European Journal of Family Business (2021) 11, 40 -55

Family and Non-Family Businesses in Iran: Coupling among Innovation, Internationalization and Growth-Expectation

Mahsa Samsamia*, Thomas Schøttb

a University of Santiago de Compostela, La Coruña, Spain

b American University in Cairo, Egypt; University of Agder, Norway; University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Research paper. Received: 2020-10-15; accepted: 2021-09-01

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M1, O30

KEYWORDS

Coupling, Exporting, Family business, Growth-Expectations, Innovation, Iran

CÓDIGOS JEL

M1, O30

PALABRAS CLAVE

Acoplamiento, Empresa familiar, Expectativas de crecimiento, Exportaciones, Innovación, Irán

Abstract Gallo and Sveen, in 1991, problematized whether family businesses can implement factors facilitating internationalization. Focusing on innovation, export and growth-expectation in a family business, we consider how these three outcomes are aligned, with a coupling that may be loose or tight, a synergy that benefits the business. This raises a further issue, is governance of a business affecting not only each of the outcomes, but also their coupling? A representative sample of 530 businesses in Iran was surveyed in 2018 for Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Innovation, export and growth-expectation are found to be lower in family businesses. Coupling between innovation and export, and also between export and growth-expectation, are found to be looser in family businesses. Findings suggest that coupling among performance outcomes in family businesses can feasibly be tightened, thereby reinforcing performance. The findings contribute to ways of enhancing performance endeavors of family businesses with practical implications as advocated by Gallo and Sveen.

Empresas familiares y no-familiares en Irán: acoplamiento entre innovación, internacionalización y expectativas de crecimiento

Resumen Gallo y Sveen, en 1991, se plantearon si las empresas familiares podían implementar factores que facilitasen la internacionalización. Centrándonos en la innovación, las exportaciones y las expectativas de crecimiento en la empresa familiar, consideramos cómo estos tres factores se alinean, con un acoplamiento que puede ser débil o fuerte, una sinergia que beneficia al negocio. Esto plantea una cuestión adicional: ¿la gobernanza de una empresa puede no solo afectar a cada uno de los factores, sino también a su acoplamiento? Una muestra representativa de 530 empresas de Irán fue encuestada en 2018 para el Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Se demuestra que la innovación, las exportaciones y las expectativas de crecimiento son menores en las empresas familiares. El acoplamiento entre innovación y las exportaciones, y también entre las exportaciones y las expectativas de crecimiento, son más suaves en las empresas familiares. Los hallazgos sugieren que el acoplamiento entre los resultados en las empresas familiares pueden ser fortalecidos, reforzando así la rentabilidad. Los resultados contribuyen a mejorar la rentabilidad de las empresas familiares con implicaciones prácticas, como lo defienden Gallo y Sveen.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i2.10444

Copyright 2021: Mahsa Samsami, Thomas Schøtt

European Journal of Family Business is an open access journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial. ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

*Corresponding author

E-mail: samsami.mahsa@rai.usc.es

1. Introduction

Miguel Angel Gallo and Jannicke Sveen contributed a seminal manifesto, Internationalizing the Family Business: Facilitating and Restraining Factors (1991). They suggested that if a family business “is unable to take advantage of the factors that facilitate internationalization or overcome the factors that restrain it, the process will probably fail” (p. 181). With this suggestion, they identified a gap in our knowledge of family business and emphasized the importance of filling the gap. Moreover, they set an agenda for research on facilitating and restraining factors of internationalization of family business. A review of the three decades of research on family firms internationalization by Debellis and coworkers also points to the earliest article as that of Gallo and Sveen in 1991 (Debellis et al., 2021). Still, identifying factors facilitating and restraining internationalization remains a gap in family business research which continues to draw attention of researchers (Casillas & Moreno-Menéndez, 2017).

Standing on their shoulders, we here focus on a factor that expectedly facilitates internationalization of a family business. We hypothesize that internationalization will be facilitated by coupling internationalization with innovation and with the pursuit of growth of the business. Let us elaborate on the strategy of pursuing outcomes with a coupling.

If you watch the members of the board in a meeting in a family business, you witness that family considerations and traditions enter into a wide range of decisions. In a family firm, board members, the CEO, and even executive senior directors are usually members of the same family. Consequently, they will make decisions, strategies and goals, which appear to be different from those in non-family businesses (Soler et al., 2017). The family firm affects business through participation in the board of directors and management teams (Casillas & Moreno-Méndez, 2017). Bodolica et al. (2015) found that a specific strategy for managing family-business boundaries is able to retain an optimal governance configuration for securing its continued success. Moreover, the goals adopted by managers will affect performance. Shapiro et al. (2015) concluded that corporate governance affects innovation. Conversely, prominence of family members in managerial positions may constrain international entrepreneurship processes (Alayo et al., 2019; Boellis et al., 2016). Following this, Bauweraerts et al. (2019) found a negative effect of CEO on the export scope. This raises the question of whether family firms’ decisions work better. Martínez and colleagues (2007) found that public family firms perform better than public non-family firms according to evidence from public companies in Chile. According to Singh and Gaur’s study (2013) governance matters for innovation and internationalization strategies as performance outcomes of firms. However, family participation in governance may have a negative effect on innovation input and a positive influence on innovation output (Matzler et al., 2015). But the performance of a company is multi-dimensional, so it is important to consider how governance will affect performance outcomes, notably innovation, exports, and growth-expectations. We elaborate on this by adding a focus on coupling among outcomes.

Coupling between innovation and financing in a business is a capability (Wang & Schøtt, 2020). Coupling among performance outcomes can be an advantage in accord with Gallo and Sveen’s manifesto (1991). Coupling is of importance for facilitating and reinforcing internationalization. Thus, we pose a research question: what are the effects of family versus non-family governance upon innovation, internationalization, and growth-expectations? Specifically, what is the effect of governance upon coupling among outcomes?

This research question is here addressed by analyzing effects of family vs non-family governance and three-fold performance. We analyze effects of governance on performance outcomes, then coupling among outcomes, and then analyze how governance moderates coupling.

A major contribution of our study is an account of how coupling among outcomes differs between family businesses and non-family businesses. Specifically, a contribution is to show that coupling is loose within family businesses and tighter within non-family businesses, at least in our studied society, Iran. Our examination of coupling between internationalization and other performance outcomes thereby contributes to the research direction initiated by Gallo and Sveen (1991).

The following sections describe the theoretical perspective on family versus non-family governance and performance, develop hypotheses concerning effects of governance on performance, describe our research design, and report results. The conclusion elaborates our contribution to the agenda set by Gallo and Sveen (1991).

2. Theoretical Perspective on Family Governance and Performance

Family firms differ from non-family firms in some ways such as their objectives, corporate governance, and entrepreneurial behavior (Love & Roper, 2013), which can be caused by family traditions and orientation to different values (Kirsipuu, 2013). Family business in terms of ensuring its continuity over several generations is a sample of an arduous task in order to build a firm (Gallo, 2021). Moreover, goals are of importance in the prediction of firm performance (De Massis et al., 2018). Family firm goals comprise both family-centered and business-centered goals (Chrisman & Patel, 2012). Family goals and business-centered goals are financial such as financial gains or non-financial in nature like positive self-image and well-being (Binz et al., 2017; Dyer Jr & Whetten, 2006; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Family ownership interacts with the presence of non-economic goals to gain economic benefits and influence firm performance (Randolph et al., 2019). Firms may direct their innovation strategies to support long-term survival in support of dynastic succession intentions, rather than maximizing profits (Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). Family business goals are formed and outcomes are achieved through mechanisms (Basco & Calabrò, 2017; De Massis et al., 2018; Williams Jr et al., 2018).

Governance, and resources of family firms are the main determinants of outcomes, the continuation of family involvement, firm survival and renewal, and financial performance (Chrisman et al., 2013). Family control has an important impact on entry modes (Sestu & Majocchi, 2020). An increase in ownership concentration has a positive impact on innovation (Shapiro et al., 2015; Singh & Gaur, 2013). Family participation in governance has a negative effect on innovation input but a positive influence on innovation output (Matzler et al., 2015). The influence of family governance on performance is moderated by the nature of new products introduced (Cucculelli et al., 2016).

Family firms perform better (Basco, 2014; Martínez et al., 2007) when following a product differentiation strategy and balance their family and business-oriented decision-making (Basco, 2014). While non‐family firms develop rapidly to attract outside resources, family firm proprietors adopt a cautious approach to growth (Kotey, 2005). Non-family small- and medium- enterprises (SMEs) focus on broader network relationships, such as universities, public institutions, and fair trade organizations (Basco & Calabrò, 2016). As this brief review indicates, studies of the effect of governance on outcomes have mostly concluded that family businesses perform less well than non-family businesses, in terms of innovation, exporting, and profit, partly because family business are less focused on such outcomes.

What, then, is the coupling among performance outcomes? Both financing and innovation are important for a new venture to succeed and coupling between innovation and financing is a capability (Wang & Schøtt, 2020). Given Chou and colleagues’ study (2016), coupled open innovation is positively related to incremental performance outcomes but not with radical outcomes.

Family businesses play a critical role in the economic development as well as globalization efforts of their countries, which is of importance (Yildirim-Öktem, et al., 2018). The favorable ownership structure of a company reinforces the positive impact of research and development abilities on internationalization (Singh & Gaur, 2013). Family firm prevalence has a moderator positive impact on export performance (Carney et al., 2017), and also the presence of non-family and family businesses moderates the relationship between family ownership and internationalization strategy (Ray et al., 2018). Networking in the transnational sphere and in the sphere of business operations promotes outcomes such as innovation, exporting, and growth expectations. As this brief review indicates, performance outcomes tend to be loosely coupled, and rarely tightly coupled. Family businesses behave differently compared to non-family firms due to family traditions and orientation to different values. Non-family businesses focus on their financial performance, whereas family businesses focus both on financial performance and on creating socio-emotional well-being for the family. The lesser focus on financial performance in family businesses implies, theoretically, that family businesses have lower performance outcomes in terms of innovation, exporting and growth-expectations. The stronger focus on financial performance in non-family businesses also implies, theoretically, that coupling will be weaker in family businesses.

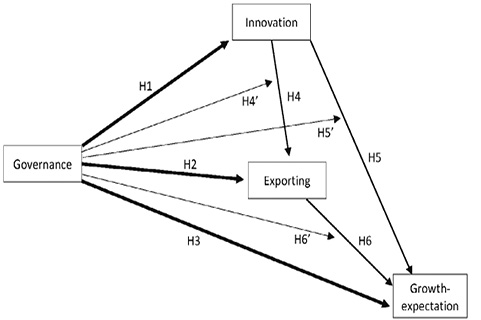

The theoretical perspective on governance and performance is three-fold. First, governance affects performance outcomes. These effects are the three thick arrows in Figure 1. Second, performance outcomes are coupled. Their coupling is the three medium thick arrows. Third, governance moderates coupling among outcomes. These moderating effects are the three thin arrows.

Figure 1. Hypothesized effects

The scheme indicates hypotheses to be developed in the next section.

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Family vs non-family governance affecting performance outcomes

3.1.1. Governance affecting innovation

Is governance affecting innovation, i.e., does innovation differ between family businesses and non-family businesses in Iran?

Theorizing around innovation in family business revolves around risk and uncertainty. Family businesses tend to be averse to risk and avoid uncertainty. But innovative work is inherently risky and uncertain. Therefore, theoretically, family businesses may avoid innovative work. Let us elaborate and consider the evidence before specifying the hypothesis. Innovation plays a significant role in family and non-family firms (Price et al., 2013). Family businesses differ from non-family ones in product innovation and the innovation process (De Massis et al., 2015). Family firms may be more innovative than non-family firms (Tolba et al., 2020) and (Llach & Nordqvist, 2010), have a higher propensity to invest in innovation (Classen et al., 2014), and benefit from innovative orientation (Lodh et al., 2014).

The distinctive strategic goals of the family firm are driven by the family’s willingness (De Massis et al., 2018). The family member as owner and manager results in a higher propensity towards initiatives (Boellis et al., 2016). The difference between family and non-family business in their innovation, in several other countries than Iran, leads us to specify our first hypothesis about businesses in Iran:

Hypothesis 1. Governance affects innovation, in that family businesses innovate less than non-family businesses.

3.1.2. Governance affecting exporting

Let us now consider a second performance outcome, namely exporting. Does governance affect exporting, i.e., is exporting higher or lower in family businesses than in non-family businesses in Iran?

In internationalization processes, family businesses behave differently from non-family businesses. Entering foreign markets and internationalization can be risky. Some businesses are averse to such risk-taking. We rely on the theorizing that family businesses are focused on conserving wealth for the family and therefore avoiding risk. During thirty years, the impact of family ownership, management, and governance on internationalization have been explored though at the 2014 declining stage, little research is known about the process of family firms’ internationalization and the role of the family in shaping this process (Debellis et al., 2021).

Family members’ values are related to their attitude to risk and international networks, (Casillas et al., 2017). In view of Lin’s result (2012), family ownership is of significant effectiveness in a firm’s internationalization processes. There is a negative relationship between internationalization and family ownership (Fernández & Nieto, 2006; Hanley et al., 2020). In internationalization, the ability of family businesses to make quick decisions is of importance (Kontinen & Ojala, 2010). It seems that family firms do not behave fundamentally differently from non-family firms in their internationalization (Arregle et al., 2017), yet they internationalize slower, and in the long-run more than non-family firms (Gallo & Estapé, 1992; Pukall & Calabrò, 2014). When family firms induce a regional strategy, their leaders are most beneficial (Banalieva & Eddleston, 2011).

Not only in the family firms but also in non-family businesses, there is a positive and significant tie between foreign investors’ ownership and the level of international sales (Calabrò et al., 2013). Families better internalize the long‐run benefits of internationalization (Minetti et al., 2015). They perform better than non-family businesses in trading (Rettab & Azzam, 2011). Exports are low for small family and non‐family firms (Kotey, 2005). The capabilities of management in family business lag behind those of their non-family counterparts as they expand internationally (Graves & Thomas, 2006), and are less likely to be internationally active (Thomas & Graves, 2005).

This brief review of theorizing and the mixed evidence leads us to specify a hypothesis about Iran:

Hypothesis 2. Governance affects exporting, in that family businesses export less than non-family businesses.

3.1.3 Governance affecting expectation for growth

Let us briefly consider a third outcome, namely the expectation for growth of the business. Does governance affect growth-expectation, so that expectation is higher or lower in family businesses than in non-family businesses in Iran?

Family and non-family firms react differently in acceptance of new technology, and in changing strategy. Family firms are risk-averse and behave traditionally. They may adopt new measures to a lesser extent than non-family firms. The family business is less likely to adopt modern management techniques (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007). In terms of economic development and growth, family businesses are of significance (Beck et al., 2009). Aguilera and coworker express the idea (2016) that given the more recent developments of capitalism in Asia, focused ownership structures along with families being large shareholders play an underlying role.

Family businesses on average have higher growth rates than non-family businesses (Miroshnychenko et al., 2021). Family firms appear to lack effective management (Bertrand & Schoar, 2006; Mehrotra et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2015).

Innovative orientation in the family business is both directly and indirectly associated with firm growth (Stenholm et al., 2016). Family firms establish form enduring ties with other family businesses to promote joint commercial interests and essentially growth (Breton-Miller et al., 2011; Salvato & Melin, 2008). Firms staying listed on the prime Standard perform well (Bessler et al., 2018). Non-family businesses manage to take new action more than family businesses. This brief review of studies leads us to suggest a further hypothesis concerning Iran:

Hypothesis 3. Governance affects growth-expectation, in that family businesses expect less growth than non-family businesses.

The above hypotheses are our baseline hypotheses. The hypotheses are not new, but they have not been tested in the case of Iran. More importantly, they are our starting point for developing new hypotheses.

3.2. Coupling of innovation and export differs between family and non-family businesses

The first issue about coupling is whether innovation and exporting are interrelated in a business. Innovation can make a contribution to a company for internationalization and will facilitate exporting. An innovative firm is trying to enter an emerging market due to increasing market share. There is a positive relationship between market orientation and innovation in a family firm (Beck et al., 2011), and a strong positive association between firm productivity and exports (Cassiman & Golovko, 2011). Product innovation rather than process innovation induces small non-exporting firms to enter the export market (Cassiman et al., 2010; Cassiman & Martinez-Ros, 2007; Love & Roper, 2013). Furthermore, process innovation independently has a positive impact on the decision to export (Añón & Driffield, 2011). While exporting status remarkably may increase the likelihood of introducing product innovations (Bratti & Felice, 2012; Vanyushyn et al., 2018), innovation persuades firms to improve and increase their export activities (Kunday & Şengüler, 2015; Monreal-Pérez et al., 2012). There is a strong positive link between exporting and productivity, which is largely moderated via (product) innovation (Cassiman et al., 2010; Love & Roper, 2013). There is a positive influence of first-generation family firms on the learning-by-exporting effect on product innovation (Sánchez-Marín et al., 2020). These studies of innovation and exporting support the proposition that innovation affects exporting, in that high innovation increases exporting. This proposition is depicted as an arrow in Figure 1 and is reconfirmed in our analysis below. This proposition is not new, but it here serves as our baseline or starting point for considering how the coupling is influenced by governance.

Some businesses prefer to capitalize on being global (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2007; Filbeck & Lee, 2000). Corporate governance plays a significant role in firms’ performance (Arregle et al., 2017; Minetti et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2018). Governance also affects internationalization (Kalhor & Ghalwash, 2020). Family ownership plays a significant role in productivity and the decision to export (Arregle et al., 2017; Minetti et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2018). Sánchez-Marín et al.’s findings in 2016 demonstrate that family businesses give rise to a greater orientation towards the clan culture, while non-family businesses show their preference in order to not only the market also but hierarchy cultures. Family commitment culture may operate against internationalization (Segaro et al., 2014).

There are important diversities among family and non-family SMEs in the matter of open innovation search strategies (Basco & Calabrò, 2016). Ray and coworkers (2018) demonstrated how the presence of non-family ownership and family business moderate the relationship between family ownership and internationalization strategy. High involvement of non-family members in governance structure affects positively family firms’ pace of the process of making something international so that this relationship is mediated through the international entrepreneurial orientation of the firm (Calabrò et al., 2017). These studies lead us to specify our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4. Governance moderates the effect of innovation on exporting, in that the effect of innovation on exporting is less in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

3.3. Coupling of innovation and growth-expectation differs between family and non-family businesses

Let us consider another coupling, namely the coupling between innovation and growth-expectation in Iran. When a firm is innovative, undoubtedly it will adopt new actions. Innovative companies try to develop with the contribution of new technologies. The more a company innovates, the more growth-expectation increases. Entrepreneurs who have innovation also have higher growth-expectations. Given experienced entrepreneurs usually is more careful concerning growth-expectations (Poblete, 2018). Radical innovations are able to be an association with sales growth (Forsman & Temel, 2011). Some high–technology firms pursue a high R&D investment strategy (Gomez–Mejia et al., 2014) and exhibit a higher internationalization propensity (Piva et al., 2013).

Growth motivations are the outcome of expected growth (Verheul & Van Mil, 2011). A firm’s innovation-related activities are able to drive its competitive performance (Liao & Rice, 2010). Family firms that are professionals are more effective and play a significant and positive role in firms’ ability (Clausen & Pohjola, 2013; Diéguez-Soto et al., 2016). This brief discussion of innovation affecting growth-expectation support the proposition that innovation affects growth-expectation, in that high innovation increases growth-expectation. This proposition is depicted as an arrow in Figure 1 and is reconfirmed in our analysis.

Coupling between innovation and growth-expectation may be influenced by governance. Family firms differ from non-family firms in some ways when it comes to being innovative and growth-expectation rates. Although family businesses may innovate more than non-family businesses, they do not adopt new action very well. So, it is likely that the effect of innovation on growth-expectation is less in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

This leads us to specify another hypothesis, about the effect of innovation on growth-expectation:

Hypothesis 5. Governance moderates the effect of innovation on growth-expectation, in that the effect of innovation on expectations is less in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

3.4. Coupling between innovation and growth-expectation differs between family and non-family businesses

Let us also consider yet another coupling, namely the coupling between exporting and growth-expectation in Iran. Family firms behave differently in comparison with non-family firms with regard to internationalisation and growth-expectation. Family businesses perform better than non-family businesses in internationalisation. On the other hand, they are less likely to adopt new action very well. It is likely that exporting increases growth-expectation in the family business albeit less than in non-family firms.

Kunday and colleague in 2015 expressed that policymakers tend to increase the internationalization of SMEs. There is a negative tie between necessity-driven entrepreneurship and both business growth and business growth-expectations, yet the positive relationship between opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and both business growth and business growth-expectation is observed (Zali et al., 2013). These studies support the proposition that exporting affects growth-expectation, in that high exporting increases growth-expectation. This proposition is depicted as an arrow in Figure 1 and is reconfirmed in our analysis below. This coupling may be influenced by governance. Kunday and colleague in (2015) reveal a moderating role of the motive of operation on the export orientation. In internationalization, one of the important points in family businesses is their ability to make quick decisions (Kontinen & Ojala, 2010).

Iranian entrepreneurs in the diaspora have larger networks, which have positive impacts on their innovativeness, exporting, and growth-expectation (Cheraghi & Yaghmaei, 2017). Locus of control, entrepreneurship education and some other factors tend to have significant consequences for the growth intentions (Neneh & Vanzyl, 2014). Following these studies, our hypothesis posits:

Hypothesis 6. Governance moderates the effect of exporting on growth-expectation, in that the effect of exporting on expectation is less in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

These hypotheses are tested in the following.

4. Research Design

The ideas concern family and non-family businesses. This ‘population’ is here studied within one country, Iran, which has a very traditional culture where life revolves around the family. We use data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, GEM (www.gemconsortium.orgwww.gemconsortium.org).

4.1. Sampling

GEM conducts an annual survey of the adult population, aiming at a national probability sample, in Iran more than 3,000 adults annually, with a core of questions that is the same from year to year and in all participating countries (www.gemconsortium.org; Bosma, 2013). The survey design is proposed by the national GEM team of researchers in the Faculty of Entrepreneurship at Tehran University. The design is reviewed, perhaps revised, and eventually approved by the data team of the global GEM consortium. The interviews are carried out by dozens of graduate students from the Faculty, mostly around their hometowns across the country, coded by the team of researchers, and submitted to the data team of the global consortium for checking quality and for harmonization and pooling with the survey data from the other countries around the world (Bosma, 2013). The pooled data are initially available to the members for analyses, and then made publicly and freely available on the website www.gemconsortium.org.

The questionnaire asks the sampled adults whether they own and manage a starting or operating business. In 2018, questions were added to identify family businesses and non-family business, as described below. Thereby a representative sample of 530 family and non-family businesses in Iran was obtained.

4.2. Measurements

The measures are well-established in two decades of GEM research (Bosma et al., 2013), except the questions identifying family business, which were added in 2018.

4.2.1 Family versus non-family governance

A respondent who reported to be owning and managing a starting or operating business was asked about ownership and management, (a) Will this business for the most part be owned by you and your family and relatives? And (b) Will this business mostly be managed by you and your family and relatives? A business that is mostly owned, and also mostly managed by the family, is a family business. A non-family business is thus a business that is not mostly owned or that is not mostly managed by the family. One-person businesses (with one owner-manager and no others) are excluded from our study.

4.2.2. Innovation

Innovation is measured by an index based on three questions asking about process-innovation, product-innovation, and competitiveness, (a) How long have the technologies or procedures used for this product or service been available? And (b) Will all, some, or none of your potential customers consider this product or service new and unfamiliar? And (c) Right now, are there many, few, or no other businesses offering the same products or services to your potential customers? Each question was answered on a three-point Likert scale. The three measurements are positively correlated, so they are averaged into an index of innovation. This index is used in numerous studies (e.g., Ashourizadeh, 2017; Schøtt & Jensen, 2016; Schøtt & Sedaghat, 2014).

4.2.3. Exporting

Exporting is measured as the percentage of sales that are to customers abroad, What percentage of your annual sales revenues will usually come from customers living outside your country? The percentage is logged to reduce skewness of the distribution. This measure is used in numerous studies (e.g., Ashourizadeh, 2017; Bosma, 2013).

4.2.4. Growth-expectation

The owner-manager was asked how many persons work for the business at present and how many are expected to work for the business five years later. (a) How many people are currently working for this business? And (b) How many people, including both present and future employees, will be working for this business five years from now? The expectation for change is then measured as Log (persons expected in five years) – Log (persons at present), where we have taken logarithms to reduce the skew. This measure of growth-expectation is used in numerous studies (e.g., Ashourizadeh, 2017).

4.2.5. Control variables

The GEM survey enables us to control for several characteristics, which are related to innovation, export and growth-expectation (Bosma et al., 2013). The control variables are included; (a) Motive for the business as either opportunity (coded 1) or necessity (coded 0); responding to the question, Are you involved in this start-up to take advantage of a business opportunity or because you have no better choices for work? (b) Age of the business, coded in year, and logged to reduce skew; (c) Owners, as the count of owners, logged; (d) Size of the business, as persons working for the business at present, as quoted above, logged; (e) Sector, with four categories, the extractive sector, the transformative sector, the business service sector, and the consumer service sector; (f) Gender, coded 0 for women and 1 for men; (g) Age of the entrepreneur, coded in years; and (h) Education, as years to highest completed degree.

4.3. Techniques for data analysis

Background of the family and non-family businesses are described by the frequencies and averages of the organizational characteristics (Table 1).

Differences between family and non-family businesses in outcomes are ascertained by averages of innovation, export and growth-expectation, and each difference is tested by a t-test (Table 2).

The hypotheses are tested, with controls, in multiple regressions. We use linear regressions because the dependent variables are all numerical. The hypothesis about an effect of family vs non-family governance directly upon an outcome is tested by a regression coefficient with a t-test of its significance (Table 3, Models A, B, C, D, G, H).

Coupling between two outcomes is ascertained in a multiple linear regression where one outcome is dependent variable and the other outcome is an independent variable; their coupling is then indicated by the regression coefficient with a t-test of its significance (Table 3, Models D, H).

A hypothesis about an effect of family vs non-family governance upon coupling of one outcome with another outcome is tested in a linear regression of one outcome upon governance and the other outcome and including their interaction term, the product of governance and the former outcome. How family vs non-family governance moderates the coupling is then ascertained as the interaction effect, indicated by the regression coefficient of the interaction term, with a t-test of its significance (Table 3, Models E, F, I, J, K).

5. Results

5.1. Background of the businesses

Background of family and non-family businesses is seen in the frequencies and averages of their characteristics, Table 1.

Table 1. Averages and percentages in the sample

|

All |

Family |

Non-family |

||

|

Sample |

N businesses |

530 |

360 |

170 |

|

Governance: family |

Percentage |

68% |

||

|

Motive: opportunity |

Percentage |

55% |

56% |

53% |

|

Age of business |

Mean years |

7.8 |

8.2 |

6.4 |

|

Median years |

5 |

7 |

2 |

|

|

Owners of business |

Mean owners |

1.8 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

|

Median owners |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Size of business |

Mean persons |

9.4 |

9.4 |

9.3 |

|

Median persons |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Sector: extractive |

Percentage |

7% |

8% |

6% |

|

Sector: transforming |

Percentage |

25% |

26% |

23% |

|

Sector: business services |

Percentage |

18% |

16% |

23% |

|

Sector: consumer oriented |

Percentage |

50% |

50% |

48% |

|

Gender of owner-manager |

Percent males |

76% |

77% |

75% |

|

Age of owner-manager |

Mean years |

38.8 |

40.4 |

35.3 |

|

Education |

Mean years |

15.9 |

15.2 |

17.5 |

Table 2. Performance outcomes, by governance

|

Innovation |

Exporting |

Growth-expectation |

||||

|

Family businesses |

Non-family businesses |

Family businesses |

Non-family businesses |

Family businesses |

Non-family businesses |

|

|

High performance |

15% |

26% |

3% |

7% |

53% |

71% |

|

Medium performance |

24% |

24% |

18% |

23% |

33% |

19% |

|

Low performance |

61% |

50% |

79% |

70% |

14% |

10% |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

Mean |

1.21 *** |

1.32 |

1.66 ** |

3.41 |

0.44 *** |

1.02 |

|

N |

358 |

170 |

350 |

165 |

237 |

118 |

+ p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 (one-sided t-test of difference)

Family businesses are seen in Table 1 to be older than non-family businesses, and their owner-managers likewise, which is typical. According to Table 1, it seems that the business age of family firms is higher than non-family companies. In addition, the age of family business owners is slightly lower than non-family companies, but this is not much different. The size of family businesses is almost the same as non-family businesses, which is related to the number of manpower and owners. The level of knowledge (higher education) of the responding owner-managers of non-family companies is higher than that of family companies. Differences between family and non-family businesses in outcomes are seen in averages, Table 2.

Results demonstrate that governance is related to performance outcomes; innovation, exporting and growth-expectations. That is, performance outcomes differ between family businesses and non-family businesses in Iran. Specifically, family businesses are innovating less than non-family businesses, Table 2. This lends some support for H1 when no other conditions are controlled for. Family businesses are exporting less than non-family businesses, Table 2. This supports H2 when no other conditions are controlled for. Family businesses have lower growth-expectations than non-family businesses, Table 2. This supports H3 when no other conditions are controlled for. We shall see that these relationship between governance and performance largely vanish when other conditions are controlled for, in the next section.

5.2. Effects of governance upon performance

Our hypotheses are all about effects of family vs non-family governance upon performance, specifically innovation, export, and growth-expectation. The effects are ascertained by multiple linear regression, Table 3, controlling for other conditions.

Table 3. Innovation, exporting and growth-expectation affected by governance

|

Innovation |

Export |

Growth-expectations |

|||||||||

|

Main effects only |

Main effects only |

Main effects only |

Main effects only |

Inter-actions |

Inter-actions |

Main effects only |

Main effects only |

Inter-actions |

Inter-actions |

Inter-actions |

|

|

Model A |

Model B |

Model C |

Model D |

Model E |

Model F |

Model G |

Model H |

Model I |

Model J |

Model K |

|

|

Governance: Family |

-0.10 *** H1 |

-0.03 |

-0.23 ** H2 |

-0.05 |

0.58 |

0.47 |

-0.57 *** H3 |

-0.15 |

-0.08 |

-0.26 |

-0.18 |

|

Innovation |

0.30 * |

0.94 *** |

0.56 * |

0.93 *** |

1.46 *** |

0.87 *** |

|||||

|

Export |

0.11 * |

0.51 *** |

0.17 * |

||||||||

|

Governance x Innovation |

-0.60 ** H4 |

-0.41† |

-0.26 H5 |

0.07 |

|||||||

|

Governance x Export |

-0.31 * H6 |

-0.09 |

|||||||||

|

Age of business |

0.00 |

-0.03 |

-0.03 |

-0.39 *** |

-0.39 *** |

||||||

|

Owners |

0.11 ** |

0.26 ** |

0.25 ** |

0.16 |

0.15 |

||||||

|

Size of business |

0.00 |

-0.08 † |

-0.08 † |

-0.39 *** |

-0.39 *** |

||||||

|

Sector: extracting |

0.04 |

-0.54 ** |

-0.53 *** |

0.02 |

0.01 |

||||||

|

Sector: transforming |

0.08 † |

-0.16 |

-0.15 |

0.24 † |

0.23 † |

||||||

|

Sector: business services |

0.10 * |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.24 † |

0.24 † |

||||||

|

Gender: male |

-0.10 * |

-0.23 * |

-0.26 * |

-0.07 |

-0.07 |

||||||

|

Age of owner-manager |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

||||||

|

Education |

0.01 * |

0.02 * |

0.02 * |

0.02 |

0.02 † |

||||||

|

Intercept |

1.32 *** |

1.14 *** |

0.64 *** |

-0.03 |

-0.58 * |

-0.38 |

1.05 *** |

0.20 |

0.95 * |

0.62 *** |

0.23 |

|

N businesses |

528 |

405 |

515 |

396 |

515 |

396 |

355 |

331 |

354 |

348 |

331 |

Linear regression with metric coefficients.

For sector, the consumer-oriented sector is the reference that each other sector is compared to.

† p < .10 * p<.05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001

Hypothesis 1 states that governance affects innovation, in that family businesses innovate less than non-family businesses. This hypothesis is tested in the regression in Model A, in Table 3. The effect is significant and negative as hypothesized (β = - 0.14; p = 0.001). This supports Hypothesis 1, when no other conditions are controlled. Interestingly, when holding other conditions constant, in Model B, the effect of governance on innovation seems to vanish. That is, innovation is lower in family businesses than in non-family businesses, but this is not because of the governance itself, but rather because of some other conditions such as gender, education, and age of the head of the business, which promote innovation in non-family businesses more than in family businesses.

Hypothesis 2 holds that governance affects exporting, in that family businesses export less than non-family businesses. This hypothesis is tested in Model C in Table 3. The effect is significant and negative as hypothesized (β = - 0.12; p = 0.004). This supports Hypothesis 2. Interestingly, when holding other conditions constant, in Model D, the effect of governance on export seems to vanish. That is, export is lower in family businesses than in non-family businesses, but this is not because of the governance itself, but rather because of some other conditions such as gender, education, and age of the head of the business, which promote export in non-family businesses more than in family businesses.

Hypothesis 3 posits that governance affects growth-expectation, in that family businesses expect less growth than non-family businesses. This hypothesis is tested in Model G. The effect is significant and negative as hypothesized (β = - 0.20; p ≤ 0. 0001). This supports Hypothesis 3. Interestingly, when holding other conditions constant, in Model H, the effect of governance on expectation largely vanishes. That is, expectation is lower in family businesses than in non-family businesses, but this is not because of the governance itself, but rather because of some other conditions such as gender, education, and age of the head of the business, which promote expectation in non-family businesses more than in family businesses.

The analysis reconfirms that innovation and exporting are coupled in that innovation promotes exporting. This is reconfirmed in Model D, where the coefficient is positive, reconfirming the proposition. Hypothesis 4 is taking this one step further by claiming that the coupling between innovation and exporting is moderated by governance, in that the effect is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses. This interaction is tested in model E. The interaction effect is negative, i.e., the effect of innovation on exporting is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses, supporting H4 (β = - 0.40; p = 0.006).

The proposition that innovation and growth-expectations are coupled in that innovation promotes expectations is tested in Model H. The coefficient is positive, reconfirming the proposition. Hypothesis 5 takes this one step further by claiming that the coupling between innovation and growth-expectation is moderated by governance, in that the effect is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses. This interaction is tested in model I. The interaction effect is insignificant (p = 0.23), i.e., the evidence gives no support for our H5.

The proposition that exporting and growth-expectations are coupled in that exporting promotes expectations is tested in Model H. The coefficient is positive, supporting the proposition. Hypothesis 6 takes this one step further by claiming that the coupling between exporting and growth-expectation is moderated by governance, in that the effect is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses. This interaction is tested in model J. The interaction effect is significant and negative as hypothesized (β = - 0.19; p = 0.012). This supports H6. The above findings are discussed in the concluding section, below.

6. Discussion

Gallo and Sveen contributed their seminal manifesto, Internationalizing the family business: Facilitating and restraining factors, in 1991. Accordingly, our analyses of family and non-family businesses in Iran, addressed the question, what are the effects of governance upon innovation, internationalization, and growth-expectations? Specifically, what is the effect of governance upon coupling among outcomes? Here we consider our findings in relation to the literature, specify how the findings make a contribution to theorizing, point to their practical relevance, admit limitations, and suggest future research.

6.1. Findings

Our findings show that governance affects innovation and family businesses are innovating less than non-family businesses when no other conditions are controlled for, which is in agreement with studies by Llach and coworker (2010) and De Massis and colleagues (2015). Additionally, this differs from some previous studies (Basco & Calabrò, 2016; Classen et al., 2014). So when controlling for other conditions, there will be near-zero and insignificant coefficient for effect of governance upon exporting and it is in line with Basco and coworker’s studies (2016) and Classen and colleagues’ research (2014).

Our results are in accord with studies indicating that governance has impacts on exporting, in that family businesses are exporting less than non-family businesses, when no other conditions are controlled for (Gallo & Estapé, 1992; Graves & Thomas, 2006; Rettab & Azzam, 2011). Our result illustrates that governance has influences on growth-expectation, in that family businesses have lower growth-expectations than non-family businesses, and it matches those found by Bloom and coworker’s study (2007). Interestingly, expectations are not lower in family businesses when other conditions are controlled for.

As Kunday and Şengüler in (2015) and Monreal-Pérez and colleagues in (2012) found, innovation induces firms to improve and increase their export activities. Our findings are similar, innovation and exporting are coupled in that innovation promotes exporting. Our result are consistent with results obtained in Kalhor and Ghalwash’s study (2020) since our finding express that the coupling between innovation and exporting is moderated by governance, in that the effect or coupling is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses. Importantly, the interaction effect is negative, that is, the effect of innovation on exporting is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses, as some previous research illustrated (Arregle et al., 2017; Minetti et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2018). That is, the coupling between innovation and exporting is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

When our study finds innovation and growth-expectations are coupled in that innovation promotes expectations, it is consistent with other research like Forsman and Temel’s research (2011). We had hypothesized that family business governance would also weaken the coupling between innovation and growth-expectation. However, we do not discern any significant moderating effect of governance.

As put forward by Kunday and colleague in (2015), the evidence we found that exporting and growth-expectations are coupled in that exporting promotes expectations. Our research found that the coupling between exporting and growth-expectation is moderated by governance, in that the effect is weaker in family businesses than in non-family businesses.

6.2. Contribution

The broad field of management is split into numerous specializations. Even the study of performance is split into specializations, namely according to performance outcome. Innovation as a performance outcome is the focus of a research stream. Internationalization is the focus of another research stream. Growth of businesses is the focus of yet another research stream. This split also pervades research on family business, in that one focus is innovation in family business, another focus is internationalization of family businesses, and yet another focus is growth of family businesses.

A contribution here is to bring these foci together. We bring them together under the concept of coupling, a concept well established in organizational studies, for understanding the relations among components of an organization (Weick, 1976). Coupling has a structure and variation; it is tight in some organization and loose in other organizations. Coupling has antecedents, in that coupling is loose in some kinds of organizations, notably in public organizations, and tight in some other kinds of organizations, notably in commercial enterprises. Coupling has consequences, in that tight coupling is a capability that presumably promotes efficiency (Wang & Schøtt, 2020).

Our contribution to family business studies is two-fold. The first contribution is showing that family businesses and non-family businesses differ in performance, in that family businesses tend to perform less well than non-family businesses, not just on one outcome but across all three performance outcomes, when no other conditions are controlled for. However, the differences largely vanish when other conditions are held constant. The second contribution is showing that family businesses and non-family businesses differ in coupling among performance outcomes, in that coupling tends to be loose within family businesses and tighter within non-family businesses, at least in our studied society, Iran. Iran is a traditional society where people behave differently from secular societies and even other traditional societies in the world due to their culture. In traditional societies, gender, respect for parents, respect for elders, trust in family and close friends are important. Research results according to the data collected in Iran make a substantial contribution to coupling among performance outcomes among family and non-family businesses, which is loose and tighter, respectively.

Our findings demonstrate that coupling among performance outcomes facilitates internationalization, particularly in Iran on the ground that exporting in Iran is of more importance due to more different disruption like foreign sanctions compared to other countries. This coupling is an advantage in order to reinforce internationalisation. This advantage occurs in family business less frequently than in non-family businesses and ought to be reinforced, as Gallo and Sveen advocated (1991).

6.3. Relevance for practice and policy

These findings have significant implications for understanding how decisions, different policies, and governance in family businesses promote their performance.

Given the family roles in family firms, the members of the board need to make different policies and strategies to control threats, and obtain and grab efficient opportunities, so that this weakness becomes a strength. Coupling among performance outcomes entails mutual support and reinforcement among the outcomes and thereby promotes efficiency. Therefore, it will be advantageous for practice and policy to promote coupling. The gain may be especially high in family businesses where the coupling tends to be looser than in non-family businesses.

6.4. Limitations

The most important limitation lies in the fact that family firms are studied in only one country, a limitation shared with by far most studies of family business. An issue that was not addressed in this study was whether results are likely to differ between secular-rational and traditional societies. Family and non-family businesses in Iran as a traditional society in Middle East need to be compared with a secular-rational country.

6.5. Further research

It would be interesting to assess the effects of governance upon innovation, internationalization, and growth-expectations among family business and non-family firms in different countries in respect to secular-rational and traditional societies at least in the Arab world contrasted to other traditional societies and to secular-rational societies.

We suggested that the association of these factors is investigated in future studies in the different industries among family and non-family businesses. Governance policies in different industries can be effective and of significance among family firms and non-family businesses. For instance, family and non-family businesses in financial markets due to being high risk and the high speed of decision behave differently.

Focusing specifically on performance outcomes, it is interesting to contextualize the gaps found in this study, i.e., examine whether they are typical for the societies in the Middle East, are typical for emerging economies, or are typical for the world, or, conversely, are dependent on type of society and its institutions.

Focusing even more specifically on coupling, it is interesting to contextualize coupling, i.e., to examine whether coupling is related to not only family governance but also to type of society.

To assess the effects of governance upon performance outcomes, the association of these factors in the different industries among family/non-family businesses at the global level are underlying factors in future research as factors that are able to facilitate internationalization or overcome the factors that restrain it to progress successfully, as was suggested Gallo and Sveen (1991).

References

Aguilera, R. V., & Crespi-Cladera, R. (2016). Global corporate governance: on the relevance of firms’ ownership structure. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2015.10.003

Alayo, M., Maseda, A., Iturralde, T., & Arzubiaga, U. (2019). Internationalization and entrepreneurial orientation of family SMEs: the influence of the family character. International Business Review, 28(1), 48-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.06.003

Añón, D., & Driffield, N. (2011). Exporting and innovation performance: analysis of the annual small business survey in the UK. International Small Business Journal, 29(1), 4-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610369742

Arregle, J. L., Duran, P., Hitt, M. A., & van Essen, M. (2017). Why is family firms’ internationalization unique? A meta–analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(5), 801-831. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12246

Ashourizadeh, S. (2017). Iranian entrepreneurs at home and in diaspora: entrepreneurial competencies, exporting, innovation and growth-expectations. In: Rezaei, S., Dana, L. P., Ramadani, V. (eds). Iranian Entrepreneurship (pp. 249-262), Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50639-5_14

Banalieva, E. R., & Eddleston, K. A. (2011). Home-region focus and performance of family firms: the role of family vs non-family leaders. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(8), 1060-1072. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.28

Basco, R. (2014). Exploring the influence of the family upon firm performance: does strategic behaviour matter? International Small Business Journal, 32(8), 967-995. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613484946

Basco, R., & Calabrò, A. (2016). Open innovation search strategies in family and non-family SMEs: evidence from a natural resource-based cluster in Chile. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 29(3), 279-302. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-07-2015-0188

Basco, R., & Calabrò, A. (2017). “Whom do I want to be the next CEO?” Desirable successor attributes in family firms. Journal of Business Economics, 87(4), 487-509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-016-0828-2

Bauweraerts, J., Sciascia, S., Naldi, L., & Mazzola, P. (2019). Family CEO and board service: turning the tide for export scope in family SMEs. International Business Review, 28(5), 101583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.05.003

Beck, L., Janssens, W., Debruyne, M., & Lommelen, T. (2011). A study of the relationships between generation, market orientation, and innovation in family firms. Family Business Review, 24(3), 252-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511409210

Beck, L., Janssens, W., Lommelen, T., & Sluismans, R. (2009). Research on innovation capacity antecedents: distinguishing between family and non-family businesses. Paper presented at the EIASM Workshop on Family Firms Management Research.

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2006). The role of family in family firms. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 73-96. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-12-2019-0081

Bessler, W., Beyenbach, J., Rapp, M. S., & Vendrasco, M. (2018). The effects of the financial crisis on delisting decisions: evidence from family and non-family firms in Germany. Available at SSRN 3288654.

Binz, C. A., Ferguson, K. E., Pieper, T. M., & Astrachan, J. H. (2017). Family business goals, corporate citizenship behaviour and firm performance: disentangling the connections. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 16(1-2), 34-56. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMED.2017.082549

Bloom, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), 1351-1408. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2007.122.4.1351

Bodolica, V., Spraggon, M., & Zaidi, S. (2015). Boundary management strategies for governing family firms: a UAE-based case study. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 684-693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.08.003

Boellis, A., Mariotti, S., Minichilli, A., & Piscitello, L. (2016). Family involvement and firms’ establishment mode choice in foreign markets. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(8), 929-950. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2016.23

Bosma, N. (2013). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) and its impact on entrepreneurship research. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 143-248.

Bosma, N., Wennekers, S., Guerrero, M., Amoros, J. E., Martiarena, A., & Singe, S. (2013). Special report on entrepreneurial employee activity. London: GEM Consortium.

Bratti, M., & Felice, G. (2012). Are exporters more likely to introduce product innovations? The World Economy, 35(11), 1559-1598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2012.01453.x

Breton-Miller, I. L., Miller, D., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organization Science, 22(3), 704-721. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0541

Calabrò, A., Campopiano, G., Basco, R., & Pukall, T. (2017). Governance structure and internationalization of family-controlled firms: The mediating role of international entrepreneurial orientation. European Management Journal, 35(2), 238-248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016-/j.emj.2016.04.007

Calabrò, A., Torchia, M., Pukall, T., & Mussolino, D. (2013). The influence of ownership structure and board strategic involvement on international sales: the moderating effect of family involvement. International Business Review, 22(3), 509-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.07.002

Carney, M., Duran, P., van Essen, M., & Shapiro, D. (2017). Family firms, internationalization, and national competitiveness: Does family firm prevalence matter? Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(3), 123-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.06.001

Casillas, J. C., & Moreno-Menéndez, A. M. (2017). International business & family business: potential dialogue between disciplines. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejfb.2017.08.001

Cassiman, B., & Golovko, E. (2011). Innovation and internationalization through exports. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(1), 56-75. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.36

Cassiman, B., Golovko, E., & Martínez-Ros, E. (2010). Innovation, exports and productivity. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 28(4), 372-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2010.03.005

Cassiman, B., & Martinez-Ros, E. (2007). Product innovation and exports. Evidence from Spanish manufacturing, IESE Business School, Barcelona (pp. 1-36).

Cheraghi, M., & Yaghmaei, E. (2017). Networks around Iranian entrepreneurs at home and in diaspora: effects on performance. In Rezaei, S., Dana, L.-P., & Ramadani, V. (Eds.): Iranian Entrepreneurship: Deciphering the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Iran and in the Iranian Diaspora (pp. 263-275). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Chou, C., Yang, K.-P., & Chiu, Y.-J. (2016). Coupled open innovation and innovation performance outcomes: roles of absorptive capacity. 交大管理學報, 36(1), 37-68.

Chrisman, J. J., & Patel, P. C. (2012). Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 976-997. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0211

Chrisman, J. J., Sharma, P., Steier, L. P., & Chua, J. H. (2013). The influence of family goals, governance, and resources on firm outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1249-1261. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12064

Classen, N., Carree, M., Van Gils, A., & Peters, B. (2014). Innovation in family and non-family SMEs: an exploratory analysis. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 595-609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9490-z

Clausen, T. H., & Pohjola, M. (2013). Persistence of product innovation: comparing breakthrough and incremental product innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 25(4), 369-385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2013.774344

Cucculelli, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Product innovation, firm renewal and family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 90-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.02.001

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Majocchi, A., & Piscitello, L. (2018). Family firms in the global economy: Toward a deeper understanding of internationalization determinants, processes, and outcomes. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1199

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Pizzurno, E., & Cassia, L. (2015). Product innovation in family versus nonfamily firms: an exploratory analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12068

De Massis, A., Kotlar, J., Mazzola, P., Minola, T., & Sciascia, S. (2018). Conflicting selves: family owners’ multiple goals and self-control agency problems in private firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(3), 362-389. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12257

Debellis, F., Rondi, E., Plakoyiannaki, E., & De Massis, A. (2021). Riding the waves of family firm internationalization: a systematic literature review, integrative framework, and research agenda. Journal of World Business, 56(1), 101144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101144

Diéguez-Soto, J., Duréndez, A., García-Pérez-de-Lema, D., & Ruiz-Palomo, D. (2016). Technological, management, and persistent innovation in small and medium family firms: the influence of professionalism. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 33(4), 332-346. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1404

Dyer Jr, W. G., & Whetten, D. A. (2006). Family firms and social responsibility: preliminary evidence from the S&P 500. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(6), 785-802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00151.x

Fernández, Z., & Nieto, M. J. (2006). Impact of ownership on the international involvement of SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(3), 340-351. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400196

Filbeck, G., & Lee, S. (2000). Financial management techniques in family businesses. Family Business Review, 13(3), 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00201.x

Forsman, H., & Temel, S. (2011). Innovation and business performance in small enterprises: an enterprise-level analysis. International Journal of Innovation Management, 15(03), 641-665. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1363919611003258

Gallo, M. A. (2021). Coexistence, unity, professionalism and prudence. European Journal of Family Business, 11(1), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v11i1.11973

Gallo, M. A., & Estapé, M. J. (1992). The internationalization of the family business. Research paper No. 230, IESE Business School, University of Navarra, Spain.

Gallo, M. A., & Sveen, J. (1991). Internationalizing the family business: facilitating and restraining factors. Family Business Review, 4(2), 181-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1991.00181.x

Gallo, M. Á., Tàpies, J., & Cappuyns, K. (2004). Comparison of family and nonfamily business: financial logic and personal preferences. Family Business Review, 17(4), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00020.x

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 653-707. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gómez–Mejia, L. R., Campbell, J. T., Martin, G., Hoskisson, R. E., Makri, M., & Sirmon, D. G. (2014). Socioemotional wealth as a mixed gamble: revisiting family firm R&D investments with the behavioral agency model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(6), 1351-1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12083

Graves, C., & Thomas, J. (2006). Internationalization of Australian family businesses: a managerial capabilities perspective. Family Business Review, 19(3), 207-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00066.x

Hanley, A., Monreal-Pérez, J., & Sánchez Marín, G. (2020). Abandoning family management: analysis of the effects on exports. European Journal of Family Business, 10(2), 61-68. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i2.10099

Kalhor, E., & Ghalwash, S. (2020). Innovation mediating and moderating internationalization in family and non-family businesses: embeddedness in Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco and Turkey. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management, 38(2), 91-111.

Kirsipuu, M. (2013). Family and non-family business differences in Estonia. Discussions on Estonian Economic Policy: Topical Issues of Economic Policy in the European Union (2).

Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (2010). The internationalization of family businesses: a review of extant research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(2), 97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2010.04.001

Kotey, B. (2005). Goals, management practices, and performance of family SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510580816

Kunday, Ö., & Şengüler, E. P. (2015). A study on factors affecting the internationalization process of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 972-981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.363

Levie, J. (2010). The IIIP innovation confidence indexes 2009 report. Hunter Center for Entrepreneurship, University of Strathclyde.

Liao, T.-S., & Rice, J. (2010). Innovation investments, market engagement and financial performance: a study among Australian manufacturing SMEs. Research Policy, 39(1), 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.11.002

Lin, W.-T. (2012). Family ownership and internationalization processes: internationalization pace, internationalization scope, and internationalization rhythm. European Management Journal, 30(1), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.10.003

Llach, J., & Nordqvist, M. (2010). Innovation in family and non-family businesses: A resource perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 2(3-4), 381-399.

Lodh, S., Nandy, M., & Chen, J. (2014). Innovation and family ownership: empirical evidence from India. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 22(1), 4-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12034

Love, J., & Roper, S. (2013). SME innovation, exporting and growth. Enterprise Research Centre, White Paper (5).

Martínez, J. I., Stöhr, B. S., & Quiroga, B. F. (2007). Family ownership and firm performance: evidence from public companies in Chile. Family Business Review, 20(2), 83-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00087.x

Matzler, K., Veider, V., Hautz, J., & Stadler, C. (2015). The impact of family ownership, management, and governance on innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 319-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12202

Mehrotra, V., Morck, R., Shim, J., & Wiwattanakantang, Y. (2013). Adoptive expectations: rising sons in Japanese family firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.01.011

Miller, D., Xu, X., & Mehrotra, V. (2015). When is human capital a valuable resource? The performance effects of Ivy League selection among celebrated CEOs. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 930-944. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2251

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Zhu, S. C. (2015). Family firms, corporate governance and export. Economica, 82(s1), 1177-1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12156

Miroshnychenko, I., De Massis, A., Miller, D., & Barontini, R. (2021). Family business growth around the world. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(4), 682-708. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720913028

Monreal-Pérez, J., Aragón-Sánchez, A., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2012). A longitudinal study of the relationship between export activity and innovation in the Spanish firm: the moderating role of productivity. International Business Review, 21(5), 862-877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.09.010

Neneh, B. N., & Vanzyl, J. (2014). Growth intention and its impact on business growth amongst SMEs in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 172.

Piva, E., Rossi-Lamastra, C., & De Massis, A. (2013). Family firms and internationalization: an exploratory study on high-tech entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 108-129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-012-0100-y

Poblete, C. (2018). Growth expectations through innovative entrepreneurship: the role of subjective values and duration of entrepreneurial experience. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(1), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-03-2017-0083

Price, D. P., Stoica, M., & Boncella, R. J. (2013). The relationship between innovation, knowledge, and performance in family and non-family firms: an analysis of SMEs. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-5372-2-14

Pukall, T. J., & Calabrò, A. (2014). The internationalization of family firms: a critical review and integrative model. Family Business Review, 27(2), 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486513491423

Randolph, R. V., Alexander, B. N., Debicki, B. J., & Zajkowski, R. (2019). Untangling non-economic objectives in family & non-family SMEs: a goal systems approach. Journal of Business Research, 98, 317-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.017

Ray, S., Mondal, A., & Ramachandran, K. (2018). How does family involvement affect a firm’s internationalization? An investigation of Indian family firms. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 73-105. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1196

Rettab, B., & Azzam, A. (2011). Performance of family and non-family firms with self-selection: evidence from Dubai. Modern Economy, 2(04), 625-632. https://doi.org/10.4236/me.2011.24070

Salvato, C., & Melin, L. (2008). Creating value across generations in family-controlled businesses: the role of family social capital. Family Business Review, 21(3), 259-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865080210030107

Sánchez-Marín, G., Carrasco-Hernández, A. J., Danvila del Valle, I., & Sastre-Castillo, M. A. (2016). Organizational culture and family business: a configurational approach. European Journal of Family Business, 6(2), 99-107. https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v6i2.5022

Sánchez-Marín, G., Pemartín, M., & Monreal-Pérez, J. (2020). The influence of family involvement and generational stage on learning-by-exporting among family firms. Review of Managerial Science, 14(1), 311-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00350-7

Schøtt, T., & Jensen, K. W. (2016). Firms’ innovation benefiting from networking and institutional support: a global analysis of national and firm effects. Research Policy, 45(6), 1233-1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.03.006

Schøtt, T., & Sedaghat, M. (2014). Innovation embedded in entrepreneurs’ networks and national educational systems. Small Business Economics, 43(2), 463-476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9546-8

Segaro, E. L., Larimo, J., & Jones, M. V. (2014). Internationalisation of family small and medium sized enterprises: the role of stewardship orientation, family commitment culture and top management team. International Business Review, 23(2), 381-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.06.004

Sestu, M. C., & Majocchi, A. (2020). Family firms and the choice between wholly owned subsidiaries and joint ventures: a transaction costs perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(2), 211-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718797925

Shapiro, D., Tang, Y., Wang, M., & Zhang, W. (2015). The effects of corporate governance and ownership on the innovation performance of Chinese SMEs. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 13(4), 311-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2015.1090267

Singh, D. A., & Gaur, A. S. (2013). Governance structure, innovation and internationalization: evidence from India. Journal of International Management, 19(3), 300-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2013.03.006

Soler, I. P., Gemar, G., & Guerrero-Murillo, R. (2017). Family and non-family business behaviour in the wine sector: a comparative study. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1-2), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejfb.2017.11.001

Stenholm, P., Pukkinen, T., & Heinonen, J. (2016). Firm growth in family businesses — The role of entrepreneurial orientation and the entrepreneurial activity. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(2), 697-713. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12166

Thomas, J., & Graves, C. (2005). Internationalization of the family firm: the contribution of an entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 17(2), 91-113.

Tolba, A., Meshreki, H., & Kolaly, H. E. (2020). Family business innovation and coping mechanisms following the covid-19 disruption. Submitted to the conference Family Business in the Arab World.

Vanyushyn, V., Bengtsson, M., Näsholm, M. H., & Boter, H. (2018). International coopetition for innovation: Are the benefits worth the challenges? Review of Managerial Science, 12(2), 535-557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0272-x

Verheul, I., & Van Mil, L. (2011). What determines the growth ambition of Dutch early-stage entrepreneurs? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 3(2), 183-207. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2011.039340

Wang, D., & Schøtt, T. (2020). Coupling between financing and innovation in a startup: embedded in networks with investors and researchers. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00681-y

Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

Williams Jr, R. I., Pieper, T. M., Kellermanns, F. W., & Astrachan, J. H. (2018). Family firm goals and their effects on strategy, family and organization behavior: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(S1), S63-S82. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12167

Yildirim-Öktem, Ö., & Selekler-Göksen, N. (2018). Internationalization of family business groups: content analysis of the literature and a synthesis model. European Journal of Family Business, 8(1), 45-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v8i1.4146

Zali, M. R., Faghih, N., Ghotbi, S., & Rajaie, S. (2013). The effect of necessity and opportunity driven entrepreneurship on business growth. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 7(2), 100-108.