European Journal of Family Business (2022) 12, 1-12

Employee Silence and Entrepreneurial Orientation in Small and

Medium-sized Family Firms

Duarte Pimentelab* Raquel Rodriguesc

a Centro de Estudos de Economia Aplicada do Atlântico (CEEAplA), University of the Azores, Portugal

b TERINOV – Parque de Ciência e Tecnologia da Ilha Terceira, Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal

c Instituto Superior de Psicologia Aplicada, Lisboa, Portugal

Research paper. Received: 2021-09-22; accepted: 2022-03-04

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10

KEYWORDS

Family firms, Portuguese companies, Employee silence, Entrepreneurial orientation

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresas familiares, Empresas portuguesas, Silencio de los empleados, Orientación emprendedora

Abstract This paper aims to assess differences between employees of family and non-family firms regarding their levels of employee silence and their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation. Moreover, focusing on family firms, we assess the relationship between the levels of employees’ silence and their perceptions of the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. The empirical evidence is provided by a sample of 245 Portuguese employees, 117 employees of family firms, and 128 of non-family firms, who responded to a questionnaire that included employee silence and entrepreneurial orientation measures. Results reveal that family firms’ employees show higher levels of employee silence but perceive their companies as less entrepreneurially oriented than employees of non-family companies. In addition, our results do not support the idea that there is a relationship between the levels of employee silence and the employee’s perception of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation. This paper offers initial insights into the debate on the relationship between the levels of employee silence and the employee’s perception of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation in family firms.

El silencio de los empleados y la orientación emprendedora en pequeñas y medianas

empresas familiares

Resumen Este trabajo tiene como objetivo evaluar las diferencias entre los empleados de empresas familiares y no familiares en cuanto a sus niveles de silencio de los empleados y sus percepciones de la orientación empresarial de la empresa. Además, centrándonos en las empresas familiares, evaluamos la relación entre los niveles de silencio de los empleados y sus percepciones sobre la orientación emprendedora de la empresa. La evidencia empírica la proporciona una muestra de 245 empleados portugueses, 117 empleados de empresas familiares y 128 de empresas no familiares, que respondieron a un cuestionario que incluía medidas de silencio de los empleados y orientación empresarial. Los resultados revelan que los empleados de las empresas familiares muestran niveles más altos de silencio de los empleados, pero perciben a sus empresas como menos orientadas al emprendimiento que los empleados de empresas no familiares. Además, nuestros resultados no apoyan la idea de que exista una relación entre los niveles de silencio de los empleados y la percepción de los empleados sobre la orientación emprendedora de la empresa. Este artículo ofrece una primera mirada al debate sobre la relación entre los niveles de silencio de los empleados y la percepción de los empleados sobre la orientación emprendedora de la empresa en las empresas familiares.

https://10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i1.13017

Copyright 2022: Duarte Pimentel, Raquel Rodrigues

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author:

E-mail: duartengpimentel@gmail.com

1. Introduction

In a global and highly competitive economic environment, companies increasingly rely on their workforce expertise and ability to meet the market needs by innovating and enhancing the quality of their products and services (Soomro & Shah, 2019). This becomes even more relevant when it comes to small and medium-sized family companies, which heavily depend on employees who take responsibility, are proactive, offer suggestions, and openly share their ideas and opinions. However, given their traditions, norms, and values, these companies can sometimes hinder this so needed open environment, resulting in employee silence (Kizildag, 2013). Employee silence is defined as the intentional withholding of ideas, information, and opinions with relevance to improvements in work and work organizations (Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Wang et al., 2020). When individuals and teams are unhindered by organizational traditions, and norms, they can more effectively investigate, share, and develop new ideas, playing a critical role in the entrepreneurial orientation of a company, which has “become a popular means to describe entrepreneurship as an organizational attribute” (Wales et al., 2020, p. 2), in the hopes of doing something new and exploiting opportunities. The benefits of adopting such entrepreneurial behaviors and strategies include the generation of new ideas and creative processes, improving a firm’s competitive position and may even be crucial to a firm’s survival (Covin & Wales, 2012).

Family businesses recognize that employees are their life force and strive to develop an inclusive work culture (Miller et al., 2008) and to create and retain a motivated and loyal workforce (Kachaner et al., 2012). However, due to the aforementioned organizational traditions and norms and the well-known family firms’ concern over the preservation of socioemotional wealth, i.e., “the non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty” (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007, p. 106), these firms tend to maintain the decision-making processes within the family top management ranks (Pimentel et al., 2018), fostering employee silence and hindering entrepreneurial behaviors.

Previous studies have highlighted the importance of promoting and implementing an entrepreneurial oriented mindset that makes small and medium-sized companies able to recognize the threats and opportunities in their business environment in order to make sure that the firm will be able to continue to exist in the future (Kraus et al., 2012). The need to survive and to perpetuate the family values plays a central role in the family businesses dynamics given its strong connection to the preservation of socioemotional wealth (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Nevertheless, companies are only able to promote and implement such entrepreneurial oriented mindset if there is an open and fluid communication between employees and the top management team. If this communication is hindered it can create a barrier to the upward communication, leaving the organizational decision makers unaware of the ground realities and problems of the company, resulting in problems to prompt and adequate decision making, further leading to depleted organizational performance with consequences in the survival of the company (Schilling & Kluge, 2009). Therefore, it becomes essential to address employee silence in family firms and to view it as a priority for promoting and implementing an entrepreneurial orientated mindset, determinant for the family firms’ success. With this in mind and grounded on the socioemotional wealth theory (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007), oftentimes accepted as the dominant paradigm in the field of family business (Aparicio et al., 2021; Berrone et al., 2012), we performed an empirical study using data collected from family firms from Portugal, a country where family firms are under-researched even though they make up the backbone of the economy. This paper has three main objectives: (1) assess differences between the levels of employee silence in family and non-family firms, (2) examine the perceptions of the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation of employees working in family and non-family firms, and (3) assess, in family firms, the relationship between the levels of employees’ silence and their perceptions on the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation.

This study makes several contributions to the research literature. First, we offer initial insights on a phenomenon that remains under-addressed in the comparison between family and non-family companies - employee silence. Second, we contribute to a current debate in the literature involving the extent to which the characteristics and dynamics of family companies hinder or promote entrepreneurial behaviors and strategies. Third, we search for evidence to support the relationship of employer silence and entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Answering these questions is important given that family businesses are a predominant form of business in the world, accounting for over two-thirds of all private companies, employing more than 60% of the global workforce and having an economic impact of over 70% on the global GDP (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2018).

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Employee silence

Van Dyne et al. (2003) define employee silence as an employee’s motivation to withhold or express ideas, information, and opinions about work‐related improvements. Thus, it refers to situations where employees retain information that might be useful to the organization of which they are a part, whether intentionally or unintentionally; information can be consciously held back by employees; or it can be an unintentional failure to communicate or a merely a matter of having nothing to say (Wang et al., 2020). This reluctance to express ideas, information, and opinions may be caused by individual employee motivations or by institutional aspects (Chou & Chang, 2020). Regardless of the reasons for employee silence, it can undermine organizational decision-making, damage employee engagement, trust, and morale, which may lead to low levels of motivation, satisfaction, and commitment (Morrison & Milliken, 2000).

Modern organizations are often challenged to adequately respond to complex and changing scenarios. Thus, developing a workforce that openly shares information, ideas, and opinions, constitutes a significant competitive advantage, allowing companies to better adjust to contingency forces and make better decisions (Wilkinson & Fay, 2011).

Van Dyne et al. (2003) differentiate three specific silence behaviors based on three employee motives: (1) acquiescent silence, (2) defensive silence, and (3) pro-social silence.

According to Pinder and Harlos (2001), acquiescent silence can be defined as the employee choice to withhold views, relevant ideas, information, or opinions, based on resignation. Acquiescent silence is a passive behavior given that it advocates disengaged behavior (Van Dyne et al., 2003). In the case of acquiescent silence, employees commend the status quo and prefer not to speak up. They do not try to change organizational circumstances. This is a conscious choice and voluntary behavior that the employees adopt when they believe that speaking up will not make any difference.

The term defensive silence is employed to describe the deliberate omission based on personal fear of the consequences of speaking up. This is consistent with Morrison and Milliken’s (2000) emphasis on the personal emotion of fear as a key motivator of organizational silence. It is also consistent with psychological safety and voice opportunity as critical preconditions for speaking up in work contexts. According to Van Dyne et al. (2003), this is an intentional behavior that is intended to protect one’s self from external threats. In contrast to acquiescent silence, defensive silence is proactive, involving awareness and consideration of alternatives, followed by a conscious decision to withhold ideas, information, and opinions as to the best personal strategy at that a particular moment (Chou & Chang, 2020; Van Dyne et al., 2003).

Van Dyne et al. (2003) emphasized pro-social silence as the withholding of related ideas, information, or opinions with the intention of benefiting other people or the organization, based on altruism or cooperative motives. Similarly, to organizational citizenship behavior, pro-social silence is an intentional and proactive behavior that is primarily focused on others, arising as a discretionary behavior that cannot be mandated by an organization and based on awareness and consideration of alternatives and resulting in the conscious decision to withhold ideas, information, and opinions.

Despite the growing importance of employee silence in the literature, given its direct impact on individuals, organizations, and ultimately on society, there is still an significant gap in the understanding of this organizational phenomenon (Wang et al., 2020; Whiteside & Barclay, 2013). This gap becomes even more pronounced in the family business field, where the literature on this topic is scant. One of the few authors addressing this topic in family firms is Kizildag (2013), who suggests that employee silence in family firms can be approached from two different dimensions: (1) silence of employees who are not members of the family, and (2) silence of employees who are family members. When assessed from the perspective of employees who are not family members, experiencing nepotism and family protectionism will cause these employees to perceive the expression of their ideas and opinions as meaningless. On the other hand, from the perspective of employees who are family members, having a dual role of being a family member and a family firm employee, having responsibilities to fulfill both family and business expectations, as well as the reflection of family relations on the workplace, are reasons for adopting a silence strategy. Moreover, the existence of a traditional centralized management, oftentimes related to the need to preserve socioemotional wealth and subsequently the perpetuation of family values (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) may foster the silence of both family members and non-family employees. Kellermanns et al. (2012) argue that socioemotional wealth can be negatively associated with proactive stakeholder engagement and lead to family-centric behavior, which may act as a blockade to inputs from non-family employees and other external stakeholders. Moreover, some case-based family firm literature report stories of family firms that have ignored non-family stakeholders (e.g., Kidwell & Kidwell, 2010). Family firms have also been known to expropriate external shareholders and, in more extreme cases, to exploit employees (Kidwell, 2008). According to Kellermanns et al. (2012) strong family bonds can create an “us-against-them” mindset causing the family to place their needs above those of non-family stakeholders. Taking this into consideration, one can argue that family firms have characteristics and dynamics that contribute to higher levels of employee silence. Thus, as an initial contribution to the literature on this topic, we propose that:

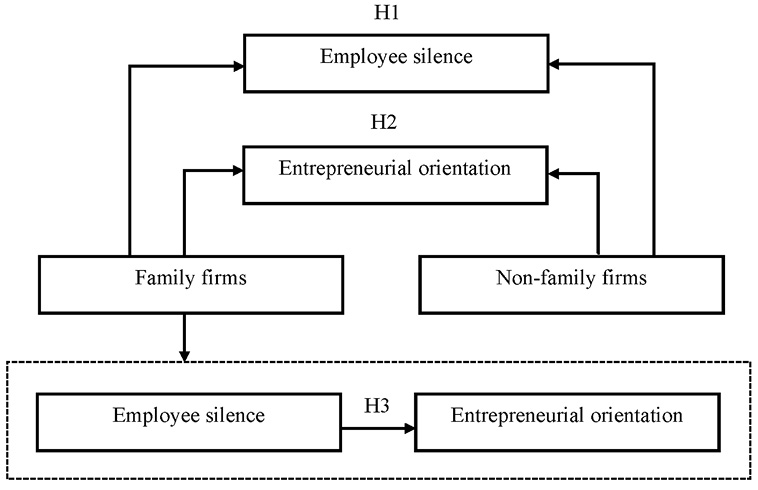

H1. Family firms’ employees show higher levels of silence than non-family firms’ employees.

2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation

As any living entity, a company’s main goal is to survive. In its continuous interaction with the environment, a company must guarantee the development of services and/or products that respond to the consumers’ wants and needs, while considering the surrounding competitive conditions (Josefy et al., 2017). In an environment of permanent change, with products and business models with short life cycles, companies feel obliged to constantly search for new business opportunities. This forces companies to seek and adopt entrepreneurial behaviors to succeed (Rauch et al., 2009). Although entrepreneurship remains an area of numerous conceptual debates, certain ideas surrounding this construct have been extensively developed. There has been a great stream of research on what is, for many, considered the genesis of entrepreneurship: the entrepreneurial orientation (Rauch et al., 2009).

Entrepreneurial orientation refers to the processes and endeavors of organizations that engage in entrepreneurial behaviors and activities (Covin & Wales, 2012; Lumpkin & Dess, 2001). The concept stems from Miller’s (1983) work, in which entrepreneurial firms are defined as “those that are geared towards innovation in the product-market field by carrying out risky initiatives, and which are the first to develop innovations in a proactive way in an attempt to defeat their competitors” (p. 771). Although there have been various discussions about what constitutes entrepreneurial orientation (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005), research has converged on three key components (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2011): (1) innovativeness, (2) risk-taking, and (3) proactiveness.

Over the last decades, entrepreneurial orientation has been seen as critical to the success and survival of family businesses (Nieto et al., 2015). Research on entrepreneurial orientation in family businesses is divided into two perspectives: on one hand, the perspective where this type of organizations represents a context in which entrepreneurship is fostered (Hernández-Perlines et al., 2021); on the other hand, the perspective where family firms hinder entrepreneurial processes (Hernández-Linares & López-Fernández, 2018).

While some authors propose that family firms constitute an environment that promotes high levels of entrepreneurship (e.g., Aldrich & Cliff, 2003; Discua Cruz et al., 2013; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2021), by presenting unique settings for entrepreneurship to flourish (e.g., flexibility, trust, informal management) (Eddleston et al., 2008; Zellweger, 2007). Other research stream suggests that family firms are conservative and resistant to change, due to the perceived risk of losing family socioemotional wealth created over a long period (Boling et al., 2016; Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2016). Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007) argue that family firms may be willing to accept a below-target performance, if this is what it takes to protect their socioemotional wealth. Hence, their focus is centered on what can go wrong and on the likelihood that bad things may occur. Such concerns tend to hamper the promotion and implementation of an entrepreneurial mindset. Pimentel et al. (2017a) reinforce this prominent notion in the literature, which suggests that family businesses are risk-averse, reluctant to innovation, and reticent (Samsami & Schøtt, 2021), therefore showing lower levels of entrepreneurial orientation than non-family businesses. Thus, as to offer more insights on this topic, our second hypothesis suggests that:

H2. Family firms’ employees perceive their company as less entrepreneurially oriented than non-family firms’ employees.

As aforementioned, the adoption of silence restricts the access to useful information and critical analysis on the decision-making process, decreasing the effectiveness and quality of decision-making (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). Similarly, employee silence will inhibit feedback on valuable information, thus making the identification of issues and the implementation of corrective actions more difficult. This may translate into a decline in the organization’s performance and ability to adapt and survive. Edmondson (2003) argues that employee silence will hinder family businesses’ innovation processes, since this type of firm heavily relies on employees to point out new ideas, thoughts, and opportunities. In the same line, Knoll and Redman (2016) suggest that the inability of employees to share ideas and provide inputs may also hinder innovation and stifle employee creativity. Thus, the withholding of this information prevents improvements to processes and projects, constraining the entrepreneurial orientation of the organization and ultimately the chances to thrive and succeed.

Thus, based on the same rationale used on the previous hypotheses, and as an initial attempt to assess the association between the employees’ levels of silence and their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation in family firms, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H3. In family firms, the employees’ levels of silence are negatively related to their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation.

3. Sample Description and Methods

3.1. Sample and data collection

In this study, as in most research, employee silence and entrepreneurial orientation have been regarded as broad and unitary constructs (Covin & Wales, 2019; Morgan, 2017), enabling an initial explanation of the phenomena. To define what is a family firm, the criterion of ownership and management control (Chua et al., 1999) was adapted to arrive at an operational definition. Therefore, a firm is classified as a family firm if at least 75 percent of the shares are owned by the family, and the family is the sole responsible for the management of the company. This operational definition ensures that the family is, de facto, responsible for the governance, control, and management of the company (Pimentel, 2018; Pimentel et al., 2020).

In order to collect data, employees were asked to complete an online questionnaire, assessing employee silence levels and entrepreneurial orientation perceptions as well as respondents’ demographic data. A cross-sectional design was used, according to Spector (2019), the use of these types of designs is particularly efficient when compared to others such as experimental design or longitudinal design, being particularly relevant in situations where the probability of obtaining high levels of response (i.e., a large sample) is low (Spector, 2019). During the questionnaire development precautions were taken to control common method bias, namely, to improve scale items to eliminate ambiguity, and to reduce social desirability bias in item wording (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Figure 1. Research hypotheses diagram

Data from family firms’ employees were collected with the help of the Portuguese Family Business Association, which shared the survey link via e-mail and institutional website with their associated members. As to collect data from non-family companies’ employees, the survey link was shared through e-mail using a publicly available business mailing list. The data were collected between November 2019 and January 2020. In Portugal, family firms are responsible for over 50% of all employment, 65% of GDP, and constitute more than 70% of the private business sector (Portuguese Family Business Association, 2021). According to Pimentel et al. (2017b), most Portuguese family firms operate in the retail sector, have less than 10 employees, have been in business for roughly 30 years, and have a turnover of less than €500,000 per year. The employees show a strong sense of pride, belief, and identity towards the firm, and consider that the family has a far-reaching influence in the business (Pimentel, 2016; Pimentel et al., 2017b).

The final sample consists of the responses of 245 Portuguese employees. Of the 245 employees who participated in this study (see Table 1), 117 are employees of family firms and 128 non-family firms’ employees, 58.4% of them were females, with an average age of 34 years, having on average 7 years of seniority in the company. Most participants have a high school diploma (38.4%), followed by the ones with a bachelor’s degree (33.9%), while 25.3% have a master’s degree and 2.4% hold a PhD. Regarding the work contracts, 122 have a permanent contract, 43 a fixed-term contract, and 80 are on temporary work contracts. From the 117 employees of family firms, most were female (56.6%), with an average of 32 years, overall working in the company for 8 years. Regarding the 128 non-family firms’ employees, 59.6% were females, with an average age of 36 years and working in the company for 6 years.

All the 245 respondents are employees of small and medium-sized privately-owned companies with no less than 10 employees, having no management responsibilities, and working under the responsibility of a supervisor who holds direct formal authority over them.

|

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of sample demographic characteristics |

|||

|

Groups |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

143 |

58.4% |

|

Male |

102 |

41.6% |

|

|

Age of the respondente |

18 - 25 years |

15 |

6.2% |

|

26 - 41 years |

187 |

76.3% |

|

|

42 - 57 years |

30 |

12.2% |

|

|

58 years and above |

13 |

5.3% |

|

|

Seniority |

0 - 5 years |

73 |

29.8% |

|

5 - 10 years |

103 |

42.1% |

|

|

10 - 15 years |

51 |

20.8% |

|

|

15 years and above |

18 |

7.3% |

|

|

Education |

High school diploma |

94 |

38.4% |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

83 |

33.9% |

|

|

Master’s degree |

62 |

25.3% |

|

|

PhD degree |

6 |

2.4% |

|

|

Employment contract type |

Temporary work contract |

80 |

32.7% |

|

Fixed term work contract |

43 |

17.5% |

|

|

Permanent work contract |

122 |

49.8% |

|

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Employee silence

To measure the levels of employee silence, the Portuguese adapted version (Sabino et al., 2019) of the scale originally developed by Van Dyne et al. (2003) was used. This version of the instrument considers three dimensions: (1) acquiescent silence (i.e., “I passively keep problem-solving ideas to myself.”; “I keep ideas for improvement to myself because I have little self-confidence that it will make a difference.”; “I am not willing to make suggestions for change because I am not very committed.”; “I hold back ideas on how to improve the work around me because I am under-engaged.”; and “I passively withhold ideas because I am resigned.”), (2) defensive silence (i.e., “I avoid expressing ideas for improvements to protect myself.”; “I withhold relevant information because I am afraid.”; “I omit important facts in order to protect myself.”; “I do not express or suggest ideas for change because I am afraid.”; and “I withhold the solution to problems because I am afraid.”), and (3) pro-social silence (i.e., “I protect information to benefit the organization.”; “I withhold confidential information because I am cooperative.”; “I refuse to disclose information that could harm the organization.”; “I resist pressure from others to share organizational secrets.”; and “I adequately protect confidential information out of concern for the organization.”). The response of this fifteen-item questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale, 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated, and its value was found to be 0.84.

3.2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation

While several measures of entrepreneurial orientation exist, we relied on the Portuguese adapted version (Pimentel et al., 2017a) of the widely used instrument developed by Covin and Slevin (1989). This choice increases the comparability of our findings, given that most of the empirical research has employed this approach (Covin & Wales, 2012). The response of this nine-item questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale, 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), on which the respondent should indicate the extent to which the items represent their firm’s strategy. The entrepreneurial orientation questionnaire distinguished three dimensions: (1) innovativeness (“In general, the top managers of my firm favor a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations.”; “In the past five years our firm has marketed many new lines of products or services.”; and “In the past five years changes in our products or services lines have usually been quite dramatic.”), (2) risk-taking (“In general, the top managers of my firm have a strong proclivity for high-risk projects (with chances of very high returns).”; “In general, the top managers of my firm believe that owing to the nature of the environment, bold, wide-ranging acts are necessary to achieve the firm’s objectives.”; and “When confronted with decision-making situations involving uncertainty, my firm typically adopts a bold, aggressive posture in order to maximize the probability of exploiting potential opportunities.”), and (3) proactiveness (“In dealing with its competitors, my firm typically adopts a very competitive, “undo-the-competitors” posture.”; “In dealing with its competitors, my firm is very often the first business to introduce new products/services, administrative techniques, operating technologies, etc”; and “In dealing with its competitors, my firm typically initiates actions to which competitors then respond.”). Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated, and its value was found to be 0.86.

3.2.3. Demographic data

In order to collect demographic data from the respondents, a short questionnaire was included in the survey. The questionnaire was comprised of six items: gender, age, seniority, education, and employment contract type.

4. Results

Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics and inferential statistics (i.e., independent samples t-test and simple linear regression). Further, the SPSS Statistics 27 Software was utilized for data analysis and p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation of the demographics and variables used, in addition to the correlation coefficients between them. It is observed that the age of the employees has a negative correlation with employee silence levels (r = - 0.167; p = 0.017) and is also negatively correlated with the employee’s perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation (r = - 0.172; p = 0.013). Moreover, the results also reveal a negative correlation between the seniority of the employee and employee silence levels (r = - 0.193; p = 0.012).

|

Table 2. Means, standard deviations and correlations between variables |

|||||||

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Age of the respondent |

Seniority |

Employment contract type |

Education |

Employee silence |

|

Age of the respondente |

34.05 |

11.87 |

1 |

||||

|

Seniority |

6.98 |

9.07 |

0.768** |

1 |

|||

|

Employment contract type |

2.73 |

0.58 |

0.482** |

0.453** |

1 |

||

|

Education |

2.23 |

0.43 |

- 0.107 |

0.112 |

0.101 |

1 |

|

|

Employee slience |

3.28 |

0.92 |

- 0.167* |

- 0.193* |

- 0.055 |

0.110 |

1 |

|

Entrepreneurial orientation |

2.95 |

0.83 |

- 0.172* |

- 0.147 |

- 0.117 |

0.132 |

0.457 |

|

N = 245;*p < .05; ** p < .001 |

|||||||

Means comparison and t-test were conducted to test our first hypothesis, which suggests that there are differences between employees of family and non-family firms regarding the levels of employee silence. T-test analysis for independent groups (see Table 3) shows that there are differences regarding the levels of employee silence between family (M = 3.62, SD = 0.97) and non-family businesses (M = 3.06, SD = 0.79), t (178.36) = - 4.61; p = 0.00, d = 0.63.

|

Table 3. T-test: employee silence levels in family and non-family firms. |

|||||||

|

T |

P |

Df |

Family firms |

Non-family firms |

|||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

||||

|

Employee silence |

- 4.61 |

0.00* |

178.36 |

3.62 |

0.97 |

3.06 |

0.79 |

|

N = 245; *p < .05 |

|||||||

Our second hypothesis proposes that family firms’ employees perceive their company as less entrepreneurially oriented than non-family firms’ employees. T-test results show significant differences regarding the levels of entrepreneurial orientation between family (M = 2.90, SD = 0.91) and non-family firms (M = 3.12, SD = 0.71), t (238.28) = 0.95; p = 0.02, d = 0.27 (see Table 4). Thus, confirming the hypothesis.

|

Table 4. T-test: perceptions of entrepreneurial orientation levels in family and non-family firms. |

|||||||

|

T |

P |

Df |

Family firms |

Non-family firms |

|||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

||||

|

Entrepreneurial orientation |

0.95 |

0.02* |

238.28 |

2.90 |

0.91 |

3.12 |

0.71 |

|

N = 245; *p < .05 |

|||||||

Hypothesis 3 posits that in family firms, the employees’ levels of silence are negatively related to their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation. Simple regression analysis results (see Table 5) do not support the hypotheses (t = 0.44, ß = 0.03, R² = 0.002, p = 0.66). Thus, the hypothesis is not confirmed.

|

Table 5. Regression results: employee silence and entrepreneurial orientation levels in family firms. |

|||||||

|

Independent variable |

Dependent variable |

R2 |

F |

ß |

t |

P |

|

|

Employee silence |

Entrepreneurial orientation |

0.002 |

0.19 |

0.03 |

0.44 |

0.66 |

|

|

N = 117 |

|||||||

5. Discussion

In this study, we seek to explore and assess if there are differences between family and non-family firms regarding the employees’ levels of silence and their perceptions on the company’s entrepreneurial orientation and to understand, within family firms, the association between these two variables.

Our first hypothesis proposed that there are differences between employees of family and non-family firms regarding the levels of employee silence. Results confirm that there are differences between these two types of companies. The presence of family kindship promotes a moral order to treat parents, siblings, cousins, and acquaintances with higher levels of altruism (Pimentel et al., 2021). Maintaining high levels of altruism-based relationships strengthens the family members’ orientation towards protectionism and family stability (Pimentel et al., 2018). According to Perlow and Williams (2003), this may act as an, deeply rooted, informal rule, that impels employees to be silent to avoid embarrassment, confrontations, and conflicts. Thus, it can be assumed that in family firms, this orientation towards the protectionism of the family may foster the adoption of silence as a strategy to cope with relationships between the family and the employees and, consequently, to guarantee the preservation of the company’s socioemotional wealth via the securing of the family emotional involvement.

Socioemotional wealth can also be seen as a driver of self-serving behavior and explain why some family firms place family needs and wants above those of other stakeholders such as non-family employees. It has also been found that because relinquishing socioemotional wealth is perceived as a major loss, family firms oftentimes ignore contributions from non-family stakeholders (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Similarly, Morrison and Milliken (2000) suggest that the high centralization of decision-making and the lack of formal upward feedback mechanisms may reinforce employee silence. Small and medium-sized family firms are structured in a way that gives owners and top managers the sole authority and initiative in the decision-making process. If owners and managers feel that their employees are untrustworthy, they adopt an autocratic rather than a participative management style. Since an autocratic management style does not involve most employees in the decision-making process, it may be a reason for high levels of employee silence. In traditional family firms, where values such as respecting elders and avoiding conflict are uncontested, silence is normally assessed as a virtue. In such a situation, employees prefer to remain silent and approve their superiors (Perlow & Williams, 2003; Wang et al., 2020).

Our second hypothesis proposes that family firms’ employees perceive their company as less entrepreneurially oriented than employees of non-family firms. Results confirm the hypothesis corroborating a growing stream of research that suggests that family businesses hinders entrepreneurial orientation (e.g., Alayo et al., 2019; Pimentel et al., 2017a). According to Duran et al. (2016), family firms have often been portrayed as traditional organizations that shy away from seeking new opportunities, follow conservative strategies, and that ultimately are less entrepreneurial than non-family companies. Over the last years several authors have argued that family dynamics and factors such as traditions, values, and customs, may have weakened the entrepreneurial mindset in family businesses, making these companies lag behind their non-family peers (e.g., Short et al. 2009; Pimentel et al., 2017a). The need to preserve these traditions, values, and customs, which are the grounds of socioemotional wealth, translates into the stability of non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). This so needed stability puts family members’ needs and preferences above the company’s financial performance (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007), which can block proclivity for high-risk projects associated with entrepreneurial activities. Furthermore, our results corroborate a prominent notion in the literature suggesting that family firms are risk-averse, reluctant to innovate, and slow to change, thus less entrepreneurial oriented than non-family firms (Naldi et al., 2007).

Addressing our third hypothesis proposes that in family firms, the employees’ levels of silence are negatively related to their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation. Results do not confirm this idea, showing that the employees’ levels of silence are not associated with their perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation levels. A possible explanation may be the fact that most employees tend not to allow that the adoption of an individual behavior (i.e., silence) influences their perceptions of a macro-organizational variable, such as the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. This may be related to coping strategies (e.g., positive reinterpretation) adopted by the employees, which involve the reappraisal of situations to see them in a positive light. Positive reinterpretation has been associated with optimism and positive beliefs (Carver et al., 1989). The ability to see the positive aspects of situations perceived as stressful (i.e., adoption of certain silence strategies) may aid the enhancement of an optimistic outlook, translating into the ability to distinguish individual perceptions from organizational strategies. Moreover, entrepreneurial orientation involves the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities to introduce new products or services to the market (Soriano & Huarng, 2013) resulting mostly from managerial decisions in which most employees are not involved. This may also help explain our results given that none of the participants have management responsibilities.

6. Conclusions and Practical Implications

The significance of studying employee silence in small and medium-sized family firms lies in the argument that in modern economic contexts, these businesses strongly rely on employee participation to survive. This same rationale also applies to entrepreneurial orientation, since it is a good predictor of the success of family firms, positively influencing their performance and success.

The paper contributes to the literature on family businesses, by revealing that employees of family firms show higher levels of employee silence than non-family firms’ employees. which may have a significant impact in small and medium-sized family companies, where the contributions and inputs of employees are of the utmost importance to the company’s development and survival. It was also possible to conclude that employees of family firms perceive their company as less entrepreneurially oriented than those of non-family firms. Besides supporting a prominent notion in the literature that suggests that family firms hinder the adoption of entrepreneurial behaviors and strategies, these results may also alert family businesses owners and managers about the importance of cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset that both enhances the output of the company and boosts the odds for success. Thus, also having positive outcomes on their workforce.

Moreover, although the results do not support the idea that, in family firms, there is an association between the levels of employee silence and the employees’ perceptions of the company’s entrepreneurial orientation, these initial findings can provide a steppingstone for future research in a field that holds wide theoretical and practical implications.

These findings may serve to alert owners and managers of small and medium-sized family companies to become of the importance to promote an environment that allows employees to express their ideas and opinions and openly collaborate with top management, boosting employee morale and engagement and fostering an inclusive and positive work culture, allowing the emergence of new ideas that are of the utmost importance for the company performance, productivity, and ultimately the prosperity of the firm.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study, as any empirical work, comes along with several limitations which represent avenues for future research.

The first limitation was that of small sample size, a limitation that can prevent a clear and generalized statement about our results. The number of participants was too small to adequately generalize beyond the context of this study. With a larger sample, including a greater number of culturally different participants, the results would certainly be more robust and clarifying. Second, employees with managerial responsibilities did not take part in this study; therefore, it becomes important for future studies to include them to provide a more complete approach on this topic. Third, employees who participated in this study were all working in small and medium-sized enterprises based in Portugal, which could lead to a cultural bias and therefore limit the generalizability of the findings. Thus, it would be pertinent to replicate this study in different geographical locations, countries, and socioeconomic contexts. Fourth, in this study employee silence has been regarded as a broad and unitary construct, used for exploratory explanation. Future research should also explore and assess which dimension of employee silence (i.e., acquiescent silence, defensive silence, or pro-social) is more commonly adopted by employees of family firms. This would offer important insights on the characterization of employee silence in family firms and on its association with other relevant organizational variables.

Finally, future research should also consider using the company type (i.e., family vs. non-family) as well as other family-related variables such as family ownership, family participation, and influence in the top management team or the generational stage of the firm as moderators when assessing the relationship and impact of the levels of employee silence in the employee’s perceptions of entrepreneurial orientation. By doing this, future studies could provide a better understanding of the differences between the two contexts.

References

Alayo, M., Maseda, A., Iturralde, T., & Arzubiaga, U. (2019). Internationalization and entrepreneurial orientation of family SMEs: the influence of the family character. International Business Review, 28(1), 48-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.06.003

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

Aparicio, G., Ramos, E., Casillas, J. C., & Iturralde, T. (2021). Family Business Research in the last decade. A bibliometric review. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12503

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gómez-Mejía, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511435355

Boling, J. R., Pieper, T. M., & Covin, J. G. (2016). CEO tenure and entrepreneurial orientation within family and nonfamily firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(4), 891-913. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12150

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267-283. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Chou, S. Y., & Chang, T. (2020). Employee silence and silence antecedents: a theoretical classification. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(3), 401–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417703301

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107

Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677-702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00432.x

Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2019). Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: some suggested guidelines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718773181

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Discua Cruz, A., Howorth, C., & Hamilton, E. (2013). Intrafamily entrepreneurship: the formation and membership of family entrepreneurial teams. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(1), 17-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00534.x

Duran, P., Kammerlander, N., Van Essen, M., & Zellweger, T. (2016). Doing more with less: innovation input and output in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1224-1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0424

Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Sarathy, R. (2008). Resource configuration in family firms: linking resources, strategic planning and technological opportunities to performance. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 26-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00717.x

Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419-1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386

Garcés-Galdeano, L., Larraza-Kintana, M., García-Olaverri, C., & Makri, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: the moderating role of technological intensity and performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(1), 27-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0335-2

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gómez‐Mejía, L. R., Larraza‐Kintana, M., Moyano‐Fuentes, J., & Firfiray, S. (2018). Managerial family ties and employee risk bearing in family firms: evidence from Spanish car dealers. Human Resource Management, 57(5), 993-1007. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21829

Hernández-Linares, R., & López-Fernández, M. C. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation and the family firm: mapping the field and tracing a path for future research. Family Business Review, 31(3), 318-351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518781940

Hernández-Perlines, F., Covin, J. G., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. E. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation, concern for socioemotional wealth preservation, and family firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 126, 197-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.050

Josefy, M. A., Harrison, J. S., Sirmon, D. G., & Carnes, C. (2017). Living and dying: synthesizing the literature on firm survival and failure across stages of development. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 770-799. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0148

Kachaner, N., Stalk, G., & Bloch, A. (2012). What you can learn from family business. Harvard Business Review, 90(11), 102–106.

Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, K. A., & Zellweger, T. M. (2012). Extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: a look at the dark side. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1175-1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00544.x

Kidwell, R. E. (2008). Adelphia Communications: the public company that became a private piggy bank: a case of fraud in the Rigas family firm. In S. Matulich & D. Currie (Eds.), Handbook of frauds, scams, and swindles: Failures of ethics in leadership (pp. 191-205). New York: Taylor and Francis Group.

Kidwell, L. A., & Kidwell, R. E. (2010). Fraud in the family: how family firm characteristics can shape illegal behavior. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association.

Kizildag, D. (2013). Silence of female family members in family firms. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(10), 108-117.

Knoll, M., & Redman, T. (2016). Does the presence of voice imply the absence of silence? the necessity to consider employees’ affective attachment and job engagement. Human Resource Management, 55(5), 829-844. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21744

Kraus, S., Rigtering, J. C., Hughes, M., & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: a quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 161-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-011-0062-9

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 429-451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770-791. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

Miller, D., & Le Breton–Miller, I. (2011). Governance, social identity, and entrepreneurial orientation in closely held public companies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 1051-1076. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00447.x

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: an empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00718.x

Morgan, K. E. (2017). Introducing the employee into employee silence: a reconceptualisation of employee silence from the perspective of those with mental health issues within the workplace. Retrieved from http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/17993/1/Kate%20Morgan%20PhD.pdf. Accessed June 2021.

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706-725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00082.x

Nieto, M. J., Santamaria, L., & Fernandez, Z. (2015). Understanding the innovation behavior of family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 382-399. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12075

Perlow, L., & Williams, S. (2003). Is silence killing your company? IEEE Engineering Management Review, 31(4), 18-23.

Pimentel, D. N. G. (2016). A family matter? Business profile decision and entrepreneurship in family business: the case of the Azores. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade dos Açores (Portugal).

Pimentel, D. (2018). Non-family employees: levels of job satisfaction and organizational justice in small and medium-sized family and non-family firms. European Journal of Family Business, 8(2), 93-102. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v8i2.5178

Pimentel, D., Almeida, P., Marques-Quinteiro, P., & Sousa, M. (2021). Employer branding and psychological contract in family and non-family firms. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 19(3/4), 213-230. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-10-2020-1106

Pimentel, D., Couto, J. P., & Scholten, M. (2017a). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: looking at a European outermost region. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 25(4), 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495817500169

Pimentel, D., Pires, J. S., & Almeida, P. L. (2020). Perceptions of organizational justice and commitment of non-family employees in family and non-family firms. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 23(2), 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-07-2019-0082

Pimentel, D., Scholten, M., & Couto, J. P. (2017b). Profiling family firms in the autonomous region of the Azores. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 46, 91-107.

Pimentel, D., Scholten, M., & Couto, J. P. (2018). Fast or slow? Decision-making styles in small family and nonfamily firms. Journal of Family Business Management, 8(2), 113-125. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-02-2017-0007

Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 20, 331-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(01)20007-3

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Portuguese Association of Family Business (2021). Brochura de Apresentação Empresas Familiares. https://empresasfamiliares.pt/apresentacao-da-associacao-das-empresas-familiares/. Retrieved from Accessed on May 2021.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: an assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761-787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

Sabino, A., & Cesário, F. (2019). O silêncio dos colaboradores de Van Dyne, Ang e Botero (2003): estudo da validade fatorial e da invariância da medida para Portugal. Análise Psicológica, 37(4), 553-564. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1641

Samsami, M., & Schøtt, T. (2021). Family and non-family businesses in Iran: coupling among innovation, internationalization and growth-expectation. European Journal of Family Business, 11(2), 40-55. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10444

Schilling, J., & Kluge, A. (2009). Barriers to organizational learning: an integration of theory and research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(3), 337-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00242.x

Short, J. C., Moss, T. W., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2009). Research in social entrepreneurship: past contributions and future opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(2), 161-194. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.69

Soomro, B. A., & Shah, N. (2019). Determining the impact of entrepreneurial orientation and organizational culture on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee’s performance. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(3), 266-282. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-12-2018-0142

Soriano, D. R., & Huarng, K. H. (2013). Innovation and entrepreneurship in knowledge industries. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1964-1969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.019

Spector, P. E. (2019). Do not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359-1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00384

Wales, W. J., Covin, J. G., & Monsen, E. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation: the necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 14(4), 639-660. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1344

Wang, C. C., Hsieh, H. H., & Wang, Y. D. (2020). Abusive supervision and employee engagement and satisfaction: the mediating role of employee silence. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1845-1858. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2019-0147

Whiteside, D. B., & Barclay, L. J. (2013). Echoes of silence: employee silence as a mediator between overall justice and employee outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(2), 251-266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1467-3

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001

Wilkinson, A., & Fay, C. (2011). New times for employee voice? Human Resource Management, 50(1), 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20411

Zellweger, T. (2007). Time horizon, costs of equity capital, and generic investment strategies of firms. Family Business Review, 20 (1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00080.x