Sometimes artworks possess an uncanny ability to transport us through what feels like a tunnel in time. In their physical presence they appear to address us in the present moment, yet they often contain surprises that escape the human eye—either because they are present but remain unnoticed, or because they can be sensed without leaving visible traces. Within this temporal passage we encounter moments of anachronism in which no light seems visible at the end, and others in which we may situate ourselves within the creative space itself: as participants in history, as protagonists, or as curious spectators to whom the past speaks from beyond its own limits.

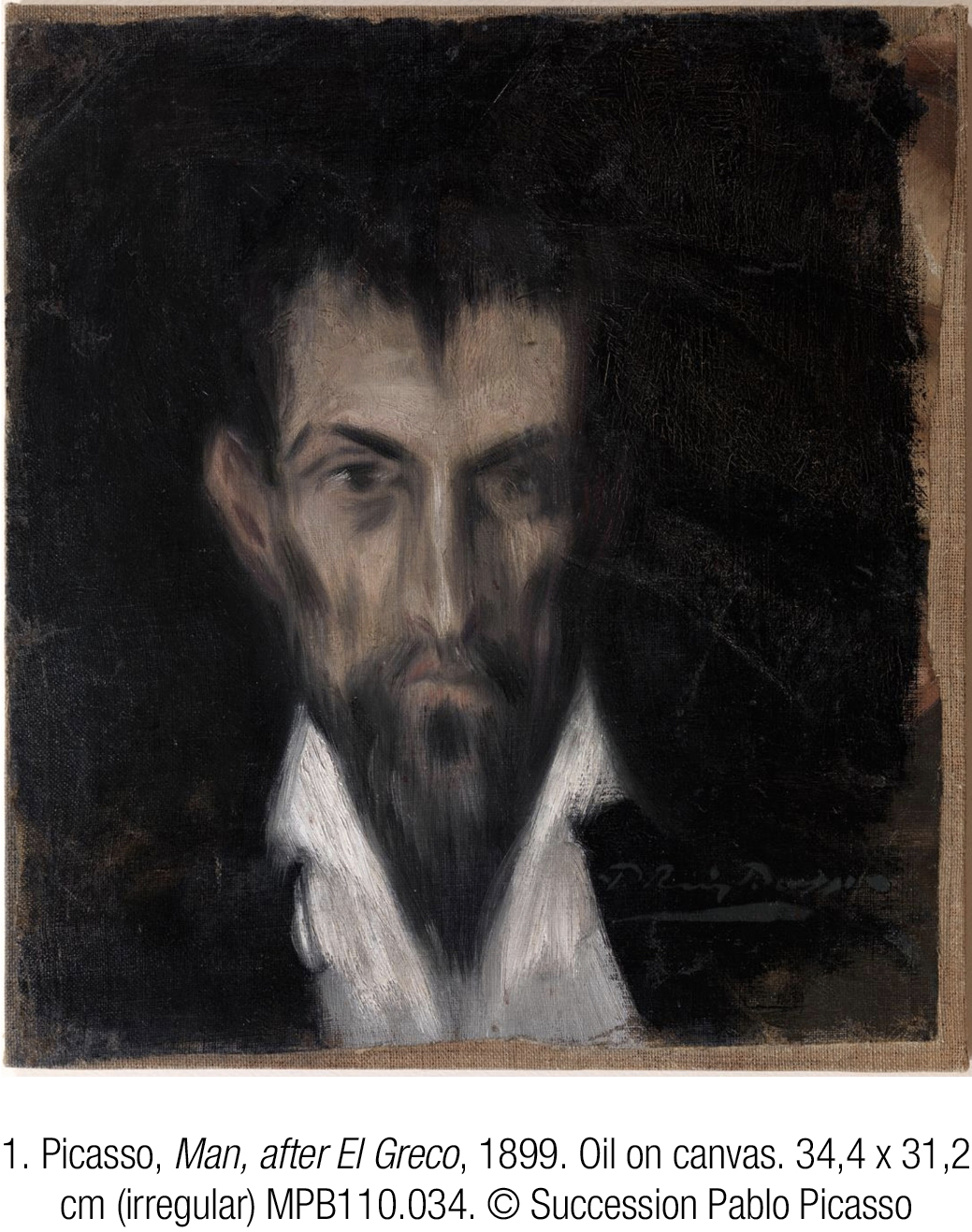

This invites us to reconsider the boundaries of time: beneath the final layer of paint on a masterpiece there may lie something quite different—an earlier image that alludes to another work, reinterpreting it in turn. This is precisely the case with what I shall call Picasso’s «triple portrait». In this article, I reveal for the first time the hidden surprise uncovered in Picasso’s well-known anonymous portrait Man, after El Greco [1], painted in Barcelona in 1899, and made visible through a recent radiographic study.

This analysis proposes that Picasso’s painting embodies the identities of three distinct yet interconnected artists. Although not a literal triple portrait, the connection resides in the deeper domain of creative expression: the artistic legacies of Picasso, El Greco, and Velázquez persist through history, interwoven through what the German art historian Aby Warburg termed Nachleben—the afterlife or survival of forms. We shall begin by examining the historical context of the work, then consider the painting itself, and finally articulate our main thesis: a new reading of the young Málaga-born artist.

I

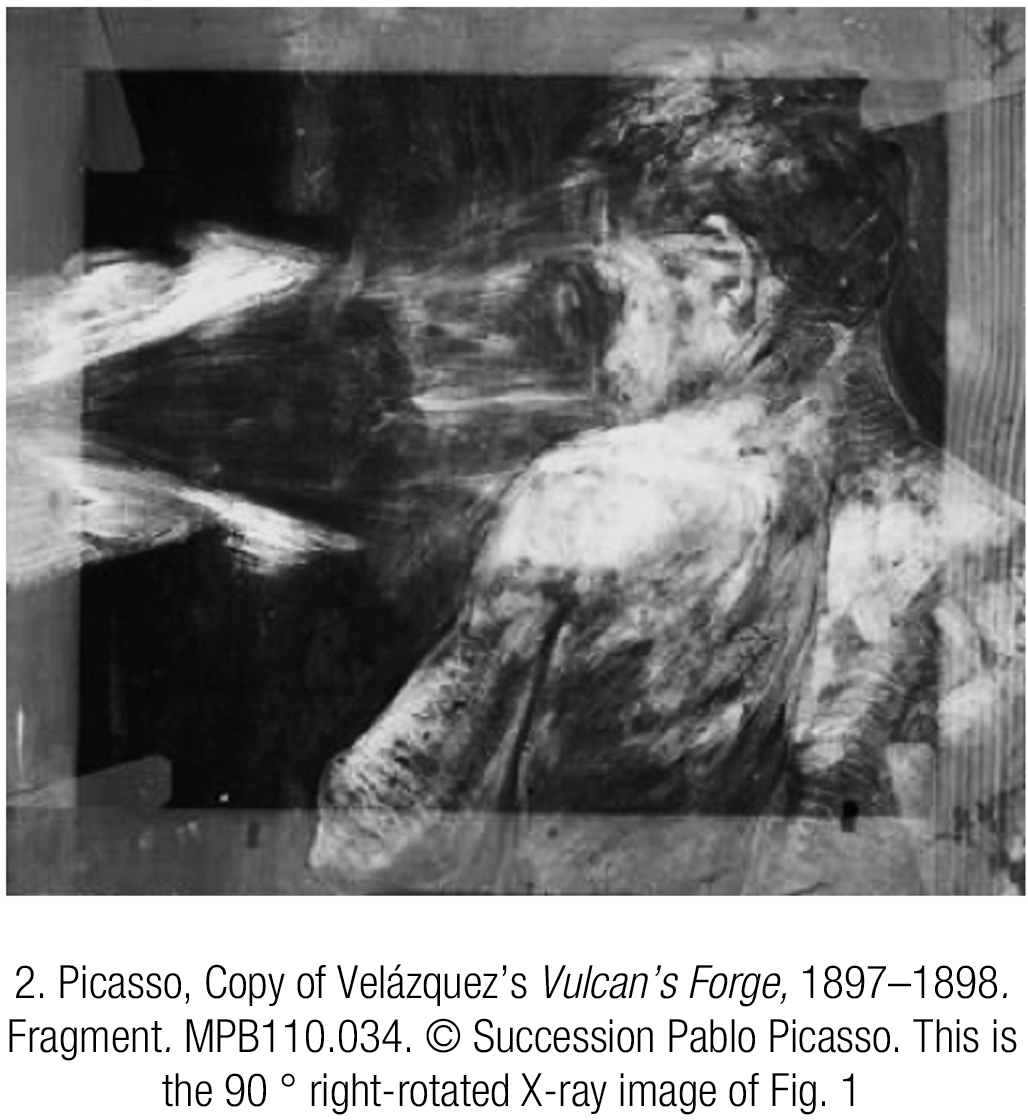

A collaboration between art and science—radiography conducted in 2015 by a team of conservation specialists—allows us to identify what had long been unknown in one of Picasso’s earliest works (Sessa et al., 2016). X-ray imaging, functioning as a laboratory for visual investigation, enables us to explore the relationship between Picasso’s early fascination with classical masterpieces and the formation of his own artistic identity.

Examining the X-ray image of Man, after El Greco rotated 90° to the left [2], we discern a fragment of a larger academic drawing akin to those Picasso produced during his studies at La Llotja. The scans confirm Picasso’s well-documented practice of reusing canvases (Hoenigswald, 1997). Before turning to the works themselves, a brief historical overview is required.

On 3 November 1897, Picasso wrote to Joaquim Bas, a friend from La Llotja, articulating his artistic aspirations and newly adopted role models: «The museum of paintings [Museo del Prado] is very nice indeed: “(…) El Greco has some magnificent heads. Velázquez is first-rate”» (Picasso, 1897). A year later, whilst staying in Horta de Sant Joan (southern Catalonia), he filled a sheet of sketches with inscriptions praising both painters—El Greco and Velázquez—as sources of inspiration [3].

The rediscovery of El Greco’s work proved pivotal for the development of painting in the final third of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth (Barón, 2014). Picasso saw El Greco’s celebrated Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest (c. 1580) (Museo Nacional del Prado, MNP, P000809)—a portrait that would later become emblematic of the Spanish caballero. This was in the autumn of 1897, when the young artist moved to Madrid to study at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. He soon rejected the Academy’s pedagogical methods and chose instead to learn directly from close study of the masterpieces of El Greco (1541-1614), Velázquez (1599-1660), and painters such as Murillo, Titian, Van Dyck, Rubens, and Teniers.

After Picasso’s early formative years in A Coruña, the Ruiz-Picasso family relocated to Barcelona in 1895. Working in his studio on Carrer dels Escudellers Blancs, he painted Man, after El Greco in 1899, clearly echoing both the Nobleman and several figures from El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586-1588) in Toledo. Picasso often visited Toledo on Sundays, when the Prado was closed.

II

This painting is an exercise in distortion. With his elongated oval face, domed forehead, receding hairline, heavy-lidded eyes, triangular beard, pronounced ears, and tense mouth, Picasso’s sitter bears a striking resemblance to El Greco’s stylized figures. The tightly fitted lace collar beneath the chin further recalls El Greco’s Portrait of a Gentleman (c. 1586, MNP, P000813) and the background figures of The Disrobing of Christ (1577–79, Toledo Cathedral).

Picasso learned from El Greco to look attentively, to notice the subtle irregularities of the unusual face. In his early portraits, figures often appear unsettled, with wide, staring eyes, melancholic gazes, or even slight strabismus—as if the world before them did not conform wholly to Euclidean geometry (Pijoan, 1930). Later, when Picasso revisited Velázquez’s Las Meninas through his 1957 Variation Series, he declared his wish to «un-learn» Velázquez: «I will try to do it in my way, forgetting about Velázquez» (Sabartés, 1957)—despite having once studied the Sevillian painter’s elegant classicism with great admiration.

Picasso entered the Academia de San Fernando in 1897. He copied Velázquez’s Philip IV (Museu Picasso Barcelona, MPB 110.017) and produced landscapes of the Retiro Pond (MPB 110.094, 110.227), attempting to capture the atmosphere reminiscent of Velázquez’s Roman-period works at the Villa Medici (1629-1630). He sketched copies of The Fable of Arachne, Las Meninas, and an equestrian portrait of Philip IV (MPB 110.398). He also drew an unmistakable caricature of an El Greco figure in his 1898 Madrid sketchbook (MPB 112.575).

The greatest surprise revealed by the radiograph, however, is the comparison between Picasso’s hidden male torso and Velázquez’s Vulcan’s Forge (1630), painted during his Italian sojourn [4]. That journey had a profound and lasting influence on Velázquez’s development. Vulcan’s Forge and Joseph’s Bloody Coat (El Escorial) are generally attributed to his first Roman period. The classical influence of Bolognese and Roman art—and of sculpture—on the young Velázquez (Mulcahy, 2005) appears clearly reflected in the nude torso beneath Picasso’s portrait.

The X-rays reveal not only a copied Velázquez torso but also the young Picasso still probing the vitality of a mature Velázquez—employing one of his classical compositional frameworks. Picasso recognized that Velázquez used the nude to create greater spatial depth than clothed figures allowed. Picasso did not need to travel to Rome: by copying Vulcan’s Forge, he absorbed many of the lessons Velázquez himself had learnt from Italian art and from studying Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel (Portús, 2014). In this sense, radiography brings together El Greco’s ‘magnificent heads’, a ‘first-rate’ Roman Velázquez, and Picasso’s own early anatomical explorations anticipating Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Thus, El Greco and Velázquez both informed Picasso’s development.

III

The radiographic image—a Velázquez torso beneath an El Greco-inspired surface—creates a historical interplay in which each work projects the other forward and backward in time. This is the logic of what I refer to as Pablo Picasso’s three-in-one portrait. Dialectically, the man seen ‘through El Greco’s eyes’ draws the past into the present, offering, anachronistically, Picasso as a ‘total’ artist.

Aby Warburg’s notion of Nachleben, or the survival of forms (Didi-Huberman, 2003), helps clarify this dynamic. Several layers of survival are at work:

1. In Madrid, Picasso copied numerous portraits by El Greco and Velázquez.

2. Man, after El Greco is painted in an El Greco-like idiom.

3. The torso beneath the portrait echoes the male figure in Vulcan’s Forge.

4. Before moving to Paris, Picasso drew deeply from both El Greco and Velázquez.

5. The visible portrait and the underlying Velázquez layer merge El Greco’s distortions with Velázquez’s Roman classicism on a single canvas.

How might Warburg’s idea of survival help explain what it means to ‘transcend temporal boundaries’?.

For Warburg, survival—the afterlife, continuity, and transformation of images and motifs—is the central problem of art history. Nachleben does not imply rebirth after extinction nor replacement by new forms. In Picasso’s painting, neither El Greco nor Velázquez has vanished. Hence the very notion of the triple portrait: the ‘triple presence’ of three artists linked by a kind of temporal threshold.

Chronological time—whether understood as influence or as a chain of facts—held little appeal for Warburg. He pursued instead a spectral, symptomatic notion of time. El Greco’s portraits belong to the chronology of Mannerism, Velázquez’s torso to the seventeenth century. Yet, for Warburg, these works are intelligible only when we recognize the anachronistic temporalities of the survivals they contain. Survival involves forgetting, transformation, involuntary memory, and unexpected rediscovery—processes that reveal a cultural, rather than natural, temporality (The Warburg Institute, 1931, 1938).

In my reading of Picasso’s El Greco-esque portrait, all these dynamics are present. A certain forgetfulness bridges the gap between the El Greco Picasso saw at the Prado and the distortions he adopted in the portrait he painted. Painting the new over the old—Velázquez’s torso—enacts a deliberate burial of the past. The transformation of meaning in both the Málaga and Sevillian painters becomes clear: the classics are brought into the fin de siècle, just as Picasso begins exploring the relationship between painting and reality. Involuntary memory plays its part: Picasso seeks to be himself, yet longs to learn from and be inspired by the masters. The rediscovery in 2015 of a hidden copy of Vulcan’s Forge underscores this dynamic of survival.

What emerges is a complex temporality —a play of pauses and crises, leaps and reversions— forming not a simple history but a web of memory, not a sequence of artistic facts but a theory of symbolic complexity. My hope is that this perspective resonates with admirers of historicism and with scholars of Picasso’s early work.