European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 80-99

The Role of Family Management and Management Control Systems

in Promoting Technological Innovation in Family SMEs

Feranita Feranitaa*, Daniel Ruiz-Palomob, Julio Diéguez-Sotob

a Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia

b University of Malaga, Málaga, Spain

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10, O32

KEYWORDS

Family firm, SME, Family management, Management control systems, Technological innovation

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10, O32

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, PYME, Gestión familiar, Sistemas de control de gestión, Innovación tecnológica

Abstract This paper seeks to resolve the controversy regarding the relationship between family management and technological innovation outcomes. In contrast to prior studies, we focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and go beyond the traditional input-output statistical analysis, by introducing the mediating effect of the use of management control systems (MCS). We also further examine heterogeneity among family SMEs, studying whether a greater family management influences, directly or indirectly, on technological innovation outcomes. Our results from a data consists of 199 Spanish family-owned small and medium enterprises (FSMEs) were not able to indicate a significant direct influence of the level of family management on technological innovation outcome but supported the notion that the utilization of MCS mediated the above relationship.

El papel de la dirección familiar y los sistemas de control de la gestión en el fomento de la innovación tecnológica en las PYMES familiares

Resumen Este trabajo participa en el debate académico sobre la relación entre la gestión familiar y los resultados de innovación tecnológica. A diferencia de estudios anteriores, nos centramos en pequeñas y medianas empresas (PYMES) y vamos más allá del tradicional análisis estadístico input-output, introduciendo el efecto mediador del uso de los sistemas de control de gestión (SCG). También examinamos la heterogeneidad entre las PYMES familiares, estudiando si una mayor gestión familiar influye, directa o indirectamente, en la innovación tecnológica. Nuestros resultados, obtenidos a partir de una muestra de 199 PYMES familiares, no pudieron confirmar una influencia directa significativa del nivel de gestión familiar sobre los resultados de innovación tecnológica, pero confirmaron que la utilización de los SCG media en la relación mencionada.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10901

Copyright 2021: Feranita Feranita, Daniel Ruiz-Palomo, Julio Diéguez-Soto

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: feranita@taylors.edu.my

1. Introduction

Technological innovation is frequently described as the collection of activities utilised by firms to compete outstandingly in both domestic and international markets, through which a business conceives, designs, produces, and introduces a new product, service, process or technique (Coccia, 2017; Ireland et al., 2001; Teece 2001; Teece, 1996; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 1999). Research has shown that firms that innovate continuously while being risk-taking, anticipate demand, and position new products/services, may result in stronger performance than those who do not (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). While innovation has shown to be beneficial to firm performance, innovation requires continuous input of resources and risk-taking attitude. In accordance with prior research, this study defines technological innovation by considering both product and process innovation (Freeman, 1976).

The significance of SMEs can be seen through their contribution to the economy worldwide, and majority of them are family owned and managed (Anderson & Reeb, 2003). The importance of researching on family small and medium enterprises’ (FSMEs) innovation ability despite being risk-adverse and unwilling to invest in innovation inputs due to unique family management characteristics can be seen through the increase in research interest in the last decade (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; De Massis et al., 2013; Duran et al., 2016; Sciascia et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the incongruence findings have led to the “paradox of FSME innovation”, calling for more research on how FSME heterogeneity will lead to different innovation outcomes (Calabrò et al., 2019; De Massis et al., 2013; Diéguez-Soto et al., 2016; Duran et al., 2016; Matzler et al., 2015).

In their recent study, Diéguez-Soto and Martínez-Romero (2019) suggest a negative influence of family management on product innovation in a private firm context. However, we still know less about how the level of family management could affect technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs, thus giving us the opportunity of analysing this relationship. Further examining the incongruence and contradictory findings in the existing literature, family management, the same factor that impedes innovation and at the same time enables innovation in family firms, might have been identified as a friend but also as an enemy (Duran et al., 2016; Matzler et al., 2015). Researchers have also called for further investigation on the impact of family SME heterogeneity on innovation output (Filser et al., 2018; Werner et al., 2018).

Furthermore, management control systems (MCS) serve as an important management function within an organization that translate goals, intent, and vision (i.e. strategy) into executable actions. MCS do so both in terms of financial and non-financial variables, thus also incorporating elements from the operational, strategic, and human resource domains. Simons (1995) defines MCS as “the formal, information-based routines and procedures managers use to maintain or alter patterns in organizational activities”. Over the last two decades, the definition of MCS has evolved to include a broad scope of systems, while continuing to provide information for decision making and strategy implementation (Chenhall, 2003; Chenhall et al., 2011; Malmi & Brown, 2008; Simons, 1995, 2005). Specifically, existing research on innovation has highlighted the role of interactive MCS (Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Bisbe & Malagueño, 2009; Davila, 2000; Henri 2006; Lopez-Valeiras, Gonzalez-Sanchez, & Gomez-Conde, 2016), as MCS contribute positively to firm innovative behaviour (Simons, 1995, 2005).

While the application of MCS is expected to improve technological innovation (Chenhall et al,, 2011), the level of family management is also likely to affect how MCS is carried out within a FSME (Helsen et al., 2017; 2017; Tapis et al., 2017). Yet, to date, little research has been done on the implication of the level of family management on the use of MCS in relation to technological innovation. The unique FSME traits, along with socio-emotional wealth (SEW) and family centred non-economic (FCNE) goals, are known to affect how a family firm is being managed, whether professionally or informally (Berrone et al., 2012; Chrisman et al., 2012). Therefore, the level of family management may affect the extend of MCS being utilized for strategic decision-making, where families struggle between ensuring decisions are in line with the culture and value of family firms versus being strategic and professional (Flamholtz, 1983). Nevertheless, family management, through the use of MCS, may encourage a regular reflexive monitoring of rules and patterns (Verhees et al., 2010) and generate debate and free flow of information, which may question the status quo and promote technological innovation (Ylinen & Gullkvist, 2014). Bearing in mind the previous considerations, our research also investigates the mediating role of the use of MCS in the relationship between the level of family management and the achievement of technological innovation outcomes.

Thus, this paper seeks to further examine heterogeneity in FSMEs, specifically, analysing how differences in governance from the family’s involvement in management would lead to different varieties of technological innovation outcomes. In this way, we respond specifically to the call on further examine technological innovation in family business while considering their heterogeneity in regard to the level of family management. We draw from the resource-based view (RBV) (Barney, 1991) and SEW (Gómez-Mejia et al., 2011) perspective and use a database built from a survey sampled on 199 Spanish FSMEs to address our research questions. In particular, we focus on family-owned SMEs, as they often have restricted availability of knowledge, expertise and views (Colombo et al., 2014), their innovation outcomes require a deeper analysis (Sciascia et al., 2015), and they are vital for worldwide economies (Memili et al., 2015). Spain is an excellent context to study SMEs as they represent 99.8% of the firms (Gobierno de España, 2018).

This paper has several theoretical contributions. Firstly, our study contributes to the current debate on heterogeneity in family firms (Calabrò et al., 2019; 2019; Chua et al., 2012; Filse et al., 2018), where we analyse whether technological innovation outcomes are dependent on the degree of family management. Secondly, researchers have recently analysed the heterogeneous precedents and the consequences of the use of MCS in the particular field of family business (Helsen et al., 2017; Hiebl et al., 2015; Oro & Lavarda, 2019). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address, with empirical data, the combination of family management and technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs as antecedent and effect of the utilization of MCS, respectively. Thus, this study goes beyond the input–output conceptual framework (De Massis et al., 2013), providing more evidence on how to improve family firms’ ability to obtain technological innovation outcomes. Specifically, we emphasize the mediating role of using MCS as a key dimension in the relationship between the level of family management and technological innovation outcomes. Hence, this study shows that the impact of the level of family management on technological innovation outcomes depends on the adoption of MCS. Our findings indicate that the degree of family management has an indirect effect on obtaining technological innovation outcomes through the utilization of MCS. Lastly, we draw on RBV and SEW perspectives to justify the hypotheses and explain our findings, somewhat unusual in existing literature on both MCS and innovation topics in family business field (Duran et al., 2016; Helsen et al., 2017), adding new arguments to the current academic debate on FSME heterogeneity and innovativeness.

This paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we review literature and build the theoretical justification of each of the hypotheses in the theoretical background section. Secondly, we outline the research methodology used to answer our research question and test the hypotheses. Thirdly, we test our hypotheses with empirical data and present the statistical findings in the results section. Finally, we discuss our findings and propose future research in the discussion and conclusions section.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Proposed

Family management is found to play a unique role in innovation decisions, which in turn influences technological innovativeness in FSMEs with concentrated ownership (Brinkerink & Bammens, 2018; Classen et al., 2014). On one hand, there is a negative relationship between family management and spending on achieving innovation in FSMEs (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Sciascia et al., 2015). This is largely related to family members being risk adverse in view of limited resources and SEW at stake. On the other hand, FSMEs are found to be able to innovate despite investing less in innovation activities (Classen et al., 2014). Such puzzle leads us to investigate further into the relationship between family management and technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs, looking into the mediating role of MCS and further examine FSME heterogeneity.

Previous literature has agreed that formal controls as part of MCS increase the capacity of a firm to obtain benefits from innovation (Bedford, 2015; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Jørgensen & Messner, 2009; van der Meer-Kooistra & Scapens, 2015). Specifically, a number of studies have found that formal MCS may stimulate and implement creative ideas, which, in turn, lead to greater innovation (Simons, 1990, 1991, 1995). According to Simons, formal MCS increase innovation capability when the use of MCS includes interactive control systems. Thus, formal MCS can be used to expand opportunity seeking and learning throughout the organization, focusing attention and forcing dialogues throughout the organization by reflecting signals sent by top managers (Simons, 1995). Formal MCS can encourage the implementation of new ideas and initiatives (Henri, 2006). Aiken and Hage (1971) claim that there exists a positive relationship between internal communication and innovativeness, with the internal communication facilitating the flow of information and the sharing of ideas necessary to promulgate innovation. Top managers often use internal communication to send messages to the employees on handling strategic risks, put pressure on operating managers, enhance information gathering, incentivize face-to-face dialogues and debates, providing inputs to innovation, and fostering the development of innovation initiatives throughout the organization. Based on the former arguments, some authors have shown that the use of interactive control systems increases innovation in low innovating firms (Bisbe & Otley, 2004). Managerial practices involving the improvement on the use or exchange of information within the organization are able to change the inertia linked to production processes and lead to new process innovation (Hervas-Oliver & Sempere-Ripoll, 2015).

Given that the use of specific MCS encourages a regular thoughtful monitoring of rules and patterns (Verhees et al., 2010) and implies debates and a free flow of information, it may also question the current status quo and promote technological innovation (Ylinen & Gullkvist, 2014). Furthermore, besides the factors originating from the family itself, acquisition of information in family firms, both in terms of the range of information and the speed of obtaining information, is found to be positively related to innovation outcomes in family firms (Craig & Moores, 2006).

2.1. Family management and technological innovation in FSMEs

Schumpeter (1934) argue that the economic development of manufacturing industry is driven by innovation through a dynamic process in which new technologies replace the old, a process he labelled “creative destruction” (Oslo Manual, 2005; Schumpeter, 1976). Research has shown that technologically innovative firms may outperform their non-innovative competitors (Gersick et al., 1997). Technological innovation outcomes involve introduction of new products, services, or techniques (Freeman, 1976), where they are relevant not only at the firm-level but for the entire economy as they create economic value and growth (Amit & Zott, 2001), as well as superior performance (Lee et al., 2000).

A FSME itself is a different organization type with its various distinct characteristics and governance structure. Filser et al. (2018) have explored how the different functionalities of FSMEs lead to different decisions in terms of innovation process within FSMEs. In general, the innovativeness of a FSME is considered to be influenced by family management, comprising the degree of family involvement, the degree of family control, the risk appetite of the family, the willingness of the family to innovate, and the capability of the family to innovate (De Massis et al., 2013). Hence, the vast prior literature supports the notion that family management affects the rate of technological innovation in FSME (De Massis et al., 2013, 2014; Filser et al., 2018). However, existing literature presents conflicting results with regards to the behaviour of family firms in relation to technological innovation (Kraiczy et al., 2014; Llach & Nordqvist, 2010) and particular findings regarding the impact of family management on technological innovation outcomes still appear to be mixed in public firms (Block et al., 2013; Matzler et al., 2015). Recently, some authors have developed a more fine-grained understanding of the relation between family management and product innovation outcomes in the context of private firms (Diéguez-Soto & Martínez-Romero, 2019).

However, as far as our knowledge is concerned, the study of the relationship between the level of family management, specifically examining further into family firm heterogeneity, and technological innovation outcomes in the context of SMEs is still at its infancy (Filser et al., 2018). Despite the fact that technological innovation is just as essential as it is complicated to accomplish (De Massis et al, 2013) and the importance of this type of companies in any economy worldwide (Memili et al., 2015).

In the family business sphere, due to the interactions between family unit, business entity, and individual family members, unique systemic conditions are originated, producing a large number of unique resources and capabilities (Chua et al., 1999; Zahra et al., 2004). As FSMEs own human, social, physical, or financial capitals that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN), they have the potential to generate sustainable competitive advantages (Barney, 1991). Considering how family management affects the deployment of resources (Sirmon & Hitt 2003), the particular involvement of family members who manage the firm may exert a complex influence on technological innovation. This may enhance our comprehension of how the conformation of the top management team impacts on the process of generating technological innovation (Ridge et al., 2017).

Following this vein, studies based on RBV (Barney, 1991) suggest that family firms possess distinctive capabilities and resources (e.g., social capital configurations) that contribute to their innovation success (Classen et al., 2014; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Some researchers argue that family firms are more innovative because they possess unique characteristics of their human, social, and marketing capital (Llach & Nordqvist, 2010), and because of their more flexible structure and decision-making process (Craig & Dibrell, 2006). Furthermore, family firms are further said to be able to adopt and implement decisions quickly and with more stamina (König et al., 2013). Especially in the case of FSME, the unification of ownership and management allows the family to have a large degree of control on the utilization of resources in various aspects (Brinkerink & Bammens, 2018; Memili et al., 2015).

In addition, companies with a higher level of family management are under less pressure to obtain high short-term profits and have a greater long-term vision than other types of companies, which in turn, can promote entrepreneurial strategies and innovativeness (Casillas & Moreno, 2010). Family-managed firms tend to establish close ties with selected stakeholder groups, characterized by enduring commitment and trust, which can further stimulate product and process innovation through the exchange of new ideas (Classen et al., 2014; Sciascia et al., 2012). Therefore, the former arguments suggest that a larger degree of family management promotes unique resources and capabilities that increase family firm’s ability to obtain technological innovation outcomes.

Yet, according to behavioral theory, family managers make decisions based more on protecting SEW (but with uncertain economic profit) than on increasing economic benefits (but a subsequent decrease of SEW), being the loss of SEW the main driver of the strategic behavior of family firms (Berrone et al., 2010; Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). In some circumstances, family managers might not take into account economic rationality nor profitability in their decisions (Casillas et al., 2010; Chrisman et al., 2012) since such family-focused decisions are not aligned to the company mission and strategic plan. Also, decisions that are profit driven and economically rational may need significant investments and/or redesigning the culture, processes, and organizational structures (Zahra, 2005). The motivation behind such behavior is due to the fact that protecting family welfare then assures the longevity and control of the firm (Brinkerink & Bammens, 2018; Chen & Hsu, 2009), as existing research has shown how family managers can exert a conservative and risk aversion behavior (Chrisman et al., 2012; Donckels & Frolich, 1991). As technological innovation implies risk, strong commitment of resources, difficulty to predict results, need for external financing, and appropriate skilled human resources (Chrisman et al., 2014), FSMEs may be less willing to take the risk to innovate.

Consequently, the greater ability that family managers are believed to have in combination with family firms’ unwillingness to innovate may have contrary effects on technological innovation outcomes and might explain the different findings and arguments in the existing research with respect to the effect of family management on technological innovation. The greater ability possessed by family managers stems from greater resources derived from family firm unique characteristics, such as social capital and governance structure (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Yet the tendency to protect SEW may hinder family managers from utilizing these resources to innovate. Seeing that net effect of family management on technological innovation in FSMEs is ambiguous, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: The level of family management positively affects technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs

H1b: The level of family management negatively affects technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs

2.2 The mediating role of MCS between the level of family management and technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs

Typically, MCS are considered as a set of tools used by organizations to ensure the effective use of resources to achieve desired employee behaviour, and the implementation of strategic organizational goals (Chenhall, 2003). As the topic evolved over the last decades, research branched out into several different approaches towards the use of MCS: financial information-based control, formal/informal control, result control, and behavioural control. Simons (1995) broadened management control to incorporate competing goals other than financial performance such as innovation, and the need to balance both positive and negative forces to steer the organization while simultaneously allowing for learning and renewal. Based on informational aspects, Simons (1995) defines MCS as “the formal, information-based routines and procedures managers use to maintain or alter patterns in organizational activities”.

The systems utilized for management control often include external information, non-financial information, predictive information, and both informal personal and social controls (Chenhall, 2003; Ittner & Larcker, 2001). Although some firms choose to use formal practices, rules, procedures and standards, other businesses rely more on subjective judgment (Speklé, 2001). In modern times, companies face competing business demands in an uncertain and dynamic environment. “Increasing competition, rapidly changing products and markets, new organizational forms, and the importance of knowledge as a competitive asset have created a new emphasis that is reflected in such phrases as market-driven strategy, customization, continuous improvement, meeting customer needs, and empowerment” (Simons, 1995).

The existing literature has investigated some determinants of MCS usage in family business, such as generational stage (Michiels et al., 2013), professionalization and succession within family management (Giovannoni et al., 2011), firm size (Speckbacher & Wentges, 2012), family value (Oro & Lavarda, 2019), emotional attachment (Tapis et al., 2017), and life cycle stages (Moores & Mula, 2000). Other studies have also suggested that MCS are used to a lesser extent by family firms (Craig & Dibrell, 2006; Songini & Gnan, 2015; Speckbacher & Wentges, 2012). However, there is an obvious need for MCS in FSMEs, due to the fact that family members are often involved in various overlapping roles, such as owners, managers, directors, and other key decision-making positions (Barbera & Moores, 2013; Werner et al., 2018). In such case, the use of MCS may decrease altruism, and thus promote efficient collaborations and information exchange (Kim & Gao, 2010).

Prior studies have recognized that the degree of family management may affect how and to what extent family businesses consider the gains and losses of SEW as their main frame of reference in their decision-making, which will ultimately determine the results of technological innovation (Berrone et al., 2012). Subsequently, family management may also affect the use of MCS. For example, family management may lead to utilising management control to transmit and consolidate the intended culture and values of a FSME throughout the organization strategically by means of its centralized decision-making (Flamholtz, 1983). Also, a higher family management may prompt the implementation and use of MCS as they influence how family firm culture is shaped through time (Herath et al., 2006). Likewise, as the level of family management increases, there will be a higher emphasis on long-term orientation or non-economic goals, which may in turn also augment the use of MCS (Senftlechner et al., 2015). For instance, family managers with long-term perspectives may instruct and monitor their staffs on improving the development of family SEW, particularly with regards to MCS implementation, because they inherently preserve the codes, norms, and values of the FSMEs (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011)

On the other hand, family management, the factor that was found to be both enabling and impeding innovation in family firms can also reduce a FSME’s willingness to utilise MCS. For example, FSMEs, due to their size where they rely more on mutual trust and clan control, may be less inclined to adopt and implement professionalization (Dekker et al., 2013; Posch & Speckbacher, 2012). Moreover, family members managing FSMEs may also be limited in terms of knowledge and training to implement MCS (Rausch, 2011). Existing research has also shown that greater level of family influence leads to higher level of family control and lower degree of formalization, thus lowering the utilization of MCS (Hiebl et al., 2015). Another unique trait of family business, altruism, also attribute to a difference governance structure and hiring system within a FSME, therefore may lead to lower usage of MCS (Davis et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, the availability of internal references, such as financial resources availability, existing knowledge availability, cost structure, or profitability, provides crucial information enabling family managers to make decisions. We expect that the consistent use of MCS would act as an internal reference on a FSME’s context, as such aiding the owning family in their decision-making by providing a broad range of rationales. When managers possess sufficient and appropriate information, they will be more likely to generate and apply creative ideas and initiatives (Henri, 2006; Simons, 1995), as well as alter the rigidity involved in production processes (Hervas-Oliver & Sempere-Ripoll, 2015), thus increase the chance of obtaining technological innovation outcomes. Therefore, taking into account the above arguments, we may conclude that the proper use of some specific MCS can have a positive impact on technological innovation in FSME. MCS therefore act as a mediating catalyst of the effect of the level of family management on technological innovation outcomes, where it stimulates the best and unique features of FSMEs.

If the level of family management is related to the use of MCS and the use of MCS is related to technological innovation outcomes, then the degree of family management can be expected to have implications for technological innovation outcomes through the induced increase in the use of MCS. Hence, an indirect effect of the level of family management acting through the use of MCS on technological innovation outcomes may be proposed. There should be a relationship between the level of family management and firm technological innovation outcomes, which may be explained in part by an indirect effect whereby family management impacts on the utilization of MCS and in turn influences the probability of technological innovation outcomes. This can be formally expressed as:

H2: The use of MCS mediates the relationship between the level of family management and technological innovation outcomes in FSMEs.

3. Methodology

3.1 Sample and Data

This study is based on data sampled on Spanish FSMEs by means of a survey sent to 199 managers of FSMEs in Spain, following the European Commission (2003) recommendation on defining a SME. The sample selection process was designed to characterize the structure of the country, following the stratified sampling principles in finite population. The population of sample firms was segmented by industry and size. The size of each stratum of the sample was determined proportionally to that of the population, according to the Spanish Statistical Institute database (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). We replaced firms that chose not to participate in the project or did not complete surveys with similar (randomly selected) firms in the same industry and geographical area. Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample.

Table 1. Distribution of the sample

|

Size (employees) |

Generation |

Gender of CEO |

CEO familiar |

Total |

|||||||

|

Industry |

Micro |

Small |

Medium |

1st. |

2nd. |

3rd. + |

Woman |

Man |

Yes |

No |

Sample |

|

Manufacturing |

27 |

34 |

13 |

19 |

43 |

12 |

14 |

60 |

66 |

8 |

74 |

|

Construction |

22 |

14 |

3 |

16 |

19 |

4 |

2 |

37 |

38 |

1 |

39 |

|

Trade |

21 |

15 |

6 |

10 |

27 |

5 |

6 |

36 |

39 |

3 |

42 |

|

Services |

18 |

15 |

11 |

22 |

21 |

1 |

8 |

36 |

37 |

7 |

44 |

|

Total sample |

88 |

78 |

33 |

67 |

110 |

22 |

30 |

169 |

180 |

19 |

199 |

We collected information through phone interviews with each of the firm managers of the sample FSMEs between September to November 2017, using a questionnaire addressed particularly to firms’ managers. FSME managers are found to be the most important decision makers (Van Gils, 2005), and managerial perceptions exert a significant degree of influence towards the firm’s strategic behaviour (O’Regan & Sims, 2008).

Furthermore, we analysed the representativeness of the sample through its power analysis, by using G*Power software. We estimated a priori sample size of 109 survey respondents with the following specifications: Family is F-test family, statistical test is linear multiple regressions (fixed-model, R2 deviation from 0), and the type of power analysis is a priori (computing required sample size given α = 0.05, po-

wer = 0.80, and effect size = 0.15 with 8 predictors). Then, since we collected 199 questionnaires, we estimated post-hoc achieved power of 0.998 (given α=0.01, sample size of 199, and determining the effect size from predictor correlations as f2 = 0.2386).

3.2 Variables

3.2.1 Dependent variable - Technological innovation

Existing research and the process-based conceptualization of technological innovation have identified two types of innovation: product innovation and process innovation (Damanpour, 1991). In this sense, we consider technological innovation as a second order construct that aggregates two first order composites: product innovation and process innovation (Aljanabi, 2017). Both of them are measured through 5-points Likert scale with three indicators.

3.2.2 Independent variable - Family management

We consider a family firm as an organization with particularistic vision and goals for the business, a vision that is developed by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families, with the goal to sustain across generations of the family or families (Chua et al., 1999). As proposed by Chrisman et al. (2010), the indicators for family vision and goals would be family ownership and involvement in the management, as these allow the family to influence firm decisions in achieving intended goals. Therefore, we adopt the proposition that has been widely accepted by existing research, which is to use family ownership and family involvement in the management to identify a firm as a family-managed firm. Our definition of family-managed firm is restrictive in comparison to others in the literature. Particularly, we use a dummy variable that takes values 0 and 1, to differentiate family firms from non-family firms in the selection of the sample. Then, for all those firms that are family owned, we measure family involvement in the management through a 5-point Likert scale. Respondents were asked if family members occupy the majority of managing positions (Kotlar et al., 2013). With the owning family retaining proprietorship and being involved in the top management, this translates the family’s vision and goals in the family firm. Previous studies in this field have used the same measurement to capture the perspective of family-managed firms (Diéguez-Soto et al., 2016).

3.2.3 Mediating variable - Management control systems

Although the concept of MCS is an emerging issue, and its definitions, dimensions, functions and scope have yet to be established academically (Berry et al., 2009; Chenhall, 2003; Hared et al., 2013). Nevertheless, heterogeneous formal MCS are likely to be applied mostly in complex firms (Otley, 1999). Thus, it was required for the purposes of this study to limit a restricted number of very specific control mechanisms that are especially suitable for our research goals. Existing research has shown how specific control mechanisms at different levels in organizations foster innovation (Bedford, 2015; Bisbe & Malagueño, 2012; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Davila, 2000; Lopez-Valeiras et. al., 2016; Mackey & Deng, 2016).

With the top managers strongly involved in decision-making in relation to technological innovation, diagnostic control systems aid management level to clearly define and precisely specify goals based on the desired outcomes (Bedford, 2015). Though diagnostic control systems provide the goals to be achieved, it does not provide the defined steps to achieve the goals. Therefore, the use of interactive networks lay out the procedures for all levels in the organization to follow in pursuit of the goals defined to top level management (Simons, 2005). The use of interactive control systems provides information for management level to make decision, as well as facilitates the flow of information for members of the organization at all levels to implement effectively and efficiently (Bisbe & Malagueño, 2012; Bisbe & Otley, 2004; Davila, 2000; Lopez-Valeiras et. al., 2016; Mackey & Deng, 2016).

In measuring MCS, specifically, we focus on the degree of implementation of the following aspects: a) Integrative systems, such as ERP, CRM or SCM; b) Managerial accounting; c) Budgeting control; d) Financial statements analysis; e) Strategical planning control; f) Internal auditing; and g) Quality control. To measure these questions, we created a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates that the firm did not use the corresponding MCS system at all and 5 indicates that it was strongly implemented in the firm.

3.2.4 Control variables

We utilized a set of six control variables in our analysis to exclude alternative explanations for the phenomenon under study. In order to control its effects, we first control the importance of continuous training of family managers with a 5-point Likert scale, where respondents were asked to answer the following question: “There is a permanent and continuous training of family managers”. Secondly, the degree of technological innovation inputs was controlled by a composite of two measures about the evolution in the last two years of R&D expenditures in product development (rad1) or process enhancement (rad2). Thirdly, we controlled for leverage, by using a debt to total assets ratio. Fourthly, we controlled for family firm age to address the possible potential for higher innovation orientation in younger organizations (Uhlaner et al., 2012). Fifthly, we controlled for firm size (Scheppers et al., 2014), measured as the average number of employees in 2015. Finally, industry effects were measured using four-digit NACE codes (Nomenclature générale des Activités économiques dans les Communautés Européennes - NACE).

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations of indicators, while Table 3 summarizes the definition of variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations of measures

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ipd1 |

3.21 |

1.12 |

1 |

5 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

2 |

ipd2 |

3.39 |

1.15 |

1 |

5 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

3 |

ipd3 |

3.18 |

1.00 |

1 |

5 |

0.44 |

0.53 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

4 |

ipc1 |

3.13 |

1.06 |

1 |

5 |

0.36 |

0.42 |

0.31 |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

5 |

ipc2 |

3.18 |

1.22 |

1 |

5 |

0.45 |

0.56 |

0.42 |

0.65 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||||

|

6 |

ipc3 |

2.95 |

1.00 |

1 |

5 |

0.33 |

0.46 |

0.59 |

0.58 |

0.65 |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||||

|

7 |

mcs1 |

3.09 |

1.33 |

1 |

5 |

0.12 |

0.20 |

0.09 |

0.19 |

0.26 |

0.19 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||

|

8 |

mcs2 |

3.50 |

1.21 |

1 |

5 |

0.17 |

0.15 |

0.09 |

0.17 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.44 |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||

|

9 |

mcs3 |

3.63 |

1.23 |

1 |

5 |

0.15 |

0.26 |

0.22 |

0.24 |

0.36 |

0.28 |

0.36 |

0.57 |

1.00 |

||||||||||||

|

10 |

mcs4 |

3.73 |

1.17 |

1 |

5 |

0.19 |

0.27 |

0.20 |

0.21 |

0.32 |

0.30 |

0.43 |

0.51 |

0.66 |

1.00 |

|||||||||||

|

11 |

mcs5 |

3.43 |

1.25 |

1 |

5 |

0.32 |

0.31 |

0.25 |

0.19 |

0.41 |

0.26 |

0.48 |

0.48 |

0.63 |

0.75 |

1.00 |

||||||||||

|

12 |

mcs6 |

3.01 |

1.49 |

1 |

5 |

0.23 |

0.32 |

0.23 |

0.28 |

0.37 |

0.29 |

0.35 |

0.42 |

0.50 |

0.54 |

0.58 |

1.00 |

|||||||||

|

13 |

mcs7 |

3.51 |

1.47 |

1 |

5 |

0.24 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

0.33 |

0.38 |

0.30 |

0.30 |

0.36 |

0.49 |

0.47 |

0.47 |

0.53 |

1.00 |

||||||||

|

14 |

fam |

3.83 |

1.51 |

1 |

5 |

-0.03 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

-0.04 |

-0.10 |

-0.06 |

-0.08 |

-0.06 |

-0.14 |

-0.06 |

1.00 |

|||||||

|

15 |

rad1 |

2.64 |

1.26 |

1 |

5 |

0.39 |

0.48 |

0.26 |

0.40 |

0.44 |

0.34 |

0.28 |

0.23 |

0.19 |

0.22 |

0.24 |

0.11 |

0.30 |

-0.04 |

1.00 |

||||||

|

16 |

rad2 |

2.55 |

1.27 |

1 |

5 |

0.26 |

0.38 |

0.29 |

0.52 |

0.58 |

0.51 |

0.31 |

0.27 |

0.24 |

0.28 |

0.32 |

0.28 |

0.38 |

-0.11 |

0.64 |

1.00 |

|||||

|

17 |

tra |

3.69 |

1.41 |

1 |

5 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

0.22 |

0.18 |

0.21 |

0.16 |

0.20 |

0.27 |

0.30 |

0.34 |

0.39 |

0.21 |

0.33 |

0.32 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

1.00 |

||||

|

18 |

lev |

46.31 |

29.18 |

0 |

100 |

0.12 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.15 |

0.04 |

0.06 |

-0.01 |

0.07 |

-0.07 |

0.01 |

-0.02 |

0.11 |

0.02 |

-0.06 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

0.05 |

1.00 |

|||

|

19 |

age |

24.11 |

12.38 |

3 |

76 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.12 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

0.27 |

0.18 |

0.14 |

0.20 |

0.23 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

-0.07 |

0.05 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

-0.14 |

1.00 |

||

|

20 |

emp |

25.91 |

41.27 |

1 |

237 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.07 |

0.19 |

0.12 |

0.09 |

0.20 |

0.16 |

0.18 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.22 |

0.13 |

-0.11 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

0.13 |

0.16 |

1.00 |

|

|

21 |

ind |

0811 |

9312 |

-0.03 |

-0.11 |

-0.04 |

-0.10 |

-0.03 |

-0.09 |

0.00 |

-0.01 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

-0.06 |

-0.12 |

-0.10 |

-0.11 |

-0.01 |

-0.13 |

-0.10 |

0.06 |

-0.18 |

0.11 |

1.00 |

||

Table 3. Definition of variables, reliability and convergent validity

|

Construct |

Indicators |

L (1) |

T |

VIF |

BQ2 |

PQ2 |

|

|

Dependent variables: |

|||||||

|

HOC: Technological innovation |

α: 0.76; ?A: 0.79; CR: 0.80 AVE: 0.80 |

||||||

|

LOC1 |

Innovation in products |

0.87 |

33.60 |

1.60 |

0.23 |

0.17 |

|

|

LOC2 |

Innovation in process |

0.92 |

78.69 |

1.60 |

0.37 |

0.34 |

|

|

LOC 1 |

α: 0.74; ?A: 0.77; CR: 0.85; AVE: 0.66 |

||||||

|

Please indicate the evolution in the last two years of… |

ipd1 |

The number of new products or services introduced per year |

0.78 |

16.71 |

1.41 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

|

ipd2 |

The pioneering character when introducing new products or services |

0.87 |

36.79 |

1.58 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

|

|

ipd3 |

The speed in response to the introduction of new products or services in the industry |

0.78 |

18.95 |

1.47 |

0.06 |

0.09 |

|

|

LOC 2 |

α: 0.83; ?A: 0.84; CR: 0.90; AVE: 0.75 |

||||||

|

Please indicate the evolution in the last two years of… |

ipc1 |

The number of changes in the processes introduced per year |

0.85 |

32.05 |

1.83 |

0.26 |

0.27 |

|

ipc2 |

The pioneering character when introducing new processes |

0.90 |

52.16 |

2.13 |

0.30 |

0.34 |

|

|

ipc3 |

The speed in response to the introduction of new processes in the industry |

0.84 |

27.84 |

1.84 |

0.19 |

0.23 |

|

|

Mediator: |

|||||||

|

Use of MCS |

α: 0.87; ?A: 0.88; CR: 0.90; AVE: 0.57 |

||||||

|

Please indicate the degree of implementation of… |

mcs1 |

ERP |

0.61 |

9.92 |

1.40 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

|

mcs2 |

Cost accounting |

0.70 |

13.97 |

1.71 |

0.15 |

0.16 |

|

|

mcs3 |

Budgeting control |

0.81 |

27.21 |

2.29 |

0.13 |

0.15 |

|

|

mcs4 |

Financial statements analysis |

0.84 |

32.60 |

2.74 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

|

|

mcs5 |

Strategical planning |

0.85 |

40.22 |

2.81 |

0.23 |

0.24 |

|

|

mcs6 |

Internal auditing |

0.75 |

19.33 |

1.77 |

0.10 |

0.12 |

|

|

mcs7 |

Quality control |

0.71 |

16.39 |

1.56 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

|

|

Treatment: |

|||||||

|

Family management |

fam |

The majority of managing positions are occupied by family members |

|||||

|

Confounders: |

|||||||

|

R&D |

α: 0.78; ?A: 0.80; CR: 0.90; AVE: 0.82 |

||||||

|

The evolution in the last two years of… |

rad1 |

R&D expenditure for new products or services |

0.89 |

43.10 |

1.71 |

||

|

rad2 |

R&D expenditure for new processes |

0.92 |

81.70 |

1.71 |

|||

|

Training |

tra |

There is a permanent and continuous training of family managers |

|||||

|

Leverage |

lev |

Total debts on total assets x 100 |

|||||

|

Age |

age |

Number of years since the firm was created |

|||||

|

Size |

emp |

Number of employees |

|||||

|

Industry |

ind |

NACE code |

. |

. |

(1) All loadings are significant at p < 0.001. L: standardized Loadings. T statistic measured through a 10,000 resampling bootstrapping procedure. VIF: Variance Inflation Factor. BQ2: Blindfolding cross validated redundancies Q2 index; PQ2: Predictive-PLS Q2 index. α: Chronbach’s Alpha; ?A: Jöreskog Rho; CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted.

Overall validation criteria: SRMR: 0.04 [99CI: 0.02 - 0.05]; dULS: 0.26 [99CI; 0.09 - 0.31]; dG: 0.131 [99CI: 0.04 - 0.132]; χ2:128.22; RMSϴ: 0.17. NFI: 0.90.

3.3. Method procedure

3.3.1. Structural equation modelling selection

We tested our model using Partial Least Squares (PLS), a variance-based Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) largely used in technology-related research (Henseler et al., 2016), family business research (Sarstedt et al., 2014) and management accounting research (Nitzl, 2016). SEM is particularly suitable for testing the proposed theoretical model because it allows for simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships between latent constructs involving mediation and accounts for measurement errors in the constructs (Zattoni et al., 2016). Traditional PLS is chosen in this study as the study uses second order models and does not have a large data set (Reinartz et al., 2009; Segarra-Moliner & Moliner-Tena, 2016). We estimated in Mode A because it performs better when sample size is moderate and indicators are collinear (Becker et al., 2013). This study uses SmartPLS 3.2.7 software (Ringle et al., 2015).

3.3.2. Mediation analyses

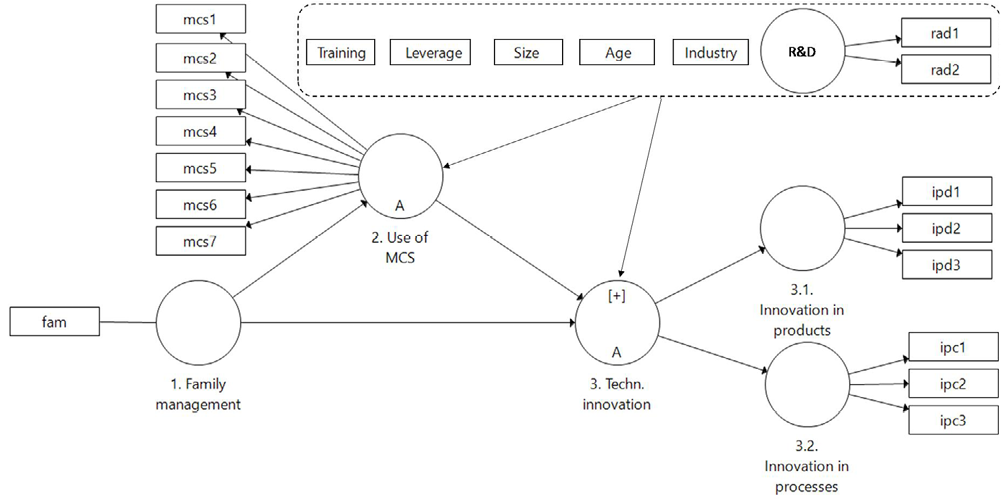

Referring to our research model in Fig. 1, H2 posits how the level of family management affects technological innovation outcomes through the use of MCS, following a path mediation model (Hayes, 2009) whereby the total effect of family management on technological innovation outcomes can be expressed as the sum of the direct and indirect effects. The latter is estimated by the product of the path coefficients for each of the paths in the mediational chain (Alwin & Hauser, 1975).

Figure 1. Proposed model

Control Variables:

We applied the bootstrapping method for testing mediation, a nonparametric resampling procedure that does not impose the assumption of normality on the sampling distribution (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), and a higher performance than the Sobel test (MacKinnon et al., 2002; 2004). Furthermore, Sobel test cannot be applied with PLS because path coefficients are not independent when computed using PLS, and PLS does not provide raw unstandardized path coefficients (Sosik et al., 2009).

3.4. Validation

Common method variance is often a concern across samples such as the one employed in this study. To test for the presence of common method variance, we followed the procedures outlined by (Podsakoff et al., 2003) and a partial correlation procedure (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). Results suggest that the bias of the common method variance is not relevant in our study. In addition, variance inflation factors (VIF) of all constructs are below its threshold of 3.3, suggesting the model is free of common method bias (Kock, 2015; Kock & Lynn, 2012). Moreover, VIF measures below the threshold of 3.3 suggest that collinearity is not a problem. Based on these results of the multicollinearity and common method variance tests, our data appears appropriate for undertaking the tests of our hypotheses.

Latent variables measured by multiple indicators were evaluated in terms of reliability, nomological validity and composition weights (Henseler, 2017). Significances were obtained by a nonparametric bootstrap procedure (10,000 repetitions). Further, we assessed the predictive ability by using the blindfolding procedure (distance-omission of 7) in order to check that cross-validated redundancies Stone-Geiser Q2 are superior to 0 (Tenenhaus & Vinzi, 2005), as well as the PLS-Predict procedure to assess the predict q2 index (10 folds and 10 repetitions).

Overall validation criteria, reliability, and convergent validity of measures are shown in Table 3. Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), unstandardized least squares discrepancy and geodesian discrepancies values are into their two-tailed 95% confidence intervals, suggesting that our theoretical model is valid (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Henseler, 2017). In addition, most of our reflective indicators load on their respective constructs more than 0.71. However, there are two items that have loadings of 0.61 and 0.70 respectively, but they can be acceptable if their rejection does not improve the model fit (Hair et al., 2017). These two items were tested and rejected, where the rejection indeed did not improve the model fit (not reported due to space limitation). Moreover, all the reliability indicators exceed their shortcuts values. SRMR value less than 0.08 reflects a good fit between our indicators and constructs (Hair et al., 2019). Discriminant validity is verified according to Fornell-Lacker Criterion and HTMT ratios (Henseler et al., 2015), as shown in Table 4, and Cross-Loadings criterion (not reported).

Table 4. Discriminant validity

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

||

|

1 |

HOC: Technological innov. |

0.90 |

· |

· |

0.53 |

0.01 |

0.26 |

0.68 |

0.03 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

|

2 |

LOC1: Innov. in products |

· |

0.81 |

0.78 |

0.37 |

0.01 |

0.59 |

0.23 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

|

3 |

LOC2: Innov. in processes |

· |

0.61 |

0.86 |

0.42 |

-0.01 |

0.73 |

0.23 |

0.04 |

0.14 |

0.13 |

0.10 |

|

4 |

Use of MCS |

0.44 |

0.44 |

0.48 |

0.75 |

-0.12 |

0.45 |

0.39 |

0.07 |

0.22 |

0.27 |

0.06 |

|

5 |

Family management |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.13 |

1.00 |

0.07 |

0.34 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.18 |

0.13 |

|

6 |

R&D |

0.23 |

0.46 |

0.60 |

0.37 |

-0.06 |

0.91 |

0.23 |

0.07 |

0.11 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

|

7 |

Training |

0.60 |

0.19 |

0.21 |

0.37 |

0.34 |

0.26 |

1.00 |

0.07 |

0.14 |

0.07 |

0.11 |

|

8 |

Leverage |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

-0.01 |

-0.05 |

-0.07 |

0.07 |

1.00 |

0.23 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

|

9 |

Age |

0.09 |

0.02 |

0.12 |

0.20 |

-0.06 |

0.10 |

0.14 |

-0.23 |

1.00 |

0.06 |

0.18 |

|

10 |

Size |

0.10 |

0.05 |

0.12 |

0.25 |

-0.18 |

0.05 |

-0.07 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

1.00 |

0.09 |

|

11 |

Industry |

-0.09 |

-0.06 |

-0.09 |

-0.06 |

-0.13 |

-0.11 |

-0.11 |

0.06 |

-0.18 |

0.09 |

1.00 |

HTMT ratio over the diagonal (cursive). Fornell-Larcker criterion: squared-root of AVE in diagonal (bold) and construct correlations below diagonal

Finally, overall predictive relevance of indicators and constructs is supported since their q2 and Q2 values are above 0 (Hair et al., 2019). Moreover, both R2 and adjusted R2 are superior to 0.10. These results indicate a well performed model. See Table 5 for details.

4. Results

4.1. Inner model results

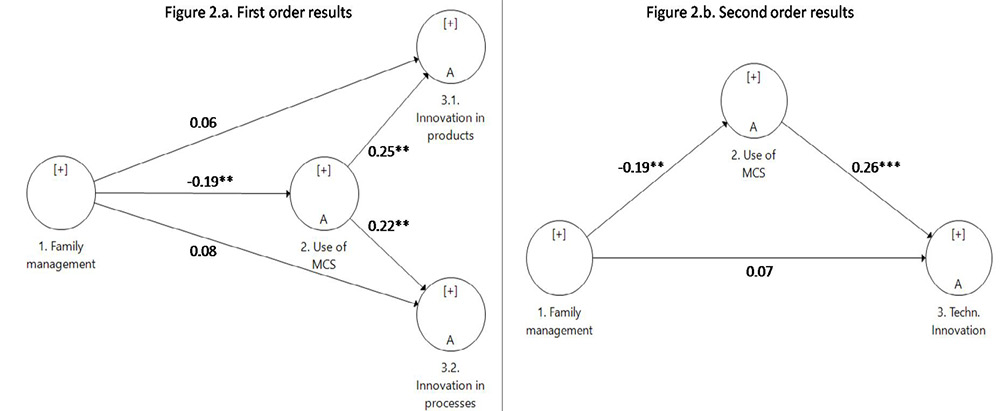

Our results suggest that family involvement in managing the business has a negative and significant impact on the use of MCS (path = - 0.19***) but it is not relevant in achieving technological innovation. Thus, H1 is not supported. Path coefficient from the use of MCS to the importance of technological innovation was positive and significant (path = 0.26***). These results are in concordance with the hypothesized mediation effect. Path coefficients and their 10,000 resampling bootstrap significance levels are reported in Table 5 and Figure 2.

Table 5. Results

|

|

Path |

T |

LO95 |

HI95 |

VIF |

f2 |

H |

Support |

|

|

High Order Model |

|||||||||

|

Family management → Use of MCS |

-0.19 |

** |

2.76 |

-0.30 |

-0.08 |

1.24 |

0.04 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Control variables |

|||||||||

|

R&D → Use of MCS |

0.25 |

*** |

3.98 |

0.14 |

0.35 |

1.10 |

0.09 |

||

|

Training → Use of MCS |

0.38 |

*** |

5.86 |

0.26 |

0.48 |

1.28 |

0.17 |

||

|

Leverage → Use of MCS |

-0.01 |

0.15 |

-0.14 |

0.11 |

1.09 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Age → Use of MCS |

0.10 |

1.59 |

-0.01 |

0.19 |

1.14 |

0.01 |

|||

|

Size → Use of MCS |

0.23 |

*** |

4.62 |

0.15 |

0.31 |

1.05 |

0.07 |

||

|

Industry → Use of MCS |

-0.01 |

0.25 |

-0.11 |

0.08 |

1.07 |

0.00 |

|||

|

(R2: 0.33; Adj. R2: 0.31; BQ2: 0.17; PQ2: 0.16) |

|||||||||

|

Fam. management → Tech. innovation |

0.07 |

1.15 |

-0.03 |

0.18 |

1.29 |

0.01 |

H1 |

N |

|

|

Use of MCS → Tech. innovation |

0.26 |

*** |

3.11 |

0.12 |

0.39 |

1.50 |

0.08 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Control variables |

|||||||||

|

R&D → Tech. innovation |

0.51 |

*** |

7.51 |

0.39 |

0.62 |

1.20 |

0.38 |

||

|

Training → Tech. innovation |

-0.01 |

0.20 |

-0.13 |

0.10 |

1.49 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Leverage → Tech. innovation |

0.07 |

1.23 |

-0.03 |

0.16 |

1.09 |

0.01 |

|||

|

Age → Tech. innovation |

0.01 |

0.15 |

-0.07 |

0.10 |

1.16 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Size → Tech. innovation |

0.02 |

0.26 |

-0.09 |

0.14 |

1.13 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Industry → Tech. innovation |

-0.01 |

0.19 |

-0.11 |

0.09 |

1.07 |

0.00 |

|||

|

(R2: 0.42; Adj. R2: 0.40; BQ2: 0.30; PQ2: 0.22) |

|||||||||

|

Low Order Model |

|||||||||

|

Fam. management → Innov. in products |

0.06 |

0.75 |

-0.07 |

0.18 |

1.29 |

0.00 |

H1 |

N |

|

|

Use of MCS → Innovation in products |

0.25 |

** |

2.83 |

0.10 |

0.39 |

1.50 |

0.06 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Control variables |

|||||||||

|

R&D → Innovation in products |

0.38 |

*** |

4.71 |

0.23 |

0.50 |

1.20 |

0.16 |

||

|

Training → Innovation in products |

0.00 |

0.03 |

-0.13 |

0.14 |

1.49 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Leverage → Innovation in products |

0.04 |

0.72 |

-0.06 |

0.14 |

1.09 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Age → Innovation in products |

-0.05 |

0.80 |

-0.14 |

0.06 |

1.16 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Size → Innovation in products |

-0.02 |

0.29 |

-0.15 |

0.11 |

1.13 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Industry → Innovation in products |

-0.01 |

0.14 |

-0.10 |

0.09 |

1.08 |

0.00 |

|||

|

(R2: 0.26 Adj. R2: 0.23; BQ2: 0.14; PQ2: -0.09) |

|||||||||

|

Fam. management → Inn. in processes |

0.08 |

1.24 |

-0.02 |

0.18 |

1.29 |

0.01 |

H1 |

N |

|

|

Use of MCS → Innovation in processes |

0.22 |

** |

2.75 |

0.09 |

0.35 |

1.50 |

0.06 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Control variables |

|||||||||

|

R&D → Innovation in processes |

0.53 |

*** |

8.29 |

0.41 |

0.62 |

1.20 |

0.40 |

||

|

Training → Innovation in processes |

-0.02 |

0.36 |

-0.13 |

0.09 |

1.49 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Leverage → Innovation in processes |

0.08 |

1.36 |

-0.02 |

0.18 |

1.09 |

0.01 |

|||

|

Age → Innovation in processes |

0.05 |

0.96 |

-0.04 |

0.14 |

1.16 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Size → Innovation in processes |

0.04 |

0.75 |

-0.05 |

0.14 |

1.13 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Industry → Innovation in processes |

-0.01 |

0.18 |

-0.11 |

0.09 |

1.08 |

0.00 |

|||

|

(R2: 0.42 Adj. R2: 0.39; BQ2: 0.28; PQ2: 0.26) |

|||||||||

Significance, T and confidence intervals are based on a 10,000 resampling bootstrapping procedure. VIF: Variance inflation factor; f2: effect size; BQ2: Cross-validated redundancies Q2 index (distance of 7); PQ2: PLS - predictive relevance q2 index (10 folds and 10 repetitions). *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

Figure 2. Results

4.2. Testing mediation effects

We applied the analytical approach described by Preacher and Hayes (2008) to test our hypothesis on mediation effect (H2). The indirect effects are specified and contrasted with the mediator (i.e., the use of MCS). We also examined the total and direct effects of family management on technological innovation outcomes. Following Chin’s (2010) suggestions, we chose the bootstrapping procedure to test the indirect effects. This generates 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) for each individual indirect effect and sequential mediation (see Table 6).

Table 6. Mediation effects

|

Path |

T |

LO95 |

HI95 |

VAF |

H |

Accept |

||

|

2nd Order Model Indirect Effects |

||||||||

|

Fam. management → MCS → Tech. innovation |

-0.05 |

* |

2.12 |

-0.10 |

-0.02 |

-1.83 |

H2 |

Y |

|

1st Order Model Indirect Effects |

||||||||

|

Fam. management → MCS → Innovation in products |

-0.05 |

* |

2.04 |

-0.09 |

-0.02 |

-4.41 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Fam. management → MCS → Innovation in processes |

-0.04 |

* |

2.00 |

-0.09 |

-0.02 |

-1.23 |

H2 |

Y |

|

Significant indirect effects for control variables: |

||||||||

|

2nd order model |

||||||||

|

R&D → MCS → Tech. innovation |

0.06 |

** |

2.38 |

0.03 |

0.12 |

|||

|

Training → MCS → Tech. innovation |

0.10 |

** |

2.82 |

0.05 |

0.16 |

|||

|

Size → MCS → Tech. innovation |

0.06 |

** |

2.48 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

|

|

|

|

1st order model |

||||||||

|

R&D → MCS → Innovation in products |

0.06 |

* |

2.23 |

0.02 |

0.12 |

|||

|

Training → MCS → Innovation in products |

0.09 |

** |

2.53 |

0.04 |

0.16 |

|||

|

Size → MCS → Innovation in products |

0.06 |

** |

2.34 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

|

|

|

|

R&D → MCS → Innovation in processes |

0.06 |

* |

2.19 |

0.02 |

0.11 |

|||

|

Training → MCS → Innovation in processes |

0.08 |

** |

2.57 |

0.04 |

0.14 |

|||

|

Size → MCS → Innovation in processes |

0.05 |

* |

2.28 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

|

|

|

Leverage, age and industry effects were insignificant (not reported). Significance, T and bias-corrected confidence intervals based on a 10,000 resampling bootstrapping procedure. VAF: indirect effect on total effect ratio. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001.

We found that indirect effect of family management on technological innovation outcomes through the use of MCS is negative and significant, supporting H2. In this sense, the negative and significant indirect effect of family management on technological innovation outcomes runs in a competitive way with positive but not significant direct effect, suggesting a mediated influence. Thus, H2 indicates that the use of MCS will mediate the relationship between family management and technological innovation outcomes. Family management significantly predicts the mediator (β = - 0.19**), while the mediator is a significant predictor of the dependent variable (β = 0.26***). Moreover, bootstrapping procedure suggests that indirect effect is significant (β = - 0.05*) (Peake & Watson, 2015; Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

4.3 Further analysis

Regarding control variables, only R&D appear to have a positive and significant direct influence on technological innovation outcomes, while R&D, training and size appear to be significant on the use of MCS. Moreover, their significant indirect effects suggest that the use of MCS mediates their influence on technological innovation outcomes. This finding is consistent with the idea that larger firms have advantages in terms of internal knowledge, financial resources, sales base, and market power, which contribute to an increase in the level of innovation (Cohen & Klepper, 1996). Finally, leverage, age and industry are not significant to the use of MCS or technological innovation outcomes.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1 Research implications

Several notable findings are obtained from this study. Firstly, our study yields notable insights for the research on innovation in FSMEs (De Massis et al., 2013). While prior research on the effect of family management on technological innovation outcomes have been very limited and mostly focused on public firms (Block et al., 2013; Maztler et al., 2015), this study, to the best of our knowledge, is among the pioneer to investigate the above relationship specifically in FSMEs. Therefore, this article renders a fruitful setting for enriching the current research, as there remains much to understand regarding MCSs in FSMEs (Moilanen, 2008; Oro & Lavarda, 2019). Our research also contributes to recent literature on heterogeneity in family firms (Chua et al., 2012; Filser et al., 2018), where we examined whether technological innovation outcomes are dependent on the level of family management. Therefore, we contribute to the existing debate regarding whether a higher level of family management is favourable or unfavourable for technological innovation outcomes.

Secondly, empirical literature on MCS has attempted to justify the choice of MCS between distinct organizations and/or its effects in the specific context of family firms (Helsen et al., 2017). However, this is among the first to consider, at the same time, family management as the main driver of the use of MCS and technological innovation as the resulting outcome. The selection of this antecedent is especially interesting in a FSME context because family managers usually exert a great influence on firm decision-making (Minichilli et al., 2010), control the organization, and have a great deal of managerial freedom (Lansberg, 1988). Particularly, our results suggest that a higher level of family member engagement in management leads to a lower degree usage of MCS. We conjecture that in FSMEs, as the level of family management increases, the more reference to family-orientated goals rather than to business objectives, which generally indicates solid feelings of trust and control, but also implies a clear disadvantage in the management control arena (Leenders & Waarts, 2003). Likewise, our results may be explained by looking into professionalization, more specifically, the formalization aspect of professionalization (Dyer, 1989). Thus, previous literature has postulated that a greater family influence leads to a lower degree of professionalization (Dekker et al., 2013), which results in a lower usage of MCS. For instance, family managers may not be aware of management control practices and methods that would facilitate the decision-making process (Rausch, 2011). With regards to the second concept aforementioned, some authors have shown that the greater the level of family influence the lower the degree of formalization, thus the lower utilization of MCS (Hielb et al., 2015). A higher level of family management will imply a greater confidence on mutual trust and clan control, relying less on formal methods of management controls (Posch & Speckbacher, 2012). Family managers usually have a solid comprehension of the business’ context and the business itself (Davis et al., 2010), which suggests that the higher the level of family management increases the lower the need to use MCS.

The findings of this study contribute to the growing literature investigating the role of MCS in innovation in FSMEs. While prior research has focused on a generally beneficial direct effect of MCS on product (Bisbe & Otley, 2004) and process innovation (Lopez-Valeiras et al., 2016), the results of this study suggest that the use of MCS have a positive mediating effect on the relationship between the level of family management and technological innovation outcomes. The level of family management influences negatively the utilization of MCS, which results in a lower chance of obtaining technological innovation outcomes. Therefore, this paper identifies one of the unfavourable effects of family managers that may explain why an increase in the level of family management, despite their undeniable positive effects on innovation, do not affect favourably and significantly on the achievement of technological innovation outcomes. Consequently, the use of MCS may provide family managers internal references in knowing the current stand of the business, hence function as a mechanism in promoting technological innovation in family-managed firms. Likewise, Duran et al. (2016) have made a call for a shift of scholarly attention to the “conversion rate” of the innovation process, where comprehending the variables that either expand or hinder the conversion of innovation input into innovation output will aid in the progression of scholarly knowledge regarding FSMEs’ competitive advantages stemming from innovation. With this study, we expand existing scholarly knowledge by recognizing the use of MCS as a great facilitator for the achievement of technological innovation in FSMEs. This is coherent with findings indicating that more active roles regarding MCS are suited to the contexts where there is notable risk regarding the effects of action (Ahrens & Chapman, 2004).

Thirdly, this study has used alternative theoretical underpinnings to the agency theory (Helsen et al., 2017), the dominant view in the research field of MCS. Moreover, building on arguments from one single existent theoretical view to clarify FSME innovation is not enough, given the complicated nature of firm-level innovation (Duran et al., 2016). Specifically, we drawn on RBV and SEW perspectives. FSMEs possess distinctive goals, capabilities, and resources. A greater emphasis on long-term orientation and non-economic objectives (Chua et al., 1999, Kotlar & De Massis 2013) foreshadow that a higher level of family management would imply the need of a more frequent implementation of MCS. However, it seems that FSMEs, being more family oriented and less professionalized, have fewer resources and capacities to implement management control methods (Dekker et al., 2013; Leenders & Waarts, 2003).

5.2. Managerial implications

From a managerial point of view, one needs to be aware that the overall effect of family management has on technological innovation outcomes is at least partially explained by the mediating role of the use of MCS. Our results suggest that if FSMEs with families actively involved in the management were able to use MCS more effectively, they would achieve greater technological innovation outcomes. To this end, FSMEs should strike a balance between increasing the skills and capabilities of the family managers and hiring external managers with outstanding competencies, expertise and experiences (Barney, 1991). Therefore, practitioners and advisor should encourage FSMEs to focus their attention on augmenting their professionalization, which in turn would generate a greater use of MCSs and thus provide the family with more information on their current stand to take risk for innovation and foster information flow within the FSME. Likewise, public and private institutions dedicated to promoting SMEs, and given the prior evidence that SMEs are generally more prone to limited resources in undertaking R&D investments (Gallego et al., 2013), should implement policies to increase professionalization, which is likely to increase technological innovation outcomes by optimizing the use of appropriate MCS.

5.3. Limitations and future research directions

Despite the contributions, this paper has some limitations, which not only represent the boundaries of its insights but also provide opportunities for future research. Firstly, despite we were not able to find evidenced of common method variance or endogeneity bias, our analysis was cross-sectional and used a single informant for our data, a common practice in prior literature. Moreover, the sample consists of only Spanish FSMEs. Future research would benefit from using different data collection methods and multiple data sources and taking a cross-country perspective testing samples from different countries and longitudinal investigations would be helpful. Recently, some studies have called for more research that explore social types of control, as management control is exercised through both results-based mechanisms and informal forms of control that work more implicitly (Helsen et al., 2017; Voss & Brettlel, 2014). Hence, future research should address how the level of family management can affect both formal and informal management control measures, and in return, its effect on technological innovation outcomes. Future studies could also analyse how professionalization at different stages of business lifecycle and generations in charge may exert a crucial influence on the relationships examined in the current study. Finally, although this article has addressed technological innovation outcomes considering both product and process innovation, future research may take a distinct approach considering the distinction between incremental and radical innovation (Covin et al., 2016).

References

Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2004). Accounting for flexibility and efficiency: a field study of management control systems in a restaurant chain. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 271-301. https://doi.org/10.1506/VJR6-RP75-7GUX-XH0X

Aiken, M., & Hage, J. (1971). The organic organization and innovation. Sociology, 5(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/003803857100500105

Aljanabi, A. R. A. (2017). The mediating role of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and technological innovation capabilities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(4), 818-841. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-07-2017-0233

Alwin, D. F., & Hauser, R. M. (1975). The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American Sociological Review, 40(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094445

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e‐business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6‐7), 493-520. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.187

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership, corporate diversification, and firm leverage. The Journal of Law and Economics, 46(2), 653-684.

Barbera, F., & Moores, K. (2013). Firm ownership and productivity: a study of family and non-family SMEs. Small Business Economics, 40(4), 953-976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9405-9

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Becker, J.-M., Rai, A., & Rigdon, E. E. (2013). Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: embracing practical relevance. International Conference on Information Systems, Milan, December 15-18.

Bedford, D. S. (2015). Management control systems across different modes of innovation: implications for firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 28, 12-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.04.003

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511435355

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82-113. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82

Berry, A. J., Coad, A. F., Haris, E. P., Otley, D. T., & Stringer, C. (2009). Emerging themes in management control: a review of recent literature. The British Accounting Review, 41(1), 709-737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2008.09.001

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2009). The choice of interactive control systems under different innovation management modes. European Accounting Review, 18(2), 371-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180902863803

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2012). Using strategic performance measurement systems for strategy formulation: does it work in dynamic environments? Management Accounting Research, 23(4), 296-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.05.002

Bisbe, J., & Otley, D. (2004). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 709-737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2003.10.010

Block, J., Miller, D., Jaskiewicz, P., & Spiegel, F. (2013). Economic and technological importance of innovations in large family and founder firms: an analysis of patent data. Family Business Review, 26(2), 180-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486513477454

Brinkerink, J., & Bammens, Y. (2018). Family influence and R&D spending in Dutch manufacturing SMEs: the role of identity and socioemotional decision considerations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(4), 588-608. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12428

Calabrò, A., Vecchiarini, M., Gast, J., Campopiano, G., De Massis, A., & Kraus, S. (2019). Innovation in family firms: a systematic literature review and guidance for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(3), 317-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12192

Casillas, J. C., & Moreno, A. M. (2010). The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth: the moderating role of family involvement. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 22(3-4), 265-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985621003726135