European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 6-11

Coexistence, Unity, Professionalism and Prudence

Miguel Ángel Gallo

Emeritus Professor, Strategic Management Department, IESE Business School, Barcelona, Spain

Received 2021-02-16; accepted 2021-03-23

JEL CLASSIFICATION

L20, L21, M10, G30

KEYWORDS

Family firm, Professionalism, Leadership, Coexistence, Family-business balance

CÓDIGOS JEL

L20, L21, M10, G30

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, Profesionalidad, Liderazgo, Convivencia, Equilibrio

empresa-familia

Abstract Family firms are complex and dynamic entities that are rich with peculiar, idiosyncratic features. The objective of this paper is to provide guidance to help those involved in family businesses, businesspersons, and family members to pursue the continuity of the family firm over time. Based on the author’s experience with entrepreneurs who built successful businesses, this paper identifies four elements that are critical to achieve transgenerational continuity in family firms, namely: coexistence, unity, professionalism, and prudence. The analysis of each element provides suggestions and key considerations for both scholars and practitioners in the family business field.

Convivencia, unidad, profesionalidad y prudencia

Resumen Las empresas familiares son entidades complejas y dinámicas, así como ricas en características peculiares e idiosincrásicas. El objetivo de este documento es brindar orientación para ayudar a quienes participan en empresas familiares, empresarios y familiares para buscar la continuidad de la empresa familiar en el tiempo. En base a la experiencia del autor con emprendedores que construyeron negocios exitosos, este trabajo identifica cuatro elementos que son críticos para lograr la continuidad transgeneracional en las empresas familiares: convivencia, unidad, profesionalidad y prudencia. El análisis de cada elemento proporciona sugerencias y consideraciones clave tanto para académicos como para profesionales del campo de la empresa familiar.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.11973

Copyright and Licences: European Journal of Family Business (ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X) is an Open Access research e-journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial.

Except where otherwise noted, contents publish on this research e-journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

*Corresponding author

E-mail: mgallo@iese.edu

1. Introduction

A long time has passed since the publication of Gallo and Sveen’s (1991) article in the Family Business Review journal. I have had the opportunity to meet a significant number of family businesses in different countries during this time. On many occasions, I have also had the opportunity to contribute to their development and growth by performing the responsibilities of a member of their ordinary governing body, the Board of Directors.

Building a good firm is always an arduous task but leading a family business with the intention of ensuring its continuity over several generations is a particularly difficult example.

In the following brief notes, I shall try to share part of what I have learned from family entrepreneurs who have succeeded. Entrepreneurs who are true masters of coexistence, unity, professionalism, and prudence.

2. Learning from Entrepreneurs who Successfully Built Good Family Businesses

The entrepreneurs who successfully build good family businesses are undoubtedly masters of COEXISTENCE. Coexistence is that between family members who work in the firm, with the rest of its employees, and with the other family members. The fact that successful coexistence must take place for long periods of time should not be forgotten. With the general increase in life expectancy, nowadays, it is not rare to find three generations working in a firm, thus the periods of coexistence can last a significant number of years.

A significant number of academics have devoted and continue to devote their efforts to research succession in family businesses (e.g., Beckhard & Dyer, 1983; Cabrera-Suárez, De Saa-Pérez, & García-Almeida, 2001; Corrales-Villegas, Ochoa-Jiménez, & Jacobo-Hernández, 2018; Daspit, Holt, Chrisman, & Long, 2016; Gallo, 1998). Generally, such research does not consider, as would be appropriate, that succession is a process that occurs within a period of good or bad coexistence. If the coexistence has been and continues to be good, the succession is more likely to be successful. However, when the coexistence is not good, the succession is often traumatic. The study of succession should therefore include the analysis of coexistence.

Following Álvaro D’Ors (cited in Domingo, 1987), the important distinction between ‘potestas’ as socially recognised ‘force’, that is, ‘power’, and ‘auctoritas’ as socially recognised ‘truth’, that is, recognised ‘knowledge’, is considered on several occasions. This distinction is crucial to better understand many of the firm’s governance problems, especially in the case of family businesses.

The balance between these two different realities in individuals, between their personal levels of ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’, is necessary for them to successfully carry out their responsibilities in the firm. The exercise of a broad ‘potestas’, which is generally linked to ownership, by those who have a low level of ‘auctoritas’ leads to tyranny, and a good coexistence is not possible in such cases. On the other hand, considering that the opposite situation can occur, whereby the level of ‘potestas’ is much lower than that of ‘auctoritas’ for a more or less prolonged period of time, is equivalent to thinking of the actuality of a coexistence that will never be real.

Both situations of imbalance are often resolved rather quickly in non-family businesses. The opportunities provided by the capital market (capital with which the ‘potestas’ is acquired) and the professional market (individuals with knowledge and qualities that allow them to possess a recognised ‘auctoritas’) influence the solution to such problems, since they make it possible to achieve a new balance soon compared to family businesses. However, this tends not to be the case in family businesses in which the two ‘markets’ often operate very differently. This is because there is no capital market or a very small one, so the change of ownership occurs late or not at all, and the ‘potestas’ therefore remains unchanged. Furthermore, the professional market is not generally as influenced by competitive forces as in the case of non-family businesses. Hence, the imbalance can last much longer unless action is taken, which often tends to be drastic, or painful events occur, such as traumatic separation or the death of a family member.

Ensuring a successful coexistence is one of the main responsibilities of those who have ‘potestas’ in the firm. If they do not know how to or do not want to promote and achieve it, they will show a serious deficit in their level of ‘auctoritas’.

Coexistence is about living with others, establishing a ‘community of some principles of thinking, feeling, and willing’ (Ortega y Gasset, 1984, p. 47) in interpersonal relationships. Establishing this community of principles is everyone’s responsibility, but especially those in power. As members of an extended family pursuing the project of continuity, others also have their share of responsibility, even if they are not part of the family business.

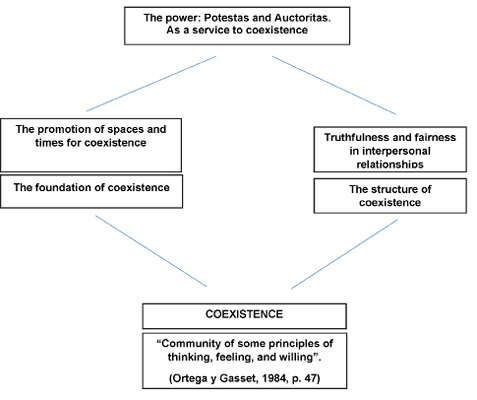

Those who hold power in family businesses, now understood as both ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’, should place it at the service of coexistence. They should bear in mind that the seed of coexistence can only arise and develop firstly by promoting spaces and times in which individuals can live together in harmony, and secondly, that the interpersonal relationships that exist in these spaces and times should be based on truthfulness and fairness. According to these considerations, Figure 1 graphically illustrates coexistence building.

Figure 1. Coexistence building

Building and maintaining a successful coexistence over a long period of time is a difficult challenge. The spaces and times for coexistence have to be pleasant, and this depends on almost all of those who live together. Truthfulness and fairness also depend on each person who lives together. However, if the coexistence disappears, it is preferable to find new and different ways out of the family business, since the intended project can no longer be carried out as planned. There will be no unity if people are not able to coexist harmoniously, and what is not united runs the risk of deteriorating. What is not united sooner or later deteriorates. This leads to another of the basic requirements for achieving continuity.

As is well known, family members’ unity with each other and with their firm is the fundamental strength of the family business. It is fundamental in the sense that the strengths of the firm can be built on this basis to compete in the environment. A lack of unity is a shaky ground on which no lasting competitive strength can be built, but rather ground for significant weaknesses to emerge when competing.

Since the passage of time can promote its erosion as family members evolve and their preferences and intentions change, achieving the necessary level of unity and keeping it alive requires a significant and growing input of energy.

This energy in family businesses is the double COMMITMENT of all involved. Firstly, commitment to govern, manage, and run the firm with the professionalism of any good businessperson. Secondly, commitment not to fall into the well-known ‘traps’ that are so typical of family businesses. Since it is very difficult to avoid falling into these traps over long periods of time, commitment to implement an effective and lasting way out of such traps before disunity occurs.

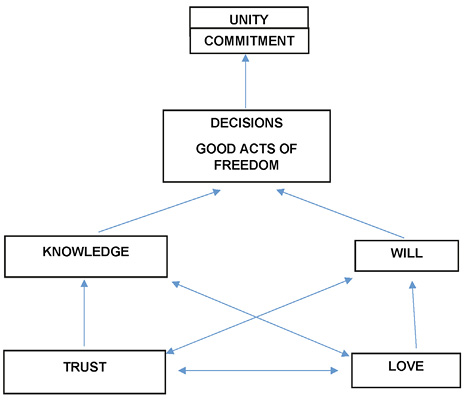

The most common way for family members to bring energy for unity, that is, to fulfil their commitment to the firm, is by making and implementing free decisions when carrying out their individual responsibilities. In other words, the decisions that correspond to the ‘potestas’ that they have in the firm.

For a decision to be free, one must have knowledge of what is being decided. Furthermore, one must have the will to decide, that is, to abide by the consequences that follow the making and implementation of the decision. In other words, one must decide based on the appropriate level of ‘auctoritas’.

As expected, further reflection on commitment in family businesses brings us back to the necessary balance that each family member needs to achieve between their levels of ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’ so as not to neglect them.

When carrying out responsibilities in the firm, it is nearly impossible to have all the necessary knowledge to make decisions if one does not trust others. The acquisition of knowledge in the firm implies trusting others’ information and intentions. In addition, the willingness to decide freely in a family business presupposes the love for the business project. Based on these statements, Figure 2 graphically illustrates the structure with unity at the top and the commitment with the energy that keeps it solid.

Figure 2. Unity-commitment building

Knowledge, gained through one’s own effort and supported by trust, and will, the operationalisation of love for the project, are closely linked. When well united, they give rise to the positive virtuous spiral of ‘knowing more to love more’, and, consequently, to the decision in favour of professionalism in the work of all. When poorly united, they give rise to the negative vicious spiral of ‘losing love and knowledge due to increasing distrust’, and, consequently, the decision in favour of personal instead of common good.

This leads to the third point that is essential for continuity over several generations, PROFESSIONALISM. It is appropriate to start with a statement that family members sometimes need to be strongly reminded of, whether or not they are part of the family business, as well as some of those who advise in the field of family business: to be a good family business, it is necessary, first and foremost, to be a good business firm.

There are few doubts regarding which comes first, ‘to be a good family and then build a good business firm’ or, conversely, ‘to be a good business firm and strive to be a good family firm’. In almost all cases, one must first have a good business firm. To do business honestly in a competitive environment is an arduous task, and requires permanent professionalism, since possible temporary strokes of genius are not sufficient. The affirmation of the need for professionalism does not imply that family members should be removed from the business. On the contrary, it is an urgent call for them to acquire the necessary qualities to carry out responsibilities in their businesses, something that is not impossible, and that has an ethically required minimum, acquiring the skills that will make them a responsible owner.

Unless it is a form of apprenticeship, giving responsibilities to those who are not professionally prepared, that is, who do not have the ‘auctoritas’ required to carry them out, is a serious mistake that the firm and the individuals end up paying for. It is also a mistake to create new jobs or duplicate existing ones to give ‘shelter’ to family members who do not have or do not want to have other alternatives.

The firm’s responsibility structure, that is, its set of jobs, should be the vehicle through which the company fulfils its strategy. Each job should provide the best possible balance between ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’ in the person who performs it.

The preparation of the family business so that coexistence, unity, and the balance between ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’ becomes a reality, and that this reality continues to be present even when people change and environments evolve, requires the exercise of the habit of PRUDENCE as a ‘rational, true, and practical disposition with regard to what is good… and an inherent quality of politicians and administrators’ (Aristotle, p. 93). That is, it is the main virtue of the good ruler.

The increase in complexity of most family businesses is inherent to the development and growth of the business and the family (Gersick et al., 1997; Gómez & Gallo, 2015). A prudent firm’s governance also consists of preparing to be able to deal with such complexity and achieve continuity from an early stage.

For many years, the firm’s continuity has been considered one of its social responsibilities. Continuity does not mean staying in the same business for decades and even centuries, but it does mean continuity in entrepreneurship, job creation, and investment opportunities.

In accordance with the previous points, those who are crucial to the firm’s governance must ensure that, in the future, the firm’s ownership, governance, and management will be in the hands of those who, knowing and willing to coexist, are drivers of unity, have their levels of ‘auctoritas’ in balance with their levels of ‘potestas’, and are eagerly seeking the continuity of the firm.

Prudence will lead them to discover those family members who wish to share the entire project and those who do not, as well as those who wish to start their own business project and those who wish to stay aside or follow other paths.

For the reasons indicated above, prudence will also prompt them to prepare the firm’s corporate and organisational structure so that the group can be subdivided before there is a disunity that would be difficult to resolve and that would weaken the firm, perhaps irreparably.

When speaking of ‘pruning the tree’, this generally refers to a drastic way of acting during the transition from the first to the second generation in small family businesses, in ‘comparison’ with the family size. This way of acting tends to lead to the disunity of the family, with the firm often becoming no more than a ‘bonsai’.

This loses sight of the fact that ‘pruning the tree’ is often necessary in large, developed family businesses and small-sized families, also in ‘comparison’ with the firm’s size. This new understanding has the ultimate goal of preserving the unity of each business activity and is equivalent to separating dry branches, transplanting, and grafting, so the initial business becomes a collection of different leafy trees.

Prudence will lead to the issue of a ‘plague of ties’ in the exercise of political rights, ties not only in the general meetings of the owners of the firm’s capital, but also in its governing bodies. This is a disease that starts well before the discussion takes place, since the latent threat of a tie vote is well known. This disease is much more widespread in the family business than one might think. This is because it is not openly discussed and is even hidden behind expressions such as ‘it will never happen to us’. This disease is undoubtedly one of the important causes of the slower development of family businesses, as well as their death.

There are known procedures to solve tie votes, since the disease is old but so are the existing remedies. However, they are not clearly established to avoid referring to the scourge of the disease. When they are established, it is not customary to consider that the best action would be to quickly solve the tie, since the competitive environment has its own dynamics, and the firm cannot follow any other.

When structuring the firm’s assets and liabilities, prudence entails how to have the necessary funds to ‘prune the tree’. For many family businesses, these funds have been referred to as ‘macro liquidity’, which should be considered one of the strategic funds for the future.

All of the above is the polar opposite of a type of firm that many external, and not very experienced, observers do not hesitate to describe as a very good family business. A firm that has been in the hands of an excellent businessperson who, with their great strategic vision, did not insist on continuing with mature businesses, but knew how to strategically revitalise the firm and successfully developed its organisation.

Some or all of the owner’s children are part of the firm. The owner has a family protocol that is implemented in matters that do not require a strong commitment, nor a discussion that could lead to discord. Similarly, the firm has its ordinary governing body with directors who, in theory, are independent, but, in reality, are ‘vases’ that adorn the firm, or ‘yes men’ who praise the owner.

Most of those with whom the owner and other members of the firm interact consider the owner to be an excellent businessperson and the firm to be a model family business.

Unfortunately, on many occasions, this is not a model of coexistence, nor of unity since this firm’s unity is only temporary and apparent. It is also not a model of a permanent search for a balance between ‘potestas’ and ‘auctoritas’, and much less an example of prudence. On the contrary, this is a person for whom the firm is a ‘personal toy’. At the core, this leader’s intentions are considering the firm they have designed, built, maintained, and improved as a personal toy. The toy of its owner and master, who is intelligent and wilful, but rather irresponsible for not thinking with due realism about the continuity of the firm when the owner is gone.

This leader is happy with their toy and is determined to play as long as they have the strength. They will play part-time when they lack the strength, not getting tired beyond reason, and will publicly state that the succession has occurred and that this happened successfully. However, the controls of the toy, the ‘potestas’, will remain in their hands, and their ability to set the future route, ‘auctoritas’, will be weak and non-existent.

3. Conclusion

It is not about ending on a pessimistic note, with the theme of the ‘toy’, but it is about encouraging those involved in family businesses, businesspersons, and family members to make the effort to improve the firm’s viability. This is the only way to create quality jobs and non-speculative investment opportunities, two of the scarcest assets in recent years, and whose real improvement will not occur by any other means than having good businesses.

Extensive research on family businesses is still required. However, such research should focus on more fundamental points about how to enable the continuity of this very attractive type of business.

There is much to be done in family business counselling. To some extent, this counselling should also focus more strongly on improving the qualities of the individual.

Businesspersons and their successors have a significant amount of work ahead of them, but this can lead to sterile results if they do not strive to achieve the ‘auctoritas’, which enables the firm to fulfil its social responsibilities. Without this ‘auctoritas’, they do not deserve the ‘potestas’ they have or will get. They will not be happy, and their life will not have been as useful to society as it could and should have been.

References

Aristotle (1999). Ética a Nicómaco (7th edition). Colección Clásicos Políticos. Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, Ministerio de la Presidencia del Gobierno de España.

Beckhard, R., & Dyer, W. G., Jr. (1983). Managing continuity in the family-owned business. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(83)90022-0

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resourceand knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Corrales-Villegas, S. A., Ochoa-Jiménez, S., Jacobo-Hernández, C. A. (2019). Leadership in the family business in relation to the desirable attributes for the successor: Evidence from Mexico. European Journal of Family Business, 8(2), 109-120. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v8i2.5193

Daspit, J., Holt, D., Chrisman, J., & Long, R. (2016). Examining family firm succession from a social exchange perspective: A multiphase, multistakeholder review. Family Business Review, 29(1), 44-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515599688

Domingo, R. (1987). Teoría de la “auctoritas”. EUNSA – Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona.

Gallo, M. A. (1998). La sucesión en la empresa familiar. Servicio de Estudios de la Caixa, Barcelona.

Gallo, M. A., & Sveen, J. (1991). Internationalizing the family business: Facilitating and restraining factors. Family Business Review, 4(2), 181-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1991.00181.x

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, M. C., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA.

Gómez, G., & Gallo, M. A. (2015). Evolución y desarrollo de la empresa y de la familia. EUNSA – Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona.

Ortega y Gasset, J. (1984). Una interpretación de la historia universal (2nd edition). Revista de Occidente en Alianza Editorial, Madrid.