In practice, the stake in all neo-liberal analysis is the replacement every time of homo economicus as a partner of exchange with homo economicus as entrepreneur of himself, being for himself his own capital, being for himself his own producer, being for himself the source of [his] earnings.

Foucault, 2008: 226

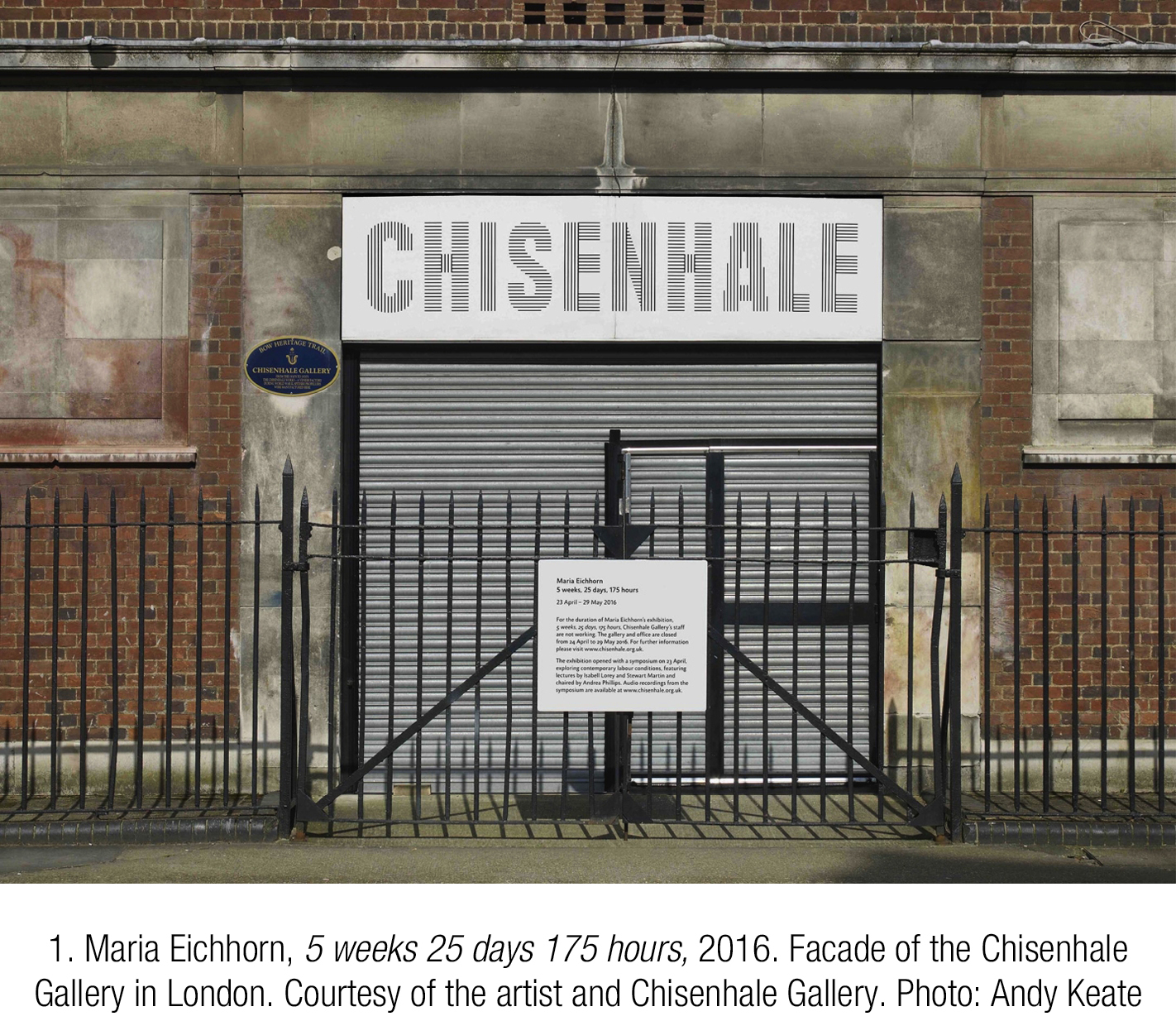

For her 2016 piece 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, Maria Eichhorn requested all Chisenhale Gallery’s staff to withdraw their labor in the institution for the duration of the show [1]. The gallery and its office remained closed for 5 weeks, during which Chisenhale’s employees stopped working: they did not have to commute to their workplace and all the messages received in their institutional email accounts would be automatically destroyed. At the artist’s request, they were sent on vacation for five weeks. The only tangible elements of the exhibition were a small notice attached to the gallery door explaining the reasons for the closure [2], and a discussion with the workers carried out by Eichhorn that was later published on the digital exhibition catalog1. The action was accompanied by a symposium where Isabell Lorey and Stewart Martin reflected with the artist and the audience on the idea of labor. According to the artist, the show was «a way of giving back time to the staff who work there» and her intention was to «interrogate the possibility of suspending the capitalist logic surrounding the notion of exchange and to try to make a space in life sans labor a reality, by returning time for those who lack it, or who need it» (Eichhorn, 2017: 224).

Eichhorn’s proposal is exemplary of post-conceptualist artistic practices that have aimed to provide a critical reexamination of the new imaginaries of work that emerged in the post-industrial context. The radical nature of this intervention not only presents itself as a negation of the artwork and the gallery space for beholders, artists, and cultural workers. It also presents a series of investigations into the concept of work and creative laborers’ subjectivities in the 2000s. 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours is framed in a form of radical conceptual practice that confronts the subject of work with a refusal. Eichhorn’s work revolves around the figure of the art worker in order to propose the withdrawal of labor as a form of radical resistance. This strategy is especially pressing since, following the financial crisis of 2008, «precariousness, precarity and precarization have already become a novel territory for thinking about – and intervening in – work and life» (Gill and Pratt, 2008: 4). Eichhorn’s work is inscribed in this framework. Fundamentally grounded in the intervention and mining of art’s socio-legal constructs, Eichhorn has developed her practice by following the legacy of Institutional Critique since the 1980s. In what follows, I explore how her work fits into the tradition of Institutional Critique, and then I focus on the labor issues that the piece raises.

Over the last few years, the complexities of artistic work and the role of the artist in the post-industrial framework have been a recurring subject of study by theorists and critics. Anthologies focused on art, labor and the post-Fordist economy include E-flux’s book Are You Working too Much? Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor of Art, published in 2011, the title Work (2017), from the collection Documents of Contemporary Art by Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press, edited by Friederike Sigler, or the work of Gerald Raunig, Gene Ray & Ulf Wuggenig, more specifically their anthology Critique of Creativity: Precarity, Subjectivity, and Resistance in the Creative Industries (2011), which constitutes one of the first editorial projects that centered on shaping a solid critique of the debate on cultural industries and creativity in a contemporary context. In this paper, I draw on these lines of analysis, trying to give shape to a model of my own that allows to develop an analysis of the work and explore its political possibilities. Among the bibliography dedicated to 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, it is of specific importance the aforementioned intervention’s catalog, edited by Chisenhale Gallery, which includes a theoretical essay by Lorey that assesses the work in the light of her theory of precarization, and revolves around ideas of gift, debt, trust, and time. A more recent article, «Let me Sleep. Dreaming about Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours» published by Anahita Delcorde in Afterall in 2021, also constitutes an interesting review of the work in the times of Covid-19 and pays special attention to its impact on the public, the idea of artistic consumption, and the possibilities of resistance to labor that the piece opens up.

Yet in these works, some of the specific aspects of the post-Fordist context, such as the decisive role of technologies in the New Economy and the 24/7 temporality imposed by capitalism, have been somewhat overlooked. An important part of the present essay seeks to reconsider the effect of Eichhorn’s proposal by considering the new modes of capitalist exploitation in the digital environment. For that purpose, I draw from the work on Network Culture and digital free labor by Tizziana Terranova. Likewise, I approach ideas of time and space within the theoretical framework of authors from Italian operaismo and autonomism, such as Maurizio Lazzarato, Paolo Virno, or Antonio Negri. It is my intention to propose a more thorough analysis of the piece in terms of the economic and socio-political specificities of the contemporary art field, and, by extension, of the new conception of labor in today’s hyperconnected world.

I read in 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours a figuration of the new worker of the neoliberal context. I also see in the piece an imaginary of the structures of self-government typical of immaterial labor, as well as of an increasingly conflictive conception of space and time. As a consequence of the development of new modes of production in late capitalism, work (or rather, productivity) pervades every aspect of life, complicating the idea of free time and sentencing workers to perpetual productivity. Finally, I consider whether Eichhorn’s work fulfills its purpose of resistance to work, focusing on her reflection on the economic and social systems that condition labor in the art world today. Ultimately, the present paper is rooted in a profound concern for the current increasing precarization of labor in the arts, and the commitment to find possible alternatives in the field of art itself.

A Radical Gesture: Closing the Gallery

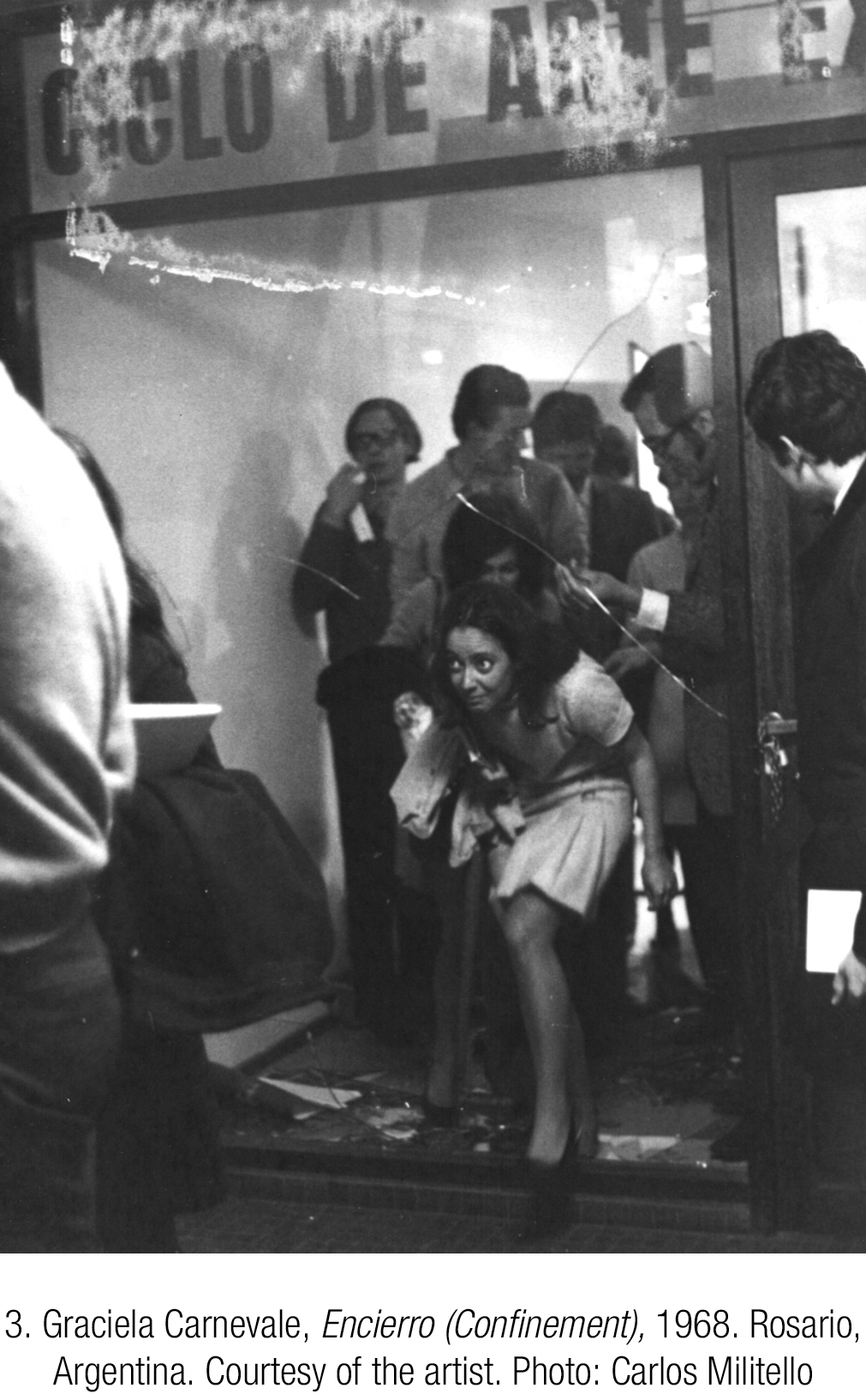

Eichhorn’s decision to close the gallery relates to a phenomenon highly developed in 20th-century art history that took the conceptual gesture of negation as a creative expression. One of the first manifestations of this kind was Daniel Buren’s first solo show in 1968, in which he closed the Apollinaire Gallery in Milan covering its door with a white and green striped wallpaper. Buren’s work implied «the absolute non-necessity of the gallery’s interior walls, the self-evidence of a work’s presence, and its inaccessibility to property» (Copeland and Lovay, 2017: 83). In this same year, in Rosario, Argentina, as part of the Ciclo de Arte Experimental (Experimental Art Cycle), two artists would perform similarly radical interventions. In his Galería Privada (Closed Gallery Piece), Eduardo Favario shut down the gallery where his solo show should have been held, and put up a sign inviting the visitors to walk to the new location for his exhibition. At the same art event, unaware visitors were locked up in a gallery for Graciela Carnevale’s Encierro (Confinement), and were only released when a passer-by broke the gallery window [3]. As with Buren’s work, these last two interventions aimed to expose the problems and contradictions of the institution of art. In the case of Carnevale, it also drew attention to Argentina’s political repression, alluding to «the power with which violence is enacted in everyday life» (Carnevale, 2011: 76). Following a similar impulse, in 1969, Robert Barry attacked the gallery system by announcing that during his three solo exhibitions – held in Amsterdam, Turin, and Los Angeles – «the gallery would be closed»2.

Conceptual works like the ones mentioned, which were marked by a notion of dematerialization, sought to resist the marketability or institutionalization of the artwork. As Sabeth Buchmann has suggested, these efforts contributed «the idea that instead of being measurable only in terms of the fact of material production, the form of art’s symbolic value should be equally open to calibration using scales of social productivity» (Buchmann, 2006: 179). The post-conceptual movements of the 1980s and 1990s inherited this logic, which was accentuated by the rise of immaterial labor and cognitive capitalism in the last decades. Eichhorn’s practice is situated within these approaches that recuperated some of the forms of the 1960s and 1970s conceptual art, now permeated by critical discourses around post-Fordism, the new service economy, and neoliberalism. Likewise, many of these practices, situated within the legacy of Institutional Critique, stemmed from the urgency of restoring the public sphere and political invention within the institutional context (Alberro, 2016).

The gesture of closing the gallery resurfaced during the 2000s, this time as an explicit statement against the neoliberal discourse. Such is the case of Santiago Sierra’s intervention at Lisson Gallery, Space closed by corrugated metal (2002), in which the artist placed a metal shutter to block the entrance, or Rikrit Tiravanija’s show at Toronto’s OCAD in 2007, in which a brick wall with the Situationist slogan «Ne travaillez jamais» obstructed the gallery’s entry. Eichhorn’s 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours follows this same pattern, but her gesture is not solely centered on the denial of the artistic object or the role of the artist as producer. Rather, I would argue that the act of negation in Eichhorn’s work takes a secondary position. In the statement released upon the inauguration, the artist insisted that the staff abandon their jobs and enjoy their free time as the fundamental axis of the piece: «That the exhibition space and gallery offices are closed is just a spatial consequence of this gesture. […] The institution itself and the actual exhibition are not closed, but rather displaced into the public sphere and society» (2016). In this sense, by closing the gallery, her intervention renders visible a work that usually remains invisible, that of the gallery staff, and, at the same time, opens up a discussion on the institutional and social aspects of creative labor, as well as the position of the artist in relation to them.

However, to interpret 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours exclusively as a boycott or a «strike» wouldn’t be exactly accurate, since the non-activity of the employees does not respond to a movement of resistance but to a request from the artist, or, as she described it, «a gift». In fact, regarding a possible interpretation of the piece as a strike, Eichhorn made the following statement in the exhibition catalog:

When a passer-by comes by the closed door of Chisenhale Gallery and reads the sign on the fence, it could occur to them that a strike is taking place here. But this strike is not chosen, rather, I have imposed it. Strikes are mostly held for higher wages and better working conditions. Why is there a strike here? The Chisenhale staff have every reason to strike; maybe not due to low wages, but due to the lacking support of the public authorities. This is how art is privatised and disappears into the arsenals of the sponsors and the rich (2016: 63).

With respect to the notion of «gift», Eichhorn’s conceptual work often involves gestures that reveal and question systems of power and value, drawing attention to the contradictory and speculative dynamics within the institutional sphere of art and the capitalist system. Very frequently, her practice entails some sort of service provision. Alter and Alberro have elaborated on this component of her work, noting the parallel between the artist’s idea of the gift and what Jacques Derrida identifies as the ideal state, «for which the giver remains anonymous, requiring neither gratitude nor recognition, and does not receive any benefits» (2017: 95). Some examples of this tendency are her work Das Geld der Kunsthalle Bern / Money at Kunsthalle Bern (2001) in which the artist devoted her exhibition budget to restore the building of the Kunsthalle, or her 1992 exhibition at Künstlerhaus in Stuttgart, for which the artist donated painting and drawing materials to be used in workshops with groups of school children.

On many occasions, the service provided by Eichhorn is not easily perceived at first sight. Instead, it constitutes an intellectual proposal, offering certain information that normally remains hidden. Such is the case with her intervention for Documenta 11 in 2002, for which the artist invested a capital of 50,000 euros to fund a public limited company in her name, Maria Eichhorn Aktiengesellschaft [4]. She then divided it into 50,000 shares of one euro each. Yet, unlike most corporations, the assets of Eichhorns’ company were not supposed to be part of the macro-economic circulation or produce surplus value and contribute to the accumulation of capital. They were all to be transferred to the company itself, and in this way, the company would belong to itself, or in the artist’s words «it ultimately belongs to no one» (Eichhorn, 2011: 387). With this work, Eichhorn drew attention to the hidden money flows moved by companies, and, by appropriating the very logic of stock market finance, defeated the fiction that money is self-generating (Ferrel, 2006:196).

5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours operates in a similar manner, using a radical gesture to raise questions about ideas normally taken for granted. By closing the gallery and giving the workers the gift of free time, Eichhorn invites a reflection on contemporary working conditions and the very notion of work itself. She wonders «what work means, why work is synonymous with production, and if work can also consist of doing nothing» (Eichhorn, 2016). As such, what 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours offers is not only the gift of free time to the workers of the Chisenhale gallery, but also a valuable reflection on the transformations of the notion of labor under the post-Fordist system. This public dimension of the work is materialized in the documentation of Eichhorn’s interviews with the creative workers, in the ideas she elaborated to organize the symposium, and in the visitors’ reactions upon encountering the closed gallery [5]. In this regard, it is noteworthy to clarify that I am considering the notion of public art not as the kind of art that occupies a physical space outside the institution or the museum and intends to address a universal subject. Instead, I am referring to the notion of public art as proposed by the art historian Rosalyn Deutsche, who understands it as a practice that constitutes a public sphere by engaging people in political debate (1992). I argue that here the radical gesture of closing the gallery adds a further political reflection on labor that takes two directions: on the one hand, it presents the artist as the provider of a certain gift or service, and on the other, it invites the spectator to reconsider the parameters in which the idea of work is assumed, to realize how capitalism shapes one’s life through work, and, ultimately, to imagine a future without labor.

Flexible Personalities, Precarious Subjects

In a section of the interview that Eichhorn conducted with the Chisenhale Gallery staff as part of her intervention, one of the workers of the gallery, when asked about her job in fundraising, answered the following:

It takes up a lot of my working day, as well as personal time [emphasis added]. For example, when you go to an opening and you’re still representing the gallery. You can’t clock out and say, «I’m just going to chat». You’re always conscious of the fact that you’re working. You will often see people who are supporters of the gallery (2016: 33).

Pursuing the conversation, the director of the gallery noted that one of the particularities of working in the arts is the difficulty of separating their jobs from their private lives (Eichhorn, 2016: 33). The artist’s reaction was one of incredulity, then asking the staff if this invasion of work into private life was not difficult for them, to which the gallery director responded: «Yes, but I don’t mind that» (Eichhorn, 2016: 34). These statements illuminate on one of the most evident consequences of labor conditions in neoliberal economies: that work has come to occupy most of our time, it has infiltrated our private life, extending to our personal relationships, and contributing to the construction of our subjectivities. Moreover, the words expressed by the director, «I don’t mind that», denote another significant component of post-Fordist work: self-discipline, the internalization of control. In 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours, Eichhorn addresses these very considerations around labor, delving into the exploration of the figure of the post-Fordist creative worker: a precarious and hyper-connected subject.

The transition to a model of capitalism progressively based on immaterial labor and governed by information and communication technologies has led to a new type of worker engaged in increasingly insecure and precarious labor. Consequently, the issue of precarization has become one of the fundamental axes of the debate on labor in contemporary capitalism. Some authors speak of the précariat as the specific class of the post-Fordist economy, which includes those workers whose employment is never guaranteed, who live exposed to contingency, and in a constant state of insecurity. Yet the conceptualization of the precarious remains complex, as it comprises an extremely fragmented group of workers.

While the rise of immaterial labor and cognitive capitalism has certainly made precarization the norm, it would be wrong to assert that this is a recent phenomenon. As Angela Mitropoulos has argued, precarious work has always existed in the capitalist context, mostly encompassing care, affective, and sexual labor: those forms of work not widely recognized as such in society and which to a large extent affect women, migrants, and racialized workers (2012). In a similar vein, Silvia Federici has widely elaborated on women’s unpaid, reproductive, and care work as the basis of capitalism (2012). To identify the different dimensions of the recent shift towards insecurity, some have spoken of a rigidly repressive form of precarization, that which impacts migrants and the undocumented, and another type of precarization characteristic of the «creative class», which some refer to with the terms «intellos precaires» or «digital Boheme» (Raunig, 2007). I use the term «self-precarization» to address this latter form of insecurity, so that there is no doubt about the difference between those who do not have any option but to be exploited and those who agree to it voluntarily, enacting a sort of servitude volontaire.

Eichhorn’s conversation with the workers of the Chisenhale Gallery reveals how the phenomenon of self-precarization operates within the framework of contemporary art. By inviting the employees to discuss their conditions within the gallery, her work explores how the subjectivities of the individuals working for the art institution are configured in the new economic order in which intellectual and creative labor is integral to the process of production. Many authors have singled out art workers as the epitome of immaterial workers, since their activity consists of producing knowledge, ideas, or experiences, and is based mostly on connections and social relations. Indeed, creative and cultural workers easily parallel the model of the «opportunist worker» introduced by the theorist Paolo Virno: individuals whose survival depends on the skillful utilization of opportunities, «who confront a flow of ever-interchangeable possibilities, making themselves available to the greater number of these, yielding to the nearest one, and then quickly swerving from one to another» (2003). The art system is largely supported by freelancers, volunteers, unpaid interns, and, in general, precarious subjects. This phenomenon is related to the discourse on creativity exploited by neoliberal ideology, in which precarization is often masked behind the euphemisms of autonomy, flexibility, and freedom. Thus, one of the most tangible consequences of the reformulation of production systems towards immaterial labor in the field of art is self-precarization, a form of self-imposed precarization that functions as an instrument of self-governance, according to the concept of governmentality developed by Foucault3.

Drawing upon Foucault, Lorey elaborates on the concept of the precarious beyond its meaning of job insecurity. She argues that precarization, «by way of insecurity and danger…, embraces the whole of existence, the body, and the modes of subjectivation» (2015:1). It responds to a biopolitical articulation of a governmentality determined by the neoliberal economic and political framework, which implants on the individual the entrepreneurial-self as a dominant form of subjectivation.4 This new construction of subjectivity foments a belief in the control of the self and of one’s own precariousness, as well as an illusion of improvement of one’s life through the values of initiative, competitiveness, and flexibility. Thus, Chisenhale workers’ assumption that their work in the arts makes disconnection from labor impossible, and their acceptance of this condition as unavoidable, shows how work has been completely internalized and controlled by self-government. Their work for the gallery has come to determine their identities as individuals and their private interpersonal relationships. In this way, the gallery employee embodies the opportunist entrepreneurial-self, as she «has to perform her exploitable self in multiple social relations before the eyes of others» (Lorey, 2015: 32).

Relatedly, Virno brings attention to how «within the sphere of culture industry […] communicative activity which has itself as an end is a distinctive, central and necessary element» (2003: 56). Like other forms of immaterial labor, creative workers rely on managerial functions. They manage social relations and their own activities. The productivity of the gallery staff is to a large extent based on constant communication and networking. Their relational capacities become fundamental for their subsistence. Yet, paradoxically, this model of labor, which takes place in an increasingly online context and is permeated by a principle of extreme competitiveness, favors new forms of individualism. Post-Fordist labor relies on the establishment of opportunistic networks but generates increasingly isolated individuals, outlining a scenario that complicates collective political action. Philosopher and activist Brian Holmes describes this new subjectivation as a «flexible personality», which he identifies with a new form of alienation and social control, or «a distorted form of the artistic revolt against authoritarianism and standardization» (2001). Given the extended situation of precarity, Butler points out that «in the place of critique and resistance, populations are now defined by their need to be alleviated from insecurity, valorizing forms of police and state control» (2015). Indeed, there is a common tendency to resign to, rather than question, the neoliberal system of control: gallery workers have accepted that it is impossible to separate private life from work. Yet, following Foucault, new forms of dissent could be found in the practice of critique, since, within the state of governmentality, critique constitutes the art of voluntary insubordination (1997: 47). It is within this framework that Eichhorn’s intervention is situated.

In State of Insecurity, Lorey speaks of the possibilities of mobilization and resistance that exist in the current context of incipient normalization of precarization, anticipating the emergence of new disobedient forms of self-government of the precarious (2015). Along the lines of Butler’s thinking, Lorey proposes an activism that flees from victimization and finds its potential in the identification of oneself as precarious. Eichhorn’s work operates in a similar spirit. Her gesture calls for a rejection of the government of the precarious and the capitalization of life. It proposes an alternative that begins with the self-awareness of this precarization and challenges the extended subjugation of the neoliberal regime of power. Chisenhale workers’ acceptance of the omnipresence of labor in their lives and their extreme commitment to the institution speaks of the subtle coercion exercised systematically on immaterial workers. Eichhorn’s conversation with the staff makes strikingly apparent the naturalization of self-government, but also draws attention to the vulnerability of the public art system in many European countries, where private sponsorship has become the main source of support for arts institutions. The gallery’s employees have shaped their identities according to their work. In pursuit of donors and economic supporters, they have become the institution, embodying a paradigmatic example of the post-Fordist creative worker. By rewarding the staff with free time, Eichhorn opens up the possibility of a relief from this dynamic of perpetual production in the form of networking. Yet, in view of the technologies of self-government operating within the neoliberal model of labor, it is important to ask how this suspension of labor can be realized when work spans the workers’ entire lives, their social relationships, and their subjectivities.

How to Close the Workplace when it Doesn’t Have a Physical Dimension?

Eichhorn confronts the regimes of domination imposed by post-Fordist labor by closing the gallery and giving time back to the employees who work there. With this gesture, she reveals «that time does not belong to anyone and should somehow be re-evaluated, or even extricated from contemporary economies» (Eichhorn, 2017: 225). Her work deftly emphasizes the category of time to address our conception of labor. The piece’s title, 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours, indicates this:

5 weeks represent the total duration of the exhibition. This time representation refers to and includes both working time and free time […]. The time representation 25 days encompasses the working days affected by my exhibition. Because the staff do not work on the weekend, the Saturdays and Sundays (10 days in total) are excluded here. The representation 175 hours ultimately indicates the pure working time, wage labor. This amount of time refers concretely to the working time that has been transformed with the exhibition into non-work inside of work. The title therefore contains the thematically and formally relevant time representations involved in the exhibition (Eichhorn, 2016: 60).

The artist concludes that the artwork results from her «engagement with time in connection with current labor relations in society and in the cultural field». It consists of «giving time to the staff. Once the staff accepts the time, once work is suspended while staff members continue to receive pay, the artistic work can emerge» (Eichhorn, 2016: 60). As such, the artist equates the suspension of work with the absence of workers in the gallery. Her gift of «free time» is interpreted as a form of resistance or liberation from work.

Concepts of working space and working time have been altered in post-Fordism, which renders labor more autonomous. According to the theorist Sergio Bologna, the autonomization of work entails a transformation of the labor process by a spatial and temporal discontinuity: working time becomes porous since autonomous workers must have complete availability to work (1997). Simultaneously, the perception of space is affected by the de-structuring of the spatial organization of Fordism, traditionally represented by the factory or office. The idea of «workplace» is eroded by a set of modifications that complicate the distinction between private and work space (López-Álvarez, 2016: 682). In a similar vein, Lazzarato introduces the concept of «diffuse factory» to allude to this non-place where the cycle of production takes place under post-Fordism. The diffuse factory accounts for the decentralized work typical of post-Fordism: since surplus-value now derives from the control of financial and communication flows, «the cycle of production of immaterial labor is no longer defined by the four walls of a Factory» (Lazzarato, 1996: 136). Thus, labor ceases to be limited to a specific space and time and it becomes fluid, its temporality coincides with the time of life (Lazzarato, 2006: 37).

For the workers of the Chisenhale Gallery, whose subjectivities are crucial for the functioning of the institution, the workplace ceases to be limited to the gallery itself and extends to the totality of each worker’s existence. This prompts several pointed questions: Is the gesture of closing the gallery and sending the workers on vacation enough, given the bio-political feature of labor? Can time really be given now that a workday is no longer a unit of measure for work? How can one close the workplace if it is no longer limited to its physical dimension?

Subjectivities have become the center of economic exploitation in forms of immaterial labor, and with that communication and social relations have become crucial in order to produce surplus-value. Following Lazzarato, the production of subjectivity not only acts as an instrument of social control, but has also become directly productive, as «the goal of our postindustrial society is to construct the consumer/communicator — and to construct it as active» (1996: 142). In her relationships, the neoliberal subject, as an entrepreneur of herself, will always seek a productive end. Of particular interest here thus is reflecting on what Eichhorn’s gesture of sending the gallery’s employees on vacation implies in terms of sociality. As Lorey writes in the catalog of the work, «the capitalization of sociality also encompasses the countless places and networks that extend beyond the gallery space. The institution spreads in the socialities of those working within it» (2016: 44). In this way, it could be asserted that the workers liberated from labor by Eichhorn, even if they no longer answered their gallery email, remained productive. Their own subjectivities and relationships with others persisted in being capitalized. This idea is particularly noticeable when reading the testimony of the gallery workers who admitted that their personalities, social relationships, and friendships were determined by their jobs (Eichhorn, 2016: 34). Considering that another important condition of the rise of immaterial labor is its intrinsic link to the development of information technologies and the internet, the escape from perpetual productivity becomes even harder to achieve.

Indeed, the hyper-connectivity that characterizes today’s society and its permanent capitalization makes it harder to equate resistance to work with the physical absence of the laborer in the workplace –that is, the traditional strike. Now that the commodification of personal data has become the new engine for the production of wealth, it becomes impossible to address the issue of labor without taking into account the centrality of the digital economy –or the «New Economy»– in contemporary capitalism. Any reflection on modes of resistance or liberation from labor must consider the digital milieu and acknowledge that our post-industrial society is immersed in what theorist Tiziana Terranova refers to as «Network Culture»: a cultural formation characterized «by an unprecedented abundance of informational output and by an acceleration of informational dynamics» (2004:1). In the context of the Network Culture, mobile devices, computers and telecommunications function as technologies of governmentality for capitalism, emphasizing the biopolitical character of immaterial labor. Eichhorn’s proposal to re-evaluate time, or even remove it from contemporary economies, is further complicated by the omnipresence of information technologies in our lives. The new paradigm of the Network Culture not only evidences the phenomena explained previously, but also entails new forms of economic exploitation. Given these factors, concepts of «free-time» and «leisure» central to Eichhorn’s work 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours seem to lose their conventional meaning and validity.

Considering that the internet spaces of today’s hyperconnected world are already productive, one might question Eichhorn’s notion of a purely unproductive time. According to Negri and Hardt, the traditional distinction between productivity and unproductivity is defunct today (1994: 10). Even if Eichhorn acknowledges the 24/7 temporality imposed by the neoliberal notion of work and makes time the heart of her piece, her project situates itself in an aspiration of liberation from work where information technologies play no decisive role. Yet everything suggests that it’s precisely the digital that needs to be subject to in-depth inquiry if one wants to achieve –or at least try to achieve– that liberation. At a time when our mere presence on the Internet can be considered unwaged labor, the question we should ask is not if work can consist of «doing nothing», but whether there is a way to escape from the uninterrupted flow of information and social networks and resist bio-political control. Is an alternative digital scenario that would facilitate spaces for emancipation instead of exploitation possible?

…

Eichhorn’s work 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours constitutes an experiment that draws attention to normally overlooked conflicting aspects of labor, avoiding easy answers or immediate solutions. It illuminates important issues of the art world under neoliberalism as it compels us to realize the shift toward immaterial labor undergone by the art system in the last decades. The artist proposes a reflection on the social conventions imposed by the economic system, opening the horizon to different possibilities and perspectives. Her aim is not to denounce an exploitative situation of the institution’s laborers, nor to advocate for a better work-life balance in the gallery. Rather, her piece should be read as an attempt to challenge the post-Fordist idea of work within neoliberalism, and, more specifically, how work increasingly seems to be the main axis around which our lives are articulated. Even if her gesture is not equivalent to a real withdrawal from work –since it overlooks the bio-political dimension of current modes of production, and, more importantly, the ambivalences inherent to the idea of «free time»–, it militates for an awareness of the difficulty of such withdrawal. And yet, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours does not fall into a discourse of hopelessness. Instead, it deeply resonates with those theorizations that have suggested a new political prospect for the overcoming of capitalism through the rejection of the employment society. Accordingly, Eichhorn’s piece is not only an experiment but also a political statement, a gap through which other ways of thinking about work and life are possible.