European Journal of Family Business (2022) 12, 1-12

Strategic Behavior of Zombie Companies: Differences Between Family and Non-Family Companies Listed in Mexico

Manuel Humberto de la Garza Cárdenasa*, Mariana Zerón Félixa,

Guadalupe del Carmen Briano Turrentb

aUniversidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, Ciudad Victoria, Mexico

bUniversidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí, Mexico

Research paper. Received: 2020-10-20; accepted: 2021-09-14

JEL CLASSIFICATION

L10

KEYWORDS

Family firms, Firm strategy, Logit panel data, Market structure, Zombie firms

CÓDIGOS JEL

L10

PALABRAS CLAVE

Empresa familiar, Empresa zombi, Estrategia empresarial, Estructura de mercado, Panel de datos logit

Abstract Zombie companies are organizations that receive preferential treatment and benefits from various institutions. In addition, they have a negative connotation since they affect the markets where they operate. To understand this type of company in Mexico, the influence of the type of business strategy on the probability of being a zombie company is analyzed. For this, a logit analysis was used to evaluate the probability of incurring in the zombie attribute, and a panel of 99 companies that were listed on the Mexican Stock Exchange during the period from 2013 to 2017 was adopted. The empirical result shows that the type of defensive strategy reduces the probability of incurring in the zombie situation. On the other hand, the type of analytical and proactive strategy shows a greater probability of being classified as zombie companies, which, a priori could surprise, however, the Latin American institutional environment favors that such behavior is prone to lead to the zombie situation. Regarding the family element, no significant differences are found between family and non-family businesses.

Comportamiento estratégico de las empresas Zombis: Diferencias entre empresas familiares y no familiares cotizadas en México

Resumen Las empresas zombis tienen una connotación negativa dado que afectan a los mercados en donde operan. Para entender este tipo de empresas en México, se analiza la influencia del tipo de estrategia empresarial en la probabilidad de ser empresa zombi. Para ello, se empleó un análisis logit para evaluar la probabilidad de incurrir en la característica zombi, se usó un panel de 99 empresas que cotizaron en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores durante el periodo de 2013 a 2017. El resultado empírico evidencia que el tipo de estrategia defensivo disminuye la probabilidad de incurrir en la situación zombi; por otro lado, lo tipos de estrategia analizador y proactivo muestran una mayor probabilidad en ser catalogadas como empresas zombis, lo que, a priori podría sorprender, sin embargo, el entorno institucional Latinoamericano favorece que dicho comportamiento sea propenso a derivar en la situación zombi.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v12i1.10528

Copyright 2022: Manuel Humberto de la Garza Cárdenasa, Mariana Zerón Félix, Guadalupe del Carmen Briano Turrent

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author:

E-mail: mdelagarza@uat.edu.mx

1. Introduction

The traditional economic view holds that financial markets are a reflection - in quality and quantity of instruments - of a country’s economic development (Schumpeter, 1934; Shaw, 2009). There are various problems and difficulties that companies face to survive or succeed, such as adapting to a changing environment (Rezazade & Lashkarbolouki, 2016), having adequate management and allocation of resources (Camacho et al., 2013), and making accurate decisions at the right time (Antia et al., 2010). These actions can cause the bankruptcy of a company, and it is of special interest to prevent companies from reaching that drastic point (Camacho et al., 2015; Campa & Camacho, 2014).

Some alternatives help to maintain the commercial operation of companies and avoid bankruptcy, such as government financing or protectionist policies that seek to make regulations more flexible, subsidies for the payment of taxes or the transfer of overvalued projects (Jiang et al., 2017). On the other hand, companies themselves can also carry out actions to prevent bankruptcy. For instance, using their commercial relationships to favor financial conditions with suppliers (Campa & Camacho 2014). The implementation of both types of actions is attractive, since the bankruptcy of a company entails the loss of jobs, the collection of less taxes, lower income for families and a decrease in the supply of products or services, among others (Camacho et al., 2013, 2015).

Companies that use alternative methods to maintain operation are known as zombie companies (McGowan et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2016). These units depend mainly on external actors, since their activities, resource management or operational performance is not enough to prosper (Uchida et al., 2015). Different authors have found zombie signatures in several countries such as Japan (Caballero et al., 2008), China (Shen & Chen 2017; Tan et al., 2016), Spain (Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2018), countries belonging to the OECD (McGowan et al., 2016) and other members of the European Community (Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2016); which shows the extent of its presence.

In the literature, these organizations have been traditionally identified under the criterion of using the subsidy in the payment of financial interest, either because they maintain a close relationship with financial institutions or because they cannot cover said cost (Caballero et al., 2008; Fukuda & Nakamura, 2011; Nakamura & Fukuda, 2013; Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2018). Authors such as Caballero et al. (2008), Hoshi (2006), Jiang et al. (2017), McGowan et al. (2016) and Shen and Chen (2017) have shown that zombie companies have adverse effects on the industries where they operate, therefore, interest in their study has increased. The negative effect is due to the fact that they saturate markets and limit the competitiveness of “non-zombie companies”, monopolizing productive factors such as labor and capital. However, this research will focus on internal causes, specifically the strategic operational activities that cause the zombie situation of each company (Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2016, 2018).

There are elements such as operational effectiveness or resource management that can block the achievement of the expected corporate results for companies (Kalak et al., 2017). Therefore, some previous research emphasizes how zombie companies carry out their activities, pointing out that these organizations are not exclusive to a region or economic condition (Iwaisako et al., 2013; Nakamura & Fukuda, 2013; Tan et al., 2016). The Latin American region offers a unique context in terms of organizational management that make this issue a more complicated case (Bianchi & Figueiredo, 2017; Hazera et al., 2016; Peters; 2016). In the particular case of Mexico, the adoption of good commercial and international practices is common compared to other more developed regions (Kemme & Koleyni, 2017; Peters, 2016). Vidal, Marshall and Correa (2011) prove that the fluctuation of the Mexican economy is related to the strength of financial markets and not because it is a “victim” of economic recessions of the world powers. For these reasons, the competitiveness of financial markets is essential to increase economic activity (Valdés & Roldán, 2016).

Latin American countries are characterized by a protectionist policy for foreign investors and the creation of entry barriers for new investors (Juárez et al., 2015; Silva & Chavez, 2002). In addition, there is a strong information asymmetry, a greater concentration of ownership and an incentive to extract private benefits, especially by family businesses (Briano-Turrent et al., 2020; Maquieira et al., 2012; Watkins & Flores, 2016). This last element marks similarities and differences between Mexican companies and those of the rest of the world. While they bear a similarity, at least in terms of the concentration of ownership with other Latin countries, they differ from the Anglo-Saxon ones, where the proportion of organizations controlled by a family is lower (Espinoza & Espinoza, 2012). This concentration of ownership, according to agency theory, may be one of the causes that lead organizations to divert resources towards the private benefit and not the collective one (Watkins, 2018).

Regarding family businesses, in Mexico there are a large number of family organizations within its business network; KPMG (2013) estimated that more than 90% of Mexican companies can be classified as family companies. While in the stock market, Watkins (2018) estimates an average of 77% of this type of companies between 2001 and 2015, where organizations such as América Móvil, CEMEX and Grupo Bimbo (controlled by the Slim, Zambrano and Servitje families respectively), stand out as examples of some of the largest companies in the country and even in Latin America (Ramírez-Solís et al., 2016). According to San-Jose, Urionabarrenetxea and García-Merino (2021), the concentration of ownership favors the zombie condition of listed companies.

The foregoing shows the interest in conducting the study in the Mexican environment, the main research objective being to identify the type of business strategy that make companies to be classified as zombies, and how the family element can favor this condition. In line with some authors such as Iwaisako et al. (2013) and Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2016, 2018) who find operational aspects as drivers of the zombie company, this article proposes to delve into the type of business strategy, which leads us to ask the following research questions: What type of business strategy leads companies to classify into the zombie condition? Does the concentration of shares in the hands of the family motivate a zombie condition in Mexican listed companies?

Considering the aforementioned, the research is carried out in a temporary space of economic stability, which allows the study to focus on the aspects of business management that, as mentioned, are peculiar in the region. In addition, the main contribution of this research is in the use of the type of strategy as a predictor of the zombie company, where various operational and administrative actions are considered; unlike previous investigations where some variables associated with the operation of an organization are used individually.

Authors such as Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal (2016), Caballero et al. (2008), Hoshi (2006), Iwaisako et al. (2013) and McGowan et al. (2016) were the first to study zombie companies, which is why they make up the main analysis environment. This framework defines zombie companies as organizations that receive strong external support to operate in the markets, such as the concession of taxes or overvalued projects or contracts, and in some extreme cases, they are safe from bankruptcy (Caballero et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2017; Shen & Chen, 2017). Other distinguished elements are high leverage, asset underutilization, and short-term financial planning (Imai, 2016; Urionabarrenetxea et al., 2016). Caballero et al. (2008) define a zombie company as an organization that receives some subsidy in its financing, not always because they have financial problems, but simply because they can access that benefit.

The literature on these companies is in early development and has focused on studying a group of zombie companies, their effect on industries, and the “contagion” of behavior to “healthy” companies. The authors have found negative effects on sectoral productivity, decreased competition, and misallocation of financial and human resources (Caballero et al., 2008; Shen & Chen, 2017). Another characteristic is that there are industries that favor the existence of zombie companies, mainly those that have a low level of competitiveness and high institutional regulation (Caballero et al., 2008). The first conclusions of the authors suggested that the cause of the existence of zombie companies was due to the competitive environment in which they were found.

Nakamura and Fukuda (2013) found that zombie companies “recovered” from the condition through restructuring of operations or changes in organizational form. The results helped the zombie literature to use the internal vision of the company, which made it more important to understand the individual unit. Recently, authors such as Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2018) have contributed to the analysis at company level, arguing that the root of the zombie condition is in aspects related to its structure and performance of operations.

Despite little development, the framework describes that among the operational actions that characterize zombie companies, in addition to the impossibility of using all their productive capacity (Shen & Chen, 2017), there is the inefficient allocation of human, material or financial resources (Andrews et al., 2016; Imai, 2016; McGowan et al., 2016; Shen & Chen, 2017). Therefore, it is intended to use an internal approach to shed light on the operational actions that lead a company to become a zombie.

These characteristics are part of the corporate culture that leads zombie companies to show particular actions in the markets (Caballero et al., 2008; Shen & Chen, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to explore their different corporate behaviors, their perceptions, as well as their preferences to determine some behavior patterns (Albertos & Kuo, 2018; Jaakkola & Hallin, 2018). A company adopts a strategic behavior through environmental perceptions, the characteristics of the industry, the competition and its capabilities (Bain, 1968; Rumelt et al., 1991; Shapiro, 1989). Each organization is defined by different internal elements, both formal and informal, which creates a structure in which activities interrelated with other similar practices take place (Hall & Saias, 1980).

For a company, the definition of a strategic behavior is discriminatory by nature (Caves, 1980; Miles et al., 1978), and it is rare that these decisions influence the actions or include the commitment of different human and financial resources and materials, among others (Eisenhardt & Zbaracki, 1992; Hambrick, 1983).

To determine the strategic behavior of zombie companies, the previous literature that associates these elements was reviewed. Regarding the strategic actions of the Proactive type, the study carried out by Nakamura and Fukuda (2013), attributes the condition of zombie to the adoption of an innovative strategic practice. Similarly, Shen and Chen (2017) argued that the use of technologies as a fundamental element in their strategic behavior puts the zombie condition at a disadvantage. It should be noted that Nakamura and Fukuda (2013) studied companies that were restructured, while Shen and Chen (2017) focused on studying industrial companies, so operational efficiency is a fundamental part of these. Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2018) anticipated that companies that base their operations on intangible assets are more likely to be zombie.

The researchers found this relationship, arguing that companies with this type of activity tend to have a greater demand for investment, as well as a greater risk in terms of the projects developed. This is because it is an essential part to be able to have various projects to seek a greater scope, which means that they must be flexible and have high coordination to be successful and, where appropriate, adapt to changing market conditions (Slater et al., 2011), however, this can mean difficulties in terms of efficient resource management and obtaining the best possible performance (Miles et al., 1978).

Jermias (2008) and Simerly and Li (2000) showed evidence that proactive companies are more likely to default on their financial obligations. The first study justifies that the activities of this type of companies are more uncertain. While the second finds that companies have a higher level of leverage with prospective strategies. Therefore, they face greater difficulties in fulfilling their responsibilities.

Lee (2013), by contrast, argues that R&D-related investments help an organization recover from zombie status. The empirical studies that relate strategic proactive behavior with zombie companies are limited, so literature referring to similar factors such as the amount of debt incurred and the probability of failure as variables related to zombie companies was analyzed (Jardim & Pereira, 2013). As evidenced, the empirical antecedents are contradictory, however, the specialized literature has a similar trend, which is why the following hypothesis is proposed:

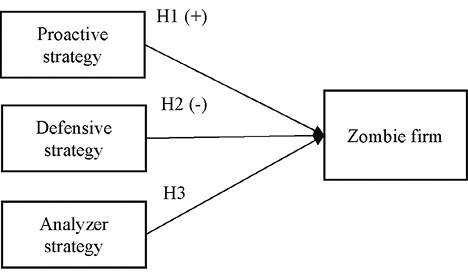

H1: The proactive type strategy increases the probability that the company is a zombie.

Regarding the type of defensive behavior, Nakamura and Fukuda (2013) and Shen and Chen (2017) empirically showed that these companies are less likely to be zombies. Even Nakamura and Fukuda (2013) argue that zombie companies must carry out an operational restructuring to be efficient and even eliminate idle assets.

This strategy seeks to control its resources (material, human and financial) to reduce costs, since the focus on the market must be profitable enough to be attractive to continue operating (Higgins et al., 2015), therefore and unlike the Proactive, this type of strategy favors effectiveness and, in financial matters, they are characterized by prioritizing the fulfillment of obligations, such as the payment of financing. This could favor the reduction of financial risk, bankruptcy and incurring in the zombie situation.

Likewise, the empirical evidence is limited, so the literature on bankruptcy and debt default was reviewed. Jermias (2008) and Rahimi (2016) provide empirical evidence on companies characterized by cautious behavior and that present a defensive strategy have higher levels of indebtedness, which is due to the fact that the debt claim requires efficiency to be able to attend to it. Regarding to the family firms context, the Socio Emotional Wealth (SEW) perspective emphasizes the role of non-economic goals, which may increase the risk aversion in order to transfer its legacy to the next generation (Moreno-Menéndez et al., 2021). In the same line, Rienda and Andreu (2021) suggest that family owners take advantages from the socio-emotional aspects of the business, choosing strategies that fulfil its motivations to preserve and enhance the SEW.

While Giovannetti, Ricchiuti and Velucchi (2011) found that companies that exploit small markets (defensive strategy) are more likely to fall into insolvency or bankruptcy, which explains the search for efficiency in their operations to improve their situation. On the other hand, Bentley-Goode et al. (2016) empirically argued that these types of companies have better control over their finances, so the probability of bankruptcy is lower.

According to the discussion previously presented, as well as with the inconsistency of the previous literature, the following hypothesis is established:

H2: The defensive type strategy decreases the probability that the company is a zombie one.

As mentioned above, the empirical evidence is limited, so it is difficult to present antecedents that help to support a hypothesis for the case of the Analyzer type of strategy, however, because it is a type of behavior that is among the Defensive and Proactive, the following hypothesis is proposed without direction:

H3: Analyzer-type strategy affects the probability that the company is a zombie one.

Next, Figure 1 is presented where the hypotheses of the investigation are summarized by means of a model.

Figure 1. Research model

3. Methodology

We selected the companies of the Mexican Stock Exchange (BMV), as the study subject of this research. The empirical study focused on the organizations that participated in the BMV between 2013 and 2017, a period in which 147 companies were registered in the capital market. The period covered by the research is characterized by having economic stability, which is favorable to the analysis of the effect of the study variables.

For the empirical study, organizations belonging to the financial sector were excluded, because financial information and its regulatory framework differ from other companies; which gives a total of 101 registered companies. Of which two did not publish their reports in any year, so the study considered 99 companies listed on the BMV. It is observed that about 31% belong to the Industrial sector, followed by Extraction of Materials with about 22%. Meanwhile, the Non-frequent consumer products sector has approximately 18% of the sample, the Telecommunications sector with 16% and, with a lower percentage, are the Frequent consumer products sector, the Health sector and the Energy sector with about 7%, 4% and 1%, respectively.

Additionally, family businesses were differentiated from non-family businesses considering whether the share ownership titles are in the hands of members of a single family, within the first group. Otherwise, they were considered as non-family businesses. According to the above, the sample has a total of 59 family businesses and 40 non-family businesses.

The level of non-payment of interest of each company (valuation of zombie companies) was determined by using the method proposed by Hoshi (2006), where the excess of the interest payment made by a company is estimated, with respect to the cost minimum debt (it will be deepened to the extent in the definition of variables section). Results showed that between 2013 and 2017, thirty-eight organizations distributed in the different sectors have been evaluated as zombie companies, as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Distribution of zombie companies by sector in the BMV |

||

|

Sector |

Zombie |

Total |

|

Industrial |

14 |

31 |

|

Material |

8 |

22 |

|

No frequent consumption |

7 |

18 |

|

Telecommunication |

4 |

6 |

|

Health sector |

2 |

4 |

|

Frequent consumption |

2 |

17 |

|

Energy |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

38 |

99 |

|

Source: self-made |

||

3.1. Definition of variables

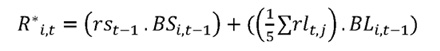

To categorize zombie companies, the ratio known as excess interest payment (EIR) developed by Hoshi (2006) was used. EIR represents the degree to which a company’s real interest payment (R) exceeds the required minimum (R*). For this case, R* represents a hypothetical cost of debt, which is based on a preferential interest defined by Caballero et al. (2008), such as:

[1]

[1]

Where BS is equal to short-term debt (less than one year) minus accounts receivable and taxes in favor; BL represents long-term debt (greater than one year); rs is the interest of the cost of the average short-term debt, while rl is the interest of the cost of the average long-term debt (for rl, the Treasury Certificates [CETES] were taken as reference, which are the debt instrument with the lowest cost).

After the R* calculation, EIR is determined by:

[2]

Using the formula, a value between -2 and 2 is obtained, where organizations with a negative EIR are classified as zombie companies, while non-zombies obtain a positive value. Therefore, the companies with a negative EIR were assigned to the zombie category (1), while those with a positive EIR were assigned to the non-zombie category (0).

According to Hoshi (2006), the mean is reliable in identifying zombie companies, having a minimal probability of making the mistake of classifying healthy companies as zombies. However, with the purpose of reducing this probability of error, it was decided to apply the criterion of Fukuda and Nakamura (2011) for the categorization of zombie companies, which consists of comparing the generation of profit with respect to the hypothetical interest, under the argument that a company capable of generating a gross profit to cover the cost of the debt could not be a zombie, in other words, when EBITDA > R* the company should be in the healthy category (0) despite having a negative EIR.

Regarding the determination of the type of strategy implemented by a company, the method of strategic classification by score used by Anwar and Hasnu (2016a, 2017) and Hambrick (1983) was selected. This method combines actions of a strategic nature and the degree of use by the companies analyzed, measured through the financial information published in the basic audited financial statements. Some of the actions include a focus on growth and sales, the degree of innovation and technology used, and productive efficiency. Table 2 summarizes the elements that make up the determination of the type of strategy, while Table 3 describes the measurement of each variable.

Once the indicators have been obtained, a quintile classification is carried out, which will serve to give a score to each dimension of the companies. The score is assigned based on the place occupied from 0 points for quintile 1 to 4 points for quintile 5. The classification criterion is based on the interpretation of each dimension evaluated (see Table 2).

|

Table 2. Dimensions of the business strategy |

||

|

Dimension |

Concepto |

Interpretation |

|

Orientation towards innovation |

The propensity of the company to innovate and the degree of market focus it employs. |

High value for proactive. Low value for defensive |

|

Production efficiency |

Relationship between production costs and finished products. |

High value for proactive. Low value for defensive |

|

Sales growth rate |

Approach to investment and expansion opportunities chosen by a company. |

High value for proactive. Low value for defensive |

|

Capital intensity rate |

Degree of efficiency in technological and engineering investments. |

Low value for proactive. High value for defensive |

|

Source: Anwar and Hasnu (2016a, 2016b, 2017) |

||

|

Table 3. Calculation of strategic actions |

||

|

Dimension |

Measure |

Interpretation |

|

Orientation towards innovation |

|

High value for proactive behavior / Low value for defensive behavior |

|

Production efficiency |

|

High value for proactive behavior / Low value for defensive behavior |

|

Sales growth rate |

|

High value for proactive behavior / Low value for defensive behavior |

|

Capital intensity rate |

|

Low value for proactive behavior / High value for defensive behavior |

|

Source: self-made based on the consulted authors |

||

Finally, the summation of the scores obtained in each strategic action is carried out and, depending on the final score, the business strategy is categorized. The criteria used to categorize a company are based on Anwar and Hasnu (2017) and Evans and Green (2000) and are the following: a score of 0 to 5 to categorize Defenders, from 6 to 10 for Analyzers, and Proactive obtained a score from 11 to 16. Thus, a categorical variable is obtained that identifies the type of strategy used by each company. The coding of the type of strategy resulted in Defender (1), Analyzer (2), Proactive (3) and Reactive (4).

3.2. Logit data panel model

A logistic panel data analysis was developed; according to Cameron and Trivedi (2010) in a strictly balanced panel, all variables present observations for each time involved in the study, that is, there are no missing data. Table 4 shows a general description of the panel, concluding that the research is composed of a short panel, with a cross section greater than the longitudinal one, that is, the group of observations is greater than the time series used (N > T).

|

Table 4. Dashboard summary |

|

|

Concept |

Report |

|

Panel type |

Strongly balanced panel |

|

Observations (N) |

99 firms |

|

Periods (T) |

5 years |

|

Tecnic |

Logit panel data |

|

Software |

Stata |

|

Source: self-made |

|

The data panel analysis allows us to run models with binary dependent variables, in this case, to measure the propensity of the proactive strategy in the probability that the organization is likely to be a zombie company and performs a binary logistic regression. The dependent variable is categorized if the company has the zombie condition (yes = 1, no = 0), and the independent variable corresponds to the category of the type of strategy that it implements (Defensive = 1, Analyzer = 2, and Proactive = 3).

4. Results

The statistical analysis was carried out in four models, in each model a type of strategy was set to observe the change in the probability that a company is a zombie one. Although each model shows similar information and may be redundant, it was decided to run them in order to show the variations in the effect of each type of strategy.

Thus, Model 1 uses the Defensive strategy; Model 2 uses the Analyzer; Model 3 uses the Proactive; and, finally, Model 4 uses the Reactive. All of them are used as fixed strategies. Table 5 shows that the models meet statistical significance, however, model 4 does not show significance in any of the strategies, so the analysis will focus on the first three models. In this way, the corresponding hypotheses can be contrasted.

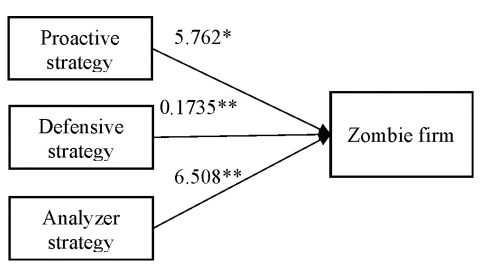

It can be observed, in the first model, that both the Analyzer (6.508) and Proactive (5.762) strategies increase the probability of being a zombie company, according to the odds ratio, the former being the one with the greatest effect. This shows that the Defensive strategy avoids falling into the zombie situation.

|

Table 5. Results of panel analysis of logit data |

||||||||

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

|

Odds ratio |

Std. error |

Odds ratio |

Std. error |

Odds ratio |

Std. error |

Odds ratio |

Std. error |

|

|

Defensive |

0.1735** |

0.1119 |

0.1735* |

0.1723 |

0.4443 |

0.7590 |

||

|

Analyzer |

6.508** |

4.7419 |

1.1294 |

0.8465 |

2.2891 |

2.8918 |

||

|

Proactive |

5.762* |

5.7211 |

0.8853 |

0.6635 |

2.5602 |

2.5602 |

||

|

Reactive |

2.25 |

3.8451 |

0.3458 |

0.5630 |

0.3905 |

0.6765 |

||

|

Age |

1.004 |

0.0036 |

1.0046 |

0.0036 |

1.0046 |

0.0036 |

1.004 |

0.0036 |

|

Size |

0.7961* |

0.1001 |

0.7961* |

0.1001 |

0.7961* |

0.1001 |

0.7961* |

0.1001 |

|

Profitability |

0.2048** |

0.1512 |

0.2048 |

0.1512 |

0.2048** |

0.1512 |

0.2048** |

0.1512 |

|

Wald chi2 |

14.57 |

14.57 |

14.57 |

14.57 |

||||

|

Sig. |

0.0239 |

0.0239 |

0.0239 |

0.0239 |

||||

|

Log likelihood |

-176.0192 |

-176.0192 |

-176.0192 |

-176.0192 |

||||

|

Note: * 0.1 significance level, ** 0.05 significance level, *** 0.01 significance level. Std. error= Standard error. |

||||||||

Model 2 shows that both the Defensive and Proactive strategies decrease the probability of being a zombie company, with respect to the Analyzer strategy. This evidence should be taken with caution, because only the Defensive strategy shows statistical significance. In other words, the result shows that only this type of strategy decreases the probability of being a zombie company.

Finally, Model 3, which compares the effect of the types of strategy with respect to the Proactive strategy, confirms the Defensive as the type of strategy that reduces the zombie situation. Although it shows that the type of analytical strategy increases the probability, it does not have statistical significance, so this effect cannot be assured (Bain, 1968; Rumelt et al., 1991; Shapiro, 1989). The Proactive strategy shows a contribution to the probability of incurring into the zombie situation. Models 1 and 4 show an increase in probability in the zombie situation, and model 2 shows a decrease in probability compared to the Analyzer, however, the odds ratio is higher than the rest of the strategies. The foregoing gives reason to support H1, although it should be noted that only one of the models shows statistical significance.

On the other hand, the results of the various models agree that the defensive strategy type has a lower contribution to the zombie situation, it even decreases that probability, maintaining statistical significance in two of the models, which is why the H2 is supported. Finally, the Analyzer-type strategy shows a contribution to the zombie situation, even presenting statistical significance in some cases. For this reason, it can be affirmed that this type of strategy contributes to a greater extent to the zombie problem, that is, the H3 is supported, remembering that a specific direction was not anticipated.

Figure 2. Research model, with the results of the empirical analysis. Odds ratio and corresponding significance are shown

In summary, Figure 2 shows that the Proactive strategy increases the probability of being a zombie company (H1); the Defensive Strategy decreases the probability of being a zombie company (H2); and, finally, the Analyzing Strategy has a significant effect (H3), adding that it does so, increasing the probability of being a zombie company.

Additionally, to complement the previous empirical analysis, as well as to give greater robustness to the study, a multiple regression analysis was carried out using the metric variables for the classification of zombie companies (EIR) and the strategic score to determine the type of strategy of the companies, adding the variables of year and industry (Table 6).

|

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis |

|||

|

EIR |

Coef. |

Std. Error |

Sig. |

|

Strategy |

-0.0347 |

0.0163 |

0.034** |

|

Age |

-0.0008 |

0.0004 |

0.069* |

|

Size |

0.0090 |

0.0186 |

0.629 |

|

Profitability |

0.2254 |

0.0950 |

0.018** |

|

Constant |

0.3784 |

0.3420 |

0.269 |

|

R2 |

0.0281 |

||

|

F |

3.54** |

||

|

Note: * significance at 10%; ** significance at 5%; significance at 1% Std. error= Standard error. |

|||

The results show a significant model and with a similar relationship to the logit model. Remembering that the dependent variable is negative for the zombie company, it can be interpreted that, as a strategy tends to be Proactive, the zombie situation will be deeper, because the variable shows a negative and significant coefficient.

To integrate the family element into the analysis, two ANOVA tests were performed, considering family businesses and non-family businesses the two groups to contrast. Meanwhile, the EIR measure of the zombie company and the Strategic Rating were the variables to be compared. Table 7 reports the results of the analysis.

|

Table 7. Analysis of variance, family businesses and non-family businesses |

||||

|

Groups |

Variable: zombie firm |

|||

|

Firms |

Mean |

F |

Sig. |

|

|

Family business |

59 |

0.346 |

0.16 |

0.6888 |

|

Non-family business |

40 |

0.309 |

||

|

Groups |

Variable: Strategy |

|||

|

Firms |

Media |

F |

Sig. |

|

|

Family business |

59 |

8.49 |

0.04 |

0.8419 |

|

Non-family business |

40 |

8.545 |

||

|

Note: * significance at 10%; ** significance at 5%; significance at 1% |

||||

As evidenced in the Table 7, no significant difference is identified between family and non-family companies in terms of zombie companies, which leads us to conclude that, regardless of the level of shareholding concentration in the hands of the family, it does not affect as a zombie company. Similarly, no differences are reported between family businesses and non-family businesses considering business strategy. Denoting that both groups of companies are homogeneous for the variables used.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The study fulfills the objective of analyzing the effect of the type of business strategy in zombie companies, discriminating between family and non-family companies. The results show that adopting a defensive strategy decreases the probability of being a zombie company. It is even shown that this strategy is the most effective to avoid incurring into the zombie situation. This coincides with the evidence provided by Nakamura and Fukuda (2013), Shen and Chen (2017) and Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2018).

It should be noted that Nakamura and Fukuda (2013) studied companies that were in a stage of restructuring their business. They prioritized the reduction of inactive fixed assets and the reduction of personnel through the implementation of these actions; therefore, they left the zombie condition by adopting behaviors associated with the type of defensive strategy. On the other hand, Shen and Chen (2017) found that, in China, many manufacturing companies were working, underusing their productive capacity, so that companies that used operational efficiency were performing better than zombie companies.

Using a sample of manufacturing companies may ensure that operational excellence (defensive or analytical strategy) can deliver better results than possible, under certain conditions. However, Urionabarrenetxea et al. (2018) used a broad spectrum of companies and concluded that those that base their operations on intangible assets are more likely to be zombie companies.

It should be remembered that companies in Mexico have distinctive characteristics in terms of ownership, such as being a family business, an information management company, a business practices one. Therefore, it is convenient to study the literature on business strategy, since it does not highlight one type of strategy over another one (except the reactive strategy), but the result is based on whether the company implemented any strategy correctly. In this case, there will be the same probability of success against the stimulus of the market and the capacities of the organization itself, regardless of the type of strategy implemented (Miles et al., 1978). Hence, the explanation about the effect of each type of strategy on the zombie company is in the way in which they implement the strategy and not in the strategy itself.

Taking into account the previous argument, it is necessary to refer to some characteristics of the environment. The company builds its structure and behavior according to its best conditions to survive or succeed (Bain, 1968; Rumelt et al., 1991; Shapiro, 1989), how the dynamic and global environment of markets, new technologies and the emergence of new business models complicate the development of companies, and Latin America is no exception (Bianchi et al., 2018).

Therefore, a concern about the competitiveness of companies in emerging economies, particularly in Latin American countries, is a central point, both for the academia and for government institutions in these places (Bianchi et al., 2018), including it in national policies and government agendas, making it a central issue (Albornoz, 2013; Ledur & Carvalho, 2006).

Bradshaw (2017) provides an example of this, explaining that the Brazilian government implemented regulatory reforms aimed at modernizing the energy sector, allowing innovation to prosper as good business practice. Likewise, Mojica (2010) explains that in countries such as Chile, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico they have organizations or institutions focused on improving the development or implementation of innovations, both for organizations and companies.

Given the empirical results, we suggest that the promotion and policies for the adoption of behaviors focused on innovation or technology is not adequate, in addition that organizations are not prepared, both structurally and organizationally, to develop an effective strategy. Thus, adding the institutional interest in promoting innovation and technology, plus the failed implementation of the proactive strategy, means that different agencies have to support the operations of the companies to avoid their bankruptcy. This could explain why a type of Proactive strategy increases the probability of incurring into the zombie situation.

Returning to the concentration of ownership, specifically on family businesses, no significant differences were found with respect to non-family ones, considering the zombie variable and the strategy variable. However, considering that a strategy alone does not improve or worsen the results, it should be noted that the generation of the zombie problem could be the result of privileging the family interests and not those of the organization, which would suppose an agency problem. Furthermore, taking into account that more than most of the BMV companies are family-owned (Espinoza & Espinoza, 2012; KPMG, 2013;

Ramírez-Solís et al., 2016), the global empirical results suggest that family-owned companies that have a type of defensive strategy decrease the probability of being a zombie, unlike the type of analytical and proactive strategy.

On the other hand, it is necessary to point out that authors such as Caballero et al. (2008), Hoshi (2006), Imai (2016) and McGowan et al. (2016) found that there are industries with a greater propensity for zombie companies, such as the construction, real estate, insurance and financial sectors, to name a few. In Mexico, in addition to finding zombie companies in the industrial sector, a recurrence of zombie companies was also found in sectors such as mineral extraction, infrastructure developers, passenger air transport companies and telecommunications companies.

Consequently, the presence of zombie companies in such industries may be due to the need for economic operators to facilitate the provision of necessary products or services within economies. It is not intended, with this study, to maintain that zombie companies are “a necessary evil”, but rather that the figure of the zombie company can be a figure adopted to survive under certain conditions, due to the need for its product or service to maintain the economic activity. With the COVID 19 pandemic, zombie companies worldwide have increased, so it is necessary for the family business to implement strategies to avoid falling into this condition, which puts their survival at risk.

This work opens the debate on the existence of different types of zombie companies. As a future line of research, it is proposed to analyze whether there are differences between these companies, both in their characteristics and in their behavior, which would imply new fields of research. Also, it is proposed to extend this study to other countries in the region to find similarities or differences. On the other hand, it would be convenient to add other types of variables that represent the effect exerted by the industry in which each company operates, because, according to the literature, it is an important element. In addition, it is suggested to extend this line of research, including the analysis of variables related to corporate governance, such as composition of the board of directors (size, independence, gender, duality), support committees of the board, characteristics of the CEO, among others.

Regarding the limitations of the research, it must be considered that it corresponds to a group of companies that are listed on a stock market and do not represent all of the business units in the country, so it would be convenient to study this phenomenon in other types of companies.

Finally, the article concludes that zombie companies in Mexico differ from other contexts, since the particular conditions of the environment offer different mechanisms for the development of organizations. A priori, it can be thought that a proactive or analytical company is far from the initial description of the zombie company. However, both the lack of implementation of the business strategy and the institutional tendency to promote this type of behavior, regardless of the purpose, are more elements in the formation of a zombie company.

References

Albertos, J. F., & Kuo, A. (2018). The structure of business preferences and Eurozone crisis policies. Business and Politics, 20(2), 165–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2017.35

Albornoz, M. (2013). Innovación, equidad y desarrollo latinoamericano. Isegoría, 0(48), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.3989/isegoria.2013.048.06

Andrews, D., Criscuolo, C., & Gal, P. (2016). The best versus the rest: the global productivity slowdown, divergence across firms and the role of public policy. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Antia, M., Pantzalis, C., & Park, J. C. (2010). CEO decision horizon and firm performance: an empirical investigation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(3), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.01.005

Anwar, J., & Hasnu, S. A. F. (2016a). Business strategy and firm performance: a multi-industry analysis. Journal of Strategy and Management, 9(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-09-2015-0071

Anwar, J., & Hasnu, S. A. F. (2016b). Strategy-performance linkage: methodological refinements and empirical analysis. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 10(3), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-07-2015-0096

Anwar, J., & Hasnu, S. A. F. (2017). Strategy-performance relationships: a comparative analysis of pure, hybrid, and reactor strategies. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 14(4), 446–465. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-07-2016-0056

Bain, J. (1968). Industrial organization. (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Bentley-Goode, K., Newton, N., & Thompson, A. (2016). Business strategy and internal control over financial reporting (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2637688). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2637688

Bianchi, C. G., & Figueiredo, J. C. B. de (2017). Characteristics of Brazilian scientific research on diffusion of innovations in business administration. RAI Revista de Administração e Inovação, 14(4), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rai.2017.07.004

Bradshaw, A. (2017). Regulatory change and innovation in Latin America: the case of renewable energy in Brazil. Utilities Policy, 49, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2017.01.006

Briano-Turrent, G. C., Watkins-Fassler, K., & Puente-Esparza, M. L. (2020). The Effect of the board composition on dividends: the case of Brazilian and Chilean family firms. European Journal of Family Business, 10(2), 43-60.https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i2.10177

Caballero, R., Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. (2008). Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1943–1977. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.5.1943

Camacho, M., Pascual, D., & Urquia, E. (2013). On the efficiency of bankruptcy law: empirical evidence in Spain. International Insolvency Review, 22(3), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/iir.1210

Camacho, M., Segovia, M., & Pascual, D. (2015). Which characteristics predict the survival of insolvent firms? An SME reorganization prediction model. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12076

Cameron, A., & Trivedi, P. (2010). Microeconometrics using Stata (Revised). Stata Press.

Campa, D., & Camacho, M. (2014). Earnings management among bankrupt non-listed firms: evidence from Spain. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting - Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 43(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02102412.2014.890820

Caves, R. (1980). Industrial organization, corporate strategy and structure. Journal of Economic Literature, 18(1), 64–92.

Eisenhardt, K., & Zbaracki, M. (1992). Strategic decision making. Strategic Management Journal, 13(52), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130904

Espinoza, T., & Espinoza, N. (2012). Family business performance: evidence from Mexico. Cuadernos de Administración, 25(44), 39-61.

Evans, J., & Green, C. (2000). Marketing strategy, constituent influence, and resource allocation: an application of the Miles and Snow typology to closely held firms in chapter 11 bankruptcy. Journal of Business Research, 50(2), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00036-3

Fukuda, S., & Nakamura, J. (2011). Why did “Zombie” firms recover in Japan? World Economy, 34(7), 1124–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2011.01368.x

Giovannetti, G., Ricchiuti, G., & Velucchi, M. (2011). Size, innovation and internationalization: a survival analysis of Italian firms. Applied Economics, 43(12), 1511–1520. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840802600566

Hall, D. J., & Saias, M. A. (1980). Strategy follows structure! Strategic Management Journal, 1(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250010205

Hambrick, D. (1983). Some tests of the effectiveness and functional attributes of Miles and Snow’s strategic types. Academy of Management Journal, 26(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/256132

Hazera, A., Quirvan, C., & Marin-Hernandez, S. (2016). The impact of guaranteed bailout assistance on bank loan overstatement: the Mexican financial crisis of the late 1990s and early 2000s. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12(2), 177–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-04-2014-0046

Higgins, D., Omer, T., & Phillips, J. (2015). The influence of a firm’s business strategy on its tax aggressiveness. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(2), 674–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12087

Hoshi, T. (2006). Economics of the living dead. Japanese Economic Review, 57(1), 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5876.2006.00354.x

Imai, K. (2016). A panel study of zombie SMEs in Japan: identification, borrowing and investment behavior. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 39, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2015.12.001

Iwaisako, T., Fukuoka, C., & Kanou, T. (2013). Debt restructuring of Japanese corporations: efficiency of factor allocations and the debt-labor complementarity. Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, 54(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.15057/25775

Jaakkola, E., & Hallin, A. (2018). Organizational structures for new service development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12399

Jardim, C., & Pereira, E. (2013). Corporate Bankruptcy of Portuguese firms. Zagreb International Review of Economics and Business, 16(2), 39-56.

Jermias, J. (2008). The relative influence of competitive intensity and business strategy on the relationship between financial leverage and performance. The British Accounting Review, 40(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2007.11.001

Jiang, X., Li, S., & Song, X. (2017). The mystery of zombie enterprises – “stiff but deathless”. China Journal of Accounting Research, 10(4), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2017.08.001

Juárez, G. de la L., Sánchez-Daza, A., & Zurita-González, J. (2015). La crisis financiera internacional de 2008 y algunos de sus efectos económicos sobre México. Contaduría y Administración, 60(Supplement 2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cya.2015.09.011

Kalak, I. E., Azevedo, A., Hudson, R., & Karim, M. A. (2017). Stock liquidity and SMEs’ likelihood of bankruptcy: evidence from the US market. Research in International Business and Finance, 42(Supplement C), 1383–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.077

Kemme, D. M., & Koleyni, K. (2017). Exchange rate regimes and welfare losses from foreign crises: the impact of the US financial crisis on Mexico. Review of International Economics, 25(1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12259

KPMG. (2013). Empresas familiares en México: el desafío de crecer, madurar y permanecer. KPMG en México.

Lee, C.-C. (2013). Business service market share, international operation strategy and performance. Baltic Journal of Management, 8(4), 463–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-02-2013-0020

Ledur, L. , & Carvalho, F. (2006). Las empresas latinoamericanas: factores determinantes de su desempeño. En Gobernabilidad corporativa, responsabilidad social y estrategias empresariales en América Latina, CEPAL/Mayol Ediciones. Pp. 201-221.

Maquieira, C., Preve, L., & Sarria-Allende, V. (2012). Theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence and distinctive features in Latin America. Emerging Markets Review, 13(2), 118–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2011.11.001

McGowan, A., Andrews, D., & Millot, V. (2016). The Walking Dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries. OECD Economics Departament Working Papers. https://doi.org/10.1787/180d80ad-en

Miles, R., Snow, C., Meyer, A., & Coleman, H. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and process. The Academy of Management Review, 3(3), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/257544

Mojica, F. J. (2010). The future of the future: strategic foresight in Latin America. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(9), 1559–1565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.07.008

Moreno-Menéndez, A. M., Castiglioni, M., & Cobeña-Ruiz-Lopera, M. M. (2021). The influence of socio-emotional wealth on the speed of the export development process in family and non-family firms. European Journal of Family Business, 11(2), 10-25. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10782

Nakamura, J.-I., & Fukuda, S.-I. (2013). What happened to “zombie” firms in Japan?: Reexamination for the lost two decades. Global Journal of Economics, 02(02), 1350007. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2251361213500079

Peters, A. (2016). Monetary policy, exchange rate targeting and fear of floating in emerging market economies. International Economics and Economic Policy, 13(2), 255–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0300-0

Rahimi, J. (2016). The effect of business strategies on the relationship between leverage relative and financial performance of listed companies in Tehran Stock Exchange. Information and Knowledge Management, 6(2), 17–26.

Ramírez-Solís, E., Baños-Monroy, V., & Rodríguez-Aceves, L. (2016). Family business in Latin America: the case of Mexico. En The Routledge companion to family business (1.ª ed.). Routledge.

Rezazade, M., & Lashkarbolouki, M. (2016). Unlearning troubled business models: from realization to marginalization. Long Range Planning, 49(3), 298–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2015.12.005

Rienda, L., & Andreu, R. (2021). The role of family firms’ heterogeneity on the internationalisation and performance relationship. European Journal of Family Business, 11(2), 26-39. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10591

Rumelt, R. P., Schendel, D., & Teece, D. J. (1991). Strategic management and economics. Strategic Management Journal, 12(S2), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250121003

San-Jose, L., Urionabarrenetxea, S., & García-Merino, J. D. (2021). Zombie firms and corporate governance: what room for maneuver do companies have to avoid becoming zombies? Review of Managerial Science, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00462-z

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest and the business cycle. Harvard University Press.

Shapiro, C. (1989). The theory of business strategy. The RAND Journal of Economics, 20(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/2555656

Shaw, E. (2009). Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford University Press.

Shen, G., & Chen, B. (2017). Zombie firms and over-capacity in Chinese manufacturing. China Economic Review, 44, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.05.008

Silva, A., & Chavez, G. (2002). Components of execution costs: evidence of asymmetric information at the Mexican Stock Exchange. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 12(3), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1042-4431(02)00006-9

Simerly, R., & Li, M. (2000). Environmental dynamism, capital structure and performance: a theoretical integration and an empirical test. Strategic Management Journal, 21(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200001)21:1<31::AID-SMJ76>3.0.CO;2-T

Slater, S., Olson, E., & Finnegan, C. (2011). Business strategy, marketing organization culture, and performance. Marketing Letters, 22(3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-010-9122-1

Tan, Y., Huang, Y., & Woo, W. T. (2016). Zombie firms and the crowding-out of private investment in China. Asian Economic Papers, 15(3), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/ASEP_a_00474

Uchida, H., Miyakawa, D., Hosono, K., Ono, A., Uchino, T., & Uesugi, I. (2015). Financial shocks, bankruptcy, and natural selection. Japan and the World Economy, 36, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2015.11.002

Urionabarrenetxea, S., Garcia-Merino, J. D., San-Jose, L., & Retolaza, J. L. (2018). Living with zombie companies: do we know where the threat lies? European Management Journal, 36(3), 408-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.05.005

Urionabarrenetxea, S., San-Jose, L., & Retolaza, J.-L. (2016). Negative equity companies in Europe: theory and evidence. Business: Theory and Practice, 17(4), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.17.11125

Valdés, A., & Roldán, R. (2016). Dependencia condicional en colas entre el mercado accionario y el crecimiento económico: el caso mexicano. Investigación Económica, 75(296), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inveco.2016.07.005

Vidal, G., Marshall, W. C., & Correa, E. (2011). Differing effects of the global financial crisis: why Mexico has been harder hit than other large Latin American countries. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 30(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9856.2010.00501.x

Watkins, K. (2018). Financial performance in Mexican family vs. non-family firms. Contaduría y Administración, 63(2), 0-0. https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2018.1214

Watkins, F., & Flores, V. (2016). Determinants of firms’ ownership concentration in Mexico. Contaduría y Administración, 61(2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cya.2015.05.015