European Journal of Family Business (2020) 10, 61-68

Abandoning Family Management - Analysis of the Effects on Exports

Aoife Hanleya, Joaquín Monreal-Pérez*b, Gregorio Sánchez-Marínbc

aDepartment of Economics, Kiel Institute for the World Economy & Christian Albrecht (Germany)

bDepartment of Management and Finance, University of Murcia (Spain)

cDepartment of Economics and Busines, University of Alcala (Spain)

Received 2020-08-07; accepted 2020-11-02

JEL CLASSIFICATION

M12, M14, M16

KEYWORDS

Family firm management, Management transition, Export propensity

CÓDIGOS JEL

M12, M14, M16

PALABRAS CLAVE

Gestión de empresas familiares, Transición de gestión, Propensión a exportar

Abstract Finding the internationalization triggers of family-managed firms is not easy because family-managed firms are regarded as being very different to begin with (e.g. Bloom et al., 2011). In investigating the role of family management, we apply a Spanish sample of 805 family-managed firms to investigate the impact of abandoning family management on export propensity. Applying both logit and tobit models, we find the abandonment of family management is associated with a fall in export activity (both in export propensity and in export intensity), findings we relate back to managerial theories of the firm. This finding is related to specific features of family managed firms that favour export activity such as greater flexibility and altruism. The conclusions of this work have a number of relevant implications.

Abandonando la gestión familiar - Análisis de los efectos sobre las exportaciones

Resumen Encontrar los factores desencadenantes de la internacionalización de las empresas familiares no es fácil porque, para empezar, las empresas familiares se consideran muy diferentes (por ejemplo, Bloom et al., 2011). Al investigar el papel de la gestión familiar, aplicamos una muestra española de 805 empresas gestionadas por familias para investigar el impacto del abandono de la gestión familiar en la propensión a exportar. Aplicando modelos logit y tobit, encontramos que el abandono de la gestión familiar está asociado con una caída en la actividad exportadora (tanto en la propensión exportadora como en la intensidad exportadora), hallazgos que relacionamos con las teorías gerenciales de la empresa. Este hallazgo está relacionado con características específicas de las empresas familiares que favorecen la actividad exportadora como una mayor flexibilidad y altruismo. Las conclusiones de este trabajo tienen una serie de implicaciones relevantes.

https://doi.org/10.24310/ejfbejfb.v10i2.10099

Copyright and Licences: European Journal of Family Business (ISSN 2444-8788 ISSN-e 2444-877X) is an Open Access research e-journal published in Malaga by UMA Editorial.

Except where otherwise noted, contents publish on this research e-journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Atribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

*Corresponding author

E-mail: jomonreal@um.es

1. Introduction

It is commonly said that one constraint undermining the performance of family firms, especially in relation to their international operations, is the lack of professionalism of family managers who direct the firm (Samara et al., 2018). This lack of professionalism may be minimized by some factors, such as previous managerial experience. In this context, Geldres et al. (2016) and Casillas and Moreno-Menéndez (2017) review an extensive literature stressing the role of knowledge acquired by the firm’s managers, particularly in export markets and their presence in international networks.

Accordingly, this question of family firms and internationalization deserves further attention. According to the research line followed by Monreal-Pérez and Sánchez-Marín (2017), we endeavour to answer a closely connected question - should we expect that firms remaining under family-management will experience a higher export activity (both export propensity and export intensity) than firms which depart from family management? We argue that the answer may be yes. Our reasons are twofold. The first reason to expect differences in the export activity of family-managed and firms not under family management, has to do with the characteristics of firms guided by family members – the higher flexibility and trustworthiness of such firms (Casillas et al., 2010; Kontinen & Ojala, 2010, 2011; Merino et al., 2015; Segaro, 2010). Strengthening this argument, the Stewardship Perspective (SP) states that the long-term perspective of family firms and their perceived higher social capital and commitment are traits which favour exports (Davis et al., 1997; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Miller et al., 2008).

Despite extensive work in the internationalization literature on family firms and how their governance might impact internationalization (Alayo et al., 2020; Casprini et al., 2020; De Massis et al., 2015), no study has yet demonstrated what happens when a family firm decides to abandon or retain family control of the business.

We answer this question using a panel of 805 firms, 61 of which changed their management status during the period 2012-2013. The data was extracted from the Encuesta Sobre Estrategias Empresariales (ESEE) – an annual survey of Spanish firms. Using a Logit technique, we find that abandoning family management implies a fall in export propensity, contrary to the view that the lack of professionalism of family managers is detrimental to exporting (Arregle et al., 2017), given the perception that family firms tend to hire family members regardless of their abilities (Samara et al., 2018).

Our paper is set up as follows. We first outline the theoretical framework before formulating our testable hypothesis. Then, we present our research methodology before describing our data, the variables used and the econometric model. This is followed by the analysis section before we conclude in a final section.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Proposal

Do certain management modes within small firms encourage exporting? The management of firms is just one characteristic which is attracting increased attention from economists (e.g., Bloom et al., 2011). Yet, Benavides-Velasco et al. (2013) have pointed out that the internationalization of firms is one source of differences between firms and the way they are managed, a point that researchers need to consider in their work.

Despite the accumulating literature on the relationship between family managed firms and internationalization, there is a lack of consensus about whether family managed firms are more likely to export. A number of recent reviews have been published so far about the relationship between family firms and internationalization (Alayo et al., 2020; Arregle et al., 2017; Casillas & Moreno-Menéndez, 2017; Casprini et al, 2020; Kontinen & Ojala, 2010; Metsola et al., 2020).

For example, whereas some studies (Kontinen & Ojala, 2011) find that the small size and flexibility of management teams in family firms allow them to react quickly to new international opportunities, others (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2008) conclude that family firms exhibit lower levels of internationalization than non-family firms due to their concern with preserving the family control of the business. These contradictory results have possibly to do with the different characterization of family governance, research methodology and samples used.

The Stewardship Theory (Davis et al., 1997; Miller et al., 2008) and the Socioemotional Wealth (SEW) Theory (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, 2011) both have a lot to say on the subject of risk-taking, in general, and more specifically on the type of risk-taking which is associated with selling products on foreign markets and drawing on skills which the current family-managers do not possess.

Overall these theories are ambiguous regarding the overall willingness to export of family- vs. non family-managed firms. From the SEW perspective (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, 2011), it is our expectation that family managed firms favour a reduction in exporting since families are keen to retain their grip on management.

Nevertheless, we rely more on the Stewardship Perspective (SP) that predicts an exporting premium to family-managed firms if the long-term perspective of such firms and their perceived higher social capital and commitment help them to enter new overseas markets (Davis et al., 1997; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Miller et al., 2008).

Moreover, Kontinen and Ojala (2011) show that the small size and the flexibility of the management team within family-managed firms help them to respond quickly to new international opportunities. Studies based on the Stewardship Perspective predict that resource shortcomings for family-managed vs. non family-managed firms are more than compensated by higher family specific resources, like trust, altruism, social capital and network ties (Casillas et al., 2010; Merino et al., 2015; Segaro, 2010).

In this vein, Merino de Lucas et al. (2015) argue that maintaining a family perspective may explain why family firms are more internationalized than their non family counterparts. Specifically, these authors find that it is the culture dimension (the connectedness between the firm’s members with the values of the firm) which makes it easier for family firms to export.

Taking all these arguments into account, we predict that family management may favour the firm export activity, arguing that the change from family management to non family management may restrain the firm export activity. This leads us to propose the following two hypotheses:

H1: The abandonment of family management (to non family management) implies a fall in the firm’s export propensity

H2: The abandonment of family management (to non family management) implies a fall in the firm’s export intensity.

3. Methodology

In the section that follows, we first present a logit model which takes export propensity as the relevant outcome. Secondly, we introduce our model for export intensity, applying a tobit model. Finally, we present our sample and data, describing each measure used.

3.1 Logit and tobit method

Our methodology applies first a logit and then a tobit approach, depending on the nature of the dependent variable. For binary-categorical dependent variables, such as export propensity, the logit model is favoured, while for export intensity (a continuous measure), Tobit is the preferred choice. For the case when a dummy is the dependent variable (as in our case, Export Propensity) linear probability models (LPM) like the logit one, are the most widely used models for estimating the functional relationship, while when the estimated probability values fall outside the range of “0” and “1” because the dependent variable is a quantitative one, the Tobit model allows us derive consistent and asymptotically efficient predictors (Güneri & Durmus, 2020).

Our most important variable of interest (see also Section 3.3 below), Abandon, is coded as 1 for a firm which departed from family management in the 2012/2013 period. Otherwise, it is coded as 0.

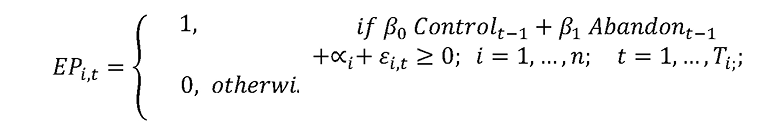

One advantage of the Logit estimation is that it is very straightforward to use and more directly comparable with other studies. The model specification is as follows:

Where EPi,t represents the export propensity of firm i in period t; the control variables (i.e., age, size, and R&D invests, all within the period t-1); the explanatory variables corresponding to the firm i during period t-1 are “Abandon” (defined as the switch from a top-management team which includes a family member to a total absence of any family member in the team). αi captures the unobservable differences among the firms; and finally, εit is the error term. We assume that αi and εit are uniformly, independently and normally distributed, with a mean of zero and variances of and

, respectively. Additionally, we assume that αi and εit are independent of (xi1, xi2,…, xiT). It is important to consider only family managed firms in our analysis.

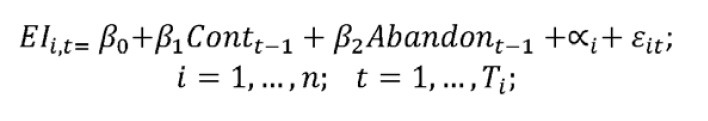

Secondly, the consideration of Export Intensity (EI) as the dependent variable suggests a tobit specification with the same explanatory variables appearing in the logit model, whose form is:

Again, only family managed firms are considered.

3.2. Sample and data description

We first describe the data that we used to estimate the relationship between abandoning family-management and exporting before examining individual variables featured in our analysis.

Our study focuses on a sample of Spanish firms from the well-known database Encuesta Sobre Estrategias Empresariales (see also Caldera, 2010; Merino et al., 2015).

The Encuesta Sobre Estrategias Empresariales (ESEE) which translates as the Survey of Spanish Business Strategies, is an institutional database (compiled by the Spanish Ministry Industry and the SEPI Foundation) annual survey. It elicits over 100 questions in an annual survey which is administered to about 1,800-2,000 firms comprising over 10 employees. The ESEE takes a broad sample of firms each year and on average has a response rate of 90 percent.

From the ESEE database, for the period 2012-2014, we extracted a sufficiently large sample of firms that departed from family management. Management (most stringent definition) implied that the family owning the busines, also exercised control over its daily operations. We managed to obtain a sample of 61 firms which departed from family management in the 2-year period 2012 to 2013 and whose export incidence was subsequently recorded for 2014.

3.3. Variables

Here we define each of our variables in turn.

Family managed firm. Our definition of family managed firm depends on the likely involvement of family members in decision making (Fernandez & Nieto, 2005). Moreover, we believe that if the firm is managed by at least one family member (Banalieva & Eddleston 2011; Faccio & Lang, 2002), such a decision is also likely to correlate with active involvement in the firm’s operations (Chrisman et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010). Thus, we coded family firm as a dummy variable which takes the value 1 when a familiar group is actively involved in the management of the firm and 0 otherwise.

Abandon (Firms leaving family-management). We approach this question in two ways. In the first way, we examine a subset of firms which started out being family owned in the years 2012 and 2013 (‘fam’ = 1). Over this two year period, some of these firms shift away from family management (‘fam’ = 0). We then end up with a variable called Abandon (coded 0 for 744 firms which remain under family-management and coded as 1 for the 61 firms which depart from family-management). This variable is included in the Logit regression to help explain exporting in the 2014 period.

Export activity. Following previous studies on business internationalization (Fernández & Nieto, 2005; Katsikeas et al., 2000), we measure the firm’s export activity by assessing both the firm’s export propensity (which is a categorical variable that indicates whether a firm has exported during the period under consideration) and the export intensity (percentage of exports to total sales).

Control variables. In our Logit estimation we use a set of covariates which are shown in other studies and the literature to explain the firm’s export propensity (see Sousa, 2008, for a detailed review of such determinants). Accordingly, three control variables were employed:

First, firm size corresponding to the firm’s total number of employees at year end; second, firm age which is simply the number of years since the firm was incorporated, and finally R&D, that is the percentage which represents total expenses on R&D to sales volume.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

Our data which is taken from the Spanish ESEE. We now describe this sample in greater detail1:

Table 1: Description of the sample

|

Export propensity |

Export intensity |

Age |

Size |

R&D |

|

|

Abandon family management (n = 61; 7,6%) |

0.6037736 |

0.2031524 |

31.74286 |

97.98361 |

0.0061035 |

|

Retain Family Management (n = 744; 92.4%) |

0.658147 |

0.2462038 |

31.13758 |

65.56891 |

0.0061238 |

|

Total (n = 805; 100%) |

0.6540084 |

0.2108989 |

31.31608 |

69.05913 |

0.0063691 |

1Only family managed firms are selected.

As can be seen in Table 1, family managed firms that abandon family management export less than firms that remain family managed. This drop confirms our expectations in H1 and H2 given by the SP and is contradictory to the usual belief that family managed firms export less due to their lack of professionalism (Samara, 2018). To estimate these impacts more, we rely on the Logit estimation results.

Accordingly, we show the correlation values of the variables contained in the Logit (Table 2) and Tobit regressions, respectively (Table 3):

Table 2: Pairwise correlation1 (export propensity as dependent variable)

|

Export propensity |

Abandon |

Size |

Age |

R&D |

|

|

Export propensity |

1.0000 |

||||

|

Abandon |

-0.0307 |

1.0000 |

|||

|

Size |

0.1967* |

0.0522 |

1.0000 |

||

|

Age |

0.2110* |

0.0090 |

0.1757* |

1.0000 |

|

|

R&D |

0.1584* |

-0.0002 |

0.1116* |

0.0817 |

1.0000 |

1Only family managed firms are selected.

*p < 0.05.

Table 3: Pairwise correlation1 (export intensity as dependent variable)

|

Export intensity |

Abandon |

Size |

Age |

R&D |

|

|

Export intensity |

1.0000 |

||||

|

Abandon |

-0.0190 |

1.0000 |

|||

|

Size |

0.1835* |

-0.0337 |

1.0000 |

||

|

Age |

0.1784* |

-0.0058 |

0.1389* |

1.0000 |

|

|

R&D |

0.1492* |

-0.0166 |

0.1352* |

0.0488 |

1.0000 |

1Only family managed firms are selected.

*p < 0.05.

As can be seen in Table 2 and Table 3, all the values lie below 0.56, which is the maximum value recommended for the test of multicollinearity (Leiblein et al., 2002). In addition, to evaluate the impact of these correlations, we tested for the variance of inflation (VIF)1 resulting in a maximum of 1.05, indicating the absence of multicollinearity (Baum, 2006).

4.2. Estimation results

First, we estimate a panel Logit model to explain the post-transition differences in export propensity between family-managed firms and those which depart from family management. All covariates are expressed at the firm-level.

Table 4. Logistic regression results

|

Dependent variable: export propensity |

||||

|

Coefficent |

Standard error |

z |

P >|z| |

|

|

Abandon |

-0.8393089 |

0.4403559 |

-1.91 |

0.057 |

|

Size |

0.0219777 |

0.0038701 |

5.68 |

0.000 |

|

Age |

0.0200925 |

0.0076633 |

2.62 |

0.009 |

|

R&D |

26.84353 |

11.25637 |

2.38 |

0.017 |

|

Constant |

0-.839386 |

0.2495291 |

-3.36 |

0.001 |

|

N |

521 |

|||

|

LR chi2 (Prob > chi2) |

112.72 (0.0000) |

|||

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.1688 |

|||

|

Log likelihood |

-277.52601 |

|||

Secondly, and identically that what has been done above, we estimate a panel tobit model to explain the post-transition differences in export propensity between family-managed firms and those which depart from family management.

As Table 4 and Table 5 show, the results for our logit and tobit estimation reveal that firms which depart from family-management are less likely to export in the future. This result, at face value, ties in with the results for the summary statistics in Table 1. We recall from Table 1 that generally firms under family-management were seen to be more likely to export and with a higher intensity than firms which abandoned family-management. This result supports our two research hypotheses.

We can briefly comment on the other covariates in the regression model. Unsurprisingly, firms with positive exporting (lagged) are more likely to export into the future. The other covariates behave as expected and in a way consistent with other studies (Barrios et al., 2003; Greenaway and Kneller, 2008; Sousa et al., 2008; Wagner, 2001). Size, age and R&D activity are correlated positively with future exporting.

Table 5. Tobit regression results

|

Dependent variable: export intensity |

||||

|

Coefficient |

Standard error |

z |

P >|z| |

|

|

Abandon |

-0.4172353 |

0.2529524 |

-1.65 |

0.099 |

|

Size |

0.0086395 |

0.0014254 |

6.06 |

0.000 |

|

Age |

0.0110927 |

0.0040807 |

2.72 |

0.007 |

|

R&D |

13.06677 |

5.153519 |

2.54 |

0.011 |

|

Constant |

-0.3396389 |

0.1350802 |

-2.51 |

0.012 |

|

N |

521 |

|||

|

LR chi2 (Prob > chi2) |

98.02 (0.0000) |

|||

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.1468 |

|||

|

Log likelihood |

-284.87859 |

|||

5. Conclusions and Implications

Family management is often said to constrain the performance of firms. It is argued that family members are selected for management roles, not necessarily on the basis of their competence but due to their privileged position as members of the business owner’s family (Samara et al., 2018). Moreover, from the SEW perspective (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, 2011), it is argued that family managed firms decrease their exporting since families want to maintain their grip on management. We explore these arguments, searching for evidence of these predicted effects in our sample.

What we find is that firms that abandon family management experience a drop in their export propensity. A possible explanation for these differences in export propensity is the Stewardship Perspective that small and flexible family-managed firms are better equipped to respond quickly to international opportunities.

Moreover, lack of appropriate experience is argued to be one of the factors suggesting a lack of professionalism among family managers (Geldres et al., 2016). This argument is in line of the study of Merino de Lucas et al. (2015) which departs from the family perspective, showing how the experience dimension is one of the main drivers of the internationalization of family firms.

In results which tie in with the above explanation, Sánchez-Marín et al. (2020) argue that greater family involvement in management can underline the family firm’s desire for long-term survival, eventually overcoming the risk aversion linked to internationalization, and so positively influencing the firm’s likelihood of exporting and developing new products (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010).

Not only is the group of firms which depart from family management likely to contain within-group heterogeneity, so also is the Abandon group. This is because family-management represents a continuum which runs from moderate family-ownership to high family-ownership (Naldi

& Nordquist, 2008) and the differences in the degree to which the family influences the day-to-day operations of the business influence the firm’s export behaviour (Merino et al., 2015; Sánchez-Marín et al. 2020). However, a goal for future research might be to replicate the analysis while controlling for further sources of group heterogeneity within the group of firms which leave family management. What are the broader implications our findings? Specifically, Sciascia et al. (2012) show that international behaviour follows an inverted U-shape depending on the extent of family influence within the firm’s ownership structure: moderate family ownership favours internationalization, but when such ownership is extremely high, this is unhelpful to internationalization.

Moreover, it would be interesting to regard our export findings through a different lens – that of authority and the ultimate goals of family businesses. Through a learning process, family firms, given the owners’ higher authority, wealth concentration and pursuit of nonfinancial goals, are able to more efficiently leverage their exposure to foreign markets (Freixanet et al., 2018, 2020).

A further issue that needs to be explored in future work is dealing with the internationalization of family businesses over time. Since internationalization and family management are dynamic concepts (Metsola et al., 2020), it would be interesting to investigate the impact of switching from family management over time.

Despite its limitations, our study should be viewed as a first attempt to explore some of the dynamics behind a firm’s decision to leave family-management and the impacts on the firm’s subsequent export status.

Why is our finding relevant for industrial policy in Europe where firms are struggling to compete in a period of economic recovery? To say anything meaningful about policy, we need to understand some the wider economic context for the Spanish firms on which our analysis is based. After a period of shrinking GDP due to the COVID-19 crisis and of high unemployment (spiralling to 20-25 percent), selling abroad has become an imperative for firms which need to compensate for sluggish domestic demand. The growth of Spain’s major trading partners such as Germany is seen as an important stimulant to Spain’s exporters.2

Our finding that firms moving from family-management experience a drop in export propensity and intensity comes at an important time for Spain’s enterprises. This is especially true, when we attempt to understand the impact of managerial shifts within firms. Researchers such as Benavides-Velasco et al. (2013) have pointed out that the internationalization of firms is a consequence of the uniqueness of these firms. In a framework which seeks to control for some of these selection effects, we have demonstrated that family management exercises a significantly positive impact on a firm’s internationalization activities.

References

Alayo, M., Iturralde, T., Maseda, A., & Aparicio G. (2020). Mapping family firm internationalization research: Bibliometric and literature review. Review of Managerial Science, in press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00404-1

Arregle, J.-L., Duran, P., Hitt, M. A., & van Essen, M. (2017). Why is family firms’ internationalization unique? A meta-analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(5), 801-831. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12246

Banalieva, E. & Eddleston K. A. (2011). Home-region focus and performance of family firms: The role of family vs non-family leaders. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(8), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.28

Barrios, S., Görg, H., & Strobl, E. (2003). Explaining firms’ export behaviour: R&D, spillovers and the destination market. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(4), 475-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00058

Baum, C. F. (2006). An introduction to modern econometrics using Stata. Texas: Stata Press.

Bhaumik, S. K. & Gregoriou, A. (2010). Family ownership, tunnelling and earnings management: A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 24(4), 705-730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00608.x

Benavides-Velasco, C. A., Quintana-García, C., & Guzmán-Parra, V. F. (2013). Trends in family business research. Small Business Economics, 40, 41-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9362-3

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2011). Keeping family-owned firms family-run from one generation to the next can be bad for business. British Politics and Policy at LSE.

Casillas, J. C. & Moreno-Menéndez, A. M. (2017). International business & family business: Potential dialogue between disciplines. European Journal of Family Business, 7(1-2), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejfb.2017.08.001

Casillas, J. C., Moreno, A. M., & Acedo, F. J. (2010). Internationalization of family businesses: A theoretical model based on international entrepreneurship perspective. Global Management Journal, 2(2), 18-35.

Casprini, E., Dabic, M., Kotlar, J., & Pucci, T. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of family firm internationalization research: Current themes, theoretical roots, and ways forward. International Business Review, 29(5), 101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101715

Caldera, A. (2010). Innovation and exporting: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Review of World Economics, 146, 657–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-010-0065-7

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family-centered non-economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, D. F., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Towards a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22, 20–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/259223

De Massis A., Kotlar J., Campopiano G., & Cassia L. (2015). The impact of family involvement on SMEs’ performance: Theory and evidence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 924–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12093

Esteve-Pérez, S. & Rodríguez, D. (2013). Exports and R & D. Small Business Economics, 41, 219-240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9421-4

Faccio, M. & Lang, L. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65(3), 365–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00146-0

Fernández, Z. & Nieto, M. J. (2005). Internationalization strategy of small and medium-sized family businesses: Some influential factors. Family Business Review, 18, 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2005.00031.x

Freixanet, J., Monreal, J., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2018). Leveraging new knowledge: The learning-by-exporting effect on leading and lagging family firms. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), 14923.

Freixanet, J., Monreal, J., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2020). Family firms’ selective learning-by-exporting: Product vs process innovation and the role of technological capabilities. Multinational Business Review, in press. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBR-01-2020-0011

Geldres, V., Uribe, C. T., Coudounaris, D. N., & Monreal-Pérez, J. (2016). Innovation and experiential knowledge in the firm exports - Applying the initial U-model. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5076–5081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.083

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & De Castro, J. (2011). The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Academy of Management Annals, 5, 653-707. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.593320

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K., Nuñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 106-137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Makri, M., & Larraza-Quintana, M. (2010). Diversification decisions in family-controlled firms. Journal of Management Studies, 47, 223-252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00889.x

Greenaway, D. & Kneller, R. (2008). Exporting, productivity and agglomeration. European Economic Review, 52(5), 919-939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.07.001

Güneri, Ö. I. & Durmuş, B. (2020). Dependent dummy variable models: An application of logit, probit and tobit models on survey data. International Journal of Computational and Experimental Science and Engineering, 6(1), 63-74.

Hamelin, A. (2013). Influence of family ownership on small business growth. Evidence from French SMEs. Small Business Economics, 41, 563-579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9452-x

Hanley, A. & Monreal-Pérez, J. (2012). Are newly exporting firms more innovative? Findings from matched Spanish innovators. Economics Letters, 116, 217–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.03.006

Katsikeas, C. S., Leonidou, L. C., & Morgan, N. A. (2000). Firm-level export performance assessment: Review, evaluation, and development. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4), 493-511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300284003

Kontinen, T. & Ojala, A. (2010). The internationalization of family businesses: A review of extant research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1, 97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2010.04.001

Kontinen, T. & Ojala, A. (2011). International opportunity recognition among small and medium-sized family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 49, 490–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00326.x

Leiblein, M. J., Reuer, J. J., & Dalsace, F. (2002). Do make or buy decisions matter? The influence of organizational governance on technological performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9), 817-833. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.259

Merino de Lucas, F., Monreal-Pérez, J., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2015). Family SMEs’ internationalization: disentangling the influence of familiness on Spanish firms’ export activity. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 1164-1184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12111

Metsola, J., Leppäaho, T., Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E., & Plakoyiannaki, E. (2020). Process in family business internationalization: The state of art and ways forward. International Business Review, 29(2), 101665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101665

Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Públicas de España (2014). Presentación del Proyecto de Presupuestos Generales del Estado 2014. Secretaría de Estado de Presupuestos y Gastos, Madrid.

Miller, D. & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 51-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00718.x

Monreal-Pérez, J., & Sánchez-Marín, G. (2017). Does transitioning from family to non-family controlled firm influence internationalization? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(4), 775-792. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2017-0029

Naldi, L. & Nordquvist, M. (2008). Family firms venturing into international markets: A resource dependence perspective. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 28(14), 1-18.

Pukall, T. J. & Calabrò, A. (2014). The internationalization of family firms: A critical review and integrative model. Family Business Review, 27(2), 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486513491423

Samara, G., Jamali, D., Sierra, V., & Parada, M. J. (2018). Who are the best performers? The environmental social performance of family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 9(1), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2017.11.004

Sánchez-Marín, G., Pemartín, M., & Monreal-Pérez, J. (2020). The influence of family involvement and generational stage on learning-by-exporting among family firms. Review of Managerial Science, 14(1), 311-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00350-7

Sciascia, S., Mazzola, P., Astrachan, J. H., & Pieper, T. (2012). The role of family ownership in international entrepreneurship: Exploring nonlinear effects. Small Business Economics, 38, 15-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9264-9

Segaro, E. (2010). Internationalization of family SMEs: The impact of ownership, governance, and top management team. Journal of Management and Governance, 14, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-010-9145-2

Sousa, C. M. P., Martínez-López, F. J., & Coelho, F. (2008). The determinants of export performance: A review of the research in the literature between 1998 and 2005. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(4), 343-374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00232.x

Wagner, J. (2001). A note on the firm size–export relationship. Small Business Economics, 17(4), 229-237. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012202405889

Notas

1. Maximum VIF for each independent variable: Abandon=1.00; R&D expenditure=1.03; Firm age=1.02; Firm size=1.05

2. Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Públicas de España 2014; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013.