European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 100-110

Reacting to a Generalised Crisis. A Theoretical Approach to the Consumption of Slack Resources in Family Firms

María A. Agustía, Encarnación Ramosa, Francisco J. Acedoa*

a Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M10, M21, M49

KEYWORDS

Consumption, Crisis, Family firms, Organizational slack, Performance

CÓDIGOS JEL

M10, M21, M49

PALABRAS CLAVE

Consumo, Crisis, Empresas familiares, Rendimiento, Slack organizativo

Abstract Research to date has shown that companies can accumulate resources over those strictly needed in order to overcome the uncertainty associated to a crisis. But the usage, redeployment, or consumption of this excess of resources when facing an adverse environment is yet underexplored. As suggested by the literature, the condition of family business can exert an important effect in such behaviour. This paper proposes a th eoretical framework, focused on family business, about how firms manage the different slack resources when facing a general crisis. We make a call on family business scholars to leverage our propositions and the existing literature on slack resources to develop a guidance for family owners when facing an economic downturn.

La reacción frente a una crisis generalizada: Un enfoque teórico al consumo de recursos en las empresas familiares

Resumen Las investigaciones realizadas hasta la fecha han demostrado que las empresas pueden acumular recursos por encima de los estrictamente necesarios para superar la incertidumbre asociada a una crisis. Pero la utilización, redistribución o consumo de este exceso de recursos cuando se enfrentan a un entorno adverso está todavía poco explorada. Como sugiere la literatura, la condición de empresa familiar puede ejercer un efecto importante en dicho comportamiento. Este trabajo propone un marco teórico, centrado en la empresa familiar, sobre cómo las empresas gestionan los diferentes recursos slack cuando se enfrentan a una crisis. En este sentido, se plantea la necesidad de que los investigadores en el campo de la empresa familiar aprovechen nuestras propuestas, y la literatura existente sobre los recursos slack, para desarrollar una guía que facilite la toma de decisiones en las empresas familiares cuando se enfrentan a una recesión económica.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10626

Copyright 2021: María A. Agustí, Encarnación Ramos, Francisco J. Acedo

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: fjacedo@us.es

1. Introduction

Understanding how firms are able to cope with uncertainty and overcome threatens have long attracted the interest of the academic community (Gral, 2014; Karacay, 2017). To face this situation, exceeding resources, or slack resources has been considered a positive element to assure the survival of the firm (Bourgeois, 1981).

Literature to date has reflected the possibility of addressing a greater number of goals, but also offers some protection against unfavourable events such as internal crises (Bourgeois, 1981) or environmental economic crises (Zona, 2012).

This paper develops a conceptual model of how family firms consume and redeploy the slack resources when facing an environmental jolt, such an economic crisis or an unanticipated event as it is the actual sanitary crisis. Thus, we advance prior works on slack resources and family firms (Campopiano et al., 2019), in particular we consider the possibilities to downsize or retrench (Agarwal et al., 2009), as firms consume accumulated resources when difficulties arise (Bourgeois, 1981). The proposed theoretical model, thus, contributes to further our understanding of resilient family firms when confronting an economic downturn, and the process that may be undertaken in order to survive, and, if possible, keep adequate performance outcomes. Besides, it contributes to the slack resources literature by considering the usage or redeployment of these excesses of resources as a determinant of performance instead of the traditional stock consideration.

The paper structures as follows. First, we develop a theoretical framework that will be used as a basis for the models. As the different possible effects of the slack resources are unveiled, we build different propositions. The different propositions together conform the proposed model. The paper concludes with a discussion, possible implications, and future research lines.

2. Theoretical Framework

Slack resources have been defined from a diverse set of theories and perspectives (Karacay, 2017). Within the theory of organizational behaviour, they are conceptualized as those excess of resources that allow companies to adapt to unexpected fluctuations (Cyert & March, 1956, p. 52). Bourgeois (1981) complemented this perspective with the opportunity of strategic use of these resources beyond passive purposes (Voss et al., 2008), thereby introducing versatility in its use (Sharfman et al., 1988).

Slack is generally viewed as a positive factor (Gral, 2014; Karacay, 2017), since slack can be used as a motivating force for decision-making and a resource for conflict resolution, providing the possibility to solve more goals. In addition, slack resources can provide some protection against adverse events such as internal crises (Bourgeois, 1981) or economic recessions. Thompson (1967) raised the need to establish mechanisms that would allow the organisation to keep the core of operations isolated from possible negative environmental influences. In this sense, the literature has valued organizational slack as a key factor that facilitates buffering the variations and discontinuities caused by environmental uncertainty (Bentley & Kehoe, 2020; Bradley et al., 2019). Therefore, having an excess of resources over those strictly needed will allow firms to cope with unforeseen changes in the environment (Godoy Bejarano et al., 2020; Stan et al., 2014). In this sense, organizational slack can be defined as a cushion that provides an essential buffer within organizations against financial crises (Cheng & Kesner, 1997, p. 3).

Literature has mainly suggested that having slack resources mitigates the negative influences of the environment (Godoy-Bejarano et al., 2020) by avoiding excessive dependence on external resources (Fiegenbaum & Karnani, 1991; Meier et al., 2013; Nadkarni & Narayanan, 2007; Shimizu & Hitt, 2004; Thomas, 2013). Thus, slack resources contribute to performance stability by increasing resource flexibility and ultimately contributing to firm survival in environmental uncertainty (Aaker & Mascarenhas, 1984; Arslan-Ayaydin et al., 2014; Evans, 1991; Kulkarni & Ramamoorthy, 2005).

In addition to playing a role of assistance to avoid the problems arising from the scarcity of resources from the environment, slack resources also entail a high level of flexibility for management. This flexibility facilitates proactive behaviours, allowing companies to create strategic options that allow them to achieve competitive advantages (Klingebiel & Adner, 2015; Sanchez, 1993; Wu & Tu, 2007). Therefore, the presence of slack has been associated with the flexibility and manoeuvrability of resources as it favours the adaptation to new competitive situations due to sudden environmental changes (Donada & Dostaler, 2005).

Slack resources are, therefore, a cushion for improvement and facilitating a short-term adaptation process (Godoy-Bejarano et al., 2020). In this sense, Sharfman et al. (1988, p. 603) deepen into this process remarking that the buffering mechanism involved in slack resources differs from other buffers. The reason for this assertion is that slack resources present more functions than just acting as a cushion (Bourgeois, 1981).

Notwithstanding, slack resources have not always been considered as positive. This type of resources has additionally been related with agency problems (Brush et al., 2000), as it expands the power to decide of managers and may suggest less than optional use by management, leading to inefficiency and negative results (George, 2005; Jensen, 1986; Love & Nohria, 2005).

All in all, research to date on the effect of slack resources against a crisis (Bradley et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2015; Zona, 2012) indicates that this type of resources allows companies to react to uncertain situations (Meier et al., 2013) and protect themselves to ensure their survival (Evans, 1991). Tan and Peng (2003) argue that, in the face of a crisis, the scarcity of resources that firms can obtain from the environment forces companies to adjust their efficiency levels through the use of accumulated resources to ensure survival. However, it has also been observed by researchers that maintaining high levels of slack resources during munificent periods can negatively affect performance (Vanacker et al., 2017). In this sense, the availability of high levels of slack resources, especially those considered flexible (Arslan-Ayaydin et al., 2014), makes it possible to create multiple strategic options for dealing with a crisis (Klingebiel & Adner, 2015), allowing, through redeployment or consumption, to protect from external adversities (Wenzel et al., 2020).

2.1. Slack resources and the family firm

The study of slack resources in the family businesses field has yet to be developed (Laffranchini & Braun, 2014), and the effect of how companies react against crises, by means of the use and redistribution of these resources, remains unexplored (Campopiano et al., 2019).

Most research to date that has studied the functions of slack resources in relationship to family businesses has done it mainly in relation to how this excess of resources condition their international behaviour (Alessandri et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2011; Xu & Hitt, 2020) or innovation (Campopiano et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2017).

It is worth noting that slack resources in family firms have multiple particularities that may lead to different performance. In this sense, the agency problems derived from the possession or use of slack resources (George, 2005) must be considered as different to those appeared in non-family firms due the nature of the firm’s capital, and to the specific behaviours and outcomes associated with family firms (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Kotlar & De Massis 2013). Laffranchini and Braun (2014) show that the access of family managers to the available slack seems to have a concave relationship with the firm’s performance, however this outcome is moderated by the corporate governance structure of the family firm, and depending on the type of family firm, it is possible to see the predominance of an agency-based approach (De Massis et al., 2018) or a behaviour associated with a stewardship-based view. Mahto and Khanin (2015) show that the high-discretion slack affects the family business strategy as they favour a risk-seeking strategy over the traditional risk-averse strategy. However, as it happens in general in the literature related to slack resources, the study of their consumption and the way in which companies redistribute these resources is still scarce (Agusti et al., in press).

3. A Model on the Consumption of Slack Resources

Bourgeois (1981) suggested, in his key article on the measurement of slack resources, that for the analysis of this type of resources it would be necessary to study whether companies were “slack winners or slack losers” (p. 38). This leads us to argue that slack resources, against what has been mostly proposed in the literature (Daniel et al., 2004; Gral, 2014; Karacay, 2017), should be considered as a flow and not a resource stock (Dierickx & Cool, 1989). Lavie (2012) posited that there was a great lack of knowledge about the process through which companies accumulate and use resources, which is a confirmation of what was previously stated from the resource-based view. This gap is also applicable to slack resources (Argilés-Bosch et al., 2018; Love & Nohria, 2005; Su et al., 2009; Tsang, 2006).

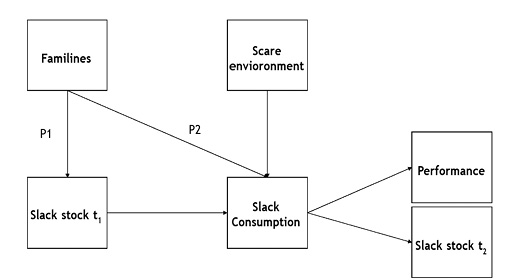

Namiki (2013, 1015) captured the effect that the reduction of slack resources has on performance in a situation of financial crisis through the variation of resources. In our case we depart from the process of resource accumulation and deployment model by Lavie (2012), and the proposal by Campopiano et al. (2019) on the effect of environmental jolts and the deployment of slack resources, we propose the model depicted in Figure 1.

In this model (Figure 1), two fundamental facts stand out. On the one hand, family businesses, due to their differentiating characteristics, will show a different level of slack than non-family businesses. This is in line with prior research that resource accumulation and divestment are strongly influenced by family objectives (Campopiano et al., 2019; Kellermanns, 2005; Sharma & Manikutty, 2005) as these objectives condition the development of the organization.

Figure 1. How family firms may affect to slack consumption

We could take this assertion further as the different types of family business according to their familiness will show a different tendency to accumulate different stocks of slack in periods of prosperity. Van Essen et al. (2015, p. 170) observed that family firms “may choose to operate with more organizational slack” assuming a potentially inefficient behaviour, but on the premise that slack increases the survivability of the firm against unanticipated shocks. In the same way, and following Campopiano’s (2019) proposal, when faced with a change in the environmental conditions, the family nature of the company will lead to a modification of the stock of resources different from that undertaken by non-family businesses (Lorenzo-Gómez, 2020). Accordingly, we consider that some of the main forms of consumption or redeployment of slack resources that have been proposed in the literature (Agusti et al., in press) will also be affected. Therefore, we propose that:

P1: Family firms will tend to accumulate more slack resources than non-family firms.

The existing evidence in literature has given a dynamic character to slack resources. In this sense, several authors have contemplated the effects of slack resources during periods of financial crisis (Bradley et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2015; Zona, 2012), since it allows them to act in front of uncertain situations (Meier et al., 2013) or to protect themselves to guarantee their survival (Evans, 1991). As aforementioned, slack resources have a twofold effect. Thus, during a crisis, resource scarcity forces firms to use their slack resources to ensure survival (Tan & Peng, 2013), although maintaining high levels of slack resources in periods of bounty can adversely affect performance (Vanacker et al., 2017). As a result of these premises, we propose that:

P2: Family firms will present a different pattern of slack resource consumption, to non-family firms, when facing an external crisis.

However, in order to understand the possible effect, as well as the different possibilities in the management of this type of resources by the company, it is necessary to take into account the multidimensional nature of these resources (Geiger & Cashen, 2002), and the diversity of measures (Bourgeois, 1981) or configurations of these (Marlin & Geiger, 2015). In a more detailed way, we can say that the available resources present a great versatility (Arslan-Ayaydin et al., 2014), which makes it easier for the company to create different strategic options (Klingebiel & Adner, 2015), allowing through redeployment or consumption to stop the effects of external or internal adversities. Similarly, high levels of potential slack will facilitate survival in periods of shortage by avoiding the need to seek external financing for the company itself (Bourgeois, 1981).

However, literature on slack consumption is still scarce (Agusti et al., in press), and evidence of this consumption has to be sought in turnaround literature. In this sense, previous studies investigating the impact of slack reduction have done so on innovation capacity (e.g., Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2010), and have focused on human resources (e.g., Cheng & Kesner, 1997; Kim & Ployhart, 2014; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2010; Wagan, 1998), assessing the effect of size reduction on performance. Namiki (2016) considers that the reduction of slack, in terms of cash and overheads, is similar to the cost and asset cuts associated with companies in crisis seeking recovery. In this sense, Lim et al. (2013, p. 43) define slack as the process of deliberately eliminating assets and/or reducing costs as a means to increase the efficiency of the company. This definition is in line with the agency theory associated with slack ownership (George, 2005).

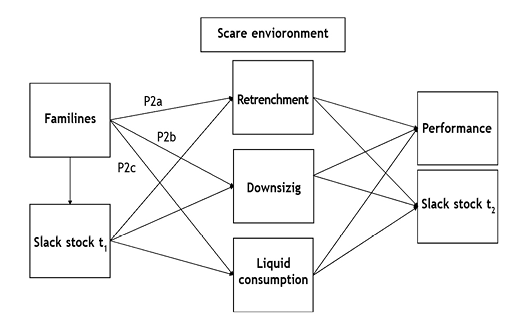

In this sense we apply the literature that is, directly or indirectly, related to slack resources, in which this issue has been analysed in specific contexts, such as in cases of turnaround and more specifically in retrenchment, downsizing processes in relation to human resources, or in liquidity management when the company faces widespread financial crises. It is necessary to note that downsizing has been considered as a type of retrenchment strategy. In our study, we differentiate these two terms by associating downsizing to human resources costs and retrenchment to other types of expenses (general and management costs, R&D, marketing, etc.). The rationale followed by the following model responds to this consideration. In this sense, and from a crisis perspective in which resources are scarce, we could propose the model presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Family firm and the different forms of slack reduction

4. An Approach to the Different Forms of Consumption of Slack Resources in the Family Business

The key question in this process is to understand whether these processes are the same in the family business. It is generally accepted that family firms have a different risk orientation than non-family firms (Naldi et al., 2007; Schulze et al., 2002; Zahra, 2005). Zahra (2007), among others, maintains that family enterprises have a unique set of characteristics and capabilities that differentiate them from the rest in their management and decision-making. Even among the companies considered as family businesses it is possible to identify characteristics which establish a taxonomy within the very concept of family business (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011). Similarly, it has been considered the effect that family businesses present a great diversity of objectives, financial and non-financial (Cennamo et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2012), resulting in a diversity of responses to environmental jolts (Campopiano et al., 2019).

Retrenchment can be defined as “the deliberate elimination of assets and/or reduction of costs as a means to increase the efficiency of the company” (Lim & Mccann, 2013, p. 43). This definition links directly to slack resource management from an inefficiency-based perspective (George, 2005). Indeed, cost reductions refer to the net reduction of total costs such as selling, general and administrative expenses (SGA); financial expenses; and other costs (marketing or R&D associated costs) (Lim & Mccann, 2013; Robbins & Pearce, 1992), which allows linking this management process to the use or application of recoverable slack. Most of the literature raises the use of these cuts in situations of business crisis, but more recently researchers have also looked at the contingency factors influencing the effects of these cuts (Dewitt, 1998; Francis & Pett, 2004; Guthrie & Datta, 2008; Morrow et al., 2004). These cuts, particularly in costs, may also be a response to declines in the munificence of the environment (Boyne & Meier, 2009).

In this regard, family firms are more flexible than non-family firms because of the organizational and management models they employ (Nodqvist et al., 2008), taking into account the differences in the financial information management (Basly & Saadi, 2020). Casillas et al. (2010, 2013) showed that these management systems allowed them to speed up decision-making processes and therefore to be more responsive. In particular, the family nature can favour the rapid development of readjustment or change of direction strategies, as these companies have demonstrated a greater entrepreneurial orientation (Casillas et al., 2010; Nordqvist & Melin, 2010). This entrepreneurial orientation not only allows this type of company to identify and exploit new business opportunities, but also provides them with a greater capacity to react to unsatisfactory results. In this sense we propose that:

P2a: In a situation of economic crisis, family businesses will make faster use of retrenchment mechanisms than non-family businesses.

As aforementioned, and considering human resources separately to the other costs considered in the retrenchment strategy, we find that within the extensive literature on downsizing, some studies have analysed how this process affects the outcome of innovation (Dougherty & Bowman, 1995; Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2010) and company performance (Guthrie & Datta, 2008; Love & Nohria, 2005). Downsizing is defined as “the decision by a firm to reduce its capacity of those human resources which exceed the requirements necessary for the efficient operation of the firm” (Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2010, p. 485), this definition being directly related to the recoverable slack. Mellahi and Wilkinson (2010) point out that one of the main weaknesses of studies between slack and innovation is their exclusive focus on the level of slack available in organisations to the extent that they neglect the potential impact of sudden slack reduction on innovation, as family firms consider innovation in a different way (Ferrari, 2019). This is therefore a major gap in research, as companies regularly adjust their slack level to suit the business environment in which they operate in order to remain competitive (Cheng & Kesner, 1997).

However, the empirical evidence seems to suggest that family-owned or controlled enterprises have a different approach to reducing the number of employees from non-family ones (Stavrou et al., 2006). Thus, we find work that has shown that family management moderates the relationship between firm profitability and the likelihood of downsizing (Block, 2010). The main justification for this is that family firms are less likely to downsize than non-family firms because their objectives are not solely related to financial performance. In this sense, there is work that has identified how the fluctuation of the number of employees in family firms is lower in periods of crisis (Block, 2010; Lee, 2006; Machek, 2017), with family firms generally being larger job creators than non-family firms (Amato et al., 2020). These findings can be supported by the socioemotional wealth theory. Under the immediate threat of a loss of socioemotional wealth, family managers will become loss averse; hence, they will be willing to prefer to preserve their socioemotional wealth over other goals (Chrisman & Patel 2012). Consequently, we set the following proposition:

P2b: In a situation of economic crisis, family businesses will use less downsizing mechanisms than non-family businesses.

Finally, in the area of finance there are numerous studies that analyse liquidity management and other financial decisions of companies in a situation of generalised crisis (Campello et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2020; Nason & Patel, 2016). These financial resource slacks are usually related to the available and potential slack (Voss et al., 2008), and are linked to the pecking order theory (Myers & Majluf, 1984). The available slack, associated with liquid assets, is an important element of protection against the environment, facilitating adaptation and the search for options (Deb et al., 2017; Kim & Bettis, 2014). Thus, in circumstances where a rapid response is required, this type of resource is particularly important (Kim & Bettis, 2014), being vital for survival and crisis response (Arslan-Ayaydin et al., 2014). Along with liquidity, some authors have argued that firm leverage, potential slack, is of particular importance in crisis situations, even beyond liquid resources (Arslan-Ayaydin et al. 2014). Notably, empirical evidence has shown that firms with higher levels of slack show a greater decline in profitability at the beginning of the crisis; however, they show a higher increase in profitability in the recovery (Latham & Braun, 2008, 2009).

In terms of how family businesses manage liquidity, Lozano (2015) outlines the relevance of strategic decisions guided by conservatism, flexibility, long-term vision and the active control that family businesses have over cash accumulation. His results show that family firms tend to accumulate cash for both strategic reasons and fortheir own particularities, achieving optimal cash accumulation more efficiently than non-family firms.

Several other factors also affect cash accumulation, such as liquid replacement assets, cash flow volatility, leverage, investment opportunities and size. Accumulated cash therefore depends first and foremost (using generated cash flow and size as the usual control variables) on the firm’s decision to hold liquid assets - rather than, or in addition to, cash - or to have credit facilities (Hardin et al., 2009).

Cash is the most conservative means of payment and is therefore particularly relevant to the company’s strategic decisions. Family businesses have a broader investment horizon (Miller et al., 2011; Pindado et al., 2011), so the family is likely to act in the best interests of the business most of the time. Companies controlled by the family have broader investment horizons (Miller et al., 2011; Pindado et al., 2011), so the family is likely to act in the best interests of the company most of the time.

The flexibility of family businesses in the decision-making process is an important factor that can influence a company’s ability to adjust its cash holdings, especially since family businesses have certain advantages related to family ownership, such as family dedication, commitment to the business and the interaction between ownership and management. From this reasoning we propose that:

P2c: In a situation of economic crisis, family businesses will less use of downsizing mechanisms than non-family businesses.

5. Discussion and Implications

Our model draws on different approaches to emphasize the mechanisms through which family firms can consume the exceeding resources to buffer environmental jolts. Following prior research, we assume that slack resources moderate the effect of external crisis by means of its consumption or redeployment through different bias. Although organizational slack has been considered as a form of inefficiency on the lens of those researches that have used the agency theory, it cannot be denied that most literature has seen the possession of these types of resources as having a positive effect on firms proactive behavior and performance (Daniel et al., 2004).

It has been considered by the literature that family firms are expected to preserve an amount of organizational slack in case they need to face a crisis (Campopiano et al., 2019; Van Essen et al., 2015), but, how can this excess of resources be used has received little attention (Agusti et al., in press). It is not thus having the means not only to absorb the environmental jolt but also to react to this. Indeed, studies on slack resources have mainly considered the availability of these types of resources rather than how they are used when the environment becomes particularly hostile (Voss et al., 2008; Zona, 2012).

An environmental jolt or an economic downturn may become a critical challenge for the survival of most firms. When facing such a situation, firms may apply or consume the resources they have been accumulating along economic prosperity periods. In our model we take a look at the particularities of family firms when deciding which way of consumption may they use as they face an external crisis. Campopiano et al. (2019) remarked that the family firm is a particularly resilient form of organization. However, the difference in goal settings, financial and non-financial, and the risk-taking behavior associated to socioemotional wealth will reduce the flexibility and diversity of actions that can be taken to respond to a reduction of the environmental munificence associated to these situations.

Our study, summarized in our model, remarks the possible effects that the familiness character of the company may have in future performance. Against the work by Campopiano et al. (2019), slack does not play a mediating role but a key role in the decision making when facing a crisis situation.

However, this work is just an initial framework that needs further development. In this sense, a general consensus distinguishes three types of slack, namely available slack, recoverable slack and potential slack. Thus, while the former encompasses resources that have not been allocated to a specific task and can be used quickly for any purpose, recoverable requires time for its redeployment. Finally, potential slack is associated with the organisation’s ability to generate additional resources. Each of them present notable differences between family and non-family firms that will affect not only their accumulation but also their possibilities of application and operationalisation. A closer look to this problem by means.

The results of the application of our study may not only be of interest to the academic community but also to practitioners that can learn whether if it is convenient to save resources for difficult times or is it better to put the emphasis on efficiency and scarcity (Agusti et al., in press).

6. Conclusion

Slack resources are of critical importance for understanding a firm’s behaviour when facing an environmental jolt or a crisis situation. However, the type of ownership, and in particular if this is held within a family, must be considered for possible implications. Previous studies have analysed the effect of the availability of these resources to performance or innovation variables. However, less have dealt with the consumption, reduction or application of certain slack resources and how these processes relate to different outputs. Thus, these studies analyse whether a sudden reduction in slack has any impact on innovation (Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2010), or whether a greater or lesser reduction in costs and assets in a retrenchment process favours the survival of the company and the turnaround process (Barker & Mone, 1994; Robbins & Pearce, 1992). Studies on liquidity in crisis situations analyse how firms manage the different sources of finance available to them (Campello et al., 2011), linking this management to the survival or maintenance of the firm’s profitability (Cheng & Kesner, 1997; Deb et al., 2017; Paeleman & Vanacker, 2015). By considering the specific objectives and decision-making processes associated to family firms we enrich the debate around the usefulness of slack resources in uncertain situations, such as environmental jolts or economic downturns, and the effect of their usage or redeployment in the pursuit of survival or performance. This work aims to make a plea for more research on how family firms accumulate, adjust and redeploy the different resources, and in particular those that do not respond to an efficiency perspective. It is therefore necessary to empirically test the different propositions set in this paper. Furthermore, understanding how the different levels of familiness affect this consume, or the mediating effect of some variables, such as the socio-economic wealth, emerge as important research lines for the future.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the research group GIRCO (Grupo de Investigación sobre Recursos y Capacidades Organizativas), funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (grant no. ECO2017-84364-R).

References

Aaker, D. A., & Mascarenhas, B. (1984). The need for strategic flexibility. The Journal of Business Strategy, 5(2), 74-82. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039060

Agarwal, R., Barney, J. B., Foss, N. J., & Klein, P. G. (2009). Heterogeneous resources and the financial crisis: implications of strategic management theory. Strategic Organization, 7(4), 467-484. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127009346790

Agusti, M., Galan, J. L., & Acedo, F. J. (2020, in press). Saving for the bad times: slack resources during an economic downturn. Journal of Business Strategy. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-05-2020-0099

Alessandri, T. M., Cerrato, D., & Eddleston, K. A. (2018). The mixed gamble of internationalization in family and nonfamily firms: the moderating role of organizational slack. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 46-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1201

Amato, S., Basco, R., Ansón, S. G., & Lattanzi, N. (2020). Family-managed firms and employment growth during an economic downturn: does their location matter? Baltic Journal of Management, 15(4), 607-630. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-07-2019-0260

Argilés-Bosch, J. M., Garcia-Blandón, J., Ravenda, D., & Martinez-Blasco, M. (2018). An empirical analysis of the curvilinear relationship between slack and firm performance. Journal of Management Control, 29(3/4), 361-397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-018-0270-4

Arslan-Ayaydin, Ö., Florackis, C., & Ozkan, A. (2014). Financial flexibility, corporate investment and performance: evidence from financial crises. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 42(2), 211-250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-012-0340-x

Barker III, V. L., & Mone, M. A. (1994). Retrenchment: cause of turnaround and consequence of decline? Strategic Management Journal, 15(5), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150506

Basly, S., & Saadi, T. (2020). The value relevance of accounting performance measures for quoted family firms: a study in the light of the alignment and entrenchment hypotheses. European Journal of Family Business, 10(2), 6-23. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i2.7397

Bentley, F. S., & Kehoe R. R. (2020). Give them some slack—They’re trying to change! The benefits of excess cash, excess employees, and increased human capital in the strategic change context. Academy of Management Journal, 63(1), 181-204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0272

Block, J. (2010). Family management, family ownership, and downsizing: evidence from S&P 500 firms. Family Business Review, 23(2), 109-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/089448651002300202

Bourgeois, L. J. (1981). On the measurement of organizational slack. Academy of Management Review, 6(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4287985

Boyne, G. A., & Meier, K. J. (2009). Environmental change, human resources and organizational turnaround. Journal of Management Studies, 46(5), 835-863.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00813.x

Bradley, S. W., Shepherd, D. A., & Wiklund, J. (2011).The importance of slack for new organizations facing ‘tough’ environments. Journal of Management Studies, 48(5), 1071–1097. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00906.x

Brush, T. H., Bromiley, P., & Hendrickx, M. (2000). The free cash flow hypothesis for sales growth and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 455-472. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200004)21:4<455::AID-SMJ83>3.0.CO;2-P

Campello, M., Giambona, E., Graham, J. R., & Harvey, C. R. (2011). Liquidity management and corporate investment during a financial crisis. The Review of Financial Studies, 24(6), 1944–1979. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq131

Campopiano G., De Massis A., & Kotlar J. (2019). Environmental jolts, family-centered non-economic goals, and innovation: a framework of family firm resilience. In: E. Memili, & C. Dibrell (eds). The Palgrave Handbook of Heterogeneity among Family Firms. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77676-7_28

Casillas, J. C., Barbero, J. L., & Moreno, A. M. (2013). Reestructuración y tipo de propiedad en empresas en crisis. Diferencias entre empresas familiares y no familiares. European Journal of Family Business, 3(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v3i1.4037

Casillas, J. C., Moreno, A. M., & Barbero, J. L. (2010). A configurational approach of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth of family firms. Family Business Review, 23(1), 27-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486509345159

Cennamo, C., Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez–Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: why family–controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(6), 1153-1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00543.x

Chen, C. J., Hsiao, Y. C., Chu, M. A., & Hu, K. K. (2015). The relationship between team diversity and new product performance: the moderating role of organizational slack. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 62(4), 568-577. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2015.2458891

Cheng, J., & Kesner, I. (1997). Organizational slack and response to environmental shifts: the impact of resource allocation patterns. Journal of Management, 23(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300101

Chrisman, J., & Patel, P. (2012). Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 976-997. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0211

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1956). Organizational factors in the theory of oligopoly. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 44-64. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884512

Daniel, F., Lohrke, F. T., Fornaciari, C. J., & Turner, R. A. (2004). Slack resources and firm performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research, 57(6), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00439-3

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Majocchi, A., & Piscitello, L. (2018). Family firms in the global economy: toward a deeper understanding of internationalization determinants, processes, and outcomes. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1199

Deb, P., David, P., & O’Brien, J. (2017). When is cash good or bad for firm performance? Strategic Management Journal, 38(2), 436-454. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2486

Dewitt, R. L. (1998). Firm, industry, and strategy influences on choice of downsizing approach. Strategic Management Journal, 19(1), 59-79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3094180

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504-1511. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2632235

Donada, C., & Dostaler, I. (2005). Relational antecedents of organizational slack: an empirical study into supplier-customer relationships. M@n@gement, 8(2), 25-46. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.082.0025

Dougherty, D., & Bowman, E. H. (1995). The effects of organizational downsizing on product innovation. California Management Review, 37(4), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165809

Evans, J. S. (1991). Strategic flexibility for high technology manoeuvres: a conceptual framework. Journal of Management Studies, 28(1), 69-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1991.tb00271.x

Ferrari, F. (2019). Does too much love hinder innovation? Family involvement and firms’ innovativeness in family-owned small medium enterprises (SMEs). European Journal of Family Business, 9(2), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v9i2.5388

Fiegenbaum, A., & Karnani, A. (1991). Output flexibility—A competitive advantage for small firms. Strategic Management Journal, 12(2), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120203

Francis, J. D., & Pett, T. L. (2004). Retrenchment in declining organizations: towards an integrative understanding. Journal of Business and Management, 10(1), 39-52.

Geiger, S. W., & Cashen, L. H. (2002). A multidimensional examination of slack and its impact on innovation. Journal of Managerial Issues, 14(1), 68-84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604374

George, G. (2005). Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 661–676. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17843944

Godoy‐Bejarano, J. M., Ruiz‐Pava, G. A., & Téllez‐Falla, D. F. (2020). Environmental complexity, slack, and firm performance. Journal of Business Economics, 112, 105933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2020.105933.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653-707. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

Gral, B. (2014). How financial slack affects corporate performance: an examination in an uncertain and resource scarce environment. Springer Science & Business Media.

Guthrie, J. P., & Datta, D. K. (2008). Dumb and dumber: the impact of downsizing on firm performance as moderated by industry conditions. Organization Science, 19(1), 108-123. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0298

Hardin, W. G., Highfield, M. J., Hill, M. D., & Kelly, G. W. (2009). The determinants of REIT cash holdings. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 39(1), 39-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9103-1

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency cost of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review, 76(2), 323–329.

Jung, C., Foege, J. N., & Nüesch, S. (2020). Cash for contingencies: how the organizational task environment shapes the cash-performance relationship. Long Range Planning, 53(3), 101885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.05.005

Karacay, M. (2017). Slack-performance relationship before, during and after a financial crisis: empirical evidence from European manufacturing firms. Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Kellermanns, F. W. (2005). Family firm resource management: commentary and extensions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 313-319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00085.x

Kim, C., & Bettis, R. A. (2014). Cash is surprisingly valuable as a strategic asset. Strategic Management Journal, 35(13), 2053-2063. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2205

Kim, H., Kim, H., & Lee, P. M. (2008). Ownership structure and the relationship between financial slack and R&D investments: evidence from Korean firms. Organization Science, 19(3), 404-418. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25146190

Kim, Y., & Ployhart, R. E. (2014). The effects of staffing and training on firm productivity and profit growth before, during and after the great recession. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(3), 361-389. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035408

Klingebiel, R., & Adner, R. (2015). Real options logic revisited: the performance effects of alternative resource allocation regimes. Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 221-241. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0703

Kotlar, J., & De Massis, A. (2013). Goal setting in family firms: goal diversity, social interactions, and collective commitment to family–centered goals. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1263-1288. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12065

Kulkarni, S. P., & Ramamoorthy, N. (2005). Commitment, flexibility and the choice of employment contracts. Human Relations, 58(6), 741-761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726705057170

Laffranchini, G., & Braun, M. (2014). Slack in family firms: evidence from Italy (2006-2010). Journal of Family Business Management, 4(2), 171-193. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-04-2013-0011

Latham, S. F., & Braun, M. R. (2008). The performance implications of financial slack during economic recession and recovery: observations from the software industry (2001-2003). Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(1), 30-50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604593

Latham, S. F., & Braun, M. (2009). Assessing the relationship between financial slack and company performance during an economic recession: an empirical study. International Journal of Management, 26(1), 33-40.

Lavie, D. (2012). The case for a process theory of resource accumulation and deployment. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 316-323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127012452822

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organization Science, 22(3), 704-721. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0541

Lee, J. (2006). Family firm performance: further evidence. Family Business Review, 19(2), 103-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00060.x

Lim, D. S., Celly, N., Morse, E. A., & Rowe, W. G. (2013). Rethinking the effectiveness of asset and cost retrenchment: the contingency effects of a firm’s rent creation mechanism. Strategic Management Journal, 34(1), 42-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1996

Lim, E. N., & Mccann, B. T. (2013). The influence of relative values of outside director stock options on firm strategic risk from a multiagent perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 34(13), 1568-1590. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2088

Liu, Y., Chen, Y. J., & Wang, L. C. (2017). Family business, innovation and organizational slack in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(1), 193-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9496-6

Liu, Y., Lin, W. T., & Cheng, K. Y. (2011). Family ownership and the international involvement of Taiwan’s high-technology firms: the moderating effect of high-discretion organizational slack. Management and Organization Review, 7(2), 201-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00220.x

Lorenzo-Gómez, J. D. (2020). Barriers to change in family businesses. European Journal of Family Business, 10(1), 54-63. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i1.7018

Love, E. G., & Nohria, N. (2005). Reducing slack: the performance consequences of downsizing by large industrial firms, 1977-93. Strategic Management Journal, 26(12), 1087-1108. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.487

Lozano, M. B. (2015). Strategic decisions of family firms on cash accumulation. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 55(4), 461-466. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020150409

Machek, O. (2017). Employee compensation and job security in family firms: evidence from the Czech Republic. Journal for East European Management Studies, 22(3), 362-373. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44507677

Mahto, R. V., & Khanin, D. (2015). Satisfaction with past financial performance, risk taking, and future performance expectations in the family business. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(3), 801-818. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12088

Marlin, D., & Geiger, S. W. (2015). A reexamination of the organizational slack and innovation relationship. Journal of Business Research, 68(12), 2683–2690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.03.047

Meier, I., Bozec, Y., & Laurin, C. (2013). Financial flexibility and the performance during the recent financial crisis. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 23(2), 79-96.https://doi.org/10.1108/10569211311324894

Mellahi, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2010). A study of the association between level of slack reduction following downsizing and innovation output. Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 483–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00872.x

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Lester, R.H. (2012). Family firm governance, strategic conformity, and performance: institutional vs strategic perspectives. Organization Science, 24(1), 189-209. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0728

Miller, D., Le Breton‐Miller, I., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Family and lone founder ownership and strategic behaviour: social context, identity, and institutional logics. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00896.x

Morrow Jr, J. L., Johnson, R. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2004). The effects of cost and asset retrenchment on firm performance: the overlooked role of a firm’s competitive environment. Journal of Management, 30(2), 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.01.002

Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have (No. w1396). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Nadkarni, S., & Narayanan, V. K. (2007). Strategic schemas, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: the moderating role of industry clockspeed. Strategic Management Journal, 28(3), 243-270. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.576

Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00082.x

Namiki, N. (2013). The impact of slack reduction on performance turnaround during the Great Recession: the case of US electronics companies. Rikkyo Rusiness Review, 6, 56-62. http://doi.org/10.14992/00009836

Namiki, N. (2015). The role of slack reduction on performance turnaround during the Great Recession: the case of Japanese machinery companies. Rikkyo Rusiness Review, 8, 74-80. http://doi.org/10.14992/00012369

Namiki, N. (2016). Financial slack, financial slack reduction and firm performance during the Great Recession: the case of small-sized Japanese electronics companies. Rikkyo Rusiness Review, 9, 3-12. http://doi.org/10.14992/00012391

Nason, R. S., & Patel, P. C. (2016). Is cash king? Market performance and cash during a recession. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 4242-4248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.001

Nordqvist, M., & Melin, L. (2010). Entrepreneurial families and family firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22(3-4), 211-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985621003726119

Nordqvist, M., Habbershon, T. G., & Melin, L. (2008). Transgenerational entrepreneurship: exploring entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. In H. Landström, D. Smallbone, H. Crijns, & E. Laveren (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, sustainable growth and performance: Frontiers in European entrepreneurship research (pp. 93–116). London: Edward Elgar.

Paeleman, I., & Vanacker, T. (2015). Less is more, or not? On the interplay between bundles of slack resources, firm performance and firm survival. Journal of Management Studies, 52(6), 819–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12135

Pindado, J., Requejo, I., & de la Torre, C. (2011). Family control and investment–cash flow sensitivity: Empirical evidence from the Euro zone. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(5), 1389-1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.07.003

Robbins, D. K., & Pearce, J. A. (1992). Turnaround: retrenchment and recovery. Strategic Management Journal, 13(4), 287-309. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130404

Sanchez, R. (1993). Strategic flexibility, firm organization, and managerial work in dynamic markets: a strategic options perspective. Advances in Strategic Management, 9(1), 251-291.

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., & Dino, R. N. (2002). Altruism, agency, and the competitiveness of family firms. Managerial and Decision Economics, 23(4/5) 247-259. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1064

Sharfman, M. P., Wolf, G., Chase, R. B., & Tansik, D. A. (1988). Antecedents of organizational slack. Academy of Management Review, 13(4), 601-614. https://doi.org/10.2307/258378

Sharma, P., & Manikutty, S. (2005). Strategic divestments in family firms: role of family structure and community culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 293-311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00084.x

Shimizu, K., & Hitt, M. A. (2004). Strategic flexibility: organizational preparedness to reverse ineffective strategic decisions. Academy of Management Perspectives, 18(4), 44-59. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.15268683

Stan, C., Peng, M., & Bruton, G. (2014). Slack and the performance of state-owned enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31, 473-495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-013-9347-7

Stavrou, E., Kassinis, G., & Filotheou, A. (2007). Downsizing and stakeholder orientation among the Fortune 500: does family ownership matter? Journal of Business Ethics, 72(2), 149-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9162-x

Su, Z., Xie, E., & Li, Y. (2009). Organizational slack and firm performance during institutional transitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(1), 75-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-008-9101-8

Tan, J., & Peng, M. W. (2003). Organizational slack and firm performance during economic transitions: Two studies from an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1249-1263. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.351

Tang, Y., Qian, C., Chen, G., & Shen, R. (2015). How CEO hubris affects corporate social (ir)responsibility. Strategic Management Journal, 36(9), 1338–1357. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2286

Thomas, E. F. (2013). Platform-based product design and environmental turbulence. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-06-2013-0055

Thompson, J. D. (1967). Organizations in action: social science bases of administrative theory. McGraw-Hill.

Tsang, E. W. K. (2006). Behavioral assumptions and theory development: the case of transaction cost economics. Strategic Management Journal, 7(11), 999-1011. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.553

Van Essen, M., Strike, V. M., Carney, M., & Sapp, S. (2015). The resilient family firm: stakeholder outcomes and institutional effects. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(3), 167–183.

Vanacker, T., Collewaert, V., & Zahra, S. A. (2017). Slack resources, firm performance, and the institutional context: evidence from privately held European firms. Strategic Management Journal, 38(6), 1305–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2583

Voss, G. B., Sirdeshmukh, D., & Voss, Z. G. (2008). The effects of slack resources and environmental threat on product exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 51(1), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.30767373

Wagan, T. H. (1998). Exploring the consequences of workforce reduction. Canadian Journal of Administrative Science, 15(4), 300-309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.1998.tb00172.x

Wenzel, M., Stanske, S., & Lieberman, M. B. (2020). Strategic responses to crisis. Strategic Management Journal, 42(2), 16-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3161

Wu, J., & Tu, R. (2007). CEO stock option pay and R&D spending: a behavioral agency explanation. Journal of Business Research, 60(5), 482-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.006

Xu, K., & Hitt, M. A. (2020). The international expansion of family firms: the moderating role of internal financial slack and external capital availability. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(1), 127-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9593-9

Zahra, S. A. (2005). Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Family Business Review, 18(1), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00028.x

Zahra, S. A. (2007). Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(3), 443-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.04.007

Zona, F. (2012). Corporate investing as a response to economic downturn: prospect theory, the behavioural agency model and the role of financial slack. British Journal of Management, 23(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00818.x