European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 130-143

The Competitive Advantages of Multi-Family Offices over Banks in Serving Wealthy Clients in Poland

Magdalena Kozińska

Banking Institute, Warsaw School of Economics, Warsaw, Poland

JEL CLASSIFICATION

D02, D14, D31, D53, G21, G23, L84

KEYWORDS

Banking sector, Competitive advantages, Services for wealthy clients, Ultra high net worth individuals, Wealth, Multi-family office

CÓDIGOS JEL

D02, D14, D31, D53, G21, G23, L84

PALABRAS CLAVE

Oficina multifamiliar, Particulares con patrimonios muy elevados, Patrimonio, Sector bancario, Servicios para clientes adinerados, Ventajas competitivas

Abstract In Poland, the main players in serving wealthy clients are banks. Nevertheless, the number of multi-family offices (MFOs) has increased notably, raising questions whether they can become real competitors to the private banking divisions. Therefore, an analysis of the activity profile of MFOs and private banking in Poland was conducted. Additionally, a survey of MFOs enabled the evaluation of their perceived competitive positions. The level of development of MFOs in Poland is low and their market is in its infancy. MFOs operating in Poland are, however, considerably more flexible than banks operating in the field of private banking.

Las ventajas competitivas de las family offices multifamiliares frente a los bancos para atender a los clientes adinerados en Polonia

Resumen En Polonia, los principales actores en el servicio a los clientes adinerados son los bancos. Sin embargo, el número de family office multifamiliares (MFOs) ha aumentado notablemente, lo que plantea la cuestión de si pueden convertirse en verdaderos competidores de las divisiones de banca privada. Por ello, en este artículo se analiza el perfil de actividad de las oficinas multifamiliares y de la banca privada en Polonia. Además, una encuesta realizada a las MFOs permitió evaluar su posición competitiva percibida. El nivel de desarrollo de las MFOs en Polonia es bajo y su mercado está en sus inicios. Sin embargo, las MFO que operan en Polonia son considerablemente más flexibles que los bancos que operan en el ámbito de la banca privada.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.11961

Copyright 2021: Magdalena Kozińska

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: e-mail: mkozin@sgh.waw.pl

1. Introduction

The prototype of contemporary family offices can be found in Europe as early as the 6th century, where the majordomo (chief steward) was responsible for the management of the entire court and royal goods (Kammerlander & Schickinger, 2019). Importantly, the majordomo performed the indicated functions only in relation to one family. Later, financial asset management for the wealthiest people in Europe was performed by the emerging private banks, with a bank typically serving more than one family. Nowadays, the growing interest in these entities, whose task is to care for all the assets of the most affluent families, stems from the creation in 1838 in the USA of the House of Morgan, a dedicated entity whose duty was to monitor and manage the assets of the Morgan family (Fernández-Moya & Castro-Balaguer, 2011; Warwick-Ching, 2017). Shortly thereafter, a similar solution was introduced by the Rockefeller family (Dromberg, 2019). Since then, the popularity of family offices has also grown in Europe, and currently in Asia. Among them family offices serving a few rich families at the same time (i.e., multi-family offices - MFOs) seems to be of the particular interest. In this regard, they have become the next type of institutions serving extremely affluent clients competing with traditional financial institutions, especially banks and their private banking offer. Due to the similar profile of activity, it is therefore justified to investigate more the functioning of the MFOs and private banks in terms of their competitive advantages for the customers.

The issue seems to be relevant from the Polish perspective, since the number and incomes of affluent clients rise rapidly (KPMG 2021) and therefore the demand for financial and non-financial services for affluent clients will grow. Moreover, the assets of Polish wealthy families are growing and become more and more complicated in structure. This is at the moment when about 60% of national family enterprises plan the generation transfer (Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Technology, 2019) requiring sophisticated legal and financial services, which in Poland are delivered mainly by private banking departments, MFOs, as well as consulting companies and law firms advertising its “family office offer”.

Moreover, in Poland, MFOs are still extremely new — nearly 78% of them have been created after 2012 — and represent a niche segment of the financial services sector. The number of entities that provide MFO in the strict sense1 in Poland is just seventeen2. However, due to their characteristic business profile — offering an extended range of services, even beyond the financial — they seem to be developing as natural competition3 to banks, the traditional providers of financial services for wealthy families. Banks, via their private banking departments, are also providing a broad scope of services. In the face of soaring demand for services for rich families, it is interesting to evaluate the chances of MFOs – as new type of institutions – to become a real alternative for private banking in Poland.

The aim of this article is to assess whether family offices providing services to many highly affluent families (MFOs) can be a real competition for private banking in Poland in the face of growing demand for the comprehensive care about the entire wealth of the increasing number of affluent families. For this purpose, the functional approach and the scope of activities of family offices are presented — focused on MFOs as representative of the species. Subsequently, the profile of MFOs and credit institutions4 are compared according to four criteria: institutional, product, financial, and operational. This facilitated an examination of the competitive advantages of MFOs over banks. Then, entities belonging to the group of MFOs in Poland were asked to participate in a survey appraising their own positions as competitors to banks in Poland5.

Firstly, this article opens the literature with empirical studies about family offices in Poland. So far, no research has been conducted to investigate the scale of development of these type of institutions in Poland. In this regard, the article also constitutes an important contribution to the literature on the financial institutions in the Polish financial system and the independencies between family offices and other financial institutions. Secondly, the presented research is added value to the broader topic of the financial services for wealthy clients, which is dominated by the private banking and asset management. Moreover, it contributes to the literature stream on the competition between banks and other financial intermediaries in Poland. Important lessons might be drawn not only by MFOs, but also banks.

This article comprises four parts. After profound introduction, the first chapter provides a general description of the activities of MFOs. In the second section, the comparison of the scope of activities of MFOs with private banking departments was included. The third part presents the characteristics of the MFO market segment in comparison with the Polish banking sector — using commonly available data and financial indicators. The fourth section of the article presents the results of the survey in which representatives of MFOs in Poland assessed their competitive advantages as an alternative to the private banking services of the country’s banks. The last part of the article contains the summary of the paper.

2. Boundaries of the Concept of “Multi-Family Office”

The concept of family office was first introduced in 1980 by the sociologist Marvin Dunn, who described it as the entity responsible for managing the finances of wealthy families whose economic power could be diluted due to the passing of assets to successive generations, but the notion of family offices remained unpopular subject of scientific research6.

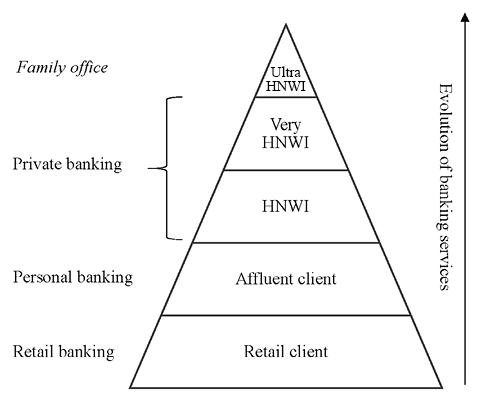

Among various types of family offices, the MFOs could be distinguished as one (beside single family offices) of the most popular notions defining the activity of entities which main aim is the comprehensive service of affluent families. Considering the scope and profile of services provided by family offices (including MFOs), the literature suggests that they constitute the most advanced form of financial services being considered a continuation of the evolution of banking services and independent financial intermediaries (Ventrone, 2005) as depicted graphically in Figure 1. Therefore, it is even more important to evaluate MFOs as the potential competitors of banks.

Figure 1. The family office as a stage of banking services evolution relative to the wealth of its clients.

Source: own work

As indicated, initially entities providing “family office-like” services were earmarked for the service of only one family and are named single family offices (SFO). In this classic form, family offices serve the world’s wealthiest families — e.g., Iconiq Capital handling the assets of Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook; Cascade Investments serves Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft; the Soros Fund Management serving George Soros, a stock market investor; and Kulczyk Investments SA established to manage the assets of the Kulczyk family, one of Poland’s richest. Over time, however, the accumulation of knowledge and skills, as well as the desire to improve the financial efficiency of their resources, led some SFOs to gradually expand their group of clients, which resulted in the formation of MFOs (Ventrone, 2005). In such case, the service of wealthy families often takes the form of the MFO creating a dedicated entity for each family — usually a foundation or trust — which takes control over all family property. The MFO is then responsible for coordinating all the services required to maintain the assets of the family. Regardless of the adopted operational formula — i.e., serving one or more families — the concept of family offices remains unchanged. A comparison of SFOs and MFOs is presented in Appendix 1.

MFOs offer multiple benefits for the clients, e.g.:

• Management of the family’s property is centralized. A single entity handles potentially all the family’s needs; hence, there is no need to engage multiple entities to deliver services.

• Privacy and confidentiality are ensured in family matters due to the limited number of entities with which the family cooperates.

• Service customization provides better alignment with the family’s needs.

• Service is provided by a dedicated team of professionals.

The above-mentioned advantages should, however, be juxtaposed with the potential disadvantages. The first one concerns costs, which are usually higher than in case of private banking due to the higher level of customization. At the same time, the level of individualization of services is not at the highest level, since there are still SFOs that offer it to the greater extent. Moreover, smaller scale activity of MFOs results in a weaker negotiation position than international banks, for example, meaning that they are less able to arrange better deals as regards the products they offer to families.

Types of services provided by MFOs are generally similar in their nature to the ones delivered by the SFOs and could be classified into three groups: investment, administrative, and social (Rivo-López et al., 2017). Sometimes (Tudini, 2005, p. 179) they are divided into two groups:

• Core services classified into four macro categories: investment management, accounting and wealth reporting, tax planning and retirement plans, and trusteeship.

• Additional services: business consulting and corporate finance, charity and philanthropy, family management, and concierge.

Generally, a service that clearly distinguishes family offices from other types of institutions is the preparation of a family constitution — also called a family protocol or family charter (Fernández-Moya & Castro-Balaguer, 2011). As Hartley (2015) points out, the family constitution is a document that defines the rights, values, responsibilities, and rules applicable to family members and businesses, as well as sets out plans and structures that the family should adhere to in its further operations. Typical elements of a family constitution include rules regarding the ownership structure and changes to it — e.g., inheritance, liquidation of property, marriage, and divorce — the obligations and rights of family members — e.g., to remuneration and other benefits — as well as rules of conflict resolution (Deloitte, 2017).

When analyzing the models of MFOs’ activities, note that not all the indicated services are provided directly by these entities. There are family offices that only coordinate the provision of the above-mentioned services on behalf of the wealthy family, but do not provide them directly. This applies in particular to investment advice services regarding financial instruments, which are provided by specialized entities — e.g., asset managers and investment banks (Ventrone, 2005). A similar situation may also apply to, for example, legal advisory services, which may be provided by trusted law firms and not necessarily by the family office itself.

It seems, however, that the range and types of services provided by MFOs do not constitute a key argument in favor of employing them, as similar services can be successfully offered by other specialized financial market entities. It is emphasized that an important factor distinguishing the services of generally family offices is an integrated, coherent approach to family management both in terms of its property and non-property matters, which incorporates a long-term perspective reflecting the phase of the development cycle of the family and its businesses (Ventrone, 2005, p. 139). This statement is naturally true for the MFOs. However, the principal-agent problem is eliminated mainly when establishing SFOs, which are an integrated part of a family, because no one is able to treat problems better than the entity which the problem concerns (Curtis, 2001). Hence, Curtis argues that the best solution to the management of family affairs should be family offices established and operating within a particular family - SFOs. Such solutions are, however, dedicated to ultra-wealthy families — it is assumed that family offices are suitable for clients referred to as Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals (Ultra HNWI) — i.e., people whose liquid assets exceed USD 50 million (Ślązak, 2018). Some sources indicate USD 500 million7 as the minimum threshold of assets necessary to gain access to family office services (Decker-Lange & Lange, 2013).

Considering the level of wealth that is assessed as necessary, it should be noted that some MFOs may provide their (limited scope of) services virtually, what is connected with lower costs and wider potential group of interested families (Russ, 2018). Such family offices are virtual family office (VFO) that operate as internet platforms on which the family can access an ordered overview of its assets. Such solution is offered for families with a minimum value of family assets at USD 25 million. The platform and the accompanying services and expertise can be used by many families simultaneously. However, the main disadvantages are problems with data confidentiality and the continuity of services provided by the online platform (What is a Virtual Family Office?, 2019).

3. Multi-Family Offices vs. Private Banking in Poland — A Comparison of Characteristics

The comparison of the activities of MFOs versus banks serving wealthy clients in Poland8 has been conducted on the basis of four criteria:

• institutional

• financial

• operational

• product

The analysis – conducted in the indicated four dimensions – was summarized in the Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of the business profiles of banks and MFOs.

|

Criterion of comparison |

Banks |

MFOs |

|

Institutional |

Regulated and supervised activity (due to the type of entity). Obligatory reporting to financial safety net institutions. Obligatory publication of financial statements. |

In principle, unregulated and unsupervised activity. No requirement to report to the financial safety net institutions. No duty to publish their financial statements — unless the company is traded on the stock exchange. |

|

Financial |

Specific format of financial statements and the obligation to publish them. High leverage. High share of credit activity in banks’ overall activities. Interest-fee income model. Possible to forecast banks’ financial results. |

Standard format of financial statements and no duty to publish them. Lower leverage. Lower share of credit activity in the MFOs’ overall activities. Income from remuneration for their services to wealthy families (almost a fee-based model). More difficult to forecast financial results due to the high customization of services and client confidentiality. |

|

Operational |

Restricted flexibility in creating the organizational structure of a bank. More formalized structure. |

Full flexibilty in creating the organizational structure of a MFO. Less formalized structure. |

|

Product |

Primarily banking services with the possibility of extension (by bank teams dedicated to wealthy clients). |

A broad range of own services and other financial institutions’ services (agent model). |

3.1. Institutional dimension

Regarding the first criterion, the main difference between MFOs and banks is the regulatory environment in which they operate. The conduct of the business activity of banks in Poland, including those offering private banking services, is limited in terms of the legal form — e.g., a bank cannot be established in the form of a limited liability company — and requires approval — the start of a bank’s activity requires two licenses: to establish the bank and to actually open for business. In addition, banking activity requires compliance with a number of standards, including prudential ones, specifying minimum ratios that a bank must maintain to demonstrate its ability to continue its operations — e.g., regarding liquidity and capital adequacy. However, none of the above-mentioned requirements or restrictions apply to MFOs. They can operate in any legal form, without the need to secure a license or meet any formal requirements. More than three-quarters of MFOs operating in Poland are simple limited liability companies9.

With regard to the institutional environment in which the compared institutions operate, the activities of the banking sector are monitored directly by several institutions (referred to as the financial safety net), which include the country’s central bank, the supervisor the deposit guarantor, the resolution authority, and the Ministry of Finance, and indirectly by rating agencies, analysts, and auditors (Alińska, 2012). However, the financial safety net institutions do not directly engage in controlling the activities of MFOs, except to the extent that any of the activities they engage in are legally required to be supervised. In actuality, there is no supervision of MFOs, and only rarely are the institutions included in the broad safety net interested in the operation of the MFOs. Few of them are rated, and they are also reluctant to use the services of auditors to examine their books. This fact may be due to several factors:

• In comparison with banks, they constitute a much newer form of customer service, so legislation has not yet managed to include them in the group of entities requiring special supervision — like for example, fin-techs.

• MFOs usually constitute a niche of the financial system, the significance of their activities is low; therefore, they are not of interest to regulators.

• MFOs, unlike banks, do not accept funds from their clients for management and do not subject them to risk. They act as intermediaries between wealthy clients and the financial institutions that ultimately invest the funds.

• MFOs manage the affairs (including financial) of very wealthy people who may believe that a potential loss resulting from a lack of professionalism in the entity that serves them will not have such far-reaching consequences as in the case of less wealthy people. Therefore, no form of external control is necessary beyond that exercised by the clients themselves.

3.2. Financial dimension

Banks and MFOs differ significantly in regard to their finances. First, their financial statements are different. Banks prepare financial statements according to a detailed format that is specific to them. The financial statements of MFOs correspond to the classic format, according to which all non-financial enterprises report — other than credit and insurance institutions. Banks are also obliged to publish their financial statements, which is not required of family offices. The structure of their financial statements is also distinct. Banks use high leverage, while MFOs rely less on debt, although the scale of this depends on the MFO and the phase of its operation, as well as its scope of services. In the case of MFOs that offer financial support to their clients’ investments, these funds must be obtained from other institutions, usually in the form of debt. Note, however, that typical family office clients are so-called “depository customers” who are looking for services to organize their assets and manage them. This does not focus on obtaining funding, since this type of client usually has a liquidity surplus. Even if this were the case, the MFO would usually support obtaining such financing from credit institutions. Furthermore, on the active side of the balance sheet of MFOs (as opposed to banks), it will be unlikely to find loans since credits are legally restricted to banks alone and form the core of their assets. The structure of the profit and loss statement is also slightly different. In the case of banks, it is based on interest income and expense as well as fees charged. The receivables collected from the clients of MFOs depend on the adopted remuneration method and constitute the office’s operating income, which can be compared with a bank’s income from fees and commissions. Financial revenues and costs are usually of little importance to MFOs, due to the fact that they are usually not involved in the purchase of financial instruments, as banks often are for speculative or hedging purposes. The involvement of MFOs in the financial markets is usually limited to advising their clients. Therefore, they are not direct participants in those markets, which also means that MFOs are not exposed to fluctuations in the valuation of their assets, and hence their financial results. While the scale of the provided services is potentially lower as compared to banks due to having fewer clients, MFOs depend on the current demand of wealthy families seeking new solutions, with remuneration rates individually negotiated. Hence, the financial results of MFOs are more difficult to forecast by external analysts who generally do not know details of the portfolios of an institution’s clients.

3.3. Operational dimension

In Poland, there are also significant organizational differences between banks and MFOs. First of all, MFOs have full flexibility in shaping their internal structure, typically creating teams responsible for given subject areas — e.g., corporate legal advice, investment advice, succession issues. Due to the size of MFOs, they rarely form formal departmental structures. Banks’ organizational freedom is to a certain extent limited as there are structures that a bank is obliged to establish according to the prudential regulations — e.g., an audit committee and a remuneration committee. In other areas, banks have greater flexibility, usually creating divisions and departments responsible for particular types of banking services (retail, corporate, electronic, and transactional banking) and supporting activities (risk, accounting, IT). By nature, the organizational structure of banks is usually highly developed, and thus more difficult to transform, while MFOs are smaller structures with a greater degree of transparency and flexibility.

3.4. Product dimension

In terms of services offered, the activities of banks and MFOs differ. Banks are the primary provider of services that can be used in serving affluent clients, while MFOs act as agents who draw upon the services offered by banks in creating a comprehensive product plan for a wealthy family, but they can also create their own products, primarily based on consulting activities. Banks can supplement their basic banking services with other services dedicated to affluent clients, which is usually possible thanks to their much greater financial power than in the case of MFOs with much smaller capital bases. At the same time, however, MFOs are able to create a comprehensive product plan based on the offer of many banks, which is a significant competitive advantage.

Table 1 summarizes the analysis.

4. The Market for Multi-Family Offices and Private Banking in Poland

4.1. Data

In order to present the characteristics of the MFO market, a group of seventeen entities was identified that appear to offer the services of a MFO and which also each independently declare that the format of providing their services is family. The data used to present the MFO market in Poland was obtained from the Orbis database provided by Bureau van Dijk (mode including access to all companies), using its tool “Peer analysis” and “Aggregation”. The data includes information on operating income, gross and net financial results, total assets, current liquidity, profit margin, return on capital, and solvency ratio10. These data were supplemented with data obtained directly from the MFOs.

To compare MFOs with credit institutions, data on the banking sector were used as published by the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (2020) and the Bank Guarantee Fund Bank Guarantee Fund (2019).

Given that the latest available data on MFOs in the Orbis database were as of the end of 2018, the banking sector data were also presented as of year-end 2018 to ensure the comparability of the market. As data in the Orbis database are presented in USD, other data were recalculated to USD using the average exchange rate for USD/PLN published by the National Bank of Poland as of 31.12.2018.

4.2. Overview of multi-family offices and private banking in Poland

MFOs in Poland are a niche segment of the financial market. In terms of numbers, there were seventeen entities in Poland whose activities in terms of form, scope of services, and marketing could be considered as MFOs when the research was conducted in May 2020. At the same time, of the 565 commercial and cooperative banks operating in Poland (Polish Financial Supervision Authority, 2020), only ten offered private banking services11 (Korczakowski, 2020). The combined value of Polish banks’ total assets at the end of 2018 was approximately USD 503.70 billion (Polish Financial Supervision Authority, 2020). The total assets of those ten banks offering private banking amounted then to USD 344.85 billion, constituting nearly 70% of the sector — based on the financial statements of the banks at year-end 2018. There are no separate data in regard to the assets of private banking departments in Polish universal banks. At the same time, the value of MFOs assets was only USD 3.13 million (Orbis, 2020). However, it should be noted that family offices do not accept funds from their wealthy clients, they serve only as intermediaries providing services to clients; therefore, clients’ assets cannot be equated with the value of assets of the MFOs. Similar to the private banking segment, data on assets managed by MFOs in Poland are not available. The responses provided by family offices as part of the survey showed that the average value of assets managed for clients ranged from PLN 1-10 million (USD 270,000-2.66 million). The presented data show that the MFO market segment in Poland is small and highly fragmentated compared to banks. While there are more MFOs than banks with private banking departments, the consolidated private banking sector accounts for a greater share of the assets of institutions serving wealthy clients.

On average, MFOs in Poland typically serve from 10-49 clients, but the survey suggests that there could be as many as 1,500 clients of MFOs in Poland. In terms of the number of clients, there are two stand-out MFOs, each of which serve more than 500 clients. At the same time, banks in Poland served approximately 47 million customers (Boczoń, 2019a), but the number of private banking clients is not known. Generally, the group of affluent Poles in 2018 comprised 1.434 million individuals (KPMG, 2019), who were served by various types of institutions: banks including private banking departments, MFOs, and other entities including asset managers. Data confirm that the group of Polish MFOs is strongly differentiated, with two main players in terms of the number of clients12, as mentioned above. Strong contrast is also visible among Polish MFOs in terms of the types of customers that MFOs and banks seek to serve. Within MFOs, the minimum liquid asset threshold for their clients varied from PLN 1,000-100 million (USD 265–26.6 million). Banks were more uniform in terms of the minimum capital requirement to be met in order to become a private banking client. Typically, it was PLN 1 million (USD 260,000) (Juszczyk & Gancewski, 2019).

The difference in the scale of operations is also visible in the number of employees. While at the end of 2018, approximately 50 people worked in Polish MFOs per Orbis (2020), the survey results indicated that on average 22 people worked in a single MFO. The total employment in the nine MFOs that participated in the survey should then be approximately 200 people, while more than 97,000 people worked in the ten universal banks in Poland offering private banking services as of the end of 2018 (Boczoń, 2019b). Once again, there are no data about the number of private banking workers among the total workforce in the banking sector. The survey revealed that MFOs tried to strike a balance between various types of employees, engaging lawyers, business consultants, and investment advisors in similar proportions. The exact profile of private banking employees is not known.

In regard to data comparing the structures of MFOs and banks, the aggregated solvency ratio (the relation of equity to assets) in Polish MFOs at the end of 2018 was 43.88% (Orbis, 2020). At that time, the ratio of equity to assets in banks was approximately 10.77% (Polish Financial Supervision Authority, 2020). Among the banks providing private banking services, that aggregated ratio amounted to 11.4%13. This shows a fundamental difference between MFOs and banks regarding dependence on financing from external sources. It is quite difficult to compare MFOs and banks in terms of their liquidity profile. While MFOs could be described by indicators such as current ratio (current assets/current liabilities) — 2.38 for aggregated MFOs (Orbis, 2020), banks’ liquidity is usually measured by specific regulatory ratios (e.g., LCR, NSFR), which are not comparable to each other.

Although MFOs are much smaller entities than banks, their financial results appear much better. Based on aggregated data for MFOs in Poland, ROE (after tax) at the end of 2018 amounted to approximately 42.80% (Orbis, 2020), while banks at the same time achieved ROE of 8.24% (Bank Guarantee Fund, 2019). It was 8,7% for the ten private banking entities14. The results of these MFOs in Poland were achieved with a relatively high solvency ratio — which ignores the fact that the MFOs’ relatively high ratio results from very thin capitalization. Also, in terms of ROA (after tax), MFOs appear definitely better than banks as a potential investment target. This ratio for aggregated MFOs amounts to 18.78% (Orbis 2020), while for banks it is 0.87% (Bank Guarantee Fund, 2019). Nevertheless, the analysis of profitability suggests that lower relative measures for banks result mainly from their enormous balance sheet size when compared to the MFOs. While profit margin (net income/sales revenue) accounted for 13.14% in MFOs (Orbis, 2020), for banks the ratio amounted to 23%15 (sales revenue calculated as the sum of interest income and fee/charge income).

5. The Competitive Advantages of Multi-Family Offices in Poland – Survey Results

The quantitative analysis was complemented by the survey addressed to representatives of the MFOs in Poland. The survey was conducted between May and September, 2020 by the author by means of direct contact with the representatives of MFOs. Banks did not take part in the survey, justifying their decisions by reference to their specific information policies. Interviews with bank representatives also indicated that banks were not necessarily familiar with the term “family office.”

Ultimately, nine MFOs16 of the seventeen to which a request to complete the questionnaire was sent participated in the survey. It assessed the competitiveness of family offices according to the four analyzed criteria: institutional, financial, operational, and product. In terms of assets, the nine respondents account for about 67% of the Polish family office market.

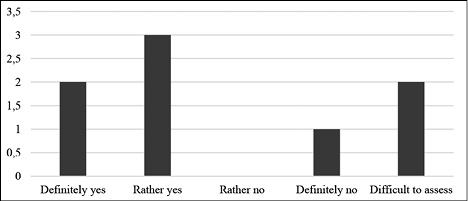

5.1. Assessment of institutional competitive advantages

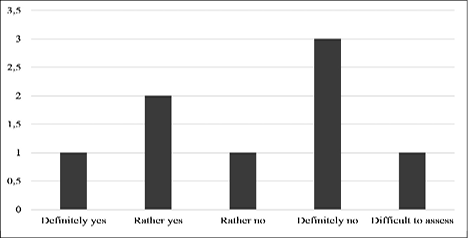

As evidenced in section 3, also in the replies of MFOs it appears that the regulatory environment in which MFOs operate in Poland is much less restrictive than for banks. This, in turn, suggests that these entities have a natural competitive advantage over banks due to this lack of regulatory restrictions and the related costs. Nevertheless, the responses provided by MFOs indicate that they were not convinced of their better position resulting from the regulatory environment compared to banks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Does the regulatory environment in which MFOs operate constitute a competitive advantage in comparison with banks?

Source: research results

The research results presented above may emerge from the general high degree of regulation of the financial market, in the face of which MFOs may still feel overwhelmed by numerous legal complexities. Nevertheless, such results may also indicate a lack of analysis on the part of MFOs as to their place in the Polish legal context relating to the financial market and the resulting benefits.

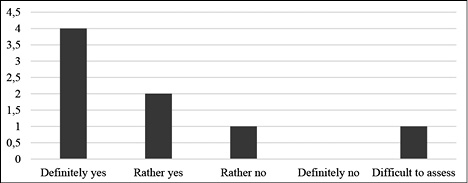

The lack of conviction about the significantly better position of MFOs in terms of the degree of regulation was not duplicated when assessing the supervisory environment in Poland. According to the responses provided by the MFOs, supervision over them is not assessed as too strict. One MFO even admitted that, in its opinion, it does not exist at all in practice (Figure 3). This would indicate that MFOs benefit from a favorable supervisory environment that does not interfere significantly with their activities and allows them to focus on a key area — managing the wealth of their affluent clients. However, the results of the research can also be read as a red flag for the Polish supervisor that it pays too little attention to the activities of MFOs, which means that there is no effective body identifying deficiencies or irregularities in their operation, thus exposing wealthy clients to losses.

Figure 3. How would you assess the supervision of MFOs in Poland?

Source: research results

MFOs, however, were not convinced whether they should be subject to supervision: three entities clearly stated that they should be, while four institutions were of the opposite opinion — i.e., that they should not be supervised — and two MFOs were uncertain on the issue. At the same time, MFOs were inclined to say that the lack of financial supervision over them is a competitive advantage (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Does the status of family offices as companies not covered by the supervision of the Polish Financial Supervision Authority constitute a competitive advantage?

Source: research results

The presented research results suggest that MFOs in Poland are not convinced of their privileged position vis-à-vis banks resulting from a milder regulatory and supervisory environment. On the one hand, this may indicate a passive attitude on the part of MFOs, which are unable to actively identify and use their existing advantages in competition with banks. On the other hand, however, this situation may indicate that, depending on the scale of their operation, some MFOs may feel the burdensome effects of general financial sector regulation in practice, and find them to be so severe that they cannot clearly recognize the offices’ relative position as an advantage. At the same time, the lack of an unequivocal rejection of the proposal for supervision may indicate that MFOs would see such action as a way to increase the credibility of their business, which is crucial in serving wealthy clients.

5.2. Assessment of financial competitive advantages

Comparing the size of MFOs and banks operating in Poland, one could draw the thesis that banks have a natural competitive advantage in terms of financial opportunities, owing to their significant equity and the high volume of assets under management. However, this is not confirmed by the results of the MFO survey in which respondents assessed the position of banks and MFOs in terms of financial strength (evaluated in terms of capital that is available and necessary for entities to effectively provide their services) as basically the same. The former are large entities and have and manage significant capital accounts, while the latter — although much smaller in terms of the value of their own assets — have, however, the financial resources of rich families behind them, which means that in terms of investment opportunities, their strengths may be equal.

Although the financial opportunities of banks and MFOs are assessed similarly, the flexibility of MFOs in terms of pricing is viewed as a clear competitive advantage in the financial area. This enables effective competition with banks that are bound by strictly defined tables of fees and commissions. Although the banks declare on their websites that fees are negotiable, the survey reveals that the degree of meeting client expectations is not as high as in the case of the MFOs. This is the unanimous opinion of the family offices that responded to the survey.

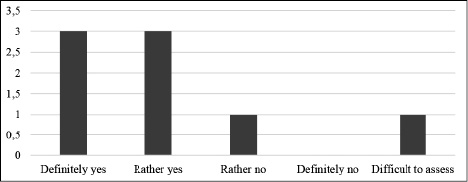

Moreover, in the opinion of a significant proportion of the MFOs, their advantage is not only the flexibility that allows better adjustment of the price of services to the client’s expectations, but also the adopted pricing policy. It was reported that in approximately 56% of MFOs in Poland fees are negotiated individually for activities to be performed on behalf of the client. In addition, it is possible to establish an individual remuneration model. This opinion is shared by five of the nine surveyed MFOs. Only one MFO had the opposite opinion (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Does the pricing policy of family offices constitute a competitive advantage in comparison with banks?

Source: research results

The research results seem to challenge a common myth about the higher costs of serving affluent clients by family offices compared to banks. In the opinion of the MFOs, they are the ones that are able to offer clients a more competitive fee model for their own services, which is always based on fully negotiated remuneration. Moreover, the scale of “negotiability” seems to be significantly higher compared to banks, where advisors can usually only move within designated price brackets. Another issue that speaks in favor of MFOs is the speed of making pricing decisions, resulting from a lean organizational structure, which is another competitive advantage.

5.3. Assessment of organizational competitive advantages

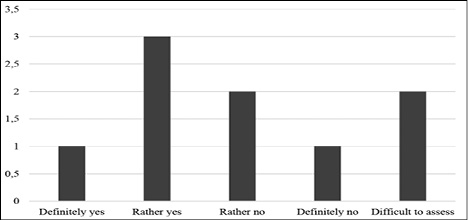

The surveyed MFOs unequivocally stated that they have greater freedom in terms of the internal organization of their activities compared to banks whose structures are extensive and rigid. Most of the surveyed MFOs agreed with the statement that this method of operation allows for greater flexibility in the provision of services to wealthy clients in every respect — i.e., in terms of pricing policy, the scope and format of offered products, the format of service provision, the speed of investment plan execution (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Does the way of organizing family offices’ activities allow for greater flexibility in providing services to wealthy clients?

Source: research results

This assessment indicates another competitive advantage of MFOs in Poland, which is the ability to quickly adapt to the changing environment and clients’ expectations. The existence of this type of competitive advantage was confirmed by the MFOs participating in the survey, which mostly agreed with the statement that the aforementioned way of operating family offices constitutes a competitive advantage in comparison with banks (Figure 7).

The factor contributing to the existence of this kind of advantage may, however, be the regulatory environment underestimated by MFOs in Poland. It should be underscored that MFOs are not subject to the regulatory requirements that require banks to create well-developed departmental structures. Moreover, many procedures in banks are controlled by regulations or supervisory guidelines, which reduce their flexibility due to the necessity to involve many people in the bank in one process — e.g., in the area of sales, analysis, risk. Therefore, the greater flexibility resulting from the way MFOs are organized and operated in Poland is naturally unavailable to banks due to the legal framework in which they must operate.

Figure 7. Does the way of organizing family offices’ activities constitute a competitive advantage?

Source: research results

Source: research results

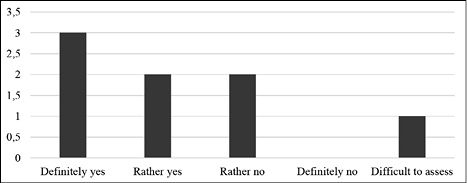

5.4. Assessment of product competitive advantages

The surveyed representatives of MFOs unanimously assessed that they are entities whose schedule of services is much broader than that of banks and much better suited to the needs of wealthy clients. At the same time, however, representatives of MFOs were not so firm in the assessment of whether the product offer constituted a competitive advantage for family offices over banks (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Does the family offices product offer constitute a competitive advantage in comparison with banks?

Source: research results

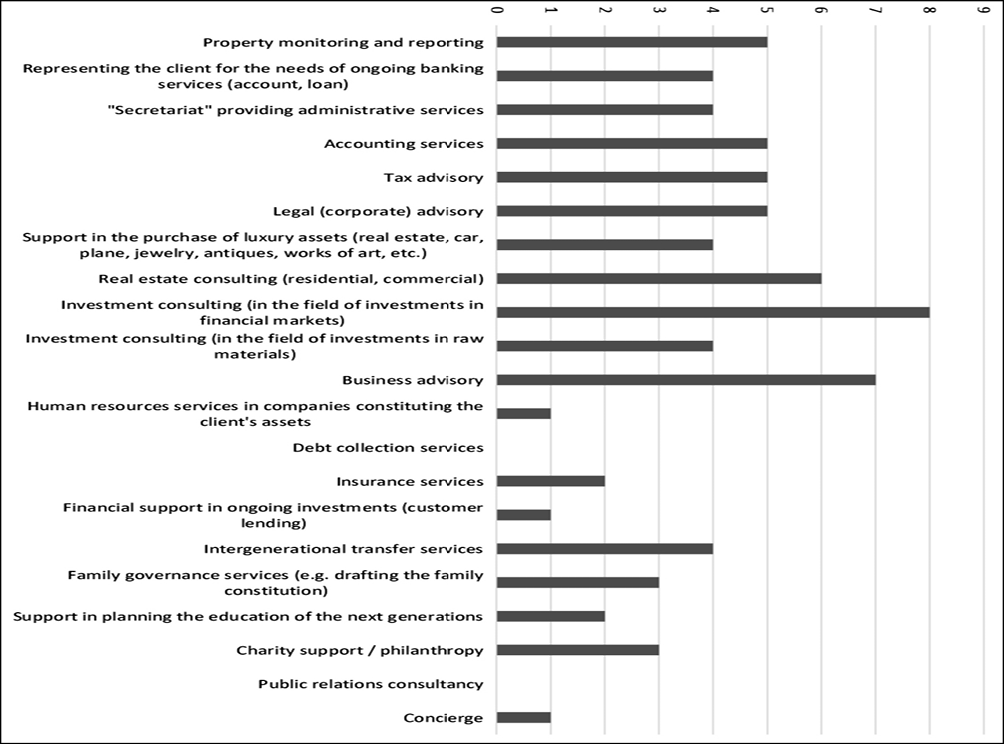

It should be emphasized, however, that although the services offered by MFOs in Poland may better meet the needs of wealthy clients than banks as the entire activity of MFOs focuses on serving exactly this segment of clients, it still differs from international standards in terms of the range of available products and services (Figure 9).

As shown by the results of the survey conducted among representatives of Polish MFOs, not all services that constitute the standard range of family offices services in the most developed markets are available in Poland. Underdeveloped areas are support services such as concierge, services related to planning the education of the youngest family members, and in regard to philanthropic activities. Moreover, although it would seem that the basic service of MFOs should be monitoring and reporting on assets, it is not the dominant type of service for MFOs in Poland. Their primary service is advising on financial market instruments. Polish banks active in the private banking field also suggest that financial investment consulting is the most important part of their activity in serving wealthy clients. The MFOs’ profile also suggests that they are companies primarily with an advisory role in the financial sphere of their wealthy clients’ lives, but that they aspire to evolve toward full-service MFOs by gradually expanding their offer. Nevertheless, although Polish companies specializing in serving wealthy families define themselves as family offices, their current scope of services calls into question whether the accepted definition for this type of entity justifies their use of the label. Here, however, it should be noted that the service of affluent clients in Poland is developing along with the increase in the level of clients’ wealth. Hence, the demand for certain services has so far been low and, therefore, MFOs may not have developed them.

Figure 9. The scope of multi-family office services in Poland

Source: research results

6. Summary and Recommendations

Family offices are a widely used type of institution supporting the wealthiest families in the world. One form of operation is the MFOs serving several rich families simultaneously. Entities of this type are active in Poland and their activities can be viewed as competition to local banks operating in the private banking segment. The aim of the article was to assess whether MFOs offer real competition to private banking in Poland. In this regard a few theoretical and practical implications should be noticed.

It should be emphasized that MFOs, regardless of identified competitive advantages (main being regulatory environment), remain a marginal and fragmentated part of the financial market in Poland — in terms of assets, number of clients, and employees. This undermines the theoretical assumption that descriptively identified competitive advantages, especially legal and regulatory requirements, determine the competitive power of newly establish entities. The key to the success of new types of financial institutions depends on a wide range of factors, among which financial, social and behavioral issues have significant impact.

Moreover, Polish MFOs are strongly differentiated, with some pursuing a model of rapid customer base expansion, which makes them closer to banks in terms of their operating model. The practical implication for MFOs is however – taking into account its marginal role in the financial system – that in the face of their definitely smaller financial power, they might be interesting target of takeovers by banks.

The entities that were included in the group of Polish MFOs due to their form of operation, schedule of services and marketing remain — when compared to family offices elsewhere in the world — still underdeveloped, as evidenced by the comparatively incomplete catalog of services they offer. This situation, however, results from the current phase of Polish economic growth: large family estates have been growing here for about 30 years, which means that only in recent years has there been an increasing demand for services provided by MFOs. The low level of development — compared to the leading family office markets elsewhere — may not be the result of the passivity of Polish MFOs, but rather the level of development of the demographic segment in which they operate. Undoubtedly, however, MFOs will also develop along with the increase in the wealth of Polish society. However, their role in the financial system depends on how effectively they will compete with other financial institutions that are also lively interested in the extending their portfolio of clients by affluent ones (e.g., banks, asset managers, law firms). Identification of competitive advantages vis-à-vis their main competitors in the field of serving wealthy families — i.e., banks — may be an important factor for family offices in the struggle to win the plum job of wealth management for Poland’s most affluent people. From the practical point of view, it seems that the current situation of Polish wealthy clients – the time when as indicated at the beginning of the article in major part of family enterprises generation transfer of wealth is planned to be conducted – might be a good occasion for MFOs to expand, filling this niche market, that is still underdeveloped, also in terms of banks’ offer.

When comparing MFOs and banks serving wealthy clients in Poland, it should be emphasized that they do have many competitive advantages. They benefit from greater flexibility of operation resulting from lower regulatory requirements, greater organizational freedom, and fewer pricing policy constraints. MFOs operating in Poland are definitely more flexible institutions than banks operating in the private banking field. Within the analyzed aspects (institutional, financial, organizational, and product), MFOs generally assessed themselves as entities offering much more competitive services. The research results, however, should be somewhat concerning for MFOs and therefore should be taken by them as an important practical suggestion were to look for and how to utilize the competitive advantages that they have over the banks. Although their strength as reflected in the survey results is undoubtedly flexibility in various fields as Polish MFOs scored better than banks in almost all areas, they remain a niche type of entity on the market. This raises concerns as to whether Polish MFOs are able to effectively use the competitive advantages at their disposal. This is especially important now when MFOs are developing, and they need to win the battle with banks to make wealthy clients aware that there is the opportunity to have a real family office outside of a bank.

It is worth adding here that the scale of their activity is currently too small to constitute a real threat to private banking in Poland. Although, as a rule, MFOs by their very nature are competition for banks serving wealthy clients, due to the low level of development of the field in Poland, they are not currently able to compete with banks in real terms.

Although the research and survey were conducted in relation to the Polish financial system, it seems that the theoretical and practical implications presented above might be useful for MFOs also from other countries. The conclusions might be especially vital for emerging countries with growing number of affluent citizens and their wealth, where the financial system (in terms of institutions and concerning them regulations) is dominated by one type of entities, usually banks.

The research presented in this article has its limitations. Firstly, it should be noted that it constitutes the first attempt to quantify and analyze the functioning of the MFOs in Poland. Their activity has not been scientifically analyzed so far. MFOs are not popular, and the available data are extremely scarce. Narrow scope of available data, short data series (since they are quite young entities on the Polish market), as well as low willingness of MFOs to provide data about financial and operational aspects of its functioning prevented from the more in-depth analysis. Secondly, full assessment of competitive advantages of MFOs versus banks would be more exhaustive, if also banks would take part in the evaluations. This would complement the analysis by the second, opposite point of view.

References

Alińska, A. (2012). Financial safety net as an element of the stability of the banking sector. The Quarterly of the College of Economic and Social Studies and Work, 4, 87–99. https://ssl-kolegia.sgh.waw.pl/pl/KES/czasopisma/kwartalnik/archiwum/Documents/AAlinska8.pdf

Amit, R., Liechtenstein, H., Prats, M. J., Millay, T., & Pendleton, L. P. (2008). Single family offices: private wealth management in the family context. Business, Wharton Global Family Alliance, April

Bank Guarantee Fund (2019). Financial situation in the banking sector as of December 31, 2018. https://www.bfg.pl/wp-content/uploads/informacja-miesieczna-2018.12-www.pdf

Benevides, J., Hamilton, S., Flanagan, J., Mihailidis, M., Fride, B., & Schneeberger, M. (2009). Family office primer: purposeful management of family wealth. Chicago, IL: Family Office Exchange (FOX).

Boczoń, W. (2019a). PRNews.pl report: Number of customers in banks - Q4 2018. https://prnews.pl/raport-prnews-pl-lkieta-klientow-bankach-iv-kw-2018-441787

Boczoń, W. (2019b). PRNews.pl report: Employment in the banking sector – Q4 2018. https://prnews.pl/raport-prnews-pl-zatrudnienie-sektorze-bankowym-iv-kw-2018-441959

Capgemini (2020). World Wealth Report 2020.

Curtis, G. (2001). Establishing a family office: a few basics. American History

Decker-Lange, C., & Lange, K. (2013). Exploring a secretive organization: what can we learn about family offices from the public sphere? Organizational Dynamics, 42(4), 298-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.07.008

Deloitte (2017). Challenges for family businesses. Family constitution and succession plans. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/pl/Documents/firmy-rodzinne/pl_firmy_rodzinne_katowice_20017_KonstytucjaRodzinna.pdf

Deloitte (2019). 2019 family office trends. What’s next for single family offices? https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ch/Documents/privatemarket/deloitte-ch-2019-family-office-trends.pdf

Dromberg, J. (2019). Towards a new generation of venture capital and private equity limited partners: the distinctive rise of Europe’s family offices. June 2018.

Dunn, L. (1980). The family office as a coordinating mechanism within the ruling class. Insurgent Sociologist, 9(2-3), 8-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/089692058000900202

Fernández-Moya, M., & Castro-Balaguer, R. (2011). Looking for the perfect structure: the evolution of family office from a long-term perspective. Universia Business Review, 32, 82-93.

Habbershon, T., Williams, M., & MacMillan, I. (2003). A unified systems perspective of family firm performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 451-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00053-3

Hartley, T. (2015). Family constitutions - what, when and why. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=e5d5c264-e453-4d03-b1a6-b93f958f9f17

Jaffe, D. T., & Lane, S. H. (2004). Sustaining a family dynasty: key issues facing complex multigenerational business- and investment-owning families. Family Business Review, 17(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00006.x

Juszczyk S., & Gancewski, K. (2019). Offer of private banking of key banks in Poland - State and perspectives. Polityki Europejskie, Finanse i Marketing, 21(70), 68-79.

Kammerlander, N., & Schickinger, A. (2019). Family offices - The new private equity firms? In: Financial Yearbook Germany/EU 2020, 118-126.

Korczakowski, D. (2020). List of private banking services as of June 30, 2020. http://privatebanking.xip.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/zest67.pdf

KPMG (2019). Market of luxury goods in Poland. Luxury through the generations. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pl/pdf/2019/12/pl-raport-kpmg-w-polsc-pt-rynek-dobr-luksusowych-w-polsce-2019.pdf

KPMG (2021). Market of luxury goods in Poland. XI Edition. March

Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Technology of Poland (2019). Family foundation. Green book. Warsaw

OECD (2002). The OECD Issues The List of Unco-operative Tax Havens. http://www.oecd.org/ctp/harmful/theoecdissuesthelistofunco-operativetaxhavens.htm

Orbis (2020). Bureau van Dijk. https://orbis.bvdinfo.com/version-2020814/orbis/1/Companies/Search

Polish Financial Supervisory Authority (2019). UKNF announcement on entities offering wealth management services. https://www.knf.gov.pl/knf/pl/komponenty/img/Komunikat_w_sprawie_podmiotow_oferujacych_usługe_zarzadzania_majatkiem_64302.pdf

Polish Financial Supervisory Authority (2020). Monthly data on the banking sector - May 2020. https://www.knf.gov.pl/?articleId=56224&p_id=18

Rivo-López, E., Villanueva-Villar, M., & Vaquero-García, A. (2016). Family office: a new category in family business research? Documento de Trabajo 1/2016 de la Universidad de Vigo. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3306.2003

Rivo-López, E., Villanueva-Villar, M., Vaquero-García, A., & Lago-Peñas, S. (2017). Family offices: what, why and what for. Organizational Dynamics, 46(4), 262-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.03.002

Rivo-López, E., Rodríguez-López, N., & González-Sánchez, B. (2013). The family office in Spain: an exploratory study. Management Research, 11(1), 35-57. https://doi.org/10.1108/1536-541311318062

Russ, A. P. (2018). What is a virtual family office? https://www.forbes.com/sites/russalanprince/2018/11/09/what-is-a-virtual-family-office/#138f558659d2

Ślązak, E. (2018). Private banking. In: Zaleska, M. (ed.). Banking World. Difin.

Tudini, E. (2005). The state of the art of the multi-family office. In: Caselli S., & Gatti S. (eds.). Banking for family business: a new challenge for wealth management (163-190). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27220-8_7

UBS (2020). Global Family Office Report 2020. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealth-management/uhnw/global-family-office/global-family-office-report-2017.html

UBS, & Campden Research (2019). The Global Family Office Report. Available in: https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealth-management/uhnw/global-family-office-report/global-family-office-report-2019.html

Ventrone, D. (2005). Family office: which role in Europe? In: Caselli S., & Gatti S. (eds.). Banking for family business: a new challenge for wealth management (137-162). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27220-8_6

Warwick-Ching, L. (2017). Family offices: a history of stewardship. https://www.ft.com/content/403a2cb4-a9cb-11e7-ab66-21cc87a2edde (accessed 11.12.2021).

1 This includes only those entities whose main area of activity is the provision of family office services (to a full or limited extent) to wealthy families. Thus, it does not include, for example, large consulting companies which, in addition to advisory services, also provide family office services (e.g., KPMG Polska) or law firms that provide legal advisory services for wealthy clients, which are one of the functions of family offices.

2 As a supplement to this information, expanding the segment to include consulting companies providing services called “family office” and law firms specializing in services for affluent clients, both of which were included in the rankings of family office services in Poland, the number of family offices is twenty-eight as of 2020. There is also one company (not included in the quoted numbers) which, although it published information about its family office offer on its website, when contacted, stated it did not provide such service. In addition, there is another company that claims to provide family office services but has been recognized by the Polish supervisory authority as performing banking activities without the appropriate permit. Consequently, a suit was initiated in the prosecutor’s office against that entity.

3 In the opinion of some representatives of family offices, they do not compete with banks because they are entities with a different activity profile. As a consequence, banks are seen as partners of family offices with which they cooperate to provide comprehensive services to wealthy families — banking services being one of the areas in which family offices are supported by banks. While it can be agreed that this is how the division of tasks between entities in this market segment may appear, an analysis of the respective services offered by banks (i.e., private banking) and by family offices suggests that both are trying to entice their clients with a similar range of services. Both groups of entities operating on the Polish market use the phrase “family office” as a category of service they offer. For this reason, it was decided to analyze banks and MFOs as competitors. It should be noted, however, that family offices are naturally forced to cooperate with banks because, as unlicensed entities in Poland, they cannot accept funds from clients and put them at risk.

4 In this article, the terms bank and credit institution are considered interchangeable.

5 Banks refused to take part in the survey, explaining that such a decision results from their “sponsorship policy” or information policy. The reluctance to participate in the survey may also result from the lack of knowledge of the concept of “family office” — a likely conclusion drawn after interviews with bank representatives.

6 Some proposals of definitions might be found in the articles following authors: Amit et al. (2008); Benevides et al. (2009); Dromberg (2019); Fernández-Moya & Castro-Balaguer (2011); Jaffe & Lane (2004); Rivo-López et al. (2013, 2016, 2017); UBS & Campden Research (2019); Welsch et al. (2013); Yadav (2012).

7 However, this limit applies only to the US market. Research carried out in the first decade of the 21st century has shown that European family offices are characterized by a much lower threshold of liquid assets necessary to gain access to these services. Moreover, the research suggests that the American culture of capitalism, in which the economic calculation is much more important than building long-term relationships with clients, promotes multi-family offices. At the same time in Europe, single-family offices operating in accordance with the principles of relational finance were more popular (Tudini, 2005, pp. 170, 175-176), although, paradoxically, single-family offices should be structures for which the minimum size of assets should be higher due to higher absolute operating costs that cannot be shared among other families.

8 Private banking in Poland is provided within the structure of universal banks; therefore, the features of MFOs are compared against the features of universal banks. As private banking is one service that banks provide, this activity must comply with all requirements applicable to universal banks.

9 From a subjective point of view, the activities of MFOs are not regulated in Poland. From the operational point of view, MFOs conduct activities similar to those of a brokerage house or investment firm. If they obtain appropriate licenses, then they are subject to supervision. However, MFOs operating in Poland generally do not have such licenses, which leads to the situation in which they conduct regulated activities but without a permit, as noted by the Polish supervisor (Polish Financial Supervision Authority, 2019).

10 Data available upon request to the author.

11 The group comprised: PKO BP SA, Getin Noble Bank SA, BNP Paribas Bank Polska SA, Bank Handlowy w Warszawie SA, ING Bank Śląski SA, Pekao SA, Bank Millenium SA, Santander Bank Polska SA, Alior Bank SA, and mBank SA.

12 This makes them even more like banks, which are also focused on expanding their customer base. This contrasts with the typical MFO, which serves just a few families, keeping the group of clients not so numerous in order to maintain the selective and elite character of services. Such a conclusion proves the legitimacy of this study.

13 Own calculations based on banks’ financial statements.

14 Ibidem.

15 Ibidem.

16 One family office abstained from providing response to some questions. Therefore, Figures 2, 5-8 show results for eight MFOs.