European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 111-129

Managerial Capabilities in the Family Tourist Business: Is Professionalization the Key to Their Development?

César Camisóna, Alba Puig-Deniab*, Beatriz Forésb, Montserrat Boronat-Navarrob,

José María Fernández-Yáñezb

a Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain

b Universitat Jaume I, Castellón, Spain

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M1, Z3

KEYWORDS

Family business, Governance structure Management capabilities, Professionalization, Tourism sector

CÓDIGOS JEL

M1, Z3

PALABRAS CLAVE

Capacidades directivas, Empresa familiar, Estructura de gobierno, Profesionalización, Sector turístico

Abstract The main objective of this work is to analyze the elements of the particular governance structure of the family business and the involvement of the family in the business in order to identify their effects on managerial capabilities. Furthermore, the study examines the role of professionalization in this type of company as a moderating variable. To that end, the analysis draws on the resource-based view and agency theory. The empirical study is carried out using multiple linear regression analysis on a sample of 591 Spanish tourism companies. The results show that many of the specific characteristics of the family business have a negative effect on their managerial capabilities, preventing their proper development. However, the professionalization of the head of the family business contributes to alleviating these problems, facilitating the development of said capabilities in the family business.

Las capacidades directivas en la empresa familiar turística: ¿Es la profesionalización la clave para su desarrollo?

Resumen Este trabajo tiene como principal objetivo analizar los elementos de la particular estructura de gobierno de la empresa familiar y la implicación de la familia en el negocio para comprobar sus efectos sobre las capacidades directivas. Asimismo, se estudia la profesionalización en este tipo de empresas como variable moderadora. Para abordar este análisis, se toma como base el enfoque basado en recursos y capacidades y la teoría de la agencia. El estudio empírico se lleva a cabo sobre una base de 591 empresas turísticas españolas mediante un análisis de regresión lineal múltiple. Los resultados demuestran que muchas de las características peculiares de la empresa familiar ejercen un efecto negativo sobre sus capacidades directivas, impidiendo su correcto desarrollo. Sin embargo, la profesionalización del máximo responsable de la empresa familiar contribuiría a paliar dichos problemas, facilitando el desarrollo de dichas capacidades en la empresa familiar.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10794

Copyright 2021: César Camisón, Alba Puig-Denia, Beatriz Forés, Montserrat Boronat-Navarro, José María Fernández-Yáñez

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: puiga@uji.es

1. Introduction

The interaction of family and business determines the relationships established within the family business. This combination inevitably gives rise to the special identity that sets family businesses apart from non-family ones, and that takes shape in the particular governance, ownership and control structure in these companies. In turn, the specific structure in the family business largely determines its competitive behavior, its continuity and, ultimately, its success or failure.

Among the key aspects for the success of the company are the managerial capabilities, since they are essential for the good management and performance of the company, as well as for the development and use of the rest of the company’s resources and capabilities (e.g., Carmeli & Tishler, 2006; Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Hitt & Ireland, 1985; Keil et al., 2017; Mahoney, 1995; Martínez et al., 2010). Despite their importance, there are very few studies that analyze managerial capabilities within the family business (Garcés-Galdeano et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2019; Salvato et al., 2012).

The first objective of this work is therefore to analyze the governance structure in the family business and the involvement of the family in the business in order to understand what aspects of this type of business contribute to or delay the development of managerial capabilities in the family tourism business. Previous research on the family business as well as specialized organizations in this field, such as the Spanish Family Business Institute, highlight the need for professionalization in order to achieve success in the family business, relating it in many cases to succession planning and the transition from an informal management style to a more formal one (Benavides et al., 2011). Therefore, the second objective of this work is to study whether the professionalization of the head of the company moderates the influence of the different elements of the structure of the family business on their development of managerial capabilities.

To address these issues, this study draws on the resource-based view (RBV) and agency theory. The empirical analysis relies on a database of 591 family tourism businesses and the hypotheses are tested using a multiple linear regression model.

2. Theoretical Approach

In this study, we apply two different approaches to examine the different elements of the family business; namely, the RBV and agency theory. Both approaches have been widely used to analyze issues related to the family business (Astrachan, 2010; Basco, 2006; Chrisman et al., 2003, 2005). On the one hand, the RBV emphasizes the importance of the specific capabilities and resources of each company as determinants of its ability to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. On the other hand, there has been growing interest in aspects related to ownership, control, owner orientation, property dilution, and governance mechanisms that regulate the effect of separating ownership and control. Agency theory has been the predominant approach used to address these issues in the context of the family business (Astrachan, 2010). These two approaches thus lay the foundations to analyze the differential characteristics of the family business and their influence on managerial capabilities.

2.1. Family involvement and governance structure in the family business

The family business governance structure can be studied through the lens of a number of different elements. In our case, we focus on the degree of family involvement in this governance structure and on aspects related to generational succession and family development, as proposed below.

2.1.1. Succession in the family business

The succession process in ownership and control structures is key for many family businesses that seek to retain control over the business in the hands of the family (Salvato et al., 2012; Westhead et al., 2001). The survival of the company through the generations often depends on its ability to enter new markets and its ability to revitalize itself (Richards et al., 2019; Ward, 1987). Throughout this process, appropriately developed managerial capabilities are needed to efficiently manage the company and generate competitive advantages that keep it in the market.

Most founders of a family business want to maintain family control and protect its legacy (e.g., Astrachan et al., 2002; Duran et al., 2016; Jaskiewicz et al., 2015; Salvato et al., 2012; Sciascia et al., 2014). This aspiration may sometimes be due to the propensity towards nepotism in family businesses (Khanin et al., 2019), although some research (Burkart et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003) alludes to more rational reasons in a number of specific situations: for example, cases where the current legal system provides low protection for shareholders such that the separation between ownership and control would be inefficient; the family gains reputational and non-pecuniary benefits if it maintains leadership within the family; or when companies’ competitive advantages are based on idiosyncratic knowledge that can only be efficiently transferred to very reliable family or close non-family members.

Founders of the family business tend to have an entrepreneurial character, evident when they recognize and exploit the opportunity to create a business (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003); however, over time, they often become more conservative and lose that entrepreneurial orientation (Dertouzos et al., 1989; Röd, 2016; Salvato, 2004; Zahra et al., 2004). The founder’s desire to keep the business in the hands of the family and preserve the family wealth can lead to an aversion to risk and change (Carnes & Ireland, 2013; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006).

Furthermore, even if the first generation of the family business had an entrepreneurial character and efficient managerial capabilities, this does not necessarily mean that subsequent generations will have the same characteristics. Evidence shows that future generations of the family are often unclear about their professional skills, talents, goals, and interests (Eckrich & Loughead, 1996). This confusion may be due, according to some authors (García-Álvarez et al., 2002), to socialization processes aimed at instilling in potential successors a sense of obligation to pursue a professional career within the family business. Similarly, some potential successors may not have the right skills and knowledge to continue the family business, which can lead to its failure. Conversely, the prepared successors may decide they want to pursue their own careers and thus may be reluctant to join the family business (Birley et al., 1999; Stavrou & Swiercz, 1999), which can lead to a situation where less-skilled successors take charge of the business.

In the specific case of tourist activities, many founders are motivated to create a company for reasons related to a specific lifestyle, with the preference for certain locations or leisure activities (Ateljevic & Doorne, 2000; Getz & Carlsen, 2000; Peters et al., 2019); however, subsequent generations may not necessarily share the same interests.

Some authors suggest that while the first generation should possess the technical or entrepreneurial knowledge necessary to start a business, subsequent generations would need to focus on maintaining and enhancing the growth and success of the business (McConaughy et al., 1999). The transfer of tacit knowledge from generation to generation is also seen as essential to preserve the continuity of the company and achieve and maintain competitive advantages (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Cucculelli et al., 2016; De Massis et al., 2015). In any case, the key to ensuring the survival and continuity of the family business seems to lie in the ability to maintain an entrepreneurial and active attitude that continually revitalizes the business.

If the company succeeds in surviving through to the second generation, the successors must be in charge of revitalizing it, to which end they must have the necessary management skills (Broekart et al., 2016). However, in many cases, the transition of the company to the next generation occurs regardless of whether the successors are qualified to take responsibility for the business. Thus, the new generation will not always master the required management methods and principles and their entrepreneurial and leadership skills will not necessarily be sufficiently well developed.

Since few companies manage the transition to the third and subsequent generations (according to data from the Spanish Family Business Institute), we focus here on first- and second-generation companies. Thus, although first-generation companies contribute to the development of managerial capabilities due to their entrepreneurial orientations, the transfer of the business to the second generation hinders the promotion and improvement of these capabilities. Based on this idea, we propose our first two hypotheses:

H1. The first generation of the family business positively affects the development of managerial capabilities.

H2. The second generation of the family business negatively affects the development of managerial capabilities.

2.1.2. Non-managerial family employees

Focusing on non-managerial employees, family owners tend to prefer to employ family members in their businesses (Barach et al., 1988; Cirillo et al., 2019; Cromie et al., 1995; Dyer & Handler, 1994). Furthermore, it is difficult for small businesses to attract qualified non-family personnel, since they will often feel uncomfortable interfering with family structures (Tan & Zutshi, 2001; Terberger, 1998). However, the hiring of non-managerial family employees is frequently based more on blood ties than on the real capabilities or merits of the employee (Astrachan, 2010), pointing to nepotistic practices (Firfiray et al., 2018). Hiring family members regardless of their qualifications or capacity for the position can cause serious problems for the company and for the development of managerial capabilities. It seems clear that each position should be filled by the best possible candidate, whether this is a family member or not (Hall & Nordqvist, 2008), in order to ensure the best results for the business. Hiring based on other criteria may suggest unstrategic behavior, based more on personal rather than business interests. These personal interests lead to difficulties when it comes to deploying efficient managerial capabilities, curbing economic rationality and diverting the focus away from the ultimate purpose of the company.

Furthermore, the hiring of family employees based on anything other than business criteria can generate conflicts in the family-business sphere. Non-family employees may feel that they are being treated unfairly (Schulze et al., 2002) when they perceive preferential attitudes towards family employees. In this sense, altruistic behaviors towards the family can lead to an inability to sanction or fire family employees who deserve it (Schulze et al., 2003); in the same way, this altruistic behavior entails an equitable treatment of different members of the same family, even when their contribution is not equal (Schulze et al., 2002). At the same time, having too many family members involved in the business opens the door for conflicts generated within the family to be transferred to the scope of the company. These aspects have a negative influence on managerial capabilities that hinders the objectivity and acceptance of diverse ideas and the decision-making process.

From another point of view, interests related to the welfare of the family can make managers succumb to requests from family employees, thus preventing the exercise of effective leadership. Also, employees who are family members may adopt altruistic behaviors due to their family membership, believing themselves to be working for the family well-being and wealth, as part owners of the business (Schulze et al., 2002). In so doing, they may create confusion regarding roles, to some extent coercing the managerial work (family or non-family). In companies where a large number of employees are family members, the altruistic behavior of preserving family well-being together with the fear of losing their job in the family business can lead to a greater aversion to risk and uncertainty, making it much more difficult for managers to adopt and foster entrepreneurial attitudes to support change.

Likewise, the presence of family employees in the company leads to the emergence of much more informal structures and agreements. Altruism fosters an increase in communication and cooperation in the family business that encourages this use of more informal agreements (Daily & Dollinger, 1992). Although to a certain degree it can be advantageous, poorly defined and informal structures mean that the roles that correspond to family employees and others who occupy a higher level in the company are not always clearly differentiated; thus, family agents tend to take advantage of the manager when the responsibilities of the manager and the family agent overlap (Lindbeck & Weibull, 1988), reducing the effectiveness of management supervision. These situations generate problems for the management in terms of coordinating and exercising real leadership, at the same time as they pose obstacles when it comes to adopting more strategic visions where the interests of the company prevail over individual interests. Likewise, the unstructured nature of these companies is a barrier to attracting professional managers (family members or external) who actually have the right training or experience for the position (Fernández & Nieto, 2005), which directly affects their managerial capabilities.

These considerations lead us to conclude that high levels of non-managerial family involvement can make it difficult to promote certain aspects such as leadership, strategic vision, support for change, acceptance of diverse opinions in cases of conflict, application of purely business principles or fostering an entrepreneurial spirit, hindering the development of managerial capabilities. Therefore, in our third hypothesis we posit that the following effect occurs:

H3. The greater the non-managerial family involvement in the family business, the less the development of effective managerial capabilities.

2.1.3. Family managers

Many of the abovementioned aspects regarding non-managerial family involvement can apply to family members who hold managerial positions. If family managers feel morally compelled to comply with obligations in both the business sphere and the family sphere, this can generate confusion between the ties of affection to the family and contractual ties to the company (Gallo, 1995). Thus, aspects related to altruism, overlapping roles or the appearance of conflicts from the perspective of managerial family involvement are expected to have similar effects on managerial capabilities as those suggested for the case of non-managerial family employees.

The owner of the family business tends to hire family managers in order to retain control of the company (Brunninge & Nordqvist, 2004; Carnes & Ireland, 2013). This desire for control favors the proliferation of family members in high positions. The presence of independent managers is proposed in the literature as a factor that can contribute to reducing agency costs (Samara & Berbegal-Mirabent, 2018). On the contrary, although it is argued that the coincidence of ownership and control can reduce agency costs due to the overlapping interests, hiring too many relatives in these positions can raise questions because while it is difficult to find a good manager, it is even more difficult to find a good manager from inside the family (Zuñiga & Sacristán, 2009). In these cases, the selection and remuneration are based more on family ties than on the professional experience or managerial competence of the candidates (Fukuyama, 1995; Khanin et al., 2019; Le Breton-Miller et al., 2004; Ng et al., 2019), which leads to low-qualified managers who are ill-prepared to properly manage the company.

Another factor that encourages the hiring of family managers is the difficulty family businesses face in attracting sufficiently qualified external managers (Carney, 2005; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). This is due, on the one hand, to the unstructured nature of these companies; and on the other, to the difficulties that non-family managers may encounter in developing a professional career in competition with family members, given that the latter are favored by incentive and promotion systems (James, 1999; Lansberg, 1983).

In any case, filling too many managerial positions with family members has negative repercussions when it comes to stimulating the development and improvement of managerial capabilities. There are a number of different reasons for this. First, although it is possible that a family member may possess the necessary attitude and knowledge, a reliance on family ties to promote or hire managers (Khanin et al., 2019; Westhead, 1997) leads to a large number of family members in important positions who will tend to be poorly qualified, unaware of appropriate methods and instruments for business management, and/or will lack strategic and entrepreneurial attitudes, which are essential for forging the appropriate managerial capabilities (Khanin et al. , 2019). Second, given that family managers inevitably try to achieve a better future for the family through the business (Chua et al., 1999; Sharma et al., 1997), as the number of family managers increases, the line between family and business becomes less clear and the prevalence of family and business interests hinders the development of a strategic conception of the business and effective leadership (Khanin et al., 2019). Third, an excessive degree of family involvement in managerial positions can spark conflicts (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006), preventing objective decision-making and the acceptance of diverse opinions.

Given that people tend to be more prudent with their own money and belongings than with those of other people (Carney, 2005), the more family managers there are, the more difficult they will find it to promote pro-change attitudes, with managers themselves being reluctant to change or to take advantage of opportunities that may pose a certain risk to the wealth and well-being of the family (Daspit et al., 2019). In this respect, family members often feel emotionally attached to the organization (Miller et al., 2003), which prevents behaviors that endanger the company and the position they occupy within it; indeed, aversion to risk associated with high levels of ownership concentration hinders entrepreneurial orientation (Daspit et al., 2019; Diéguez-Soto et al., 2016; Schulze et al., 2002).

Therefore, these aspects, along with some of those discussed above for non-managerial family employees, suggest that excessive managerial family involvement in the company can generate problems. The requirements of the family and business areas differ considerably (Lansberg, 1983; Leach, 1993), so the family’s operating framework is not always appropriate for running the business (Galve, 2002). Furthermore, Garcés-Galdeano et al. (2016) found in their study that family management and ownership are negatively associated with managerial capabilities.

To sum up, limiting decision-making roles to a restricted group of people—in this case, family members—prevents the development of the managerial capabilities that are so important for the company (Carney, 2005; Ng et al., 2019; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). Therefore, we propose our fourth hypothesis as follows:

H4. The greater the family managerial involvement in the family business, the less the development of effective managerial capabilities.

2.1.4. Corporate governance bodies: the board of directors

As a possible solution to the problems arising from the interaction between the family, business and ownership systems, family businesses have at their disposal certain mechanisms and bodies that can help them to manage the business more efficiently. Some of these are specific to the family business and will be discussed in the following subsection. However, there are other bodies which, although they are not specific to family business, have specific features within this type of company and must be adapted to fulfil their functions more effectively (Sánchez-Crespo et al., 2005). One of the most notable of these bodies, due to its multiple functions in the context of family business, is the board of directors (Dekker et al., 2015).

The board of directors is the highest governing body of the company, with the exception of certain matters assigned by law to the general shareholders’ meeting. In any company, its basic functions involve the guidance, supervision and validation of corporate decisions and oversight of the management team. The board members’ goal is to maximize the value of the shares without detriment to the ethical and exhaustive respect of other contracts with customers, suppliers and employees (Chang & Shim, 2015; Dekker et al., 2015; Galve, 2002).

Experts on the subject suggest certain guidelines for optimizing board composition and structure (Galve, 2002; Howorth et al., 2016). Thus, regardless of whether the director is a family member or not, the requirements for board membership are managerial ability and/or competence, loyalty to shareholders and other stakeholders, knowledge of business and the company itself, family values and having no ownership interest in the company. Therefore, family directors should be sufficiently prepared to contribute to meetings, or at least not hinder them. In addition, it is recommended that a certain number of external directors be included to provide objectivity and to look after the interest of the company beyond family motivations.

Therefore, while a certain degree of family involvement in the board of directors allows the objectives of the company and the family to be aligned (Barontini & Caprio, 2006; Jaskiewicz & Klein, 2007; Lane et al., 2006), a high degree of family involvement may lead to family interests being served at the expense of the company and, thus, the expropriation of minority shareholders (Braun & Sharma, 2007). In this regard, some family involvement in the board allows family directors to be engaged in interests related to the company and not only those concerning the family, helping to boost managerial capabilities through the acceptance of diverse opinions and the adoption of more strategic visions. Moreover, by incorporating non-family members the company gains access to valuable experience and knowledge and can also consult more objective opinions. Conversely, an all-family board may hinder the proper development of managerial capabilities by interfering with business interests and preventing actions that could promote change or involve some degree of risk.

The absence of a board of directors can also be an obstacle to the promotion of managerial capabilities, as there is no body to ensure that the interests of all those involved in the company are met, or to encourage more formal and effective communication, the clear definition of the company’s objectives and values, or its strategic orientation.

For these reasons, we set out below a number of hypotheses arising from the above discussion:

H5. The lack of a board of directors hinders the development of managerial capabilities in the family business.

H6. A certain degree of family involvement in the board of directors favors the development of managerial capabilities in the family business.

H7. A board of directors made up exclusively of family members hinders the development of managerial capabilities in the family business.

2.1.5. Governance bodies and mechanisms specific to the family business

The literature suggests that governance bodies in the family business are needed to reduce agency problems such as information asymmetries between different stakeholders or differences in objectives (Chrisman et al., 2018). Although there are multiple instruments that can be considered, we focus here on some of the most important; namely, the family council, the family protocol and some rules that regulate aspects related to the family-ownership-business interaction.

The family council is, together with the family assembly, one of the governing bodies related to the entrepreneurial family. While the family assembly is an informative and non-decision-making body made up of all family members, the family council has a decision-making role (Galve, 2002) and, unlike the family assembly, is a permanent structure. Specifically, the family council is responsible for regulating the functioning of the business family and its relations with the company, discussing both present problems and future projects; it also contributes to strengthening and keeping alive family values and history, preserving its unity and harmony (Blumentritt et al., 2007). Its composition, structure and functions will vary according to the specific characteristics of each company, although it is recommended that board members be chosen on the basis of their ability to perform the functions entrusted to them (Lansberg & Varela, 2001).

Another important mechanism is the family protocol, which is considered one of the most important formal instruments of governance. It is the instrument that allows the family and the company to self-regulate in order to establish a context with stable rules that are known to all, with the aim of preventing conflicts and promoting the long-term continuity of the company in hands of the owner family (Sánchez-Crespo et al., 2005). There are a series of points that are usually included in the family protocol and which are related to the implementation of structure, composition and functioning of the governing bodies; rules and principles corresponding to the management of human resources; guidelines for the distribution of capital and the transfer and valuation of shares; dividend policy; and rules for revising the protocol (Galve, 2002). The protocol should be drawn up when there are no conflicts in the family business, in order to prevent them from happening. It will be far more complicated to develop when there are conflicts or problems occurring.

Finally, the establishment of certain rules, whether verbal or written, is also important for the family business. Thus, the family business can promote, for instance, rules related to the incorporation of family members in the company, remuneration and other aspects of the work of family members; rules on management succession and the transfer of ownership; rules on the distribution of power between branches of the family; or rules on aspects such as the company structure or the sale of its shareholding by family shareholders. These rules help ensure more objective and clearer decision-making, facilitating more impartial behavior in the management of the company and providing tools on key issues such as management succession.

The use of one or more of these mechanisms limits or prevents certain conflicts arising from overlapping roles between the business and the family, especially as more complex organizational forms emerge. In turn, this can have significant impact on economic performance (Arteaga et al., 2017). Problems arising from contradictions between family and business rules, or the desire to retain family control of the business, can lead to conflicts that affect the business and, in this case, managerial capabilities. This can be prevented by the use of said mechanisms to ensure the appropriate planning and management of family-ownership-company relations. In light of all of this, our eighth hypothesis posits that the appropriate use of this type of instrument enables the family business to improve its managerial capabilities:

H8. The use of specific family business governance bodies and mechanisms favors the development of managerial capabilities.

2.2. Professionalization of the head of the family business. Implications for its governance structure

Professionalization is one of the most interesting aspects in the field of family business (Daspit et al., 2019; Dekker et al., 2015; Lien & Li, 2014; Madison et al., 2018; Sandu, 2019). The level of education, being a reflection of the knowledge and skills an individual possesses, may be positively related to the ability to make strategic choices according to the demands of the environment (Wiersema & Bantel, 1992) or the propensity to generate and implement creative solutions to the firm’s problems (Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Diéguez-Soto et al., 2016). Although its influence should be positive, it will not necessarily be significant; that is, the professionalization of the family business reflected through the qualifications of the head of the business does not necessarily have a significant effect on managerial capabilities if it does not succeed in modifying and influencing the values and structure of the family business. However, we posit the following hypothesis in order to test its effect:

H9. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, this has a positive impact on managerial capabilities.

Furthermore, there are certain features that stem from the professionalization of the head of the family business that we believe will enable him/her to modify certain elements of the structure so that they become advantageous for the development of managerial capabilities.

Regarding generational criteria, aspects related to this issue are closely linked to the professionalization of the person in charge of the family business. Thus, a professionally-qualified head of first-generation companies can help ensure the professionalization of the company, and the same is true for second-generation companies.

Therefore, regardless of the dominant generation in the business, if the head is sufficiently qualified to address the aspects of the family business that typically have a negative effect, managerial capabilities can be adequately developed. In this regard, a professionally-qualified business head is able to transmit entrepreneurial values, transfer tacit knowledge and revitalize the company, which are crucial for its survival (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Ward, 1987). Hence, the following hypotheses refer to this effect:

H10. If the head of a first-generation family business has a professional qualification, this has a positive influence on the development of managerial capabilities.

H11. If the head of a second-generation family business has a professional qualification, this has a positive influence on the development of managerial capabilities.

The professionalization of the business also has an impact on family involvement in other job levels: on the one hand, professionalized companies tend to be more cautious when choosing both their employees and their managers, and will avoid bringing too many family members into the company; on the other hand, even if they do hire a large number of family members, they will ensure that they are really qualified for the position. In this sense, just as highly-qualified managers tend to surround themselves with more qualified employees (Boling et al., 2016; Fernández et al., 2006), a professionalized company makes greater efforts to recruit employees fairly, based on objective and justified reasons, selecting those candidates who are best suited for each position, regardless of whether or not they are family members (Hall & Nordqvist, 2008).

Therefore, in professionalized companies a higher degree of family involvement does not necessarily have a negative impact, since employees and managers are selected on the basis of their knowledge and experience and not for reasons of family affinity. Moreover, in such cases, higher degrees of family involvement may even favor managerial capabilities: not only will family employees be suitable for the job, but as family members, their culture and values will also be similar to those of the company, and their conduct will therefore be aligned with the interests of the business. In this vein, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

H12. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a higher degree of non-managerial family involvement contributes positively to the development of managerial capabilities.

H13. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a higher degree of family involvement in management contributes positively to the development of managerial capabilities.

The professionalization of the family business also means that members of the board of directors tend to be capable of performing their role. In such cases, the presence of family board members—who may or may not hold managerial positions—does not necessarily have a negative influence on the promotion of managerial capabilities. Thus, even if there are some family directors with no links other than ownership, who are defending their personal interests, a high degree of professionalization in the family business prevents personal interests from overriding those of the company and helps ensure the interests of all groups are represented on the board.

Nevertheless, while a board composed entirely of family members may not necessarily have a strong negative effect, nor does it necessarily improve managerial capabilities. That is, while it may not prevent the widespread adoption of a strategic vision, it does not facilitate it. Thus, a professionally-qualified business head will be able to spread business values throughout the organization, even if he or she does not have strong support from the board of directors; however, some involvement of external directors is needed to ensure greater objectivity.

Moreover, professionalized companies also tend to be fairly complex, thus requiring a board of directors. The absence of such a governance body may be an even greater obstacle to the development of managerial capabilities in complex organizations. While it is assumed that the top management can put in place other types of mechanisms, the lack of a board of directors is an obstacle to more formal and effective communications. Thus, even professionalization will not solve the problems arising from the absence of this body, meaning it will have a negative impact on managerial capabilities. In light of these arguments, we suggest the following hypotheses:

H14. Even when the head of the family business has a professional qualification, the lack of a board of directors is an obstacle to the development of managerial capabilities in the family business.

H15. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a certain degree of family involvement in the board of directors continues to be beneficial for the development of managerial capabilities.

H16. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a board of directors composed entirely of family members has a negative influence on the development of managerial capabilities.

Finally, with regard to the governance bodies and mechanisms of the family business, we have already indicated that they have a positive effect on managerial capabilities. Along the same lines, we therefore present our last hypothesis as follows:

H17. The use of governance bodies and mechanisms in family businesses where the head has a professional qualification favors the development of managerial capabilities.

3. Methodology

3.1. Database

The database we use consists of family businesses operating in the Spanish tourism industry with more than three employees. The initial data used to create the database were obtained from a questionnaire, with different sections related to the analysis of the competitiveness of the tourism company, conducted in 2009 through personal interviews with the CEO or general manager. We applied a modified version of Dillman’s Total Design Method (1978) to mitigate the problems associated with questionnaires as a data collection method, and to improve the response rate and the quality of the information. The interviews were conducted by a company specializing in tourism market research, in close collaboration with the research team responsible for the project. The interviews were administered to both non-family businesses and family businesses, although for the present study only the latter are included. Thus, the database for this study is made up of a total of 591 family tourism businesses. Companies with fewer than three employees were also eliminated as they made it very difficult to study some of the elements included in our analysis. The fieldwork was carried out from December 2009 to March 2010. We also added data from the Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos (SABI), a database managed by Bureau Van Dijk and Informa D&B, S.A., to complete the financial information from 2008 to 2016.

3.2. Variables measurement

Managerial capabilities, the dependent variable in this study, have been measured using items related to managers’ strategic vision and their ability to support change and learning, encouragement of the spirit of dialogue and acceptance of diverse opinions, entrepreneurial orientation, managerial expertise in the principles and methods of business management, and effective leadership. This variable has been introduced as the arithmetic mean of these items (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.945). The items that make up this variable have been measured through seven-point Likert-type scales reflecting managers’ perception of their strength in managerial capabilities compared to industry competitors (1 = “much worse”; 2 = “worse”; 3 = “slightly worse”; 4 = “average”; 5 = “slightly better”; 6 = “better”; 7 = “much better”).

The independent variables have been measured in different ways. In order to capture aspects related to the dominant generation in the family business, two dichotomous variables have been introduced: one indicates “first-generation family businesses” and the other “second-generation family businesses”, with the reference variable being “third generation or more family businesses”.

Regarding “non-managerial family involvement”, this objective variable captures the degree to which the family participates in the company in positions not related to management. It is measured as non-managerial family involvement as a percentage of total non-managerial employees and is entered in the model in logarithmic form in order to address possible problems related to heterogeneous variances or a wide range of values in the variable.

Following the same procedure, the variable “managerial family involvement” captures the degree to which family members participate in managerial positions in the business (general management, department directors and division directors). This variable shows the family managers as a percentage of the total managerial positions and has also been introduced in its logarithmic form.

Regarding the aspects related to the board of directors, three dichotomous variables have been introduced that refer to the following situations: “there is no board of directors”, “some family members sit on the board of directors” and “all the members of the board of directors are family members”, with the reference variable being “no family members sit on the board of directors”. The variable “there is no board of directors” takes a value of 1 when there is no such body and 0 otherwise. The variable “some family members sit on the board of directors” takes a value of 1 for those cases in which some but not all of the board members are family members and 0 otherwise. The variable “all members of the board of directors are family members” takes a value of 1 for cases in which 100% of the directors are family members and 0 otherwise. For our study, we have considered it more appropriate to use dichotomous rather than continuous variables as there may be many companies that do not have a board of directors and this approach allows their inclusion.

With reference to the “use of governance mechanisms specific to family businesses” we have introduced this effect as a dichotomous variable where 1 indicates that the company makes use of one or more of the instruments explained in the corresponding section, either verbally or in writing (family council, family protocol, norms for the incorporation of family members, succession rules, etc.), while the value 0 indicates that the company does not use any instrument of this type.

The explanatory variable “family business head’s qualifications” has also been introduced as a dichotomous variable, in which the value 1 indicates that the head of the family business has completed postgraduate studies in tourism, strategic management or similar.

Furthermore, four control variables have been introduced in the model. They capture the “age” of the company, measured as the number of years it has been in operation; the “training effort”, included as a dichotomous variable in which 1 indicates that the company develops training plans and 0 that it does not; the “environmental attractiveness”, operationalized through the arithmetic mean of 11 items related to the advantages offered by the environment (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.701); and the “tourist destination attractiveness” measured in a similar way to the previous one, but composed of 19 items that capture the benefits in training, experience, etc., offered by the tourist destination where the company competes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.922).

3.3. Analysis technique

To test the aforementioned hypotheses, hierarchical regression analysis is carried out using SPSS 21.0. Before entering the moderating effects, the main variables are mean centered to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken et al., 1991; Cohen et al., 2003). The results are statistically robust, as compliance with the basic assumptions for regression analysis was verified by an analysis of the residuals and of other graphs and statistics provided by the program.

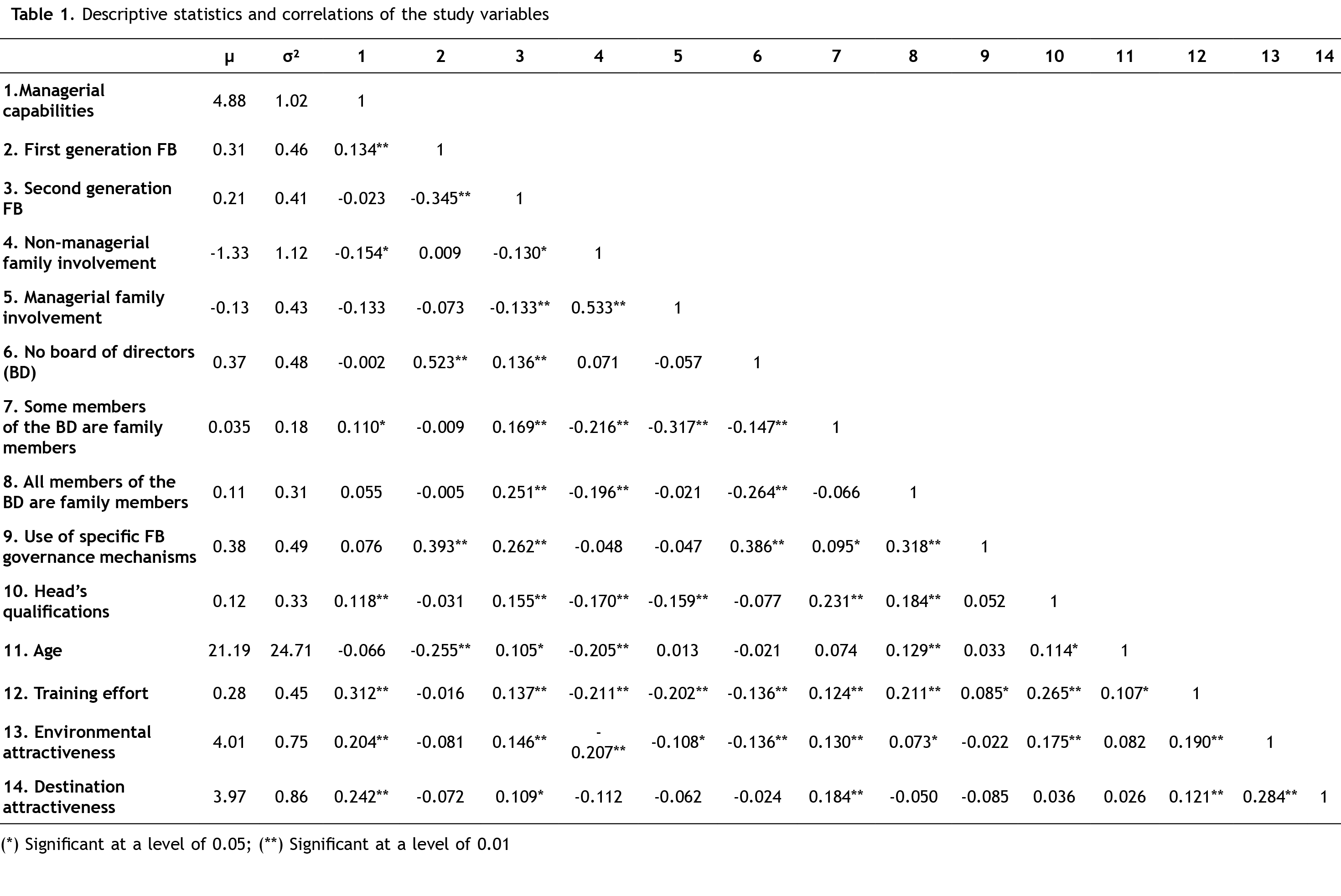

The following table presents the descriptive statistics and the correlations of the study variables. The levels of correlation between the variables are low: they are all below 0.6 (see Table 1) (Churchill, 1979), thus confirming the discriminant validity of the model. The convergent validity of the dependent variable was also verified with objective internal (concurrent validity) and external (predictive validity) measures of the firm. Specifically, concurrent validity was tested by verifying whether the measure of managerial capabilities based on the manager’s perceptions was convergent with the objective measure of R&D expenses (developed with firm’s internal employees). The Pearson correlation coefficient between the two variables was positive (r = 0.104) and statistically significant (p < 0.05). Predictive validity was verified by means of the correlation between managerial capabilities and economic performance. Performance was operationalized through the return on assets taken from the annual accounts for 2010 compiled in the SABI database. The results show positive correlations (p < 0.01) between environmental performance and economic performance (r = 0.151).

4. Results and Discusion

4.1. Overview of the model

The estimated results are statistically robust, as it has been checked that the basic assumptions of linear regression (linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, normality, and non-collinearity) have been met, by analyzing the residuals and other graphs and statistics provided by the SPSS program.

After verifying these requirements, the model has been estimated. In order to introduce the moderating effect of the qualifications of the head of the family business, three different models have been tested to see if the R2 increases when the effect is introduced. We apply the procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test the moderating effect by estimating different regressions, an approach used in other studies on this topic. In model 1 only the effect of the control variables is included. Model 2 includes all the explanatory variables, while model 3 considers the interaction terms between the variables.

Table 2 displays the results of estimating the model for each of the proposed relationships. The significance of the F statistic is acceptable for all the estimated models. As can be seen, the explanatory power of the models increases first when the explanatory variables are introduced, and then when the moderating effects are introduced. In the case of the complete model with the direct and moderating effects, the adjusted R2 shows an explanatory power for managerial capabilities of 26.5%.

Table 2. R2 for the different models

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

|

Increase in the R2 |

0.176 |

0.098 |

0.097 |

|

R2 |

0.176 |

0.274 |

0.371 |

|

R2 Adjusted |

0.166 |

0.203 |

0.265 |

|

F (Sig.) |

16.801 (0.000) |

3.868 (0.000) |

3.507 (0.000) |

Table 3 presents the results of the regression.

Table 3. Regression results of the governance factors of the family business on managerial capabilities

|

B |

Standard error |

β |

t |

Sig. |

|

|

Constant |

2.959 |

0.467 |

-- |

6.329 |

0.000 |

|

Control Variables |

|||||

|

Age |

-0.005 |

0.004 |

-0.138 |

-1.153 |

0.251 |

|

Training effort |

0.960 |

0.191 |

0.422 |

5.030 |

0.000 |

|

Environmental attractiveness |

0.275 |

0.109 |

0.201 |

2.529 |

0.013 |

|

Destination attractiveness |

0.145 |

0.093 |

0.130 |

1.556 |

0.122 |

|

Explanatory Variables |

|||||

|

First generation FB |

-0.328 |

0.385 |

-0.160 |

-.852 |

0.396 |

|

Second generation FB |

-0.821 |

0.356 |

-0.329 |

-2.305 |

0.023 |

|

Non-managerial family involvement |

0.012 |

0.089 |

0.013 |

0.134 |

0.893 |

|

Managerial family involvement |

-0.942 |

0.503 |

-0.243 |

-1.871 |

0.064 |

|

No board of directors (BD) |

-0.054 |

0.411 |

-0.029 |

-0.132 |

0.895 |

|

Some members of the BD are family members |

-0.202 |

0.911 |

-0.030 |

-0.222 |

0.825 |

|

All members of the BD are family members |

0.092 |

0.484 |

0.025 |

0.191 |

0.849 |

|

Use of specific FB governance mechanisms |

0.545 |

0.239 |

0.284 |

2.279 |

0.024 |

|

Head’s qualifications |

1.530 |

1.142 |

0.411 |

1.339 |

0.183 |

|

Moderating Variables |

|||||

|

First generation FB x Head’s qualifications |

13.630 |

4.778 |

2.366 |

2.853 |

0.005 |

|

Second generation FB x Head’s qualifications |

2.687 |

1.586 |

0.405 |

1.694 |

0.093 |

|

Non-managerial family involvement x Head’s qualifications |

1.002 |

0.506 |

0.732 |

1.981 |

0.050 |

|

Managerial family involvement x Head’s qualifications |

8.260 |

2.099 |

1.658 |

3.936 |

0.000 |

|

No board of directors (BD) x Head’s qualifications |

-12.893 |

5.255 |

-1.945 |

-2.453 |

0.016 |

|

Some members of the BD are family members x Head’s qualifications |

5.163 |

2.397 |

0.638 |

2.154 |

0.033 |

|

All members of the BD are family members x Head’s qualifications |

-2.498 |

1.799 |

-0.377 |

-1.389 |

0.167 |

|

Use of specific FB mechanisms x Head’s qualifications |

1.033 |

0.976 |

0.200 |

1.058 |

0.292 |

|

R |

0.609 |

R² |

0.371 |

||

|

R² adjusted |

0.265 |

Statistical value F |

3.507 |

||

|

Significance F |

0.000 |

||||

The results for the control variables indicate that only two of them are significant: training effort and the attractiveness of the environment.

4.2. Results of direct effects

As can be seen in Table 3, hypothesis H1, which posits a positive effect of the first generation of family businesses, is not supported (β = - 0.160; p > 0.10). Conversely, there is strong support for H2 (β = - 0.329; p < 0.05). Therefore, the results indicate that in second-generation family businesses the conditions are not advantageous for the development of managerial capabilities.

Regarding the hypotheses concerning family involvement in managerial and non-managerial roles, although the effect is not particularly strong for H4, it is significant, as can be seen in Table 3 (β = - 0.243; p < 0.10); therefore, H4 is accepted. However, H3 is not corroborated (β = 0.013; p > 0.1). In this regard, it can be inferred that the problems that may be caused by family involvement in the company stem from senior positions.

As for the aspects related to the board of directors, surprisingly none of the proposed relationships turn out to be significant; therefore, we reject H5 (β = - 0.029; p > 0.1), H6 (β = - 0.030; p > 0.10), and H7 (β = - 0.025; p > 0.10).

With regard to the use of governance mechanisms unique to the family business, there is strong evidence that the establishment of such instruments favors the development of managerial capabilities, as can be seen in Table 3 (β = 0.284; p < 0.05); therefore, hypothesis H8 is accepted.

Finally, in this first block, one of the proposed hypotheses refers to the qualifications of the head of the family business, a variable that is then used as a moderator. Thus, H9 proposes a direct effect of this aspect on the development of managerial capabilities. However, we must reject this hypothesis, because although the effect is positive (Table 3), it is not significant (β = 0.411; p > 0.10).

4.3. Results of moderating effects

This second block of results focuses on the hypotheses relating to the moderating effect of the qualifications of the head of the family business, the results of which can be seen in the bottom part of Table 3. Regarding the dominant generation in companies, as expected, a properly qualified head of the family business transforms the effects previously observed; thus, when the head of a first-generation company is a professional, it does contribute to the development of managerial capabilities (β = 2.366; p < 0.05). A change is also observed in second-generation companies: although the effect is not so strong, the professionalization of the head of the company also helps these companies tackle the obstacles they faced and establish a more conducive environment for the development of managerial capabilities (β = 0.405; p < 0.10). Therefore, hypotheses H10 and H11 are accepted.

Regarding the moderating effect on family involvement, when the head of the company is appropriately qualified, the presence of family members in the company no longer represents an obstacle; in fact, it contributes to the promotion of managerial capabilities (β = 0.732, p < 0.10), particularly in the case of managerial family involvement (β = 1.658, p < 0.05). Therefore, hypotheses H12 and H13 can be accepted.

Considering the hypotheses raised with respect to the board of directors, in this case H14 and H15 are supported (β = - 1.945; p < 0.05 and β = 0.638; p < 0.05, respectively). With regards to hypothesis H16, although the effect is negative, it is not significant, so we cannot accept this hypothesis (β = - 0.377, p > 0.10). Thus, the presence of a board of directors seems key in companies where the head is professionally qualified and that are therefore more professionalized and formalized; that is, companies where the lack of board hinders the development of efficient managerial capabilities. Likewise, when some members of the board are family members, family and business interests can be more formally aligned, thus contributing to the development of management capabilities. Lastly, a board composed entirely of family members does not have any significant effect on managerial capabilities, although it does have a small negative influence.

Finally, as to the use of governance mechanisms specific to the family business, a positive but non-significant effect is observed when this variable is moderated by the head’s qualifications (β = 0.200, p > 0.10). Therefore, hypothesis H17 must be rejected.

The following table includes a summary of the results obtained, showing whether each hypothesis should be accepted or rejected.

Table 4. Summary of results

|

Hypotheses |

Results |

|

H1. The first generation of the family business positively affects the development of managerial capabilities. |

7 |

|

H2. The second generation of the family business negatively affects the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H3. The greater the non-managerial family involvement in the family business, the less the development of effective managerial capabilities. |

7 |

|

H4. The greater the family managerial involvement in the family business, the less the development of effective managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H5. The lack of a board of directors hinders the development of managerial capabilities in the family business. |

7 |

|

H6. A certain degree of family involvement in the board of directors favors the development of management capabilities in the family business. |

7 |

|

H7. A board of directors made up exclusively of family members hinders the development of management capabilities in the family business. |

7 |

|

H8. The use of specific family business governance bodies and mechanisms favors the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H9. The professional qualifications of the head of the family business have a positive effect on managerial capabilities*. |

7 |

|

H10. If the head of a first-generation family business has a professional qualification, this has a positive influence on the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H11. If the head of a second-generation family business has a professional qualification, this has a positive influence on the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H12. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a higher degree of non-managerial family involvement contributes positively to the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H13. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a higher degree of family involvement in management contributes positively to the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H14. Even when the head of the family business has a professional qualification, the lack of a board of directors is an obstacle to the development of managerial capabilities in the family business. |

3 |

|

H15. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a certain degree of family involvement in the board of directors continues to be beneficial for the development of managerial capabilities. |

3 |

|

H16. If the head of the family business has a professional qualification, a board of directors made up entirely of family members has a negative influence on the development of managerial capabilities. |

7 |

|

H17. The use of governance bodies and mechanisms in family businesses where the top manager has a professional qualification favors the development of managerial capabilities. |

7 |

5. Conclusions

Based on a detailed analysis of the specific structure of family businesses, we formulated several hypotheses regarding the possible effects of the characteristics of the tourist family business on their managerial capabilities. Moreover, the professionalization of the family business is proposed as a potential solution to the negative effects that the characteristics of the family business could have on the development of managerial capabilities.

In many cases, the results support our hypotheses, although in others they contradict the proposed hypotheses. The general conclusion is that the professionalization of the head of the family business transforms it in various ways, creating an environment conducive to the development of managerial capabilities. More specific conclusions are presented below.

First, the results in terms of direct effects show that first-generation family businesses do not contribute to the promotion of managerial capabilities, although they do not pose an obstacle either. These results support the findings of other authors, who argue that although in the initial stages the founders do possess leadership and entrepreneurial skills that contribute to the development of managerial capabilities, many of them later become settled, and averse to risk and changes (Dertouzos et al., 1989; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2006; Salvato, 2004; Zahra et al., 2004). These attitudes can be transferred to the second generation, who adopt the same attitude observed in the late stages of the first generation, exacerbating the situation. These problems are solved when the moderating effects are introduced, which may indicate that a professionally-qualified head can create a more entrepreneurial outlook throughout the company, particularly in the founding generation. This effect occurs to a lesser degree in second-generation companies, probably due to the fact that certain values become rooted in the company, making them more difficult to address. That said, the head of the company can still modify them such that they do not pose an obstacle and may even benefit the company.

Second, the conclusions relating to family involvement in the company may suggest that problems arise in senior positions that entail greater responsibility, rather than in non-managerial positions. Family members are more likely than non-family members to seek managerial positions despite not having the appropriate training and knowledge. On the one hand, this can generate conflict among family members and among other more qualified potential managers and, on the other hand, it can be a drawback when it comes to solving problems for which they are not properly qualified, obstructing attitudes that can promote entrepreneurial values in the business.

Although a well-qualified head has implications for both types of employees, it is particularly beneficial when it comes to family managerial involvement. This indicates that the head can transfer his/her professionalism to the family managers of the business, transmitting through them cultural values of change, entrepreneurial orientation and a strategic vision.

Likewise, the fact that these managers are both well qualified and family members is highly beneficial when they set aside their personal interests for the good of the business. In this regard, they may consider themselves as “guardians” of the business (Corbetta & Salvato, 2004; Eddleston & Kellermans, 2007; Eddleston et al., 2008), becoming more deeply involved and aligning their interests with those of the company.

Regarding non-managerial family employees, these assumptions also apply to this group, although probably to a lesser degree as these employees do not have so much responsibility and do not perceive that their decisions or attitudes have such a decisive influence on the company. The general conclusion for both groups refers to the relevant role played by the professionalization of the head when it comes to securing benefits from family involvement in the company.

Third, the use of governance bodies such as the board of directors and other mechanisms specific to family businesses act as substitutes. When the effects are not moderated, the presence of a board of directors and family involvement in this body do not influence managerial capabilities. Conversely, the use of other mechanisms does appear to be relevant for the development of this type of capability. However, when these relationships are moderated, the effects are reversed: the variables relating to the board of directors have a significant influence while the other family business mechanisms have a non-significant effect. In this case, it can be concluded that these instruments are, to a certain extent, substitutes, so that in more formalized and professionalized companies, the existence and, therefore, the composition of the board of directors will be more relevant, to the detriment of the use of other mechanisms that are less professional and more typical of family businesses. Overall, most of the family tourism companies in the sample do not have a board of directors; as such, this variable only turns out to be significant when it is moderated, which may indicate that companies with a highly qualified head tend to use this type of body more. In addition, a board of directors plays a key role in the development of managerial capabilities. That said, the board of directors should include both family and non-family members in order to ensure everyone’s interests are served and that the decisions made take into account the needs of all members, favoring entrepreneurial and strategic attitudes that involve all parties.

The fact that the use of governance mechanisms specific to the family business is not really moderated by a qualified head may also indicate that these instruments are used as an alternative to professionalization. Thus, in companies that are already professionalized these mechanisms tend to be less effective. However, given the positive effects of these bodies and mechanisms on managerial capabilities in family businesses as a whole, they should be assigned greater importance within this group of businesses. Nevertheless, given that the use of these mechanisms tends to increase in companies with greater generational complexity (Bañegil et al., 2011), it should be borne in mind that few companies survive beyond the third generation.

Finally, it is worth noting the evidence obtained with respect to the qualifications of the head of the business. It can be concluded that these qualifications only have an impact on managerial capabilities if this professionalization can be applied to efficiently transform the structure and behavior of the family business. Therefore, the mere fact of being highly qualified does not have an impact if it is not used for the benefit of the business.

A number of implications can be drawn from these conclusions. In terms of research, there is a need for a more in-depth study of what other aspects of the family business contribute to or hinder the development of managerial capabilities. The fact that the constant was very significant points to the existence of other aspects that can affect the managerial capabilities in the family business. There has been very little research into these capabilities in family businesses, as most of the studies in this field focus on elements that influence performance. Likewise, more attention should be paid to the heads of the family business and the variables that may represent a solution to the problems that family businesses face.

Furthermore, this study has some implications for family businesses. Training and professionalization are critical for these types of companies when it comes to developing and acquiring distinctive capabilities that can help them improve their position in the market. It is also worth noting that each job position should be filled by the best possible candidate, regardless of whether or not this is a family member (Hall & Nordqvist; 2008). However, all else being equal, companies that achieve a high degree of professionalization benefit from hiring family members, especially in managerial positions, since they feel more identified with the business than non-family members do. The results also underline the importance of using the family business mechanisms to share values and create certain rules to follow in order to prevent conflict while promoting a common culture for all members of the company.

Finally, it should be noted that this study is not free from limitations. In the first place, the R2 is not particularly high, and the constant was very significant; however, it should be borne in mind that only aspects related to the governance structure of the family business and family involvement in the business have been included in the model, and there may be other variables that can explain the variance in the development of managerial capabilities in the specific case of the family business. Furthermore, some of the conclusions are influenced by the cross-sectional nature of the research design, which has implications for the prediction of causality. Lastly, the focus on the Spanish tourism sector may also limit the applicability of these conclusions to other sectors or territories. These limitations described here, as well as the implications in terms of research, point to future avenues for research.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a project funded by the Universitat Jaume I with reference UJI-A2019-20. It is also developed within the framework of the research program of the Vicerectorat d’Investigació de la UV, convocatòria d’Accions Especials, file UV-INV-AE-1554975. Likewise, the project is funded by the Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica y Técnica y de Innovación 2021-2024 of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, with the reference PID2020-119642GB-I00. Moreover, the author José María Fernández Yáñez has the support of the predoctoral grant PD-UJI/2019/13.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. USA, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 573-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

Arteaga, R., & Menéndez-Requejo, S. (2017). Family constitution and business performance: moderating factors. Family Business Review, 30(4), 320-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486517732438

Astrachan, J. H. (2010). Strategy in family business: toward a multidimensional research agenda. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(1), 6-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2010.02.001

Astrachan, J. H., Allen, I. E., & Spinelli, S. (2002). Mass mutual/Raymond Institute American family business survey. Springfield, MA: Mass Mutual Financial Group.

Ateljevic, I., & Doorne, S. (2000). Staying within the fence: lifestyle entrepreneurship in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(5), 378-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580008667374

Bantel, K. A., & Jackson, S. E. (1989). Top management and innovations in banking: Does the composition of the top team make the difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10(S1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100709

Bañegil, T. M., Barroso, A., & Tato, J. L. (2011). Profesionalizarse, emprender y aliarse para que la empresa familiar continúe. Revista de Empresa Familiar, 1(2), 27-41.

Barach, J. A., Ganitsky, J. B., Carson, J. A., & Doochin, B. A. (1988). Entry of the next generation: strategic challenge for family business. Journal of Small Business Management, 26(2), 49-56.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0022-3514.51.6.1173

Barontini, R., & Caprio, L. (2006). The effect of family control on firm value and performance: evidence from continental Europe. European Financial Management, 12(5), 689-723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-036X.2006.00273.x

Basco, R. J. T. (2006). La investigación en la empresa familiar: un debate sobre la existencia de un campo independiente. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 12(1), 33-54.

Benavides, C. A., Guzmán, V. F., & Quintana, C. (2011). Evolución de la literatura sobre empresa familiar como disciplina científica. Cuadernos de Economía de la Empresa, 14(2), 78-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cede.2011.02.004

Birley, S., Ng, D., & Godfrey, A. (1999). The family and the business. Long Range Planning, 32(6), 598-608. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(99)00076-X

Blumentritt, T. P., Keyt, A. D., & Astrachan, J. H. (2007). Creating an environment for successful nonfamily CEOs: an exploratory study of good principals. Family Business Review, 20(4), 321-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00102.x

Boling, J. R., Pieper, T. M., & Covin, J. G. (2016). CEO tenure and entrepreneurial orientation within family and nonfamily firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(4), 891-913. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12150

Braun, M., & Sharma, A. (2007). Should the CEO also be chair of the board? An empirical examination of family-controlled public firms. Family Business Review, 20(2), 111-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00090.x

Broekaert, W., Andries, P., & Debackere, K. (2016). Innovation processes in family firms: the relevance of organizational flexibility. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 771-785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9760-7

Brunninge, O., & Nordqvist, M. (2004). Ownership structure, board composition and entrepreneurship: evidence from family firms and venture capital backed firms. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 10(1/2), 85-105. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550410521399

Burkart, M., Panunzi, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58(5), 2167–2201. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00601

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource -and knowledge- based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Carmeli, A., & Tishler, A. (2006). The relative importance of the top management team´s managerial skills. International Journal of Manpower, 27(1), 9-36. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720610652817

Carnes, C. M., & Ireland, R. D. (2013). Familiness and innovation: Resource bundling as the missing link. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1399-1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12073

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249-265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x

Chang, S. J., & Shim, J. (2015). When does transitioning from family to professional management improve firm performance? Strategic Management Journal, 36(9), 1297-1316. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2289

Chrisman, J. J., & Patel, P. C. (2012). Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 976-997 https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0211

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Sharma P. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 555-576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00098.x

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Sharma, P. (2003). Current trends and future directions in family business management studies: Toward a theory of the family firm. Coleman White Paper Series, 4(1), 1-63.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2018). Governance mechanisms and family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(2), 171-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717748650

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Churchill Jr, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

Cirillo, A., Pennacchio, L., Carillo, M. R., & Romano, M. (2019). The antecedents of entrepreneurial risk-taking in private family firms: CEO seasons and contingency factors. Small Business Economics, 56, 1571–1590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00279-x

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Science, 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441

Corbetta, G., & Salvato, C. (2004). Self-serving or self-actualizing? Models of man and agency costs in different types of family firms: a commentary on ‘comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 355-362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00050.x

Cromie, S., Stevenson, B., & Montieth, D. (1995). The management of family firms: an empirical investigation. International Small Business Journal, 13(4), 11-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242695134001

Cucculelli, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Product innovation, firm renewal and family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 90-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.02.001

Daily, C. M., & Dollinger, M. J. (1992). An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally managed firms. Family Business Review, 5(2), 117-136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1992.00117.x

Daspit, J. J., Long, R. G., & Pearson, A. W. (2019). How familiness affects innovation outcomes via absorptive capacity: a dynamic capability perspective of the family firm. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(2), 133-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.11.003

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Pizzurno, E., & Cassia, L. (2015). Product innovation in family versus nonfamily firms: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12068

Dekker, J., Lybaert, N., Steijvers, T., & Depaire, B. (2015). The effect of family business professionalization as a multidimensional construct on firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 516-538. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12082

Dertouzos, M. L., Lester, R. K., & Solow, R. M. (1989). Made in America: regaining the productive edge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Diéguez-Soto, J., Manzaneque, M., & Rojo-Ramírez, A. A. (2016). Technological innovation inputs, outputs, and performance: the moderating role of family involvement in management. Family Business Review, 29(3), 327-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516646917

Dillman, D. A. (1978). Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Duran, P., Kammerlander, N., Van Essen, M., & Zellweger, T. (2016). Doing more with less: innovation input and output in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1224-1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0424