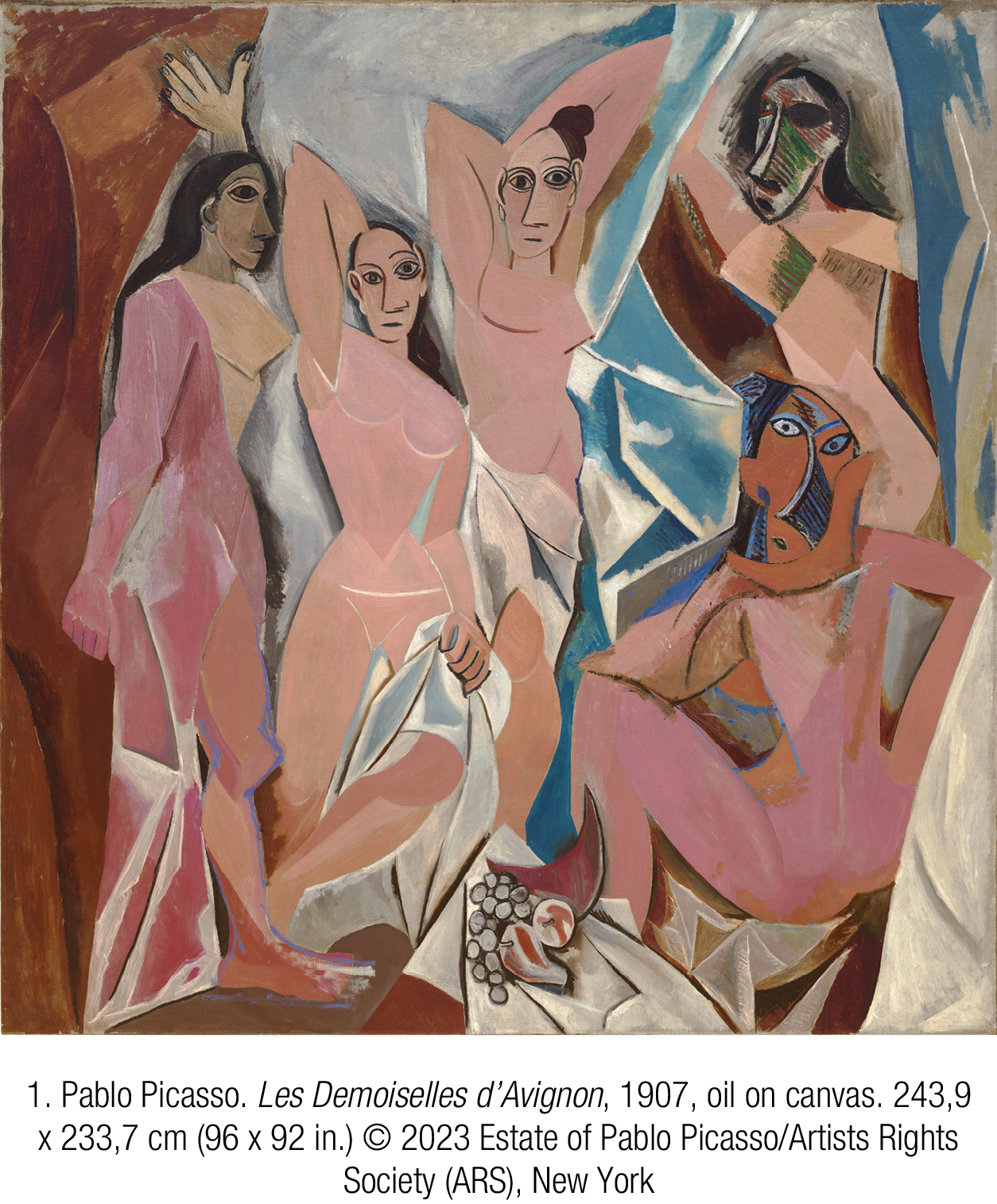

What might Pablo Picasso’s landmark 1907 painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [1], contribute to today’s conversations about gender and sex? The curators of It’s Pablo-matic, the memorial-year Picasso Celebration exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum (June 2-September 24, 2023), would probably answer: «Not much». While that response mirrors some factions of public opinion on Picasso, especially in our post-#MeToo era, it also aligns with the critical history of this artwork’s gender dynamics. Almost as soon as Picasso finished painting the Demoiselles, critics started identifying all of its figures as cisgender, heterosexual females1, and often as prostitutes appearing monstrous and fearsome to a male implied spectator/client2. The most recent scholarly book on the Demoiselles tries to undo this demonization and to expand the painted figures’ roles beyond sex work, yet it still insists on their femaleness, «broadening the identities of the female subjects to be lovers, mothers, sisters, and daughters» (Blier, 2019: XIV).

With the gender of the Demoiselles long since settled and consistently reified, much recent criticism of the painting has focused on the two figures on the right, whose complex racialized constructions involve masks and the appropriation of African artifacts. The faces of the two central figures have the same basic color as their bodies, so they are assumed simply to depict white women. Yet they too have features that mask –that is, complicate– their visual presentations, including areas of inconsistent skin tones; some features also can serve to «masc» or masculinize these bodies. Elsewhere, I have shown that viewers can «flex» specific details in the painting to construct appearances of stereotypically male as well as female physiologies in the two central figures (Schiff, 2022). In this essay I point out other details that expand these figures’ gender presentations, and I argue that these specific visual strategies derive from a precedent that has not been previously considered – the famous classical sculpture, Sleeping Hermaphroditus (2nd c. CE)3.

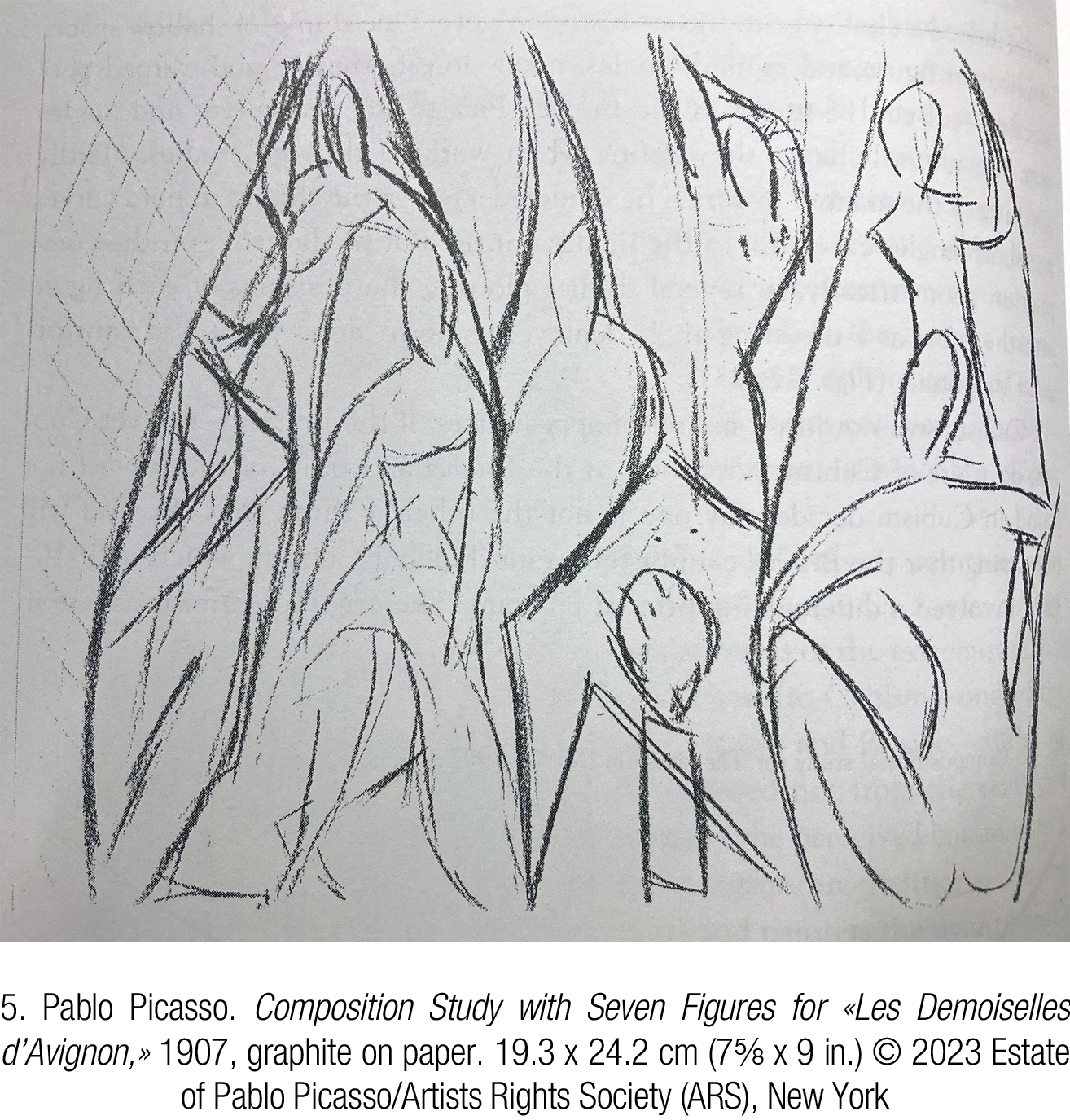

Though a few critics mention «doubly sexed» figures in relation to Picasso’s early 1900s work (Poggi, 2019: 98)4, none ties this sculpture to the Demoiselles. It is more common to find analyses of gender play in slightly earlier works by Picasso (Poggi, 2014; Werth, 1997). As for the Demoiselles, scholars do discuss preparatory sketches of masculine figures (Steinberg, 2022: 43-45; Bois, 1988: 37-40; Rosenblum, 1986: 58-59), yet they often claim that these figures definitively «disappear» from the final painting or completely transform into feminine figures (Steinberg, 2022: 92-93, 96; Bois, 1988: 37-38)5. One recent critic notes only «androgynous silhouettes» in the painted demoiselles (Loreti, 2020: 233).

Gender as a theme in the Demoiselles became more important with the original publication of Steinberg’s 1972 essay «The Philosophical Brothel». This essay, lengthened in 1988 and reprinted with minor editorial amendments in 2022, remains the most important single work of criticism on the Demoiselles. It effectively shifted critical discourse on the painting from objective formalist analysis to the psychoanalysis of a sexually charged, intensely subjective face-off between nude females (lower-class prostitutes on display in a brothel receiving room) and us (the spectator standing in the gallery who poses as their client). As I reorient the visual perception of Picasso’s two central figures away from categorical and fixed gender presentations and toward a connection with the Sleeping Hermaphroditus, sometimes I will use Steinberg’s own observations to help unravel the certainty of affixing femaleness to figures that are not necessarily just «demoiselles»6.

When I analyze images in detail, however, I do not intend a forensic, medicalizing gaze that seeks to assign to these bodies fresh or «true» gender identities. Instead, I bring forward arrangements of signs whose visual significance can be continually reinterpreted to resist gender closure and categorization, playing with conventional expectations of figuration7. The Demoiselles, one of Picasso’s most canonical works which has long been regarded as a revolutionary break from established aesthetic and art historical norms, now also will include a dimension of gender revolution. At this moment, when we are revisiting entrenched narratives about art history (and Picasso), a thorough exploration of the two central figures and their gender-plural, classical precedent can compel us to rethink what has been said about the Demoiselles and its cultural impact, from the fin-de-siècle through today.

Twisting the central demoiselle

The most direct reworking of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus pose is found in the right central figure (occupying the painting’s prime meridian). The torso of this figure can be seen as if in rear view [2]: when the slightly browner triangle on the left side of the torso is regarded as negative space, the dark lines of the figure’s breasts can be seen as shoulder blades, and the line of the thigh crease at the groin can represent the cleft in buttocks turned sideways8. The reinterpreted figure has a twisting spine and a slightly raised left leg. The head still faces forward, swiveling 180º from the body; a sloping line of color distinction at the neck facilitates the disjunction between torso and head. This rear view still may initially appear female-coded, though the waist may be narrowed simply from torsion; I will address gender after giving context to the 180º twists of the torso and neck.

A 180º twist at the neck also appears in the crouching figure nearby, whose head critics often discuss as facing the viewer while the body faces the scene’s interior. Steinberg accounts for the croucher’s 180º swiveled head by observing that in some of Picasso’s works, as early as 1906, necks no longer necessarily look like they are connecting body parts9. Though the central figure in the Demoiselles has a neck, its flesh does not look volumetric. Instead, its two vertical outlines appear as a spatially flat, schematic neck-sign, presumably facing forward like the head (though this cylindrical body part actually can be oriented in any direction). The sloping line of color distinction then can serve to connect the head to the reversible torso, creating a joint of planes that swivel against each other.

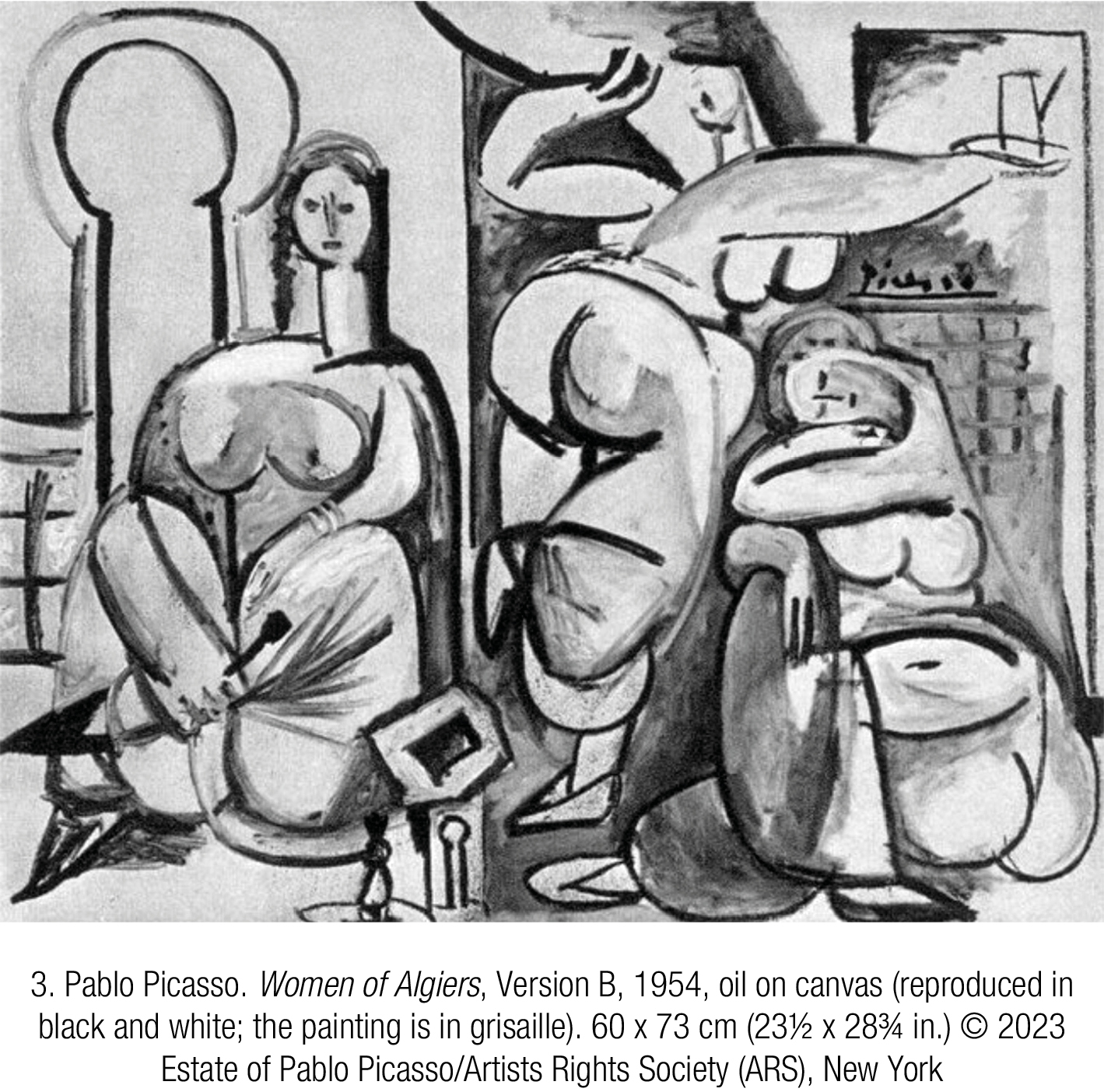

This swivel –and even more, the possibility of seeing the central figure’s torso as a back– is consistent with what Steinberg calls «Picasso’s lifelong obsession with the problem of simultaneous front and back representation» (2022: 216, n. 51). This problem also became Steinberg’s obsession: he explored it in three essays that first appeared in the early 1970s, all of which he revised and republished10. The most thorough of these connects early instances in 1907 (the year of the Demoiselles) to later variations on the theme, focusing on Picasso’s Women of Algiers series of paintings (1954-55) after Delacroix’s paintings of the same name11. Considering figures from one of Picasso’s Women of Algiers paintings will help to expand my discussion of the central figure in the Demoiselles, because this later series presents more legible versions of what I have pointed out so far in the Demoiselles12.

Gender complexity in the Women of Algiers

In many figures of the Women of Algiers paintings [3], breasts and buttocks are visible simultaneously and without any special effort to «flex» the viewing angle (or the depicted body) from one side to the other13. Of one of these –a figure that is both «coming and going», twisting to face front while walking back– Steinberg writes, «Hellenistic art had a type and a word for her kind of action – Venus respiciens, ‘she who looks back.’ In ancient art… it was felt to be adorably feminine to cast backward glances» (1972: 138-39). It is easy to identify the looking-back pose in the walking figure in the middle of the scene14.

Though this Hellenistic framework codes the bi-directional motif as «feminine», many figures’ heads in the Women of Algiers series look decidedly phallic. Steinberg notes that the left figure’s «erected head» in Version B rhymes with the «phallic» niche in the background, and that the woman’s buttocks and/or upper legs can be read as testicles (1972: 126-27). Yet this figure’s breasts also can double as testicles connected to that same head, and shapes of male genitals also can be perceived elsewhere in the canvas (as in several other Versions in the series). For example, the walking figure’s breasts can double as testicles beneath the phallic neck and head which rise beyond this figure’s outstretched arm. The phallic niche shape is repeated in the curious miniature at the bottom margin, along the painting’s central meridian15. This erection –topped by a diamond that recalls the similarly positioned «tabletip» in the Demoiselles16– appears far forward in pictorial space, and visually echoes a forward-projecting, centrally aligned erection in the Demoiselles.

Phallic imagery in the central demoiselles

The foreleg of the central bi-directional figure in the Demoiselles can also be seen as an erection [4]. A solid, dark contour line on the left makes this phallic form jut out in space to appear distant from the sketchier, draped thigh and the rest of the body. Anomalously smooth brushstrokes also make this area of the painting distinct from the rest of the painting.

I am not the only critic to claim that the Demoiselles contains this phallic image, though when I perceived the visual polyvalence I was not aware of these other instances. George Baker notes in passing «the erect phallus that the artist would otherwise have us believe is really the knee and lower leg of the central demoiselle» (Baker, 2011: 15), as part of a list of neglected gender-bending iconography in the Demoiselles (in his larger argument about gender-complexity, focusing on the squatting figure). George Smith lingers longer over this «tumescent penis» as part of a Freudian image of castration, especially when he reads this sign alongside a reinterpretation of the still life on the table below it (Smith, 2022: 161-62). This particular phallus is not remarked in other psychoanalytic criticism, however, including Tom Ettinger’s exhaustive catalogue of phallic imagery in the Demoiselles (Ettinger, 1989: 164-82). Yve-Alain Bois explores the Freudian framework of castration anxiety yet, after sketching out an iconography of erections other than this one, arrives at a Lacanian analysis of the painting’s oppositional conceptual structure, akin to Baker’s framework (Bois, 1988: 42-45). Smith conjectures that this persistent blind spot among critics «has to do with the dazzling, shocking, and indeed traumatic effect of the painting as a whole»; he also suggests that it is difficult to recognize a non-representational phallus that is «much, much bigger than the anatomical penis» (Smith, 2022: 161, 162)17.

This painted phallus does look typological, even mythic, instead of representational. Though it appears far forward enough to «belong» to the implied spectator, its ideational (or fictional) status does not require that this viewer have a penis18. Its separateness and symmetry suggest a dildo, or a sculptural phallus as is common in diverse art historical, cultic, and cultural traditions. Moreover, because it can be seen as emerging from the body of the often feminine-coded central figure, it can remain also as part of that gender-plural or gender-complex figuration.

In Picasso’s later sketches for the Demoiselles [5] y [6], this idealized phallic form seems to evolve from a flower vase and/or from a transposed client/sailor figure that is displaced from the center of the composition and whose head could become the glans of the penis19. These evolutionary paths suggest layers of significance beyond the narrowly sexual. Based on Picasso’s sketches of vases of flowers and figures holding funeral urns, the phallus could represent the conflation of opposing forces of vitality and death – an agonistic theme discussed by Steinberg (2022: 115-16) and especially by Rubin (1994: 36, 49, 58, 114-15)20. Or it could presage for the phallus of Lacanian psychoanalytic theory, the signifier of power which anyone can want but no one can ever thoroughly possess. In any case, this phallic image does not appear alone. And when seen part of the visual language of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus sculpture, it suggests a different set of meanings.

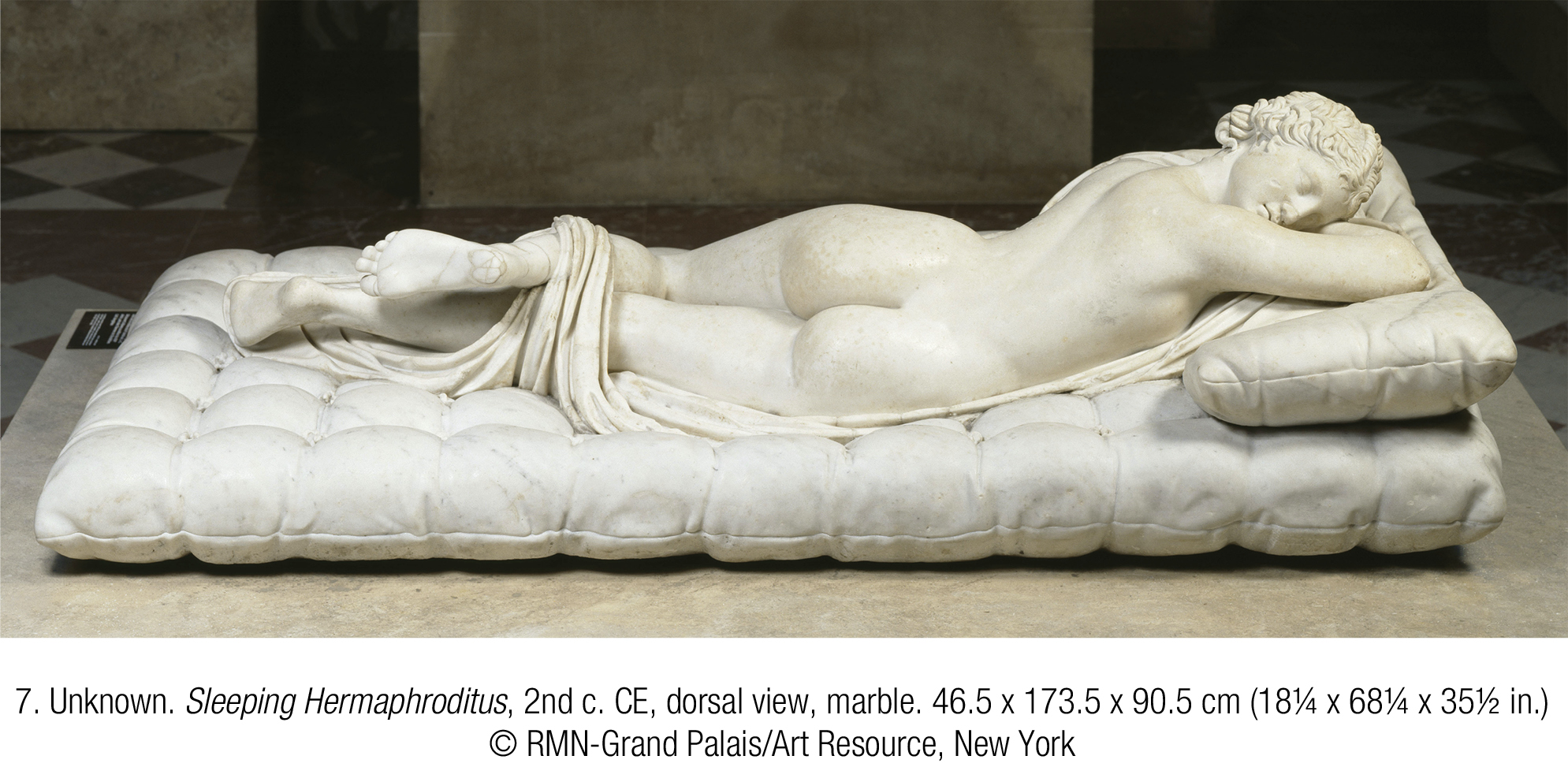

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus as precedent

The central figure’s hidden-in-plain-sight phallus –along with the twisting torso, swiveled head, bent and raised left leg, and elbows-up pose seen from the rear– all correlate to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus. This sculpture also accounts for all of the features I have discussed in Picasso’s Women of Algiers figures, and ultimately for the entire «problem of simultaneous front and back representation» in Picasso’s work21.

There are three main stages of viewing the Sleeping Hermaphroditus. First, the viewer approaches the sculpture in dorsal view [7]22. From this perspective the torso is twisting (as are the abstracted torsos in the walking figure of the Women of Algiers and in the the reinterpreted central demoiselle)23. The head turns to face backward –and toward the approaching viewer– in that characteristically Hellenistic «feminine» gesture that Steinberg identifies (which can be seen in both paintings)24. This gender categorization appears to correlate with a female sexual identity – a rounded breast is partially visible (from some angles) beneath the upraised arm (so that both breast and buttocks can be seen simultaneously, as in the Women of Algiers)25. The head rests on this arm, though the sharp twist of the neck (cf. the swivel joint in the Demoiselles) intensifies a restlessness in the pose26.

Walking around the sculpture reveals that restlessness also characterizes the figure’s sex/gender: in full ventral view [8], a penis is visible as well as another rounded breast27. The head facing away allows for a more probing, depersonalized gaze, and the surprise of seeing male genitals on a body previously perceived as female motivates the viewer finally to circle the sculpture again and discover cues for the initial misgendering. Long horizontal lines in the drapery draw the eye (and therefore the body) toward the ends of the sculpture, «always offering a return to the rear [dorsal] view and an invitation to linger there, to look again and again» (Trimble, 2018: 20)28. The genitals remain in the mind and unsettle the initial female categorization. It now becomes clear that the sculpture’s feminizing «looking back» pose has contributed to the narrative arc of an gender assumption and subsequent rethinking.

The body of the sculpture, now seen afresh from all angles, can look sometimes masculine, sometimes feminine; the same physical structures can be «flexed» into approaching either gender category, yet never fully or fixedly occupying it29. Viewing the sculpture with an agenda-free curiosity can lead to the ambiguous forms and contours of the sculpture unsettling –and even obviating or emptying– gender designations. Binary codes lose their distinctions and soon seem irrelevant as flesh (i.e., stone) becomes unfathomable. One translation of Ovid’s rendition of the now best known Hermaphroditus myth, from Metamorphoses, sums up the situation with an unexpectedly current pronoun (plus a poignant contradiction about whether Hermaphroditus is regarded as animate or inanimate, a gendered human being or an «it»): «nor could you say it was a boy or a girl, but they seemed neither – and both» (qtd. in Garland, 2010: 101)30.

This plural, inscrutable gender scheme is infused into the painted physiology of Picasso’s central demoiselle. One corresponding detail merits special mention: the foreleg/phallus in Picasso’s painting, when it juts forward in pictorial space, calls to mind the bent leg and flexed foot of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus. This lower limb also projects toward the viewer in the dominant dorsal view, where it can symbolically represent (and thereby hint at the existence of) the penis that is out of sight on the other side of the sculpture. The foreleg of the classical precedent only alludes to a phallus, while the central figure’s foreleg in the Demoiselles visually resembles a phallus. Still, both body parts contain the ambiguity of the «foreleg/phallus». As we perceive and interpret these body parts, as with the process of viewing the Sleeping Hermaphroditus and the central demoiselle altogether, our growing awareness of their ambiguities makes us realize how we are constructing and gendering our perceptions of these bodies.

Picasso and the Sleeping Hermaphroditus

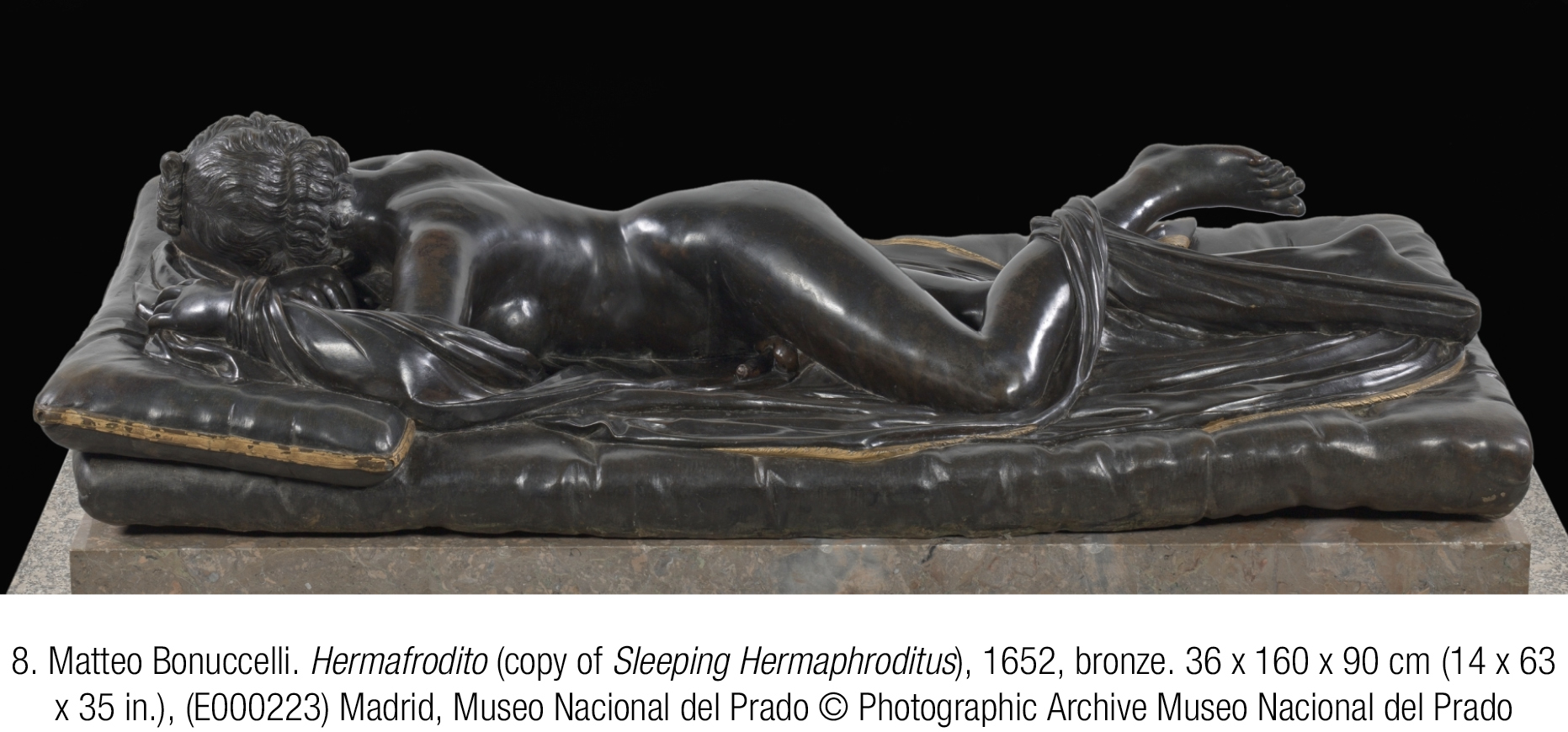

Picasso could have seen two versions of this sculpture easily. In the early 1900s, he likely saw the Louvre’s white marble version [7], when he was «haunting the halls» of the antiquities galleries at the Louvre31. This version, long known as the Borghese Hermaphroditus, was and is the most famous of all the copies of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus that exist worldwide (Ajootian, 1990: 82)32. Picasso also likely saw in the Prado’s sculpture hall the copy in dark bronze [8] that Velázquez commissioned for Spain (1652)33 – the teenaged artist spent long hours in that museum instead of attending art classes in Madrid in 1897 (Palau i Fabre, 1981: 135-38)34. Picasso’s well-known interest in sexual matters, plus his artistic interest in figural representation, make it likely that this sculpture would have captured his attention.

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus sculpture also was in the art news of Paris, about a year before Picasso began painting the Demoiselles: André Gide, in reviewing the 1905 Salon d’Automne, writes that Pierre Bonnard’s painting La Sieste, then called Sommeil (i.e., «slumber», a title that more directly corresponds to the sculptural figure’s liminal condition between sleep and wakefulness), features «the pose that’s quite close to the Borghese Hermaphrodite»35. Gide’s use of the definite article «la pose» instead of the more vague «une pose» suggests that any art-savvy viewer would have recognized the combination of bent leg, obscured genitals, spinal twist, and twisted head leaning on a flexed elbow (with a rounded breast partially visible beneath) as the visual echo of the sculpture. Leo and Gertrude Stein bought Bonnard’s painting from that exhibition, so Picasso could have studied the allusive pose not only at the public Salon, but also in the Steins’ private salon, where at that time he often attended Saturday night dinner gatherings36.

Picasso’s main artistic rival, Henri Matisse, also attended those gatherings and would have seen the Bonnard painting. Though the Demoiselles is often tied to Picasso’s having seen Matisse’s The Joy of Life (1905-06) and Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) (1906-07) –both also displayed on the Steins’ walls– it has not been considered that these works, too, could be regarded as reflecting on the visual and gender ambiguities of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus sculpture37. This connection becomes more pronounced when Blue Nude is considered in relation to the similarly posed sculptures that Matisse was making alongside that painting, such as Reclining Nude I (Aurora) (1906-07), alongside that painting. Critics occasionally see a phallic image in the iconic hip of Matisse’s Blue Nude (Kuspit, 2006: sect. 2)38, yet this and the Hermaphroditus-like poses in The Joy of Life are often interpreted through the lens of male heterosexual desire, especially a colonialist desire that sexualizes and exoticizes a «primitive» female «other».

These frameworks also have governed recent criticism about another famous painting that Picasso surely saw, soon before embarking on the Demoiselles –La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Ingres39– which was exhibited at the Louvre in 1906 next to Manet’s Olympia (1863)40. In the summer of 1907 Picasso made Odalisque after Ingres (MP545), in which the body appears to be orienting toward both directions at once. La Grande Odalisque, too, could be reinterpreted as formally related to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus41. While Olympia, painted roughly halfway between La Grande Odalisque and Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), is now being discussed in terms of gender complexity (Getsy 2022)42, the depiction of the courtesan Olympia is not as straightforwardly connected to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus43.

Both central figures

The features and gender implications of the Sleeping Hermaphroditus most clearly correlate to the most central figure in the Demoiselles, yet it is also possible to apply this expanded view to the painting’s left central figure. Given the «sibling resemblance» between these two figures44, it is reasonable to seek references to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus in both, much like we have found the allusion distributed among figures in the Women of Algiers.

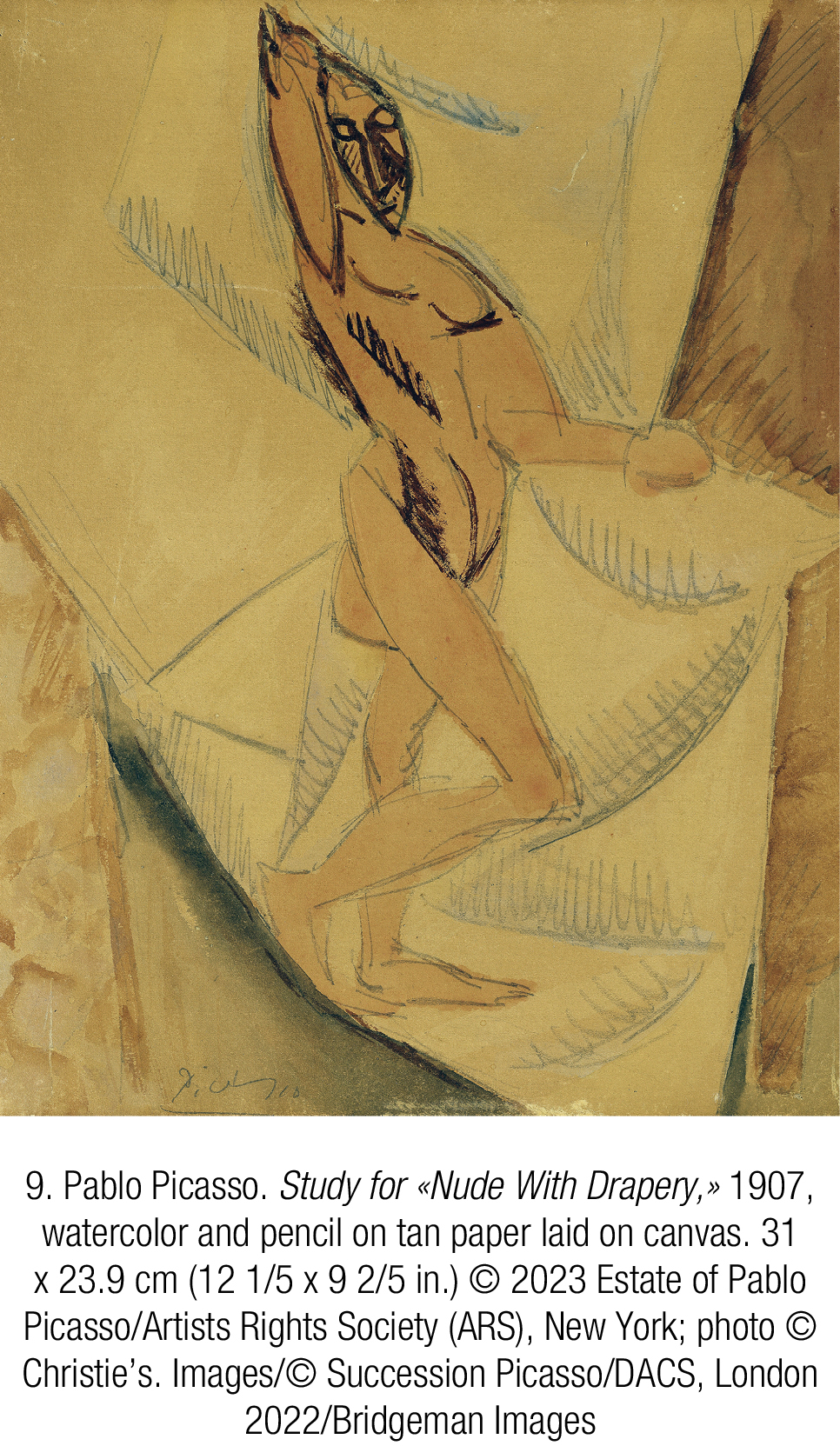

Many features of the sculpture’s iconic pose appear in Picasso’s studies for Nude With Drapery (1907); two of these studies (Z.II/1.45 and Z.II/1.47) have been discussed also as preparatory to the left central figure in the Demoiselles (Rabinow 2011: 40, 268). In these studies, as in another [9], only one arm is raised, and one leg bends so the forelegs cross – a pose that also directly resembles the Sleeping Hermaphroditus sculpture. Other features of this figure recur in Picasso’s right central demoiselle: the front of the pelvis can double as buttocks, breasts can double as shoulder blades, the outstretched forearm looks like an erection, and the torso twists prominently45.

In the left central figure in the Demoiselles, the sloping color shift at the neck recurs, so this head too can be seen as swiveling 180º to face the viewer. The unusually rounded breasts can then double as buttocks to create another type of dorsal view. Though the buttocks appear higher on the torso than in the right central figure, this surprising placement is consistent with the radical rearrangement of features that Steinberg observes in Picasso’s work beginning in 190746. This extraordinary mobility of position offers a visual correlative for the potentially abrupt malleability of sex/gender.

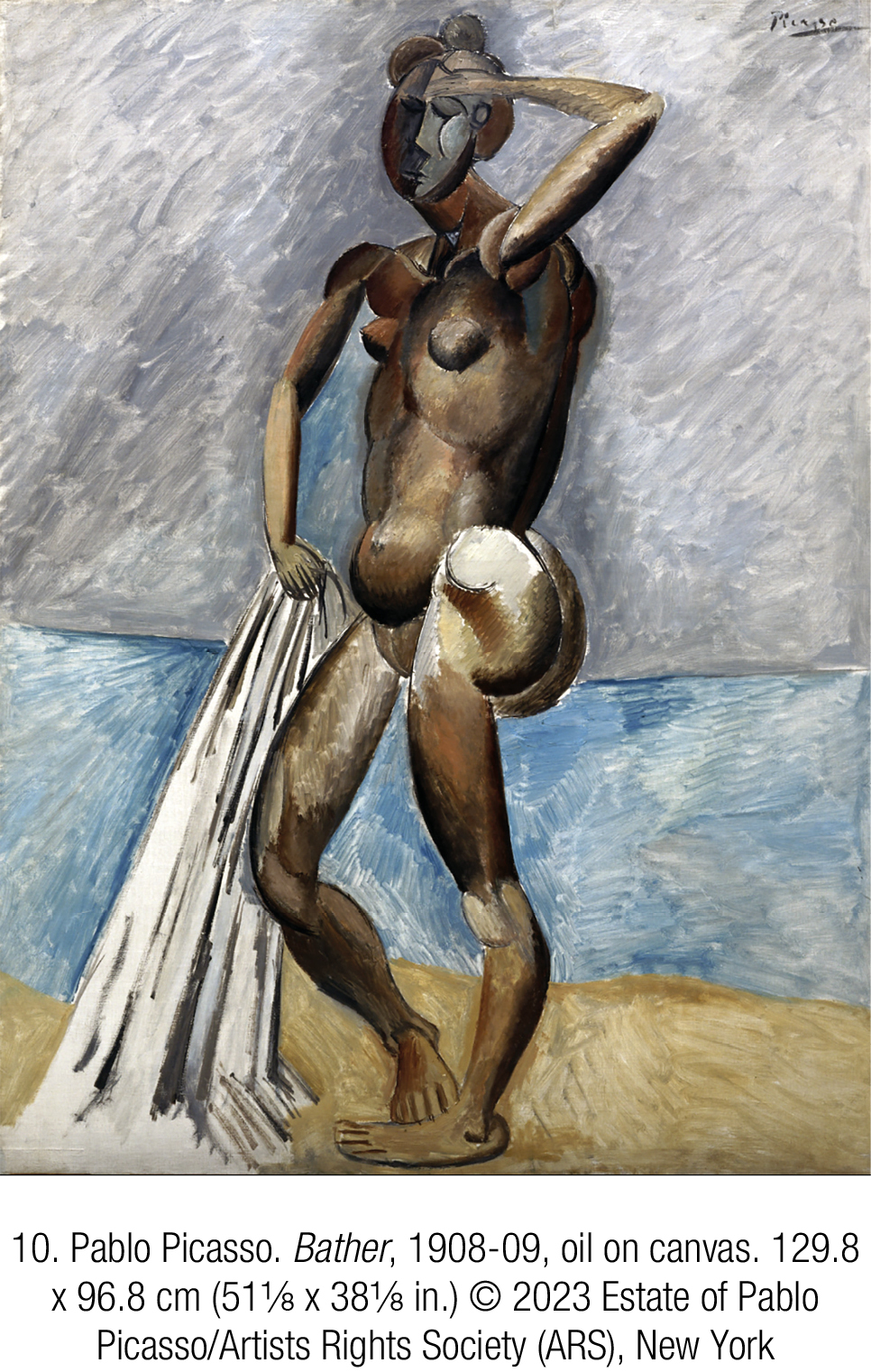

Phallic imagery also appears: the left central figure’s only upraised arm emerges from a white «v» of the armpit, and a very similar white «v» signifies this figure’s vulva (the only exposed genital area in the painting). The illusion of the upper arm as a penetrating phallus is more prominent in sketches (including fig. 9. [9] where the elbow sprouts a testicle): the final painting retains a testicle-like shape in the bulb of flesh near the tip of the upraised elbow. Picasso’s slightly later painting of The Bather (1908) [10] shows this illusion of –or allusion to– sexual penetration more vividly. The raised upper arm of this bi-directional figure (whose pose again evokes an upright Sleeping Hermaphroditus sculpture) stands out in the painting as a volumetric, engorged form that emerges from and/or enters the rounded, engorged crescent-lips forming the armpit.

Interpreting the allusion

The consistency of Hermaphroditus-related imagery in these figures implies that the two central demoiselles now share a structural concept with the other three demoiselles: conflating «opposite» identities within a single body. While the three «marginal» figures are racially bifurcated (because their faces have such different coloring from the rest of their bodies), the two «central» white-appearing figures combine binary gender cues. (Both of these bodies contain many shades of their skin tones, which suggests a racial ambiguity as in the earlier odalisques). This general conceptual scheme of conflating «opposite» identities relates closely to Baker’s argument that the equivocal pose of the squatting demoiselle (conflating dorsal and ventral views, and folding together vectors of upward and downward motion) represents «the body proclaiming that all structural oppositions are off». This formal strategy has a conceptual valence, as it «seems to call into question oppositional thinking itself» (2011: 31, 28). Baker also articulates this as «a ‘making multiple’ of the body» which serves as «the exact opposite of totalization» (2011, 24). I propose that this non-totalizable multiplicity he finds in the squatter’s body, and its inherent critique of categorical identifications, can be found in all of the demoiselles, most immediately visible through the signs of plural racial identity, and now also in the representation of plural gender. The latter has a powerful precedent in the third stage of viewing the Sleeping Hermaphroditus.

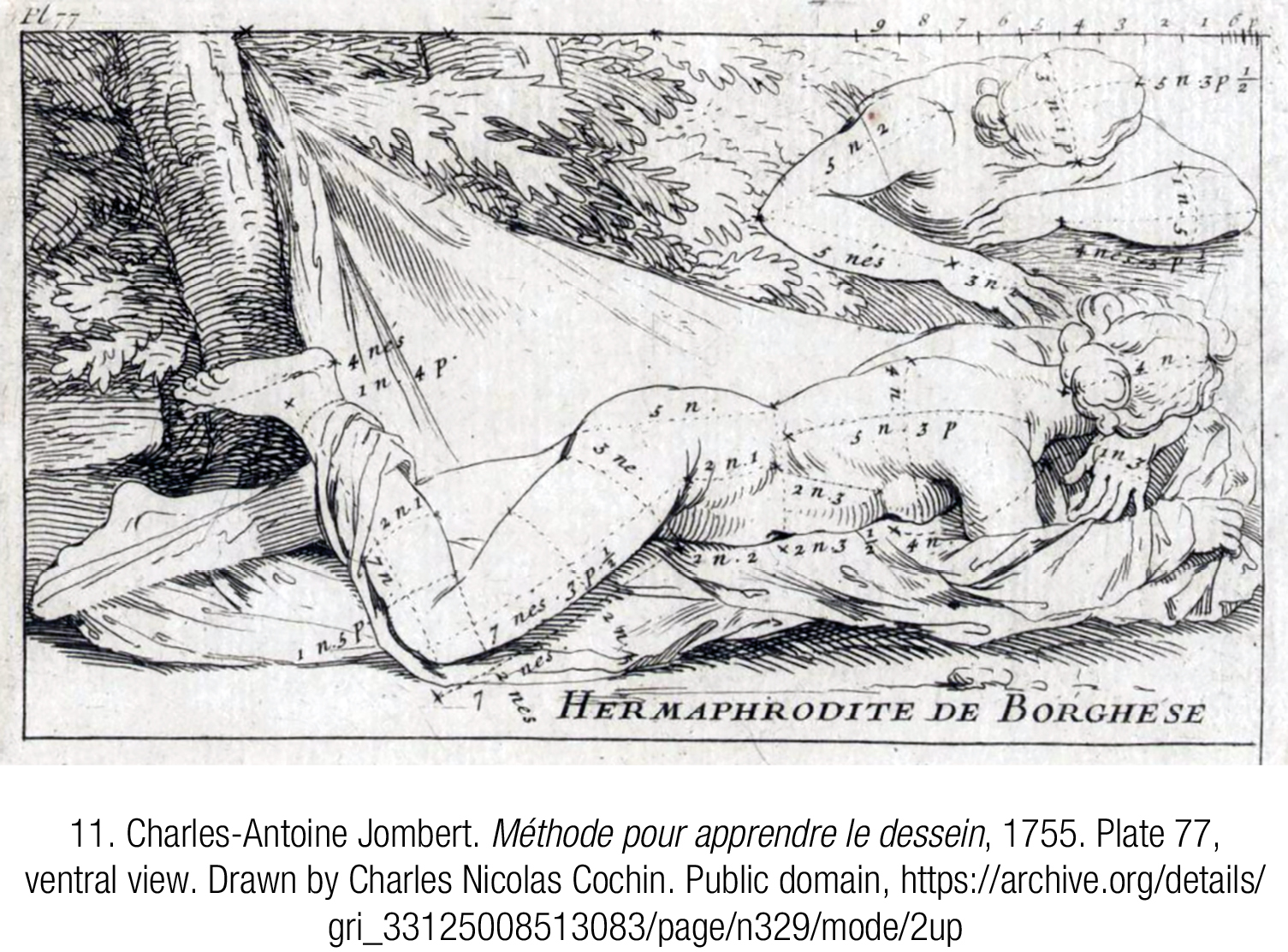

It makes sense that the Sleeping Hermaphroditus has not been proposed as a precedent for the Demoiselles – hiddenness accompanies the sculpture at every turn. When the penis is initially concealed from the viewer, and is not even visible from all angles of the ventral perspective, this invisibility gives it more impact once glimpsed. An eighteenth-century drawing manual pictures the sculpture from both sides (Jombert, 1755: plate 77) but with the figure drawn to shield the penis from view [11], though other classical sculptures of male nudes in the same manual are not similarly censored. By completely obscuring the sexual surprise, this manual simultaneously desexualizes the sculpture and implies that its physiology is too transgressive to view, even through the mediating technology of a book. Another book – a late nineteenth-century Baedeker travel guide, often reprinted – says that the sculpture is «too sensuous in style», a judgment that directs attention to formal qualities and sublimates sexual content while also sounding discouraging to tourists47. The phallic imagery in the Demoiselles, which may remain obscure unless the viewer looks for it, reproduces the history of hiddenness associated with the Sleeping Hermaphroditus, both in the sculpture itself and in the literature about it.

Why bring this comparison out of hiding now, especially at a moment when the centrality or even presence of the Demoiselles in art historical narratives is being reassessed? The current art historical project of decolonizing the canon inspired Coco Fusco’s ultimate question to Suzanne Preston Blier, in a 2020 interview about Blier’s 2019 book on the Demoiselles: «What would you say about the importance of still returning to ‘European masters’ in an era in which some are thinking that perhaps they take up too much space?» (Fusco 2020: 50:21-51:42). While I inevitably add to the already enormous literature on Picasso, I seek not to reinscribe his genius but to claim that this still influential painting’s gender complexity troubles assumptions of a patriarchal gaze associated with those «masters». If we can redefine that gaze in both Picasso’s work and the narratives built around this painting, what other rewritings might become possible?

This direction could occasion another type of pushback which also merits attention. Decades ago, Carol Duncan accused Steinberg of trying «to save [one of the] art-historical ‘greats’ whose phallic obsessions have lately gotten embarrassing by fitting them out with new, androgynous psyches» (1990: 207). I am not trying so «save» Picasso. I am indeed interested in recontextualizing historically pivotal artworks that now are reductively sidelined as politically regressive. This is not to «save» a classic artwork either, but to open possibilities for ourselves as observers and critics. Those writing in a Freudian tradition may still choose to interpret the Hermaphroditus allusion as underscoring «Picasso’s fear of the empowered phallic woman» (Poggi, 2014: 35); I am more interested in this imagery’s potential effects on viewers.

Finally, I am aware that references to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus do not necessarily imply a challenge to conventional sex/gender systems48. In the eighteenth century, Horace Walpole reported that his aunt, Lady Dorothy Townshend, regarded her nephew’s bronze miniature of the sculpture as the emblem of a harmonious heterosexual marriage49. Yet in the mid-nineteenth century, Swinburne’s poem «Hermaphroditus», written in the presence of the sculpture at the Louvre, helped to spark a British literary scandal50. One reviewer denounced the poem’s unsettling effect, saying it would «produce in the the reader… a ‘physical commotion in the frame – a flutter of the blood’» (Seagroatt, 2002: 41). Here the Hermaphroditus threatens an inner sense of order, though it is not clear whether this agitation leads to a welcome of new paradigms, a reification of old ones, both, or total breakdown.

These contradictory responses to the sculpture seem typologically consistent with the gender-plural imagery in both Picasso’s painting and its classical precedent. Gender remains mobile and inconclusive, both in its visual manifestations and in the viewer’s responses to these provocative artworks. From today’s standpoint, the Sleeping Hermaphroditus allusion at least offers alternative frameworks for thinking through gender in the Demoiselles and in other paintings of «female» nudes by Picasso and by others. Current discourses of genderfluidity, intersexuality, transsexuality, and genderqueer and transgender identity perhaps have facilitated the perception of this gender complexity, and they also can help to expand its interpretation51. The Sleeping Hermaphroditus and Picasso’s gender-plural, semiotically assembled figures, while mythological in origin, do evoke the physical bodies that are now associated with these identities, and hopefully others can explore what this evocation might mean. Meanwhile, within the visual mechanics of these artworks, the very iconographies that cue us to identify bodies using stereotypically binaristic sex/gender codes also can serve passages where that binary system unravels and dissolves.

Deconstructing and continually reconstructing the central figures’ gender is a very different activity from what viewers of the Demoiselles have long been assumed to be doing while looking at a painting of female-presenting bodies arrayed in a brothel. The spectator now can play the role not just of a client or visual consumer of female bodies, but also of a philosopher of sex and gender.