesion, as a safety valve that prevents the family system from deteriorating and eventually destroying itself (Ruffiot, 1980). These are convictions installed in the unconscious of the individual, accepted a priori almost as something sacred, that none of the members can counteract or challenge, despite the evidence that may be presented, since it prevents the system from the threat of disintegration or chaos. During the 60s, Murray Bowen noted the specific patterns of behavior transmitted through innumerable generations, defining the psyche as the result of all the chronological conditioning factors that surround it. For Jung, the unconscious was partially collective, but for Bowen the conscious and unconscious was totally collective (Stinson, 2016).

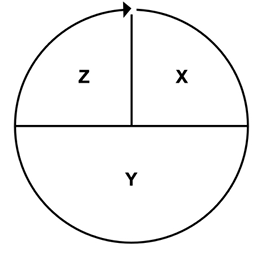

2. The hero’s journey

In the monomyth, Campbell (1949) describes the hero based on the route he takes through the different stages of a journey in seventeen stages, which will transform him from an ordinary person, into the bearer of justice for his community. In the extensive catalog that he describes in his work, he name the stories of the Buddha, Ulysses, the original African woman Massassi, Gilgamesh, Jesus or Quetzalcoatl, as some of the examples of universal characters who identify with the pattern of the hero’s journey, which is divided into three basic stages or acts of narration: separation from the world (X), penetration to a type of power source (Y) and return with a grown life (Z).

Figure 1. The Monomith Nuclear Unit

Source: Campbell (1949)

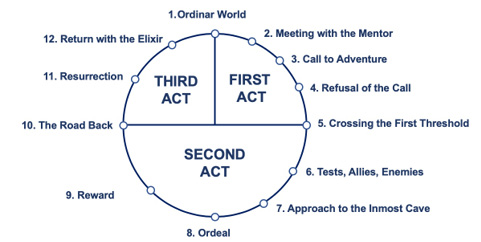

But the hero does not travel alone. Along his/her way he/she will meet different objects, events and characters that represent other archetypes and that complement the meaning of his/her story (the Mentor, the Guardian, the Shapeshifter, the Shadow, the Traitor), completing different steps that they will take him/her to the final destination. Jung had suggested that these archetypes are reflective of various aspects of the psyche, and that they reincarnate in our unconscious in characters to help us enact the drama of our lives. Decades later, writer and film producer Christopher Vogler (1998), in his book “The Writer’s Journey: Mythical Structures for Writers”, simplified Campbell’s steps to a total of twelve stages in three acts, delivering a guide that has worked as the benchmark par excellence to build stories that everyone can identify, understand and integrate into a modern narrative experience (including heroes such as Frodo Baggins, Luke Skywalker, James Bond, Wonder Woman or Bud Cassidy and the Sundance Kid).

Figure 2. The twelve stages of the hero’s journey

Source: Vogler (1998)

The hero is originally a character without any special attributes who lives in an ordinary world, but who undertakes a journey following a call (which he initially rejects), to enter another one unknown, full of powers, characters and strange events. Once crossed the threshold that separates him from his home world, the hero will face different tasks and tests, alone or with help. However, there is a key test that he/she must complete in order to overcome death and receive a reward. Then the hero will have to decide whether to return to the ordinary world with the obtained gift. If the hero decides to return, he/she will face new challenges on the way back to the ordinary world, including acceptance or not by those who have not left their original world. If the return is successful, the blessing or reward can be used to improve his/her people and bring justice. And yes, there’s a connection between the hero myth and the model of the entrepreneur as an agent of change of their cultural system. At some point in his extensive work, Campbell called the entrepreneur the ‘real hero’ in American capitalist society (Morong, 1992).

However, in this journey according to Campbell himself, returning with a grown life and integration with society is the most difficult requirement of all. In this final stage of reintegration, the hero resists giving up the image of superhuman talent and immortality. The author warns of heroes who refuse to accept his reintegration as mortals: “Today’s hero becomes the tyrant of tomorrow.” In his book “The Hero’s Farewell”, Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, based on the concept of Campbell, reflects on CEOs viewed from the hero’s perspective at the retirement stage. In this work we are warned that if heroes come to believe in the enduring supremacy of their own power and abilities, they will eventually destroy themselves. Founder’s family identity is closely linked to their identity as a company leader, family business founders often have a special sense of loss when power is transferred. They have attached themselves to their heroic stature as patriarchs of the family and of the firm and handing over one title means losing the other. By giving up control of the company, they feel like they’re giving up their position as head of the family, and this perspective is especially traumatic.

To resist the temptation to push the limits of his abilities too far, the CEO must accept two conditions for retirement: heroic stature and mission. Heroic stature or recognition refers to the unique position of power that has been earned on their own merits and that the main leaders have, allowing them to be above the rest of the individuals in the group. The heroic mission or legacy is the leader’s sense of having accomplished their mission in life and of being able to convey a message with a moral tied to their ultimate purpose, a unique ability to fulfill the responsibilities of its exclusive position as patriarch (Sonnenfeld, 1988).

3. The óscar centeno journey

Having the stages proposed by Vogler (1998) as a model to describe the hero’s journey, we present one of the last cases which we have worked in its narrative (fictional names and locations), using the timeline of sequences of landmarks, places, characters and values, among other data, identifying throughout the story of the family business history most of the phases, archetypes and steps of the protagonist’s journey: Óscar Centeno,Mexican architect founder of a real estate empire that arose from the effort of his dedication to work and the unconditional support of his wife, starting from a salary as a recent graduate professional in an office in Monterrey (Mexico), until leaving an estate valued today in more than 200 million US dollars. The collection of information is done during the professionalization consulting process of the Family Office of the family inheriting the wealth, led today by the second generation, in sessions where the data was sorted as the information was generated organically with the family members, with temporary leaps forward and backward, revealing, discovering and remembering the most important references and testimonies that were outlining the structure, important characters and their interactions, places, objects, business achievements and other facts of the environment that frame the entire narrative, until creating a coherent composition based on the model that we have previously explained. Here is a summary of the story told by the Centeno family:

Act One: Óscar was born in the 30s into a very humble farming family from a small town in northern Mexico, near the border with the United States (Ordinary World). Óscar, the youngest of eight brothers, always had the feeling that one day he would leave town and go to the big city to study a university degree. His brother Aurelio (the teacher’s archetype, the Meeting with the Mentor), five years older, had become his tutor by giving him advanced classes that he was not given at school. It was he who encouraged him to enroll in the Architecture school, supporting him financially so that he could complete his career. Upon graduating from college, he found a low-paying job in a Monterrey office and married shortly after Margarita Gómez, whom he met just before graduation. Aurelio arranged for his brother to receive a job offer in Tijuana (Call to Adventure), but Aurelio initially discarded it (Refusal of the Call), because he did not want to detach himself from the family of his wife with whom he got along very well, only support he had in a city where he had no relatives. Finally, he accepted the proposal because they doubled his salary offer and the young couple went to live with great hopes in a city they had never been before (Crossing of the First Threshold).

Act Two: From the beginning, Óscar stood out as a designer and supervisor of construction works in a buoyant city that was growing non-stop in the late 1960s. Always supported by his bosses and coworkers, not discounting any other member of the competition who wanted to take away the opportunities of new projects (Tests, allies, enemies), Óscar was breaking through creating a faultless professional prestige. In 1976, having raised a small capital, he decided to found his own construction company, starting with small orders for houses and commercial offices. Little by little, he found a niche in the high-end shopping malls of the city, until, in the early 80s, an American investment group arrived at Tijuana looking for a local partner who wanted to invest with them in the first mega mall of the city. Óscar had never be part of a project of such magnitude and complexity, but he never doubted that he and his company could meet the challenge. Pawning all his savings and looking for loans to be able to offer the economic guarantees that investors demanded, Óscar risked all of them in the project (Approach to the Inmost Cave). For three years they were working hard in construction, with great technological and economic challenges, to the point that Óscar had to be admitted to the hospital for overwork, six months before the opening of the mall: he almost died of a heart attack, because his heart had been subjected to a high level of stress. From the window of his hospital room, he reflected on the fragility of his health, the well-being of his family and the future of the company. Finally, making a great effort, he returned to work and led the final phase of the project (Ordeal). With this business achievement, and having exceeded the forecasts of economic benefits, Oscar’s company positioned itself as the undisputed construction leader in the region, reaping successes and attracting significant investment capital (Reward). However, his health was never the same again. An unfortunate fact that made it notably worse was the betrayal of his secretary (the archetype of the shapeshifter), who managed to flee the country with several thousand dollars that he stole from the funds of one of the projects, which plunged Oscar into a depressive state, despite the fact that his company recovered without any problem, since two of his sons had already joined the company’s management, helping him to lead it and to diversify investments. Finally, and against his iron will to continue in command, he decided to withdraw completely from the operation and move to a more passive plane, in accordance with the recognition of his hierarchical status and more convenient for his health (The Road Back).

Act Three: He returned to caring for his wife, whom he had neglected for the past two decades, retiring to a ranch on the outskirts of the city. From there he created a foundation that would bear his name to support young talents who needed financial support to complete their architectural studies (Resurrection). After her death in 2015, her children (who now run the Family Office and family businesses), as well as her grandchildren, have ensured that the community can continue to enjoy his legacy through the publication of his writings and reflections, as well as his generosity and justice, giving life and continuity to the Óscar Centeno Foundation (Return with the Elixir).

4. Making the unconscious conscious

The case study explained above is an example of the power of creative direction in the construction of family storytelling, which helps us to order and give coherent meaning to the story and its message and values. Some of these collected lessons can be:

For the founders For the next generations

The hero must return. We can all be a hero.

You must share the It is okay to be afraid.

elixir with others.

You will leave a legacy. You will have help.

You’re not alone.

You deserve A defeat is not the

recognition. end of the road.

Beyond the cohesive functionality of myth in the family system, its creative capacity allows us to make sense of reality and build a meaningful future. From a neurological point of view, the same machinery that brings together all the pieces to relive the past, can put some of them together with other pieces to simulate futures. The brain interweaves memories of the past and dreams of the future to create the sense of ‘I’ (Seekamp, 2019). Once one learns to flow with images in a more abstract way, a more flexible psyche will begin to develop. Symbolic thinking is the art of hypothesis. Understanding and acknowledging the past proposes a way to validate the entire human experience and paves the way for creativity and flexibility. According to Lansberg (2020) “as a species, we are too limited to imagine a world we don’t know much about”. This inclusive and exploratory approach reveals countless avenues for better relationships, less conflict, and a more efficient way of working as a group.

Jaskiewicz et al. (2015) confirm that only recently researchers studying highly innovative family businesses have revealed that, a shared family and business history passed down from generation to generation can positively influence the level of family business innovation, as stories with a strong focus on past achievements and resilience are passed on to subsequent generations, thereby fostering transgenerational entrepreneurship. The ability to generate stories directly depends on the ability to listen. In every encounter in which we reconstruct the account of the common past, participants are required with the capability to question and express curiosity even about a painful past, combined with the capacity for compassion and empathy. Interviewers and social listeners are required, committed to preserving memory, but also attentive to the subjective processes of those who are invited to narrate; and this is not always possible (Jelin, 2001). That is why our role as guides to a process that by being creative is both moldable and healing is important. In Campbell’s words “A myth cannot be artificially created or destroyed, but it can be modified” (Campbell, 1949).

5. Conclusions

As mentioned in the introduction, applying the Hero’s Journey model for understanding the principles of the family business culture and leading powerful creative conversations while constructing the family origins can help us to order and give coherent meaning to the story and its message and values. Storytelling in general allows us to provide business families with learning that remains impressed on their consciousness using their own languages. It is not the experience of life itself, but the meaning we give it. Once we understand that, we have the ability to change history and reality. “The secret is: know yourself (know your family!)” (Fokker, 2019). The hero’s journey in particular as a healing tool is based on the power of the monomite, pieces of information that have supported the life of man, civilizations and religions formed throughout the millennia, and have to do with deep internal problems, internal mysteries, thresholds of passage. Concerns such as “I cannot be better than my predecessors”, or “I want to do something with meaning” or “I do not deserve the wealth I have” or “My gifts are not appreciated and my legacy is in danger” can be results understanding the origin and destiny of the identity of the individual in the collective story. In the words of Joseph Campbell (1949): “Myths are clues to the spiritual potential of human life.”

Whether we listen with aloof amusement to the history of the commercialization of an invention in the 19th century United States or read with cultivated rapture the autobiography of a pioneer of electronic commerce in contemporary China or catch suddenly the shining meaning of the history of the founding of a supermarket by European immigrants in Costa Rica in the 1950s, it will always be the one, shape-shifting yet marvelously constant story that we find.

References

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. The Joseph Campbell Foundation. New World Library. Novato, CA. 3rd Edition.

Denison, D., Lief, C., & Ward, J. L. (2004). Culture in family-owned enterprises: recognizing and leveraging unique strengths. Family Business Review, 17(1), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00004.x

Fokker, L. (2019). The role of storytelling in aligning family and wealth. Trusted Family Webinars. Brussels, Belgium. https://trustedfamily.net/insights/2019/8/1/the-role-of-storytelling-in-aligning-family-and-wealth

Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.001

Jelin, E. (2001). Los trabajos de la memoria. Siglo XXI de España Editores. Madrid, Spain.

Kammerlander, N., Dessi, C., Bird, M., Floris, M., & Murru, A. (2015). The impact of shared stories on family firm innovation: a multicase study. Family Business Review, 28(4), 332-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515607777

Lansberg, I. (2020). What do the owners want? How business families think about their future. Trusted Family Webinars. Brussels, Belgium. https://trustedfamily.net/insights/2020/1/31/what-do-the-owners-want-how-business-families-think-about-their-future.

Morong, C. (1992). The creative-destroyers: are entrepreneurs mythological heroes? Presented at the Western Economic Association Meetings in San Francisco. http://cyrilmorong.com/CreativeDestroyers.pdf

Ruffiot, A. (1980). La Función Mitopoiética de la Familia: Mito, Fantasma, Delirio y su Génesis. In Homenaje a André Ruffiot. Psicoanálisis & Intersubjetividad, 8-2015. https://www.intersubjetividad.com.ar/numero-8/

Salazar, G. (2019). Working with family diagrams in family business: reflections from 20 years of practice. FFI Practitioner. The Family Firm Institute. Boston, MA. https://digital.ffi.org/editions/working-with-family-diagrams-in-family-business-reflections-from-20-years-of-practice/

Seekamp, D. (Ed.) (2019). The mind explained: memory. Original Netflix Documentary Production. [Video file]. Retrieved from: https://www.netflix.com/search?q=The%20mind%20explained%3A&jbv=81098586

Sonnenfeld, J. (1988). The hero’s farewell. What happens when CEOs retire. Oxford University Press. New York, NY.

Stinson, P. (2016). Jung was ‘Thinking Systems’: a juxtaposition of Jungian Psychology and Murray Bowen’s family systems theory. PSY 7174 History & Systems of Psychology. California Institute of Integral Studies.

Vogler, C. (1998). The writer’s journey: mythic structure for writers. 3rd Edition. Michael Wiese Productions. Studio City, CA.