European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 56-63

My Forty Years in Studying and Helping Family Businesses

W. Gibb Dyer

O. Leslie and Dorothy Stone. Professor

Marriott School of Business. Brigham Young University, United States of America

Accepted 2021-05-21

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10, L20, L26

KEYWORDS

Family business, Succession,

Family capital, Family will,

Socio-emotional wealth

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10, L20, L26

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, Sucesión,

Capital familiar, Voluntad familiar, Riqueza

socio-emocional

Abstract This article will describe the trends in the field of family business over the past forty years in terms of theory and practice. Topics such as succession, consulting with family businesses, the effectiveness of family firms, the role of socio-emotional wealth in family firms, heterogeneity in family businesses, and the impact of family capital on the business and the family will be discussed.

Mis cuarenta años estudiando y ayudando a las empresas familiares

Resumen Este artículo describe las tendencias en el campo de la empresa familiar durante los últimos cuarenta años en términos de teoría y práctica. Se discuten temas como la sucesión, la consultoría con las empresas familiares, la eficacia de las empresas familiares, el papel de la riqueza socio-emocional en las empresas familiares, la heterogeneidad en las empresas familiares, y el impacto del capital familiar tanto en la empresa como en la familia.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.12768

Copyright and Licences: European Journal of Family Business (ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X) is an Open Access research e-journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial.

Except where otherwise noted, contents publish on this research e-journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

*Corresponding author

E-mail: w_dyer@byu.edu

1. Introduction

For forty years I have been involved in doing research and consulting with family businesses. My introduction to family business as a subject of study occurred in 1980 during a lunch I had with Dick Beckhard, a faculty member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Dick lived in New York City but would fly to Boston on Thursday nights to teach his Friday class on consulting. I was assigned to be his teaching assistant for this class. During lunch together Dick asked me: “Gibb, what do you know about family businesses?” I admitted that I did not know much, only that my grandfather ran a family-owned grocery store in Portland, Oregon and that my father delivered groceries for him. Dick told me that many of his clients owned and operated family businesses and that they were extremely difficult clients to work with. He would help his clients solve various business problems only to have family conflicts undermine his work. He proposed that we work together on a research project to study the problems of family businesses and suggested that we invite some of his clients to Boston to listen to their issues and concerns. We would then develop a research agenda based on their issues.

After Dick’s family business clients arrived in Boston (there was one client from Canada, two from the U.S. and two from Venezuela), I spent three days listening to problems that I never encountered in my MBA program, which focused primarily on challenges facing large, public corporations. For example, the founder of one family firm said the following:

Succession planning... is really digging your own grave. It’s preparing for your own death and it’s very difficult to make contact with the concept of death emotionally... It is a kind of seppuku—the hara-kiri that Japanese commit. [It’s like] putting a dagger to your belly... and having someone behind you cut off your head... That analogy sounds dramatic, but emotionally it’s close to it. You’re ripping yourself apart—your power, your significance, your leadership, your father role (Dyer, 1992, p. 172).

This statement left an impression on me and I decided that I would focus on the dynamics of family businesses for my dissertation. That is how I got introduced to the field of family business.

In this article I will briefly describe the different trends I have seen regarding theory and practice concerning family firms over the past 40 years. I will briefly review the topics of succession, consulting, family firm performance, socio-emotional wealth and heterogeneity in family firms that have influenced my thinking over the past forty years. I will then present my current focus on family business, that of “family capital.”

2. Succession in the Family Firm

During the meeting in Boston with Dick Beckhard’s clients, the issue of succession in the family business was central to those who participated. Questions that were raised in the meeting included:

1) How can we get the founder of the family business to give up control and start succession planning?

2) How do we prepare the next generation to take over ownership and management of the business?

3) How do we manage conflicts between and within generations of the family business?

As we grappled with these issues, I decided to do my dissertation in a relatively large family business, The Raymond Corporation, that was located in Greene, New York. The company was sixty years old and had gone through a transition from the founder, George Raymond, Sr., to his son, George Raymond, Jr. The next generation of Raymonds were looking to eventually take over the business. As I did an historical study and looked at the transition in family leadership, it was clear the culture of the Raymond family was an important factor (Dyer, 1986). In short, I discovered that a family firm with a “participative” business culture, governed by an “advisory” board of directors, and owned by a “collaborative” family had the best chance for managing succession successfully. There was little research done on family business at the time, but my dissertation and the work of John Ward, Ivan Lansberg, John Davis and others focused largely on the problem of succession. Over time, as a field, we have come to better understand the challenges family firms have in planning for succession and have come up with a variety of good options for family businesses in making such a transition (see Hilburt-Davis & Dyer, 2003). In my early article with Professor Beckhard titled: Managing continuity in the family-owned business we outlined our own views about how to best handle the succession problem (Beckhard & Dyer, 1983).

3. Consulting with Family Businesses

As I started my career as a professor in the Marriott School of Business at Brigham Young University, I had many opportunities to consult with the leaders of family firms. One family business leader I worked with had a particularly difficult problem. He called me and asked me to come to lunch with him where he would then share his concerns. At lunch he said: “Professor Dyer, this is my problem. I thought one of my sons who works for me was doing something unethical, so I fired him. My wife got so angry that she kicked me out of the house and I am sleeping on the couch at my office. What should I do?” This was indeed a difficult problem and over time, in working with the family, I got the father and son to reconcile and come up with a new employment agreement.

This case and others like it encouraged me to try to help family businesses be more effective through effective consulting and I collaborated with Jane Hilburt-Davis in writing one of the first books on the consulting process in family firms that was titled: Consulting to family businesses: A practical guide to contracting, assessment and implementation (Hilburt-Davis & Dyer, 2003). In the book, we describe our approach to helping family businesses by first creating an effective consulting contract with clients so they and ourselves, as consultants, would be clear about the objectives and methodology of the consulting engagement. Second, we outline, using the “three system family business model” that included: 1) the business system, 2) the governance system, and 3) the family system, as a framework for gathering data from the family business and identifying key problems. Third, we describe various interventions that we have used to help family businesses improve. Such interventions include:

1) Family business retreats to help family businesses.

2) Educating the next generation to plan for succession.

3) Creating an effective board of directors for the business.

4) Helping family members work through conflicts.

5) Team building in the family firm.

The last topic, that of team building, is my area of expertise. One of the most important interventions that I have done in family firms is to help family members clarify roles and expectations through a variety of team building exercises. These exercises can be found in my new book, Beyond team building: How to build high-performing teams and the culture to support them (Dyer & Dyer, 2020). Over the years, many more approaches have been developed to help family firms which have been effective in helping family firm leaders deal with the challenges they face.

4. Are Family Firms Really Better?

One of the questions for research early in the formation of the field of family business was: are family businesses more effective than nonfamily firms? The advice at that time by some academics and practitioners was to move the business as quickly as possible away from having family management and to turn to professional managers to operate the business. The transition to professional management would thus avoid nepotism and the family conflicts that plague family firms. However, in 2003, an article by Anderson and Reeb in the Journal of Finance was to change all that (Anderson & Reeb, 2003). They discovered that large public corporations that were led by families performed better than nonfamily firms. This sent shock waves through the field and spurred many studies looking at the differences between family and nonfamily firms to find out if, and why, family firms were better performers than nonfamily firms. The results of this research were conflicting: some studies showed family firms to be more effective than nonfamily firms while other studies came to the opposite conclusion. As I wrestled with this issue, I came to write the article Examining the family effect on firm performance (Dyer, 2006), which used agency theory and the resource-based view of the firm to describe why certain family businesses might be more effective than others and potentially outperform nonfamily firms. I developed a typology of the “clan,” “professional,” “mom and pop,” and “self-interested” family firms, with the clan family firm being the most effective and the self-interested family firm least effective. According to my typology, clans were significantly more effective because they had significant family assets and low agency costs. Conversely, the self-interested firm had significant family liabilities and high agency costs. In this article I did argue, however, that the professional family firm was likely to be the best option for family firms that wanted to grow since it protected family assets by incurring some of the costs related to professionalization. I have continued to look at this issue over time and believe that family firms, under certain circumstances, can indeed outperform nonfamily firms (Dyer, 2018). Much of my consulting work focuses on helping family firms move to become more professional since they do want to grow.

5. The Role of Socio-Emotional Wealth in Family Firms

In recent years, the work by Luis Gómez-Mejía and his colleagues has focused our attention on the role of “socio-emotional wealth” (SEW) on family business dynamics (see, for example, Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). In short, SEW refers to the noneconomic goals that families have when owning and managing a business. These include: the psychic and social rewards from owning a business, using the business to help family members, and seeing the business as an extension of themselves. In my own work, I have looked at how family businesses tend to be more socially responsible than nonfamily firms (Bingham, Dyer, Smith, & Adams, 2011; Dyer & Whetten, 2006). Our studies have suggested that family businesses who are interested in maintaining their SEW are more attuned to be socially responsible by developing safe products, treating employees fairly, and by supporting their local communities. The reason they are more socially responsible is they see the business as an extension of the family and do not want the family reputation to be blemished by poor actions on the part of the firm. Thus, in studying and consulting with family businesses I have found it important to be aware of the fact that noneconomic goals may be as important, or even more important, to a family business.

6. Heterogeneity in Family Businesses

Another theme in my work has been to encourage those who study family businesses to be aware of the heterogeneity that exists in family firms. Initially, much of the research on family firms assumed that they were somewhat similar. However, my article with Peter Jaskiewicz has discussed the variety that we find in family business, from different family structures, cultures, family dynamics, etc. (Jaskiewicz & Dyer, 2017). Moreover, my article with my son, Justin Dyer, has described how important it is not to neglect the family as a variable in family business research (Dyer & Dyer, 2009). Too often, research and consulting practice focuses only on the business outcomes and not family outcomes. For many families, family outcomes—such as positive family relationships—are even more important than profits from the business. I hope that future research and consulting practice will take family business heterogeneity into account more than they have in the past.

7. Helping Family Firms: The Family Capital Approach

My current focus for both research and consulting is to help families strengthen their “family capital”—the human, social, and financial capital that is needed for both the family and the family business to be successful. This approach is fully described in my recent book, The family edge: How your biggest competitive advantage in business isn’t what you’ve been taught . . . It’s your family (Dyer, 2019). I have focused on helping families develop family capital because creating such resources can be very helpful in both family and business contexts. Before proceeding to describe how to create and maintain family capital, I will describe in more detail what I mean by human, social, and financial family capital. These three types of family capital are also valuable to family members even if they have no desire to start a business, since they can help them in other ways to achieve their individual goals.

7.1. Family human capital

Families create human capital by sharing knowledge with family members and helping them develop skills to be successful in life and in business. Through conversations around the dinner table, summer employment in the family business, or by watching and working with their parents, children come to understand how to create new products, service customers, and make sales. We find that in certain industries such as farming, construction, funeral homes and distilled spirits are known for having tried and true business tactics that are passed down from generation to generation as family knowledge. The oldest known family business, the Kongo Gumi construction company in Japan, was founded in 578 AD and is being managed by 40th generation family members. Such a business would not be able to continue as a family firm without the family transferring knowledge and skills to the next generation and helping each other by their labor.

7.2 Family social capital

Family social capital refers to the bonds between family members and those outside the family—relationships that can be used to obtain the resources needed to help family members achieve their goals. An example of the importance of family social capital on start-up success is part of the early story of Microsoft. Microsoft founder Bill Gates was able to sell his DOS operating system to IBM because his mother sat on the board of a foundation with the Chairman of IBM, John R. Opel, and helped Bill make that connection. As a result of that relationship, Bill Gates was able to convince IBM to bundle Microsoft’s software with its personal computers. Without the help of Bill Gates’ mother, Microsoft might not have been able to gain such a dominant position in the software industry. Thus, helping family members develop social capital is one of the goals that I typically have when I consult with family firms. Creating a board of directors with nonfamily outsiders is often an approach I use to get the family to develop connections with important people who can help them.

7.3 Family financial capital and other assets

Family capital concerns financial capital and other tangible assets controlled by the family. In the case of starting a family business that may include things such as office space in the family home, family vehicles, phones, and computers. For example, Steve Jobs, founder of Apple, benefitted from his parents’ generosity when they allowed him to start his company in their garage. Families also can pool their financial and other resources to help the family business succeed. Sam Walton, the founder of WalMart, was able to launch his business because he had access to the financial resources of his rich father-in-law.

7.4. A model of family capital

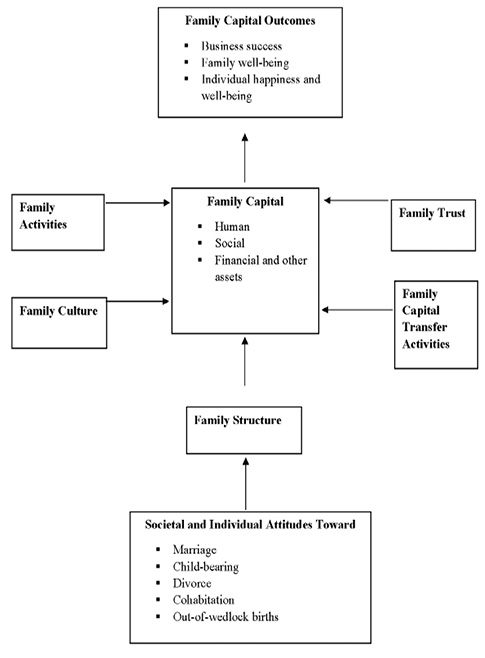

In Figure 1 is the model showing the factors that influence family capital as well as its outcomes. Family structure provides the scaffolding upon which family capital is built and has the most significant impact on family capital. However, other factors in the model such as “family culture,” “family activities,” “family trust,” and “family capital transfer activities” also are important to develop family resources. Finally, the major outcomes of family capital are: 1) business success; 2) family well-being; and 3) individual happiness and well-being. I will discuss each of these factors in turn.

Figure 1. Model of family capital

8. Family Structure

Family structure has a significant impact on family size and stability. In general, marriage supports stable family relationships and birth rates increase family size. Divorce, cohabitation, and single-parenthood tend to have a negative impact of family stability and often family size. In the United States, we are currently facing historic lows in marriage rates and birth rates—which does not bode well for the development of family capital. Moreover, families are more unstable these days due to high divorce and cohabitation rates. European families are in a similar situation compared to U.S. families. If families are not being formed and are not stable, that makes creating and sustaining family businesses more difficult. In other parts of the world, there are different family issues. For example, there are approximately 100 million fewer women than men in Asia—primarily due to selective abortions and female infanticide. Thus, many Asian men will find it difficult, if not impossible, to find mates, get married, and have children, which is clearly detrimental to the formation of family businesses. At its current birth rate, the Japanese will disappear from the earth by the year 2500. This is true in many other countries as well (e.g. Korea, Singapore). The prevalence of HIV/AIDs in Africa has left many African children orphans who will grow up without parental guidance and support. For example, in Swaziland, about one-fifth of all children are orphaned, primarily due to HIV/AIDs which afflicts 31% of Swazis (Dyer, 2019).

In summary, in today’s world, families are fewer in number and are less stable, and that trend is likely to continue in the future. While I am not a family therapist, one of the roles I play as a family business consultant is to help families members get into counseling to help strengthen their families and help couples remain together in harmonious relationships if possible.

9. Family Culture

As I learned from my dissertation research, the culture of one’s family has an impact on family capital since it defines the rules for how family members relate to one another and their environment. “Family culture” can be defined as socially acquired and share rules of conduct that are manifested in a family’s artifacts, perspectives, values, and assumptions (Dyer, 1986).

Artifacts are the overt manifestations of family rules. There are physical artifacts: one’s dress, the state of the rooms in home, implements used for work or school, etc.; verbal artifacts: the language and stories shared by a family; and behavioral artifacts: the rituals and common behavior patterns used by a family. Artifacts are the tangible aspects of culture—things that we can hear, see, or touch.

Cultural perspectives are situation-specific rules of conduct followed by family members. For example, in a specific situation like greeting someone in Japan the appropriate behavior is to bow. Before the pandemic, in the United States and most of the Western world we shake hands. In the context of a family, perspectives are the situation-specific rules for dealing with things like greeting family members, deciding rules like curfews, or showing physical affection in public.

Cultural values are more general, trans-situational rules that are reflected in cultural perspectives and artifacts. For example, some homes have general rules like “respect for one’s elders,” “be honest in all our dealings,” and “hard work is expected.” These values may even be shared in family mission or values statements.

Assumptions are the most fundamental aspects of culture. They are the basic beliefs that underlie the artifacts, perspectives, and values of the family. Some of these assumptions include: our beliefs about whether we can trust other people (both in and outside the family), our beliefs about which family members should make decisions for the family, family beliefs about how family members should be treated and supported, and family beliefs about the family’s ability to change and improve. These assumptions are the basic premises, often unspoken and generally invisible, that “account for” the more overt aspects of culture. I find that families who create strong family capital have a culture based on the following assumptions: 1) we trust one another, 2) over time children should move from a dependent relationship with parents to an interdependent one, 3) the family should be proactive in trying to adapt to and change its environment for the betterment of family members, and 4) the family should help family members reach their full potential. However, I have found that families that have assumptions that reflect distrust, exploitation or abuse of family members, controlling leadership, with an unwillingness to change to improve the family have difficulty developing and sustaining family capital.

10. Family Activities

Families can also strengthen their family capital through the following activities:

1) Family identity activities: these activities include having the family develop a family mission statement or value statement,

2) Family rituals and traditions: these include family vacations, family dinners, family religious traditions, family parties, and other activities that demonstrate that it is important to be a member of the family,

3) Demonstrating commitment to family: Commitment to family general revolves around spending time with family members and demonstrating through actions that family members have priority over other activities,

4) Coping with crises: All families face crises, but those families who rally around each other and support one another during challenging times strengthen their commitment to the family, and

5) “Spiritual wellness.” One final characteristic of families that develop family capital is what Stinnett and DeFrain (1985) call “spiritual wellness,” which means the family is engaged in achieving a purpose that transcends the fact that family members are living together as a biological or economic unit. It means that the family is willing to have a higher purpose as a family that brings them together which often revolves around serving other people.

11. Family Trust

Creating trust in one’s family is also essential to building family capital. There are three types of trust that we typically find in families. These are:

Interpersonal trust—Interpersonal trust is based on one’s relationship with another person and is primarily based on one’s history with that person. To the extent that another person has proven to be predictable and behaves reliably in certain situations, they are deemed to be trustworthy.

Competence trust—Competence trust is based on the skills, abilities, and experience of the other party. If we believe the other person has the necessary expertise to help us, we “trust” his or her judgment and advice. One’s status in the family, academic degrees, certifications, reputation, etc. are often the way we “know” that someone can be trusted.

Institutional Trust—Institutional trust is based on whether we see “the family,” “the system,” “the rules,” or “the processes” as being fair and trustworthy. Family members want to know if they will have a place to stay, food to eat, and receive social support. They also want to know if they can air their grievances and be treated fairly by family members.

My role as a consultant to families who want to strengthen family capital often involves repairing these three types of trust. To repair interpersonal trust, I often serve as a mediator between family members. To improve competence trust I work with family members to develop career goals to gain the skills and education they need to help the family business grow. I also help the family set up guidelines to monitor the performance of family members in the business to ensure that they are competent to perform their assigned work. For institutional trust, I help the family develop mechanisms to share responsibility in decision-making and to be more transparent regarding the family’s dealings—particularly the family leader’s will and succession plan.

12. Family Capital Transfer Activities

The final factor in the family capital model concerns family capital transfer activities. If families do not create processes to transfer family capital to the next generation it may be lost or severely compromised. To help a family transfer family capital, I ask the family to answer the following three questions:

1) What kinds of family capital (human, social, financial) will be helpful to future generations of family members?

2) What family capital do we currently have that should be transferred to the next generation of family members?

3) Who has access to this family capital, or, if we do not have the family capital that is needed, how do we develop it so it can benefit future generations?

My own experience as a consultant and my review of the literature on succession planning suggests that most company founders (and their families) cannot fully answer these questions and are not prepared for succession. Thus, to facilitate the process of transferring family capital, I have found it useful for families to do the following:

1) Create a genogram of one’s nuclear and extended family, and

2) Develop a “family capital genogram” that identifies who in the family has needed family capital,

3) Develop a plan to improve relationships between those who have family capital and those who need it, and

4) Develop specific plans to transfer family capital from one person to another typically by using a “learning by doing” approach. The “learning by doing” approach involves giving potential heirs experiences and holding them accountable to help them prepare for future responsibilities and to develop the skills, knowledge, and relationships needed to carry on the family legacy.

13. The Outcomes of Family Capital

At the top of the model in Figure 1 are listed the outcomes of family capital. Research shows that family capital has many positive benefits for a family and for society at large. In a recent study my research team used data from over 8,000 teenagers to measure their access to family capital and whether that access influenced them to start businesses later in life (Dyer, 2019). The data showed that those youths who had access to family capital: 1) started more businesses, 2) their businesses had greater longevity, and 3) their businesses had significantly higher profits, than those youths who had less family capital. Furthermore, I have found that families who have family capital experience the following benefits:

• Family members are more resilient in dealing with life’s challenges.

• They have a greater sense of well-being, security, and happiness.

• They are more likely to be in healthy and stable family relationships.

• Parents see better school performance and fewer behavioral problems in their children.

These are the important benefits of family capital. Family capital helps families deal more effectively with the challenges that life brings, and for those families who start businesses, family capital helps their businesses succeed in the present and in the future.

In my book, The family edge, I have several surveys that I have developed that can be used to assess a family’s current status regarding family capital and determine if the family’s culture, activities, trust, and family capital transfer activities are sufficient to help the family and its business be successful over time. In summary, my objectives in working with families to strengthen their family capital include:

1) Creating a strong and stable partnership between spouses or significant others.

2) Encouraging a family culture that is based on trust, facilitates the personal growth of family members, and supports positive change within the family.

3) Encouraging family activities that create unity and support within a family. Thus, family mission statements, family traditions, and spending time together as a family is important along with creating a higher purpose for the family.

4) Building trust within the family by repairing interpersonal trust when it is broken. Developing competence trust by encouraging family members to develop skills and abilities and creating institutional trust within the family by sharing decision-making and being transparent.

5) Transferring family capital by identifying where human, social, financial capital and other assets reside within the family. The family should develop a succession plan to ensure that these forms of family capital are transferred to the next generation.

14. Conclusion

In this article I have given a brief overview of my journey in studying and helping family businesses. Family business face a plethora of important issues in today’s world that need to be addressed for the family and the business to succeed over time. Hopefully, the description of my journey will be helpful to you as you chart your own course to studying and helping family businesses.

References

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301-1328. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00567

Beckhard, R., & Dyer, W. G., Jr. (1983). Managing continuity in the family-owned business. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(83)90022-0

Bingham, J. B., Dyer, W. G., Smith, I., & Adams, G. L. (2011). A stakeholder identity orientation approach to corporate social performance in family firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(4), 265-285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0669-9

Dyer, W. G. (1986). Cultural change in family firms: Anticipating and managing business and family transitions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dyer, W. G. (1992). The entrepreneurial experience: Confronting career dilemmas of the start-up executive. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dyer, W. G. (2018). Are family firms really better? Reexamining “Examining the ‘family effect’ on performance”. Family Business Review, 31(2), 240-248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518776516

Dyer, W. G. (2019). The family edge: How your biggest competitive advantage in business isn’t what you’ve been taught—it’s your family. Sanger, CA: Familius.

Dyer, W. G., Jr. (2006). Examining the “family effect” on firm performance. Family Business Review, 19(4), 253-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00074.x

Dyer, W. G., & Dyer, J. H. (2020). Beyond team building: How to build high-performing teams and the culture to support them. New York: Wiley.

Dyer, W. G., Jr., & Dyer, W. J. (2009). Putting the family into family business research. Family Business Review, 22(3), 216-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486509333042

Dyer, W. G., Jr., & Whetten, D. A. (2006). Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S&P 500. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 30(6), 785-802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00151.x

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Hilburt-Davis, J., & Dyer, W. G. (2003). Consulting to family businesses: Contracting, assessment, and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Jaskiewicz, P., & Dyer, W. G. (2017). Addressing the elephant in the room: Disentangling heterogeneity to advance family business research. Family Business Review, 30(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486517700469

Stinnett, N., & DeFrain, J. (1985). The secrets of strong families. Boston: Little, Brown.