ANTONY: Eros, thou yet behold’st me?

EROS: Ay, noble lord.

ANTONY: Sometime we see a cloud that’s dragonish, A vapor sometime like a bear or lion, A towered citadel, a pendent rock, A forkèd mountain, or blue promontory With trees upon ‘t that nod unto the world And mock our eyes with air. Thou hast seen these signs. They are black vesper’s pageants.

EROS: Ay, my lord.

ANTONY: That which is now a horse, even with a thought The rack dislimns and makes it indistinct As water is in water.

EROS: It does, my lord.

Antony and Cleopatra, William Shakespeare. 1606.

ACT FOUR, Scene fourteen. Another room in the palace. Enter Antony and Eros.

In architectural interpretation, there is a maxim that was thought to be infallible. It consisted in applying the definition of myth: any story is better than no story.

It is important to point out, for the sake of obviousness, that this is not the definition of myth that is expected in Western tradition, and it should also be specified that this does not mean to say that the construction of criticism is always linked to mythical morphologies. I am adopting this definition out of coherence with the sense of displeasure we get from knowing we have been expelled from somewhere, be it from Christian Paradise or from Orthodox Modernity. Substitutive storytelling, parabolically or metaphorically, referring to something supposedly more important than the building itself, granted us intellectuality from the beginning and a tranquilising resolve to follow, with powerfully poetic examples in some cases and, in others, with irritation and annoyance at always looking the other way. Although the power of poeticisation remains huge, this does not mean one cannot disagree with it being used indiscriminately.

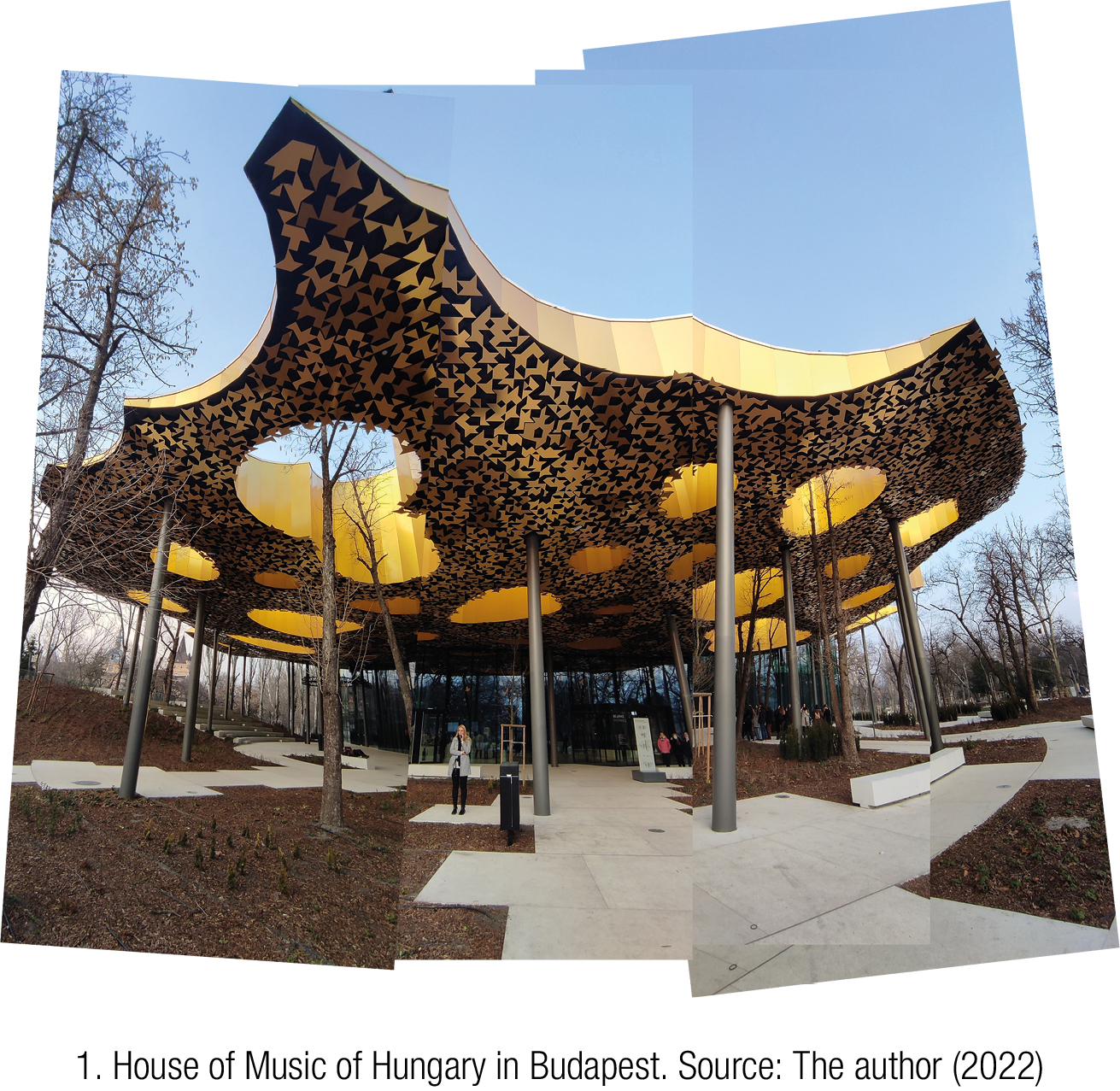

Bearing in mind that I can use this indirect narrative capacity without contradiction, I am able to more precisely state my thesis: that the House of Music by Sou Fujimoto in Budapest is not a cloud or a sea sponge, not a wild mushroom or a honey comb, not an omelette in a country picnic or a specular and weightless winter leaf, no matter how indomitable our associative sense may be, guiding us to any of these metaphors by some kind of uncontrollable mental, internal, more than visual, external anamorphosis.

When I say mental anamorphosis, I wish to argue – before its neological definition comes up – that denying the metaphor whilst metaphoring is a recurring trick among professional critics. For a critic, unlike for Shakespeare, a cloud, which could be all potency and no act, becomes the total, impotent act. Deforming something from a precise point of view entails an obscene self-absorption. In other words, it provides a static alternative focus diverting all attention.

The risk involved in a mere change of sign in the argumentative parameter – as to deny something does not prevent its counter-measure from being used here – is duly restricted in the cases at hand: We are talking about music, about architecture for music in the architecture of music. It is not about musical notation, since the immediate and recurring association would take us back to musical composition for architecture. It is something subtler and more beautiful still. Jean Luc Nancy (2003:73), resting in the Musica Ficta of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe (1991), links the destiny of Western music through the threshold of the parity between sense and significance, purportedly hyperexcited, by the sublime nature of the representation of sense.

The concept of sublime and representation seem not to belong on the same plane – it would be like measuring based on feeling, which proves paradoxically precise –, but it has to be expressed in this way to understand the step forward that music entails with its negative particle: over-significance, which in this context is the same as in- or a-significance. The fact that significance is present is no guarantee of sense; using it interpretatively or, in our case, projectually, should tend towards significancy, a field of openness, versus the closure that signifying implicitly imposes. Fujimoto had already put this into words in his debut in the Spanish language in 2009, when the journal 2G wrote a monograph on making an architecture composed of notes without a staff (2G, 2009).

A myth, in the conventional sense, consists in organising a guiding set of comprehensions and beliefs to very practically draw the relationship between human conscience and physical surroundings. Therefore, the myth sets the framework and lays down the terms to find, comprehend and shape social relations and the space surrounding them. Making an architectural interpretation would fit nicely into this action of myth. Hence the importance of choosing metaphors carefully and knowing when to use them. Being unable to recognise what we see activates the most primary connections in the brain, conjuring patterns we can compare to those stored in our basic memory.

That is the reason we see faces in formlessness and psychological disorders are diagnosed based on an inability to see them or on the atrocity envisioned.

This idea of recognising the formless is known as pareidolia. It is defined as a psychological phenomenon sparked by an imprecise, random visual stimulus that is erroneously perceived as a recognisable form based on a perceptive bias. In the cases we are discussing, it makes no difference whether they are intentional or not, in the projectual process or in the immersion and experience of spaces that have already been built. What does matter is the incapacity that comes with reiterating a procedure which mumbles prelinguistic sounds, despite the delight it brings us. Psychology states that in this mental mechanism termed pareidolia, information is processed in the subcortex, so it is a subconscious process that appears to precede better intellection. Its value lies in the speed at which it allows judgements and decisions to be made. This probably meant an evolutionary advantage helping to quickly envisage a predator in the undergrowth. Now that we no longer fear being hunted, this automatic ability is applied to new episodes, from the abstractions of Galdós to Arcimboldo’s vegetables or Victor Hugo’s ink blots, through to the depictions flooding the most visual social media to challenge our acuity.

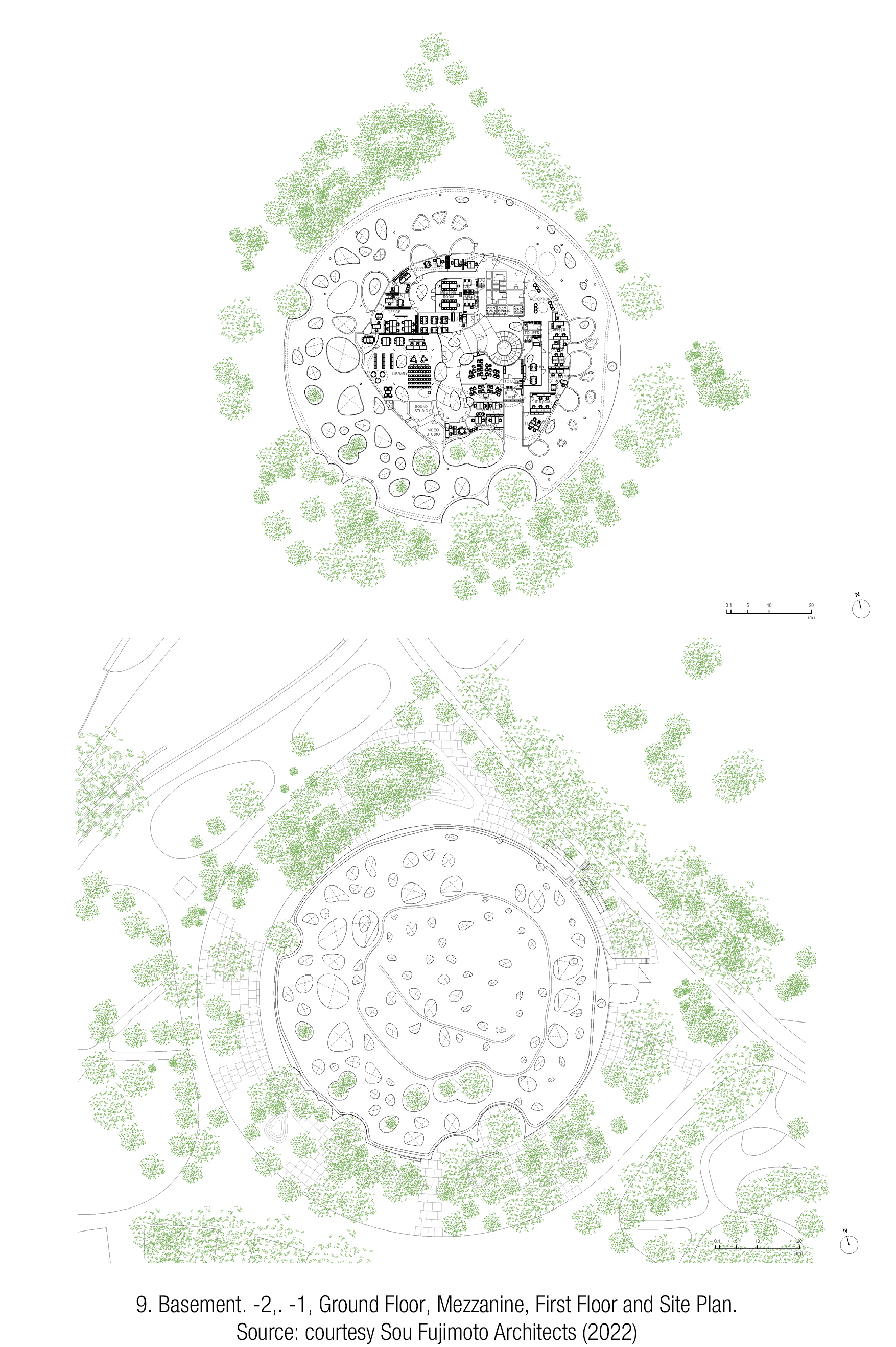

Going over the literature published by various architecture platforms and journals about the new House of Music in Budapest, we soon find references to what the architect himself says, mentioning some sort of noospheric connections drawn from the secessionist gold leaves plastered on the springings and spandrels of the vaulting inside the Liszt Academy (1061 Budapest, Liszt Ferenc ter 8), together with the formal play of the equally dazzling golden tesserae of the soffitto all along the building (City Park, Budapest, 1146, Olof Palme Sétány 3-5). Even the Academy logo created in 1907 by the architects Flóris Korb and Kálman Giergl takes this motif from the long formal repertoire shown both inside and out.

Social cognition builds the bridge between general perception and assessment of the outside world, which includes assessing social agents. Shortcomings in this capability lead to poor interpretation of social signs that are crucial for adaptive and effective interpersonal interactions. Processing faces and reading body language are two interlinked components of non-verbal communication that make up the core of social competence (Rolf et al, 2020:2). Therefore, when we are dealing with architecture and a stimulus cannot be processed, those bridge building mechanisms involve searching for links, genealogies, co-belongings. Nothing could be so new anymore that it comes into the world without being linked to an existent story.

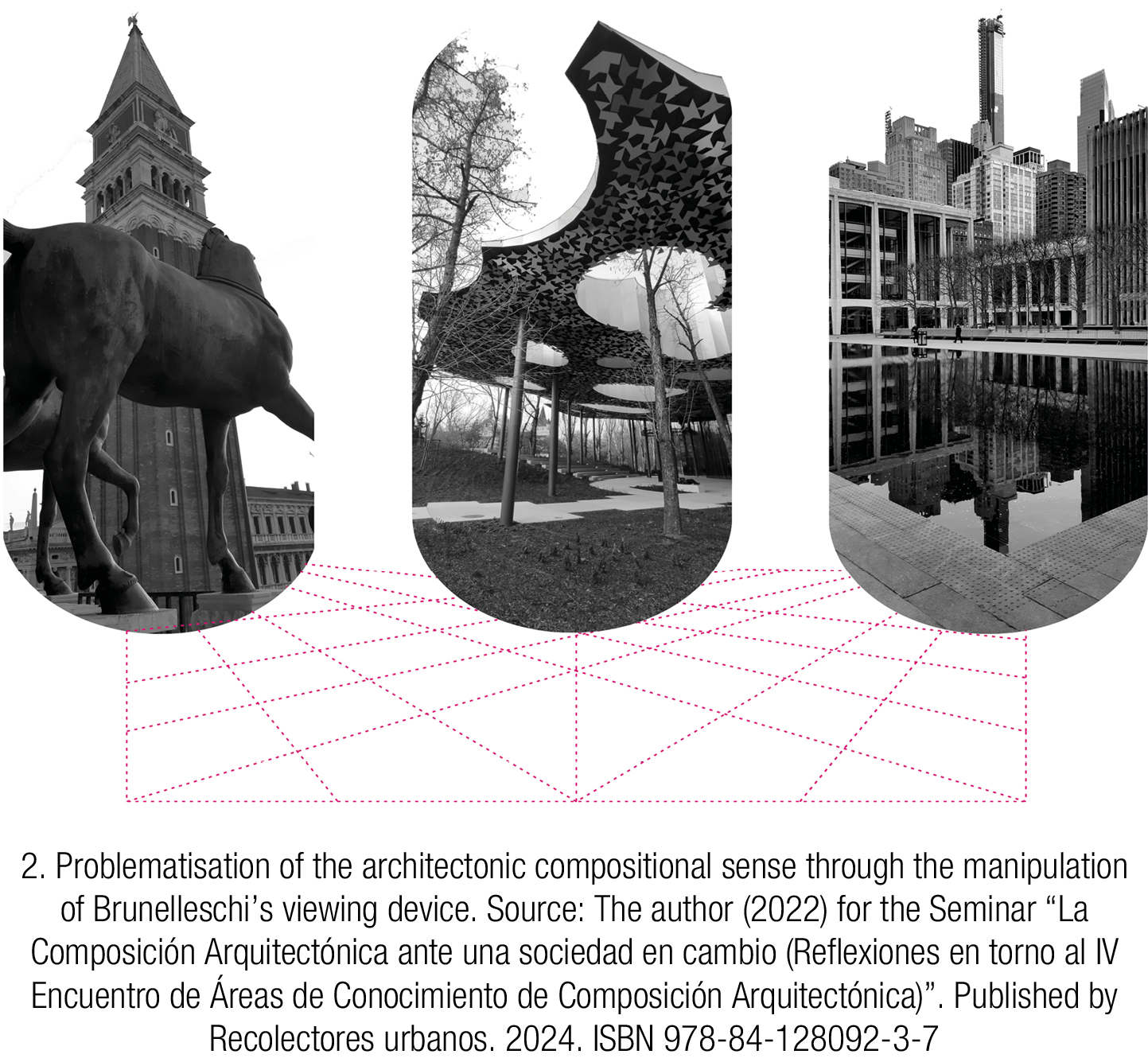

Assuming for a moment that this is true, let us situate Fujimoto’s building somewhere between classicity and modernity. The image below shows two distractive focal points, with the Piazza de San Marcos in Venice on the left and the Lincoln Center Plaza’s New York Philharmonic in on the right, placing Fujimoto’s building in the middle. On one side is the present with a past: Giorgio Spavento, Bartolomeo Bon, Baldassare Longhena, Scarpagnino, Vincenzo Scamozzi, Mauro Codussi, Lorenzo Santi, Jacopo Sansovino. On the other is the present threatened with the past: Robert Moses, Max Abramovitz, Pietro Belluschi, Gordon Bunshaft, Wallace Harrison, Philip Johnson, Elisabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio.

Squeezed between those positioned in history and the histories of those who are led to the past, there emerges an architecture that does not follow the statutory, standardised compositional evolutions that ought to be taught when an architect in the making studies architectural history and projection. The Asian ascription of this Japanese architect does not seem impervious to Western insertion in our postmodern clause (despite agreeing with Luis Fernández Galiano in that it is difficult to picture his work without his country’s social, technical and artistic surroundings, sharing some traits of the times, but with Sou Fujimoto, alongside Junya Ishigami, possibly being the most radical and the at the same time universalising of all). Therefore, this duality of distractive focal points calls for a more precise argumentation, which there is. Probably strongly influenced by the symbiosis of the East in the post-West following the fall of the Berlin Wall. However, I believe it is more important to make a reading – internally – from that post-Western gaze through which we see a building like the one we are interpreting. Hungary is not a place where an architecture like this happens to land by chance, out of a tender that it might not have won and ended up elsewhere. The key in Hungary is its (seismic) geopolitics: historic, territorial, never quite in the same place and ever under harsh sieges, both from the East and West, but also from within. Sándor Márai did not want foreigners to know about this, about the mutual accusations between Hungarians, therefore refusing to have the first two chapters of his Confessions of a Bourgeois (1949) published abroad, at least until 1971, naturally under the title Earth, Earth!

Fujimoto’s unruly architectural proposal slid in at a time when ultraconservative political bases were settling in the country. This led to a sense of enthusiasm for bravery, thwarted only by the speed at which it was embraced by the authoritarian political class mindless of what citizens might want, relating the cultural project of Liget Budapest (with winning proposals also by Sanaa, Napur Architects, and participants such as BIG, Snøhetta…) to the splendour of the Hapsburgs and as a liberation from the decadence of Western culture (Novak, 2022).

If I had to generate an image to make people understand the delicate moment in which the architectural composition is internally debated, I would propose which is shown in figure 2.

And I would say, as an explanation that: this involves using the perspective sense of composition through Brunelleschi’s viewing device, with the famous mirror and painting, perforated with a focal, central keyhole. This central, formal, classic point of view, recreated in the diagram [2] with dotted lines, is tensed by current, reflexive components. In other words, it features Venice on the one hand for the left eye, reconstructing the heritage of its Campanile, though seen from the standpoint of the horse replicas stolen from Byzantium – just as Saint Mark was stolen, incidentally. Venice is important for it was the centre of the Universe (the Western universe, but the universe nonetheless).

On the other hand, it unfolds to reveal New York for the right eye, as recounted by Koolhaas, drawing a symmetrisation – not with the left eye, but with itself –, a matter which can be perceived in the work of Diller & Scofidio for the Philharmonic, reflecting on the pond with the verticality of well-defined laws. So well-defined, for instance, that the Central Park Tower (225 West 57th St) rising in the background follows traditional «admissible» compositive standards. It is important to highlight the internal debate in the evolution of skyscrapers as a composition on the NYC skyline (another Western universe, but the most universe in the contemporary pluriverse) since the Herzog & de Meuron appartments were built (56 Leonard Street NYC, 2006-2017), towering like a bastard in the urban grid (especially, needless to say, when seen from Billionaires’ Row). The reflection proves eloquent because Diller & Scofidio put a pond there (horizontally, of course) but on a slightly tilted, imperceptible podium which solidifies the water and makes it alien to gravity (and to the gravity of the compositive issue). With it all, once we admit that we are cross-eyed, from right to left, composition is faced with a dilemma when the cloud (/cloud/, as Rosalind Krauss would say in 1994, resignifying) of Fujimoto’s Magyar House of Music does not comply with what modern and classical traditions expect of it.

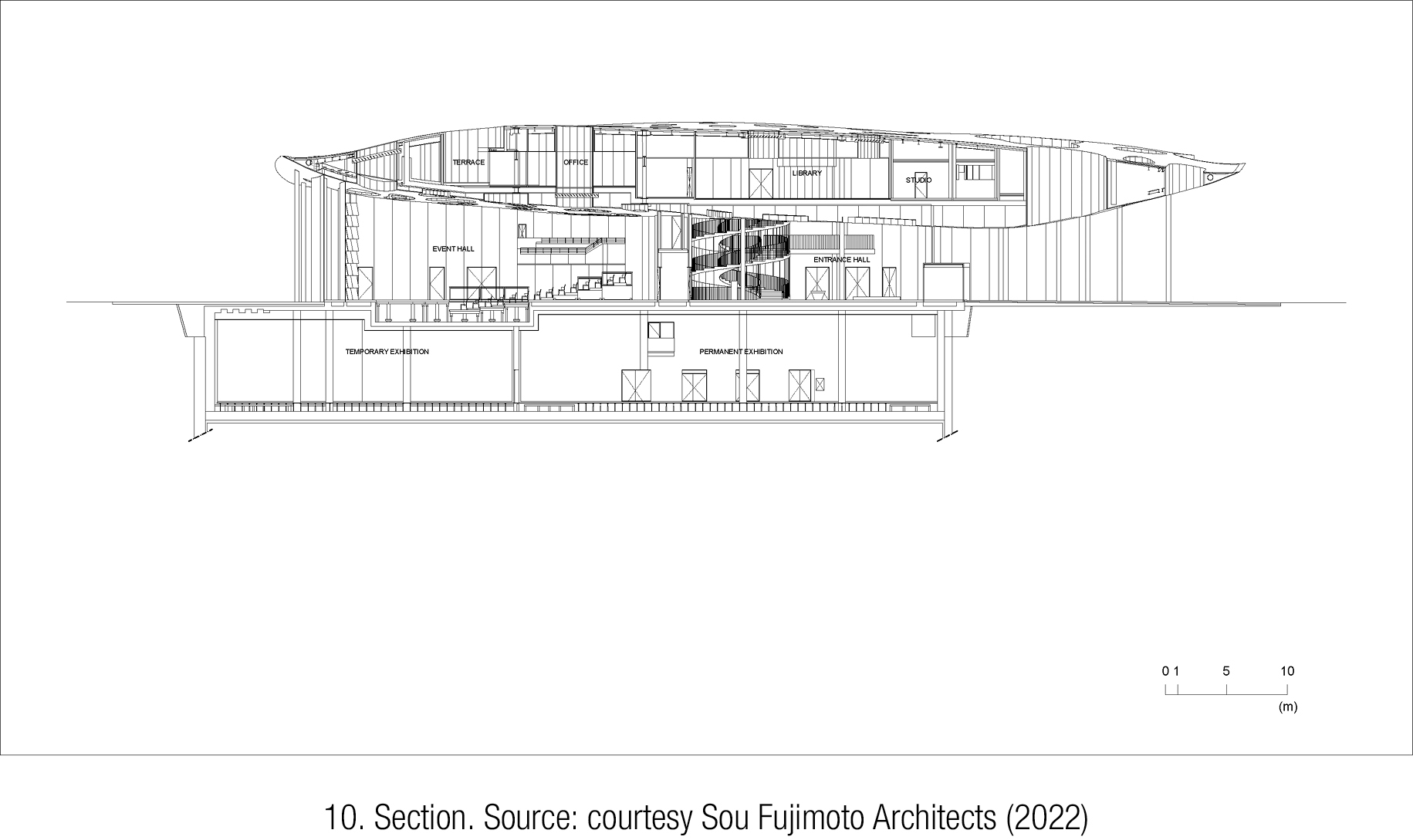

Moneo did not allow for anything like this on his path to the cubes of light of the Kursaal in San Sebastián in 1999, where disrupting the urban plan is precisely what the Spanish architect had planned as his compositive approach. With Fujimoto, the fact that it was built in a park would seem to justify the shape of the composition with the tree pits winding through the woods and with the very morphobiology of that urban negative. We have seen Koolhaas dishing out lectures on negative perfectibility according to the theory he explains to his son on the steps of the Laurentian Library: everything is composed wrong. His mythical metaphors, however, do not emerge from an association on the cortical surface, but somewhere much further down. Or we could relate this roof floating upon pilotis to the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (1968) by Mies with the Hungarian House of Music. If there is no formal recognition, despite both buildings presenting a mass raised upon supports and an underground volume of programme development in an exceptional area in the urban fabric, either in a park or on a block dedicated to the arts, it is not of the slightest interest and certainly not productive to engender this mere association for its legitimation. What would be interesting would be to recall that both works are immersed in the space and time of their beholder, that keyhole, and yet both display a resistance to meaning that calls pre-existing cultural values into question.

On a different note, it could be argued that art already took invasive stances and they were accepted in architectural action, and that just as art does not have to be justified, does not need to belong to a time, does not abide by rules or laws, neither does the architecture that arises from transfers of art. I wonder how much we would be willing to alter the Statute of Architecture, whether the time has come to rewrite its constitution, or if we should take liberties knowing that it is ephemeral, a passing phase. In any case, architecture journeys through its extraterritoriality – we said this at the beginning –, along the outer walls of its paradise, in the moorsof its orthodoxy. There are those who would be scandalised by this, while there are others who, out of ignorance, have no care for timelines – which is not the purpose of history –, who run parallel to the present, using this expression to convey a projectual key described repeatedly by Fujimoto himself. Therefore, somewhere between the Italian architects of the Venetian square and the Americans in New York, the author of the House of Music in Hungary accepts the compositive and disciplinary challenge, and rises to it with flying colours.

But Fujimoto is not playing the revolutionary, but rather the excited, self-taught discoverer. Nor is he playing the part-time joker (whoever sees a tell-tale extravagance is wrong), but rather – if I may continue to use these somewhat rude expressions – the self-exploited freelance (referring to his lack of genealogical ascription in Japanese architecture, to his formal architectural research and, as a play on words, to being his own employer who spends all of his time and more completing a roadmap that he has demandingly set himself since he was a student). If anything, he skilfully lends himself to fuelling pathologicals who have a syndrome of excess pareidolia – a donation of significant and gripping form, remember –, like a minor concession to succeed in bringing to life an architecture with more vocation, engagement, implementation. Hinting on a story spurs the achievement of more refined aims; such is the virtue of the myth. Or of apophthegms: «Everything is form, and life itself is form», said Focillon quoting Balzac in «one of his political treatises». And a pleiad of architects heard Focillon’s condescending and authorising call. Armoured by the book The Life of Forms and Praise of Hand, they felt free rein to quote the maxim. The quote is most probably not word for word, but taken from Lost Illusions (1836-1843: 819), where form is hypocritical social appearance. A weak argument inserted in a multitude of architectural texts that crack in the light of their referential accuracy, complex and hard to locate owing to the many re-writings, partial publications and compilations, or due to the translations of Balzac’s work which Focillon never clarified. That is why I posit that architecture is crucial in the constitution of societies; its depth demands an appropriate culture and any frivolity has very grave consequences.

Fujimoto operates somewhere between intuition and theorisation, so leading viewers to perceive a bolstered fragility is part of what he does. Allowing things to crack in order to show where tensions emerge, to become stable without restoring them to a pristine state, yet without delight owing to the ruinous nature of time standing still and with no other symbolic characterisation, only to find roots in the prototypical memory of «a landscape coming from the future» (Cecilia and Levene, 2010). If there is ruin it is because of the way Walter Benjamin characterised the image, backed by Derrida, constituting no referential index whatsoever, alluding to no single or original temporality. More than anything, it is a Lapsus Imaginis, as written by Eduardo Cadava, «Ruin, the image of ruin, is therefore imageless. It can never be presented» (Cadava 2001, 43). Borges, deprived of images by his blindness and photographed in 1978 by Daniel Mordzinski, recited it by heart saying, «Eres nube. Eres mar, eres olvido. Eres también aquello que has perdido […] ¿Qué son las nubes? ¿Una arquitectura del azar?»1 (Nubes 1. Los Conjurados, 1985).

The hypothesis I am presenting here concerning the immediacy of associating a given form with something recognisable, identifiable, psychoanalytical, mythical and not least metaphorical is not intended to be evocative, circumstantial or appropriative, but rather reductive, equivocal and incapable in the context of a prototypical future landscape. That context frames the author’s research and theoretical presupposition, consciously and in agreement with the most precise diagnoses and actions for our contemporaneity. Even if there were no such conscience, still the work could bear witness to its belonging to present times. Nevertheless, the fact that this work is admirable through action rather than justification is thanks to the broad destiny of architecture as a Field of Knowledge, not just when applied on the back of other gradually transdisciplinary fields such as philosophy, geography, politics or physics. In fact, quantum physics seduced our architect early on. Dealing with the odds of becoming a work based on bundles of information switching from one state to another and evincing the behaviour of complex systems is all part of what we see in the Japanese architect’s work: interiors that lean towards exteriority (House N), superimposed space-time (House NA), multiple planes on incompatible scales (Atelier House), hyperplasia of elementary particles (L’Arbre Blanc residential tower, Montpellier) and more. Metaphors? Without doubt, poeticization consists in critically employing translinguistic techniques to exit the common and enter something completely new. Hence why we had risked placing Fujimoto’s building in-between Classicity and Modernity. There are no recognisable forms here, only symptoms that architecture can take care of, both to give itself thought and to insert itself in its surroundings, which is what we had defined as the most conventional application of the myth. Indeed, myths have two faces, dispensing conceptual structure on the one hand and perceptual structure on the other. A good example would be the tender project to build the Cultural Centre of the Seven Twin Ports in Osaka presented by Lacaton and Vassal, where a cloud is permanently strutted to the building using cables. Fujimoto has also insisted on this percept, for instance in his Energy Forest in 2018 or the Flowing Cloud Pavilion in Tonglu, China, in 2022. There are disperse symptoms that diagnose processes which long for comprehension, a matter only attainable by the way architects work.

Generating conceptual frameworks is one of the constant awareness checks found in the architect Hokkaidō’s projectual exercise. Meanwhile, Walter Benjamin recircles one of his frameworks: He would say that any image is an image of the future, of possible pasts, futures, never entirely in existence. Therefore, in «Primitive Future» (2G, 2009: 137), Fujimoto speaks of clouds when describing the elements that compose his architecture, all potency, no act. It houses imprecise objects that, without contradiction, can be clear whilst maintaining their vagueness. If there is a cloud, it is because it is an abstract cloud and not a mental anamorphosis.

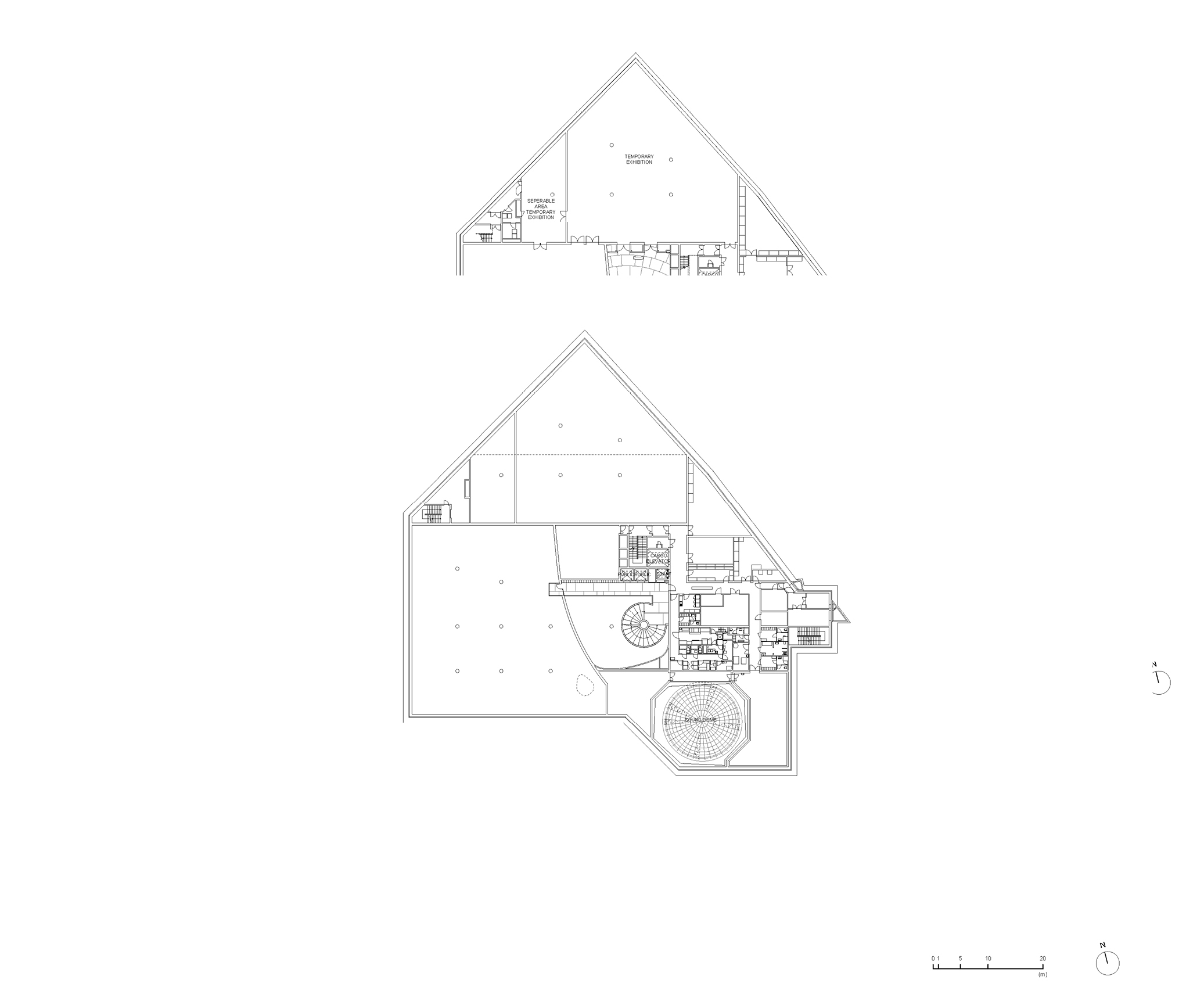

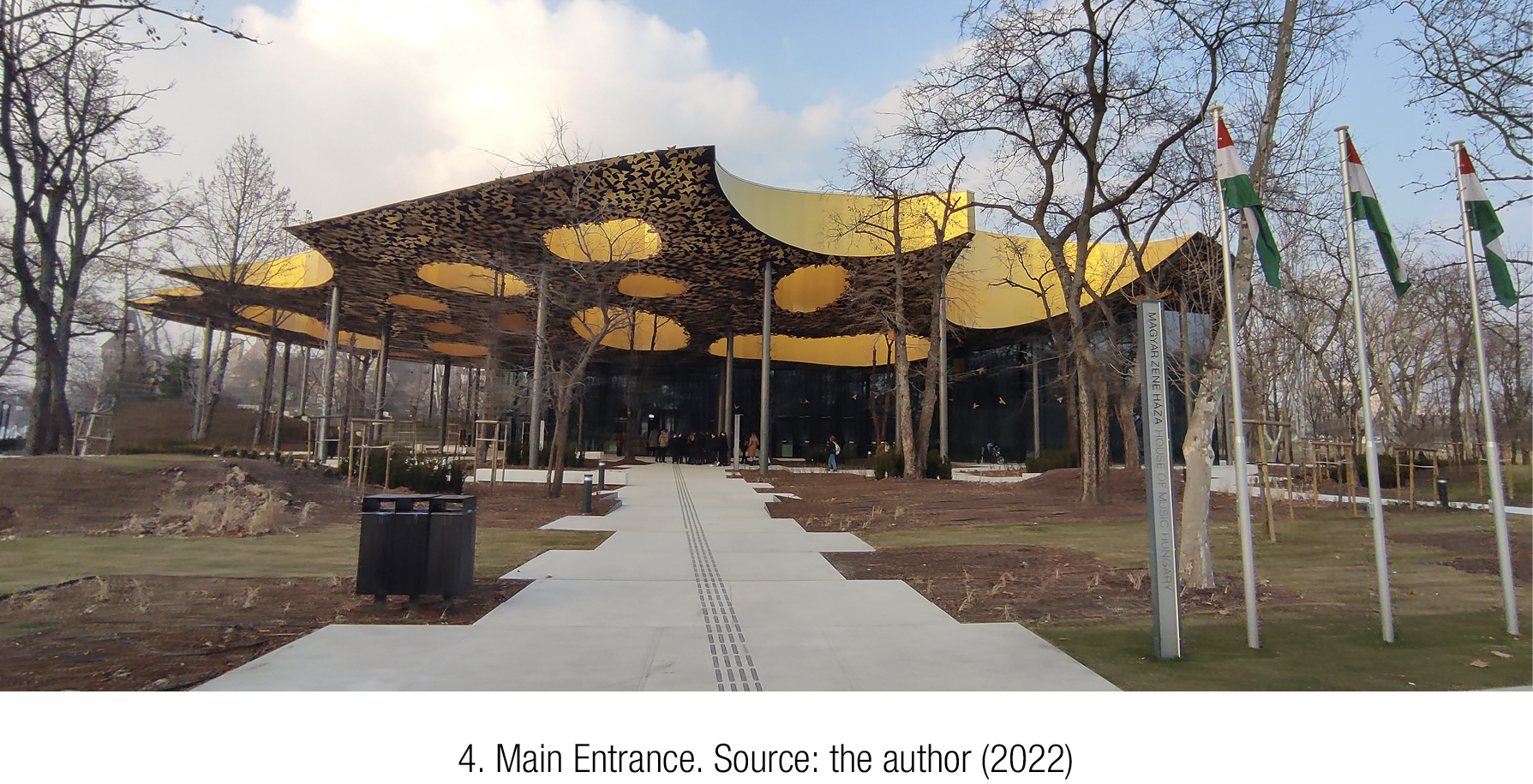

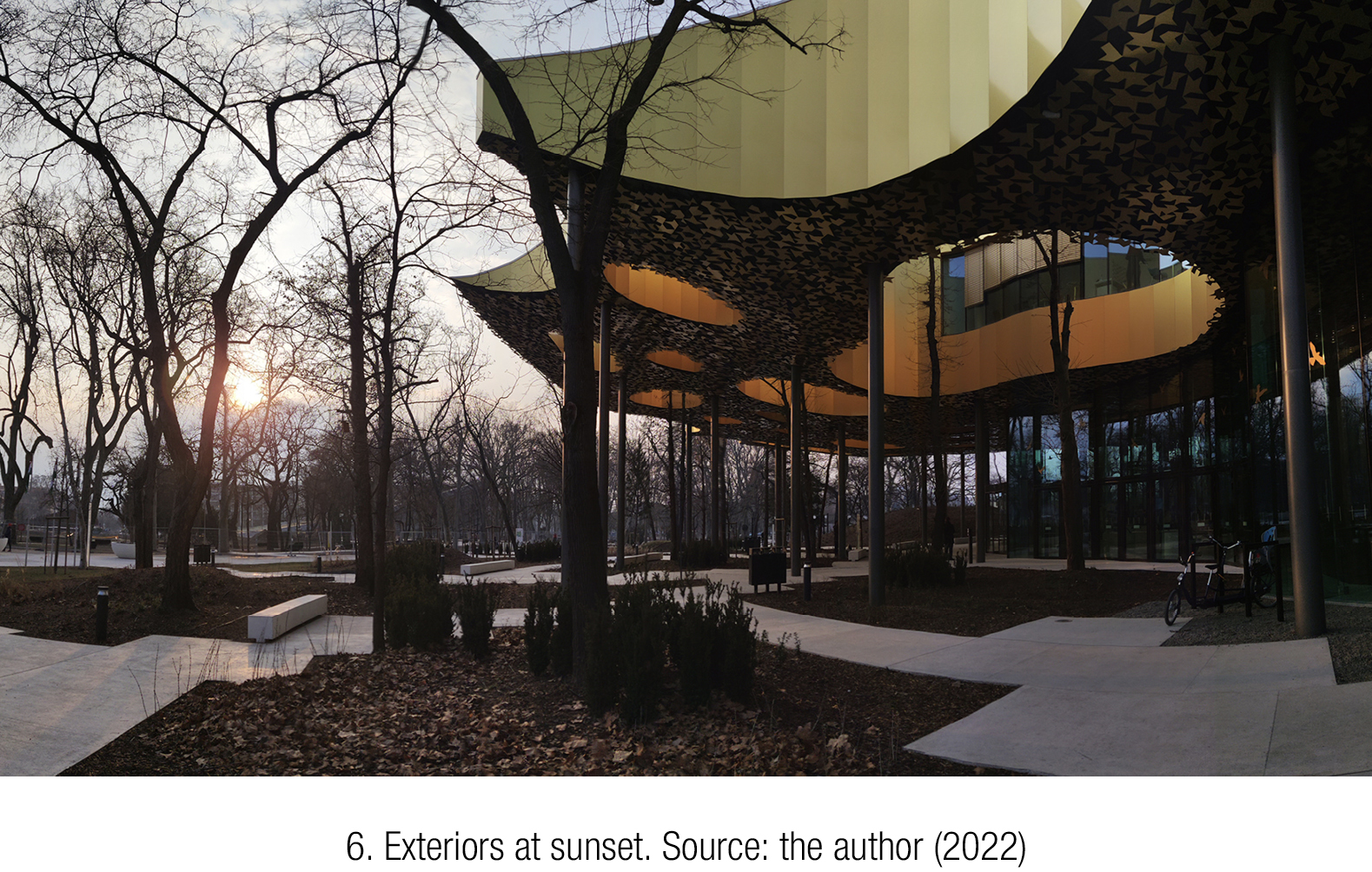

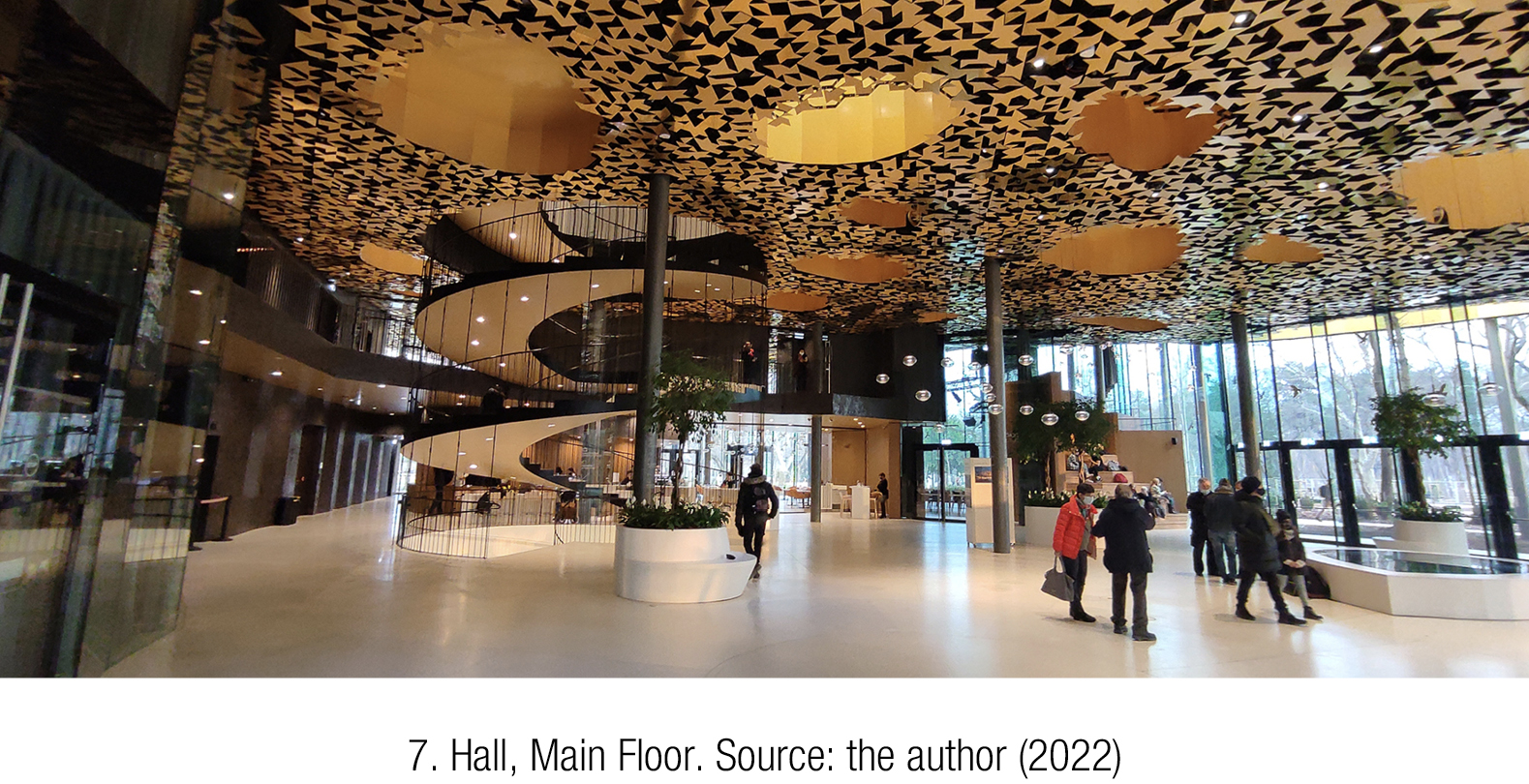

The building can be reached by public transport. You can choose either the generosity of the bus drivers, who are not supposed to dispense tickets but tend to take pity on foreigners without a pass, or the underground, where passengers pay according to the number of stops and ticket inspectors are ruthless if they travel so much as one further. Just like in Greece, where transport is called Μεταφορά (metaphor), both options are a sort of preparatory state for when disembarkation comes. Yellow line 4 if the underground is particularly interesting in terms of seeing what can be done architecturally in those cave-like spaces. And a bus ride through the streets of Budapest is simply magical. Andrássy út, for instance, boasts a disquieting beauty. Journeying down the less dense part of the urban layout to reach the park along Herminia út reveals the architecture of the Széchenyi Baths, built in 1913, or Vajdahunyad Castle, from 1908. The branches of the surrounding deciduous forest echo the sounds emanating from the House of Music. Heading towards the building, you seem to hear several of Béla Bartók’s bagatelles overlapping and look around for the musicians. Surprisingly, however, those rhythmic, monochord sounds are not ringing from pianos or recordings, but from the playground that the site could not be without. Children bouncing on musical cushions compose a decomposition that prepares visitors for their arrival. Huge panes of glass towering 14 metres high are set into the ground, almost to the bone but not quite, rising against the golden lattice made up of 30,000 pieces in the fashion of an endless tangram. The finishes fail to conceal a certain coarseness in the links and fastenings. Having seen the project submitted to tender, which was so much more stylized, lightweight and labile, held up by supports that missed the eye, the actual construction is a lesser version. The explanation lies in the client pressuring for it to be earthlier than vaporous. As a result, the densities in the hollows are lined with golden aluminium sheets, and the sinuosities become curvatures represented as though in a lower digital resolution.

Arriving after nightfall, which in February happens around 5 pm, that dark Shakespearean vesper envelops the building. That is the time when the pictures shown here were taken. One never arrives as depicted in the photographs in the magazines, adamant that all of us are or own drones. The game of perspective is grandiloquent because it is multifocal. Only that way can the slight curves of the bites in the levitating volume become unnerving incoherent teeth marks. To see it all, you have to stand back and, in doing so, the tension eases. Perfectly improvised paths paved with misaligned slabs locking in immaculate, level flower beds await a less gloomy eve.

A tangential glance. The glass is refractory, though not for the birds whose replicas are displayed on the panes to prevent them from colliding. A green iridescence with layers built up into thicknesses that ought to be painted like a Parisian Beaux Artspoché indicates how sound is enclosed and noise is kept out, compressing the air. Only this way can the idea of omitting pillars be carried through to the built version as well: tangential to the stands outside, tangential to the volume of the facilities opposite the restaurant entrance. The Ethnography Museum distracts the eye momentarily. It is no surprise, yet it is all surprising: a giant, semi-underground curve section, a roof that is a plaza seeking to strike more stable balances despite the fact that everything here is tense, like an indecisive archer.

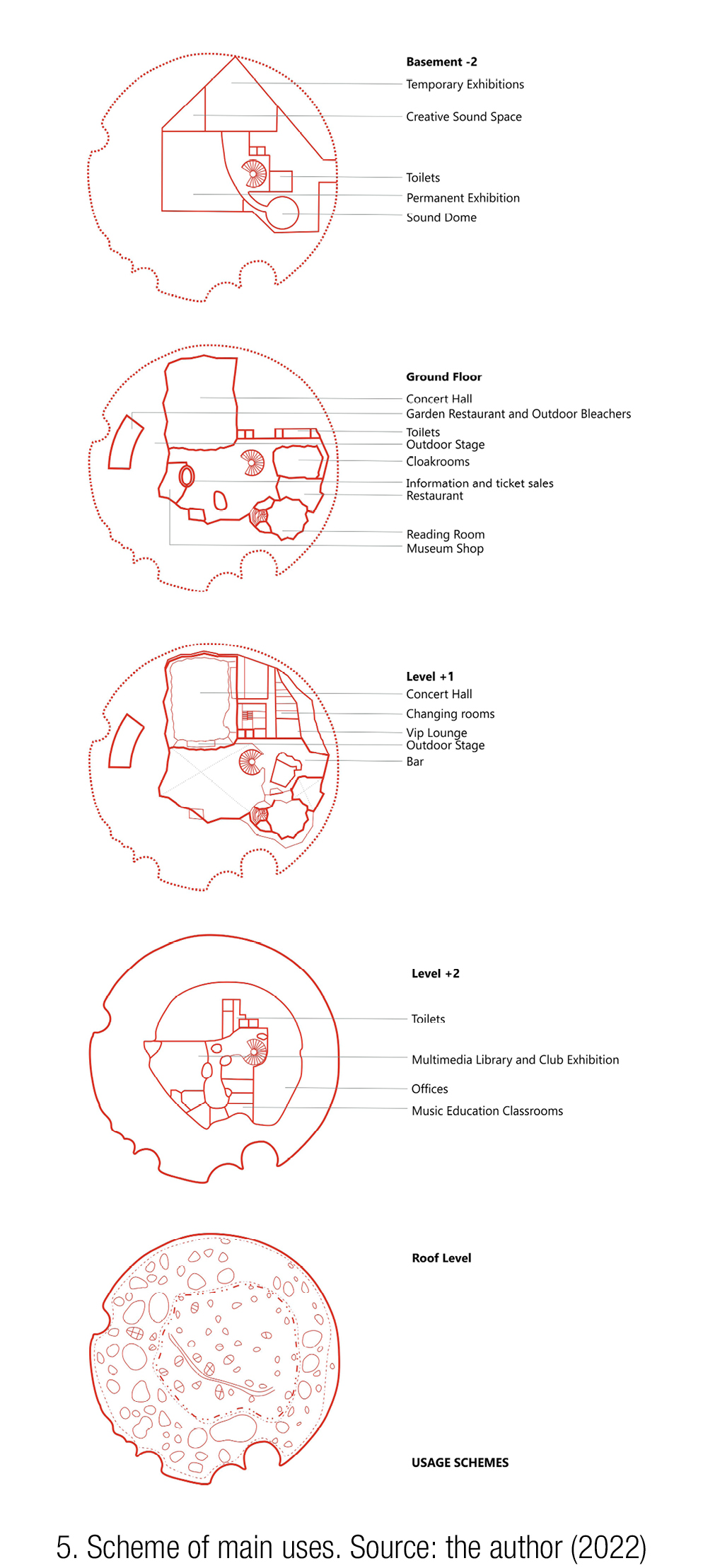

Back inside the House, 9000 usable m2 await us. As to whether there is a southern-European-style hallway in the Hungarian House, I doubt it. But there is something resembling a transition into the House, a change of mood as one walks through a bubble, lower than the outer panes but sharing the diagonal lines that become compulsory from that point on in the spatial immersion. Inside the atrium, nothing is composed. Nor is its decomposition instantly revealed. The most significant decomposition can only be observed once we reach the first floor after climbing an implausible spiral staircase. The triangular tread so typical of these stairs limits the proportion of legs that can climb them at any one time, aggravated by very low risers that force the climber to take tiny steps, like Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein would have done on the rare occasions she had to walk up to her husband’s chambers.

Fujimoto has explained it sometime: A short-circuited staircase elicits a reconsideration of the laws of the body. But this staircase is screwed from the atrium upwards with a show of ironwork and panes of glass, offering a completely different picture to the downward flight to the underground floors, where it becomes carved, white and solid. It appears as though, with every twist down, the matter unearthed adheres to the tunnelling machine. Aerial weightlessness versus abysmal density – an expressive literality through excess.

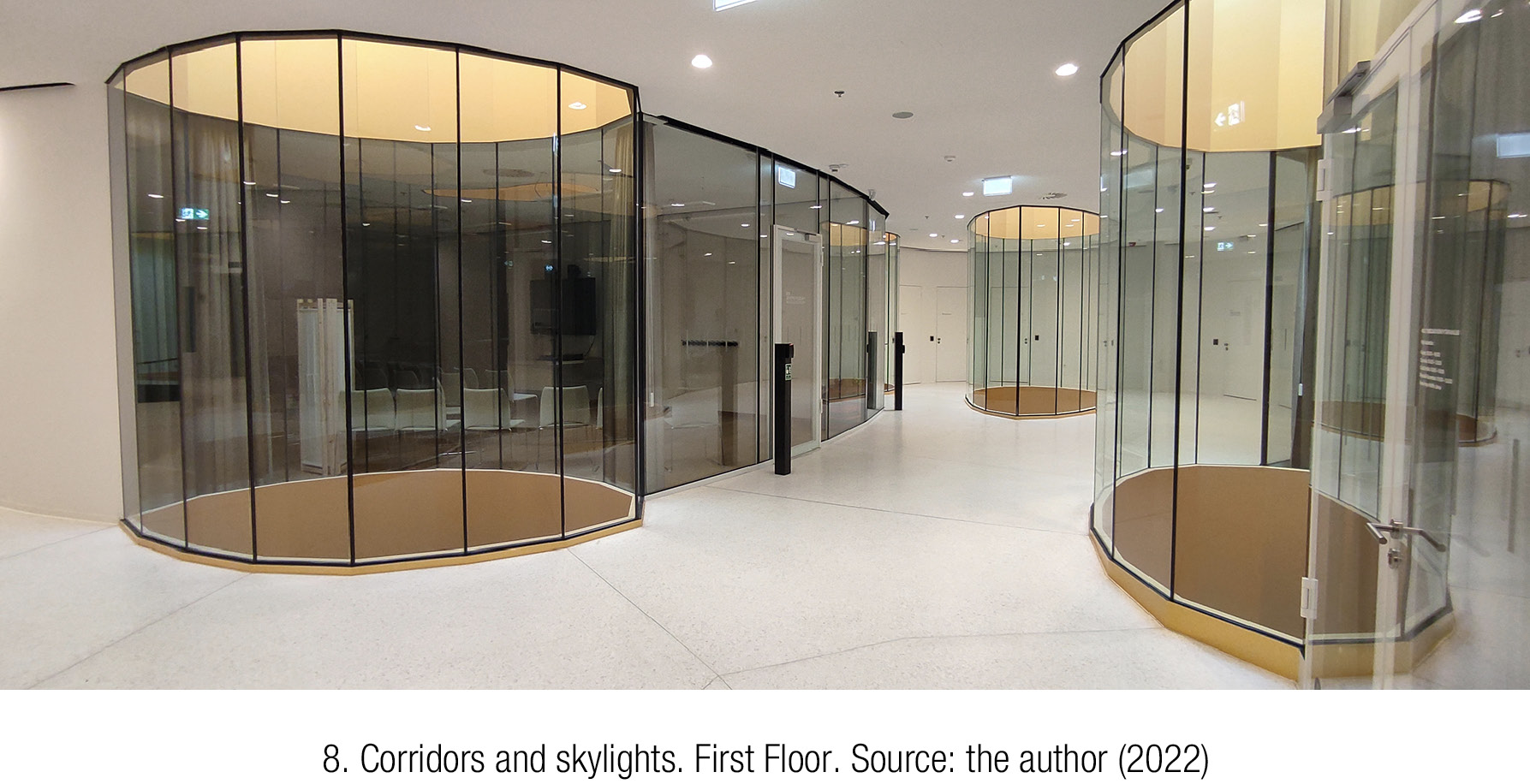

The spaces connecting the rooms, the skylights, the stairs, the access to the restaurant, bar and patio are so clean it is masterful. It is hard to comprehend why the convergences between vertical elements and sloping floors have not been resolved more successfully. There is a determination that everything should reach the ground that does not seem to have convinced the installer, who has dodged the challenge to make some very coarse finishes. These are things you learn from works.

What remains to be described is the view on the way up to the first floor, facing the atrium. An off-centre circle on the seamless paving from which new circles emanate in disparate parallels leads you to think it is there that the staircase should have risen, if the auditorium with its 300 seats had not prevented it. Therefore, we have two centres that are decentred, like everything sought here with Brunelleschian focality.

Deeper down, experimental halls for modern music stand beside temporary and permanent collections dedicated to 2000 years of Hungarian music. An immense remote building that deserves to be called nothing other than what it is.

When Miralles first had an issue of El Croquis dedicated to him, his interpreters did not understand. They were critics, not interpreters. And like all critics, their method is to set the new against the accepted. Thus, it was deduced that his forms were acceptable, but as there were no precedents, he was assured of genealogy: a mixture between Le Corbusier and Gaudí, between Orthodox Modernity and Christian Paradise, as we have already said. It is crucial to be trained in architecture, to avoid talking and saying nothing.

Better to be Eros than Antony, who takes away a degree of authority with every metaphor: «Ay, noble lord / Ay, my lord / It does, my lord… / Ay… /» silence, let the work speak.