1) It is forbidden to look at women.

2) It is forbidden for a girl to pay attention to her body while bathing, or for girls to look at the bodies of each other. Girls must wear a robe underwater.

3) Friendship is forbidden between girls, and anyone engaging in such friendship will be punished severely. No girl shall be left alone with another.

4) It is forbidden to read alone, or to purchase one’s own books. Therefore, our things will be searched continuously (Efflatoun, 1993: 20-21).

Egyptian painter Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989) could recall these prohibitions – just four points pulled from the severe regulatory regime of the Sacré-Coeur school she attended as a girl – for as long as she lived. Propriety had mattered in Cairo’s elite circles, and even though Efflatoun’s family was Muslim, her father sought the discipline of Catholic school for his daughters. Efflatoun could remember her first defiance of these rules as well. At age twelve, she played hooky from school so as to indulge in the adventure novel White Fang (1906). This gave her a taste of escape and she soon convinced her mother to allow her to transfer to the Lycée Francais, where she studied French philosophy and some Marxist theory. Before even completing her baccalaureate, Efflatoun had joined the anti-imperialist campaigns of Iskra (a leftwing youth group), thereby inaugurating what became lifelong work to betray the class interests of the haute bourgeoisie in solidarity with Egypt’s dispossessed. These are the political commitments that later landed Efflatoun in prison, in 1959, when then-President Gamal Abdel Nasser cracked down on Communists as supposed enemies of the state. They are also the commitments recognized as giving ethical shape to different aspects of Efflatoun’s painterly work.

Many writers have documented Efflatoun’s activism as a factor in her artistic decisions, typically placing focus on the drama of her efforts to reconcile the antinomies of her personal biography: a wealthy person seeking solidarity with the poor (LaDuke, 1989). As Egyptian reporters never tired of describing, she was a well-kempt and well-connected agitator; a «communist who owns forty dresses» (Efflatoun, 1993: 98). Much less considered in the scholarship, however, is her negotiation, through painting, with the controlling technologies of visibility that both buttressed and sometimes blocked her political claims as a radically creative and female subject. This essay seeks to provide an account of Efflatoun’s painting that attends to the conflicts around gendered appearance that we see in the images themselves. Specifically, hers is a corpus of paintings that resist conventional relationships between «figures» and the sources of light that might make them visible. As Efflatoun’s recollection of Catholic discipline helps to remind, the somatophobia of modern girlhood – a term I take from Elizabeth Grosz’s assessment of the fear of the body found in Western philosophy – doubles as a politics of recognition and misrecognition (Grosz, 1994). I here examine the psychical structuring of visibility in different phases of Efflatoun’s career, comparing the dynamics of somatophobia in her early surrealist paintings to that apparent in her «white light» (al-dawʾ al-abyad) paintings during the 1970s. The pairing reveals the artist’s conceptual play with relations of subject and object across Egypt’s shifting political regimes and raises new questions about pathways for claiming (and refuting) kinship and solidarity around gender.

Efflatoun had witnessed the predicaments of the female political subject before she even set foot in school. Her mother, Salha Efflatoun, who had married at the age of fourteen, divorced at nineteen (in 1924, the year of Inji’s birth), precipitating great social and economic upheaval for the family. It was not until 1936 that Salha managed to claim her independence as a single mother, when she launched Egypt’s first fashion house, Maison Salha. The enterprise represented a new way of capitalizing on social status, and was backed by Talaat Harb, a banker and nationalist entrepreneur who sought to develop the country’s cotton industries as leverage against foreign interests. As art historian Nadia Radwan has noted, modernizers in Egypt, as elsewhere in this period, took up the notion of the «new woman» as a focal point for perceived changes to the social order, with the fashionably dressed woman standing as both reflection and initiator of change (Radwan, 2016). These self-consciously shifting categories, tied as they were to regimes of consumption, proved to be double-edged for the Efflatoun women. They emancipated Salha from her family’s direct patronage, but they also made her dependent on the circles of the Egyptian monarchy and their tastes.

The family’s position of privilege conditioned Inji’s path to acquire training in drawing. As was common for privileged Egyptian teenagers in the period, she took lessons with tutors drawn from the country’s large pool of French-speaking intellectuals. In 1940, her mother hired as a tutor the famous avant-garde figure Kamel el-Telmisany, a writer, painter, film-maker and founding member of Art and Liberty, a coalition of Egyptian avant-gardes who espoused international surrealism as a model of anti-fascist resistance. Telmisany’s «bewitching» pedagogy reflected the emerging sense among his circles that drawing offered a means for liberating otherwise repressed perceptions of social clashes, as might serve, in turn, to prompt political transformation (Efflatoun, 1993: 30). In his writings, Telmisany advocated for authentic arts of intuition, doing so by reference to both the latest French writing on the subject of surrealism and arguments for the internationalism of fundamental commitments to freedom of expression, style, and imagination (Lenssen, et. al., 2018: 101-4). Efflatoun worked through the jolt of these exchanges in her painting. We see depictions of the interior subjects of gendered, classed anxieties: dream imagery of vengeful trees, creeping vegetation, and serpents that grasp at other beings – including frightened young women – as day turns to night.

Efflatoun later described how socialism had, in the fraught decade of the the 1940s, seemed to offer a pathway to solving the problems of Egypt’s social inequalities that proved both just and rational (Efflatoun, 1975). It was a mode of analysis as well as an ethic. To this initial characterization of the leftwing project, the avant-garde members of Art and Liberty added a key provision: the irrational, too, was to be understood as liberating. Their group recognized images, whether in dreams or paintings, as agents within the otherwise exteriorized capitalist economy. Consider, for instance, how fellow Art and Liberty affiliate Ramsis Yunan’s 1940 essay «The Dream and the Reality» articulates the political potential of surrealism’s Freudian materials (Yunan, 1969: 36-42). An exploration of the imperial origins of modernity, the text outlines the deep contradictions of the era, including reading the «consumptive workers» in Talaat Harb’s urban factories as the sacrificial subjects of modern plenty. As Yunan knew, the preceding years had been marked by the rapid expansion of labor in the Egyptian textile sector, alongside strikes, a bank crisis and economic depression. Against these structural crises, he argues that the fact that workers continue to dream and play host to unbidden visions can be understood as the human capacity for revolution. The essay’s metaphors of haunting and spectral inhabitation – it describes the fear of hunger perching over the city like a ghost, holding its inhabitants down until night-time – offer an additional interpretive key to Efflatoun’s early imagery. The painting The Girl and the Beast, for example, which she exhibited with Art and Liberty in 1942, is a landscape of heavily outlined bushes and cacti beneath a sulfurous night sky populated by alienated beings, including a large, transmogrifying bird and a tiny, flying girl [1].

Images commanded real powers, in other words. They were also becoming increasingly mediated in these years. As Georges Henein, a leader of Art and Liberty, declared in a 1939 speech, even the most distant signs of distress had begun reaching artists instantly by «radio, cinema, the press – wonderful, unexpected means of human communication», with the result being that art was opened to the social melee (Kober, 2005: 197). Critical vocabulary crossed between media forms. Responses to Efflatoun’s The Girl and the Beast, which employed a colorization technique of outline and tone resembling glass painting, often mobilized cinematic concepts, describing the images as akin to light projections. Henein described the painting as communicating by means of an «expressive transparency» achieved by Efflatoun’s placement of dream elements in spaces that seem to emit light from underground (Efflatoun, 1985: 99). The cinematic point of reference helps to charge the titular «girl» of The Girl and the Beast with a vexed significance – pleasurable in form, yet threatening in content – of the sort that Laura Mulvey later diagnosed in the 1975 essay «Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema». Occupying the place of psychic projection, she is a mummified figure in a blue party dress that embodies the gendered shame of being examined within a field of spectatorial desire.

Other women artists in the Art and Liberty group testified to questions of vision and power. In 1941, the photographer Hassia described the capacities of her camera in terms of inverted power: «photography allows me to escape one man and possess all men» (l’Art Indépendant, 1941). She was negotiating, among other things, the right to take a picture on command and to apprehend her subject. We find some of this same questioning in Efflatoun’s drawings from the decade, albeit in the coded fashion of social allegory. A suite of ink-on-paper works probe both the glittering duplicity of modernity and the false consciousness of religion in ways that put women subjects at the center. One shows a mendicant leaving a ruined forest to approach a housing development defined by hostile interiority, a tragedy witnessed by a young woman’s head depicted in sightless profile. In another, a young woman sits in a modern living space, shielding her face from an unholy apparition of gnarled roots and hair. And another drawing makes use of outright Christian imagery, of supplication to a creator: a forest chapel becomes an interior choked by votive smoke converging upon a crucifix [2]. The dynamics of looking at another woman is paramount here, for the viewer sees only the backs of the women kneeling in prayer, their eyes presumably shut to the profane world of the living.

Although Efflatoun shared the members of Art and Liberty’s aspiration to worldly solidarity, she soon grew involved in feminist campaigns that aimed at results in local Egyptian systems. Having joined the Egyptian women’s movement, she petitioned the state for suffrage and political rights. In 1945, she attended a much publicized conference in Paris organized by the Women’s International Democratic Federation, using it as a platform for decrying the British occupation as an element in the suppression of the rights of women (which, in turn, consolidated her position as a communist in the eyes of the Egyptian intelligence apparatus). For a few years, she gave up art altogether so as to devote all her time to organizing. She also got married in 1948, to a leftist lawyer who was later imprisoned and died in 1957, not long after his release. When Efflatoun did return to art in the early 1950s, it was not as a surrealist working in the service of a revolution of dreams. Instead, she plunged into the outdoors, painting under the blazing sun of the Nile Delta, at the nexus of the earth and laboring people. She also sought to achieve political activation in the work. At her first solo exhibition, which was held in Cairo only four months before the 23 July 1952 Free Officers’ coup d’état, she captured the angry anxiety of the times in paintings of martyred sons and clashes with British occupying troops [3].

Efflatoun had learned early that success in activist work often rested upon attracting external attention and pressure. In the 1950s, she and others became engaged in using the international stage to secure support for ambitious, free art practices based on direct experience of (what they considered to be) the real Egypt. Recent scholarship by art historian Nadine Atallah fills in the details of efforts by companion artist in Egypt, Micaela Burchard Simaika, a cosmopolitan figure of Swiss origin with a background in anti-Nazi resistance, to secure Egyptian representation in major exhibitions (Atallah, 2019). Efflatoun and Burchard Simaika together set out on painting trips to capture Egypt as a territory connecting ancient life to current agricultural labor. They went to Luxor and Baltim, painting peasants and fishermen at work, and paid a visit to the tapestry workshops in Naqada. In the same period, Efflatoun resolved to avoid bringing models into the studio and to always complete her paintings while immersed in the energies of a place2. In 1953, Burchard Simeika succeeded in organizing an Egyptian national contribution to that year’s Sao Paulo Biennial and compiled a docket of paintings meant to be expressive of Egyptian emotional traits. Later, when the initiative met with criticism from local commentators who protested the group’s lack of official qualifications, it was Efflatoun who published a defense in the press citing artistic freedom and advocating for trust in artists to make their own selections. At base, she and her collaborators upheld an essentially modernist desire to represent Egypt positively as a bastion of experimentation and to refute the absenting hierarchies of 20th-century colonial occupation, which would take Egyptian modernism as backward and belated (Salem, 2018: 248).

None of Efflatoun’s public achievements in the name of Egypt would shield her from the ever-expanding paranoia of the Egyptian security state during the presidency of Gamal Abdel Nasser. In 1959, as part of a wide crackdown on communist activists, Efflatoun was arrested, making her one of the first Egyptian women to be held as a political prisoner. Intriguingly, her subsequent commentary on her years in prison convey the impression that she welcomed the radical contraction of her world, for it gave her a pathway to merge more fully with regular Egyptians (Efflatoun, 1975). She speaks of the experience of the women’s prison as an enrichingly human one, wherein gender and class differentiation was levelled (LaDuke, 1989: 479). Such positive characterizations necessarily produce some skepticism on the part of a reader today. The sentiment may constitute a defiant assertion of survival, an expression of pride to have posed a threat to the status quo that is equal to men, or, just as plausibly, acquiescence to the Egyptian state and its terms for rehabilitation. Yet regardless of this complicated tangle of obligations, it is clear Efflatoun took the mental demands of shared incarceration as meaningful training in her political life. Prison prompted a resignification of her celebrity as an artist; as she describes in her memoirs, she leveraged her status as a recognized painter to procure permission from the warden to paint in prison. It also affected her experience of optical vision. Efflatoun states that the reduction of her liberties enhanced her capacities of aesthetic apperception, intensifying the wonder of even the smallest quantum of nature available to her gaze (Efflatoun, 1975). Her paintings offer a poignant amalgam of romantic regard for the expansiveness nature and the genuine material limits of the prison. They show windows but not openings. Cardboard supports are filled with the heavy impasto presence of blossoms and trees, blocking in the painting-as-window with the pigments she had so carefully procured by bartering ([4] second painting from left).

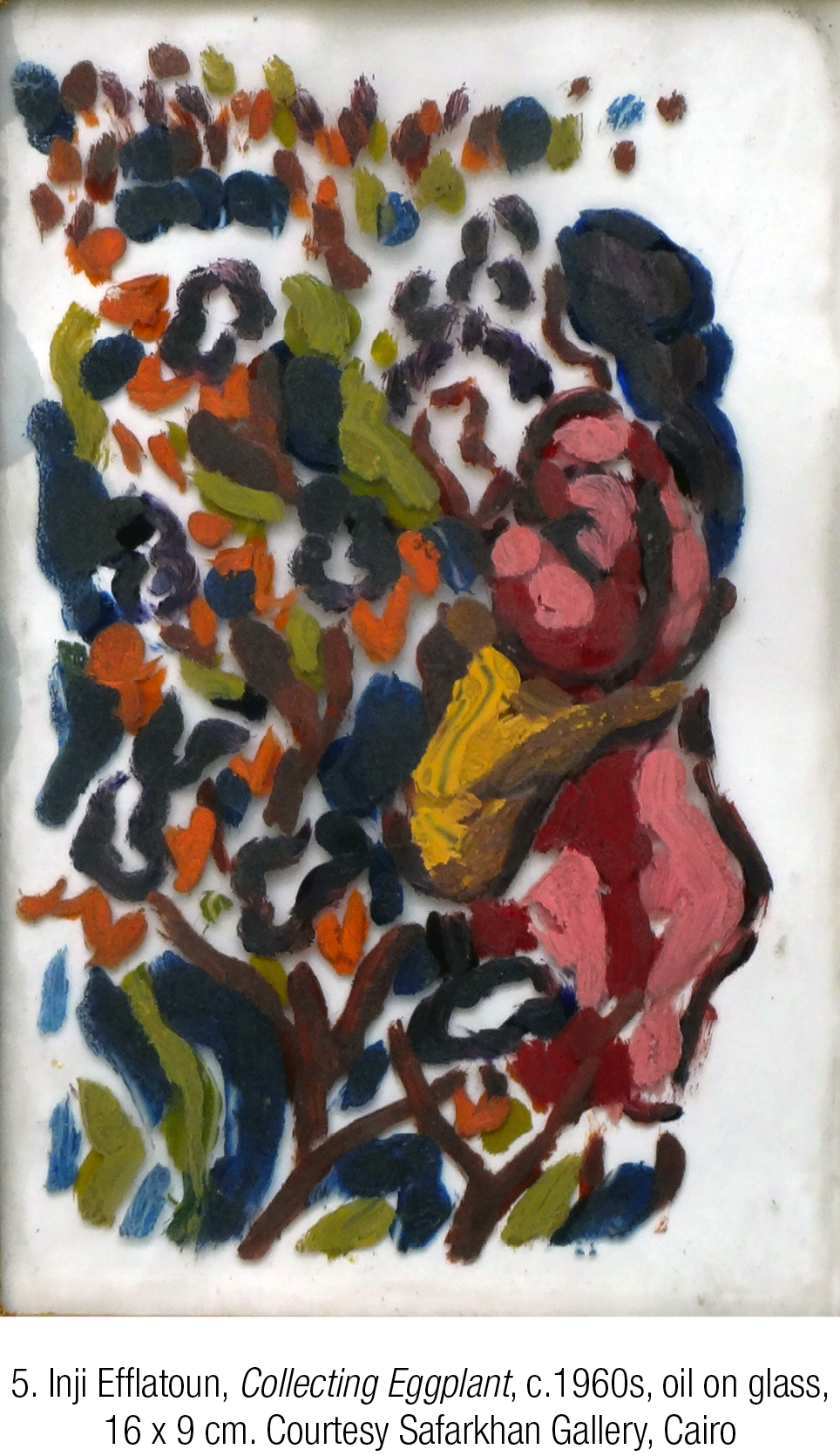

When Efflatoun was released in July 1963, her family took her to the countryside – to its immersive outdoor territories of farms, fruits and palms. The landscapes she painted at this time would seem to document how her freedom entailed a return to light as an agent that manifests in colors and forms. They negotiate the open air as optical experience rather than as touchable stuff. Primary colours appear as vibrating filaments and braids, offering themselves as the light-filled after-images of her imprisonment. That Efflatoun was interested in capturing the dramatic effects of this sudden inversion – from interiority in the carceral sphere to an unbounded exteriority – is evident in her decisions to experiment with the relationship between her represented object and its support. For instance, in 1964, she completed a series of sketches on glass, each showing a female laborer amid flecks of color and positioning the composition in a transparency [5]. These works become fully visible only when placed against a white backing, which, by dint of its opacity, reveals the positive image. If 1940s paintings such as The Girl and the Beast appear almost as a celluloid frame, such that depicted objects glow with dark illumination, then Efflatoun’s post-prison paintings make use of surface as a sheet of enveloping and therefore unifying light.

Efflatoun underwent a surprisingly rapid rehabilitation in the national cultural apparatus following her release. In 1965 she received a government fellowship to support her painting full-time, the following year she exhibited in collective shows in Egypt, and by 1967 she was presenting work in solo exhibitions in Rome and Paris. By then, her paintings were tending toward folded dashes of color in a spare yet expressionist mode, producing different sites and entities: rock formations in Aswan, banana groves, small villages perched upon cliff faces. Many dashed compositions approximated landscapes and horizontal rock flows. Coverage in the Egyptian press emphasized the formal innovation of the white space surrounding her «dynamic forms» (Arab Observer, 1966: 32). Other paintings, including the one that appeared on the cover of the brochure for her Paris exhibition, filled the picture plane with flowering, vegetal striations without any regard for a horizon line [6]. Yet these new concerns were not easily accepted by those who had known Efflatoun in the early decades, and they elicited ambivalent comment from such former comrades as Georges Henein. Having left Egypt for Paris years earlier, Henein was working as the editor-in-chief of Jeune Afrique and he published a short review Efflatoun’s exhibition that summer. Writing that Efflatoun had given up on an attitude of opposition in her work, Henein cast the artist’s retreat into artistic concerns – namely, the interrelationships of light and color – as a relatively hollow one. Although he affirmed that Efflatoun had continued to take as a subject the downtrodden laborers of the countryside, he suggested that she had transposed its meaning into a register of artistic joy and pleasure in manipulating her media of light and color (Jeune Afrique, 1967: 59-60).

Importantly for tracking the intersection of theories of gendered vision in Efflatoun’s, we must note that Henein also makes reference to the question of subject positions in his review. Specifically, Henein writes that the landscapes show nature as it manifests «to a woman», which is to say that they present nature in its almost fructifying plenitude. «Heavy with sap», the vegetation «imposes itself» on the artist. This is an unusual diagnosis of the intersubjective dynamics between painter, painting, and painted things. By way of contrast, commentary in an Egyptian tourism magazine characterizes Efflatoun’s process as a response to an artistic dilemma produced by the experience of living in an Egypt that is modern and yet not entirely Western in its outlook: how to study the effects of intense light on objects in a scientific manner while also, concomitantly, seeking to achieve a more Eastern state of «perfection, purity, and crystallization» (Egypt Travel, 1967: 37). Henein’s assessment raises a wholly different dilemma, and one familiar from the surrealists’ habit of characterizing «woman» as a modern fetish within both patriarchy and capitalism. Having supposed that Efflatoun might refute such fetishized tropes, Henein interprets her pictures of hyper-floriated lands of plenty as elaborate evasions of the mastering gaze. Imagining that such landscapes might possess the power to impose themselves on the artist, Henein diagnoses the inverted agency of the artist who is disidentified from a masculine subject position. Might worldly light have flooded Efflatoun to the point of visual impairment? Does the world cast a spell on its female subjects?

It is not easy to generate a responsible answer to these considerations, which touch upon worries about feminist struggle broadly and Egypt’s regressive politics in particular (Salem, 2018). Given how many other onlookers have laid claim to Efflatoun’s oeuvre, the artist’s own intentions regarding her self-absenting techniques and saturated landscapes remain fairly obscure. Henein, for one, pays little heed to the historical parameters of Efflatoun’s continued work as a feminist activist. From the texts of the speeches Efflatoun delivered in the 1970s, we know she attended to the connections between class and gender under the pressures of capitalist imperialism (precisely the topic Henein seems to believe these paintings lack). Further, when Efflatoun depicted the cultivated outdoors, she typically drew scenes from the cotton and brick manufacturing sectors, both of which made extensive use of rural women laborers alongside men (Davis, 1989: 140). Efflatoun was under no illusions that the so-called «natural» fertility of the landscape was, in fact, automatic or free. To the contrary, such fertility was underpinned by the hard labor of Egyptian peasants and the national history of cultivation contained no evidence to support the coding of nature as feminine and industry as masculine.

By the 1970s, Efflatoun had reached a stage in her career when she began to stake out a retrospective viewpoint on her own work. She was tapped to organize a large exhibition of Egyptian women artists for the occasion of UNESCO’s «Year of the Woman» and she delivered a talk in Paris that testified to the personal genealogy for her understanding of «the woman» as a political and cultural entity (Efflatoun, 1975). Her text describes her relatively early awareness of class conflict in Egypt and outlined the several kinds of activist remedies she had sought. For her, it had always been obvious that agitation for the liberation of «Egypt» would have to be formulated as liberation of each Egyptian man and each Egyptian woman as well. A revolution that failed to achieve liberty for the most greatly oppressed – that is, women workers in the rural lands of Upper Egypt – would not be a revolution at all. The speech concludes by reprising the language of earlier anti-fascist struggles and their consciously anti-capitalist turn. As Efflatoun states, once the national struggles of the Egyptian people succeed, then the reconciliation of «all the national forces» will be facilitated. Only then will women know that they have fulfilled their role in moving the country toward a worthy future.

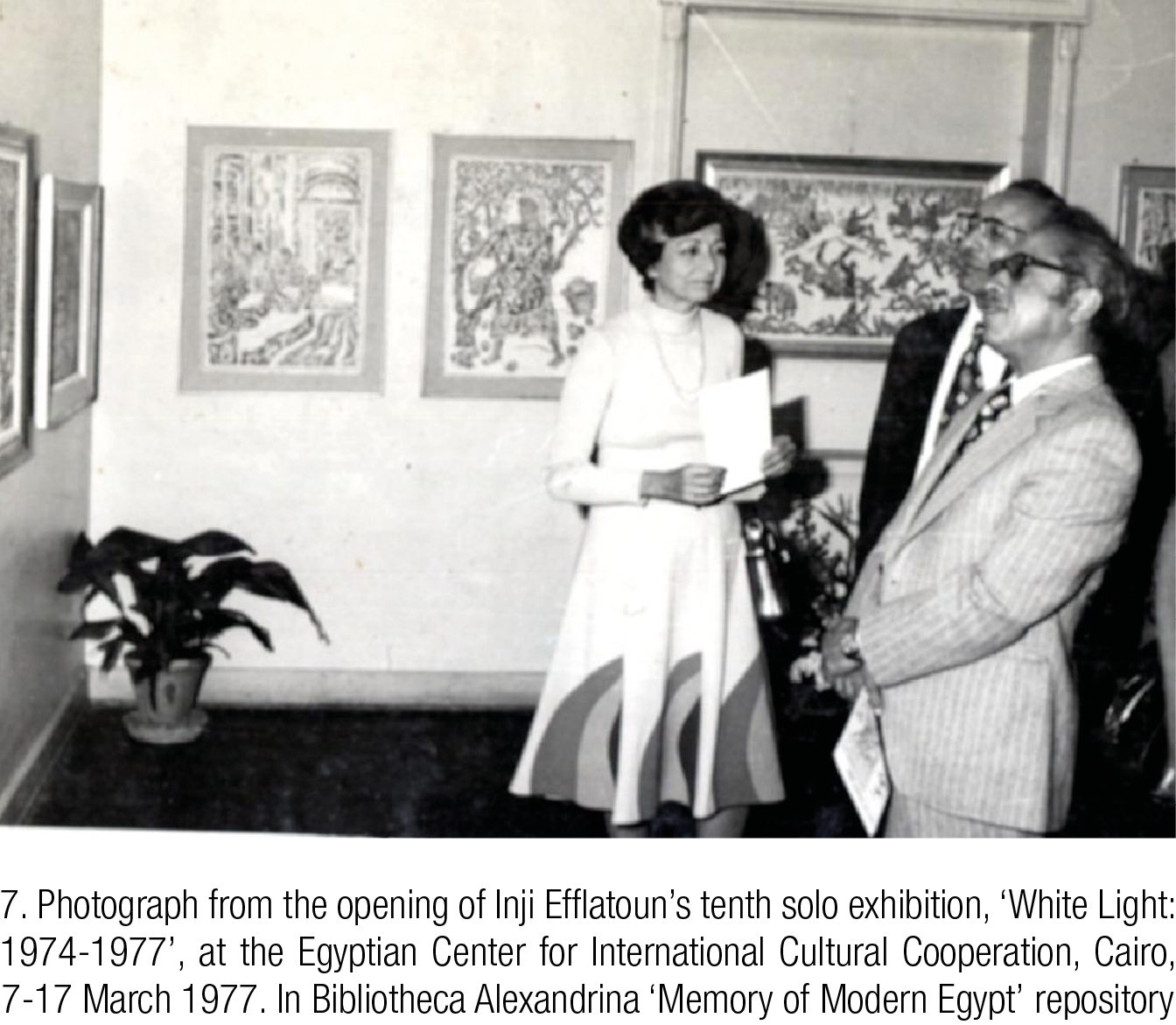

This is a frame by which I propose to consider the paintings in the major exhibition Efflatoun mounted in Cairo the following year, at her solo exhibition entitled «White Light» [7]. Containing paintings she had completed over a three-year period, it debuted work from the final phase in Efflatoun’s effort to show the interpenetration of landscapes, worker subjects, and nature as a pictorial agent. Thanks to the absence of singular, central heroes, the paintings received multiple ideological readings from Egyptian onlookers. Critic Naim Attiya lauded Efflatoun’s use of the canvas support as a participant in the process of transubstantiating labor into beauty. He designated the paintings as ritualized compositions that captured a new spirit drifting over villages as work sites, bringing political consciousness to workers in the field (Attiya, 1977). Other critics saw nationalist motifs, such as Arab writing, and the symbolic motifs of spirit-oriented Eastern aesthetics (Ali, 1977). Efflatoun herself framed the decision to expand her blank space as a way of introducing air into the picture: «This allows the painting to breathe in addition to detailing movement» (LaDuke, 1989: 484). Notably, her comments serve to displace the locus of meaning from the artist’s individual sensory apparatus to that of «the painting» as something responsive to shared work and shared space.

What would it really mean to see as a woman, or to see in solidarity with other women? Might Efflatoun have staged the conditions for just such gendered viewing? Certainly, other feminist thinkers have taken up similar questioning. The art historian Griselda Pollock, who has long been based in the United Kingdom, has reflected on the importance of the critical visual theories that came into prominence in the 1970s, reminding us that feminists in Anglophone circles in this decade came to recognize modernist painting as a discourse founded on the paradoxes and anxieties of a masculinity that hysterically figures, debases and dismembers the body of woman» (Pollock, 1988: 159). Pollock points out that feminism is necessarily alienated from major modernist narratives. In the 1970s, as a way to escape its dispossessing frame, feminists wielded Brechtian tactics of «defamiliarization» intended to liberate the viewer from the state of passively identifying with these fictional worlds. This made for an epistemological commitment to realism, sparking much feminist cultural activity in a documentary mode meant to investigate women’s lives, experience and perspectives. But equally it spurred a desire to ensure that the very processes of making experience visible would cease to uphold the already sanctioned «official» perceptions of the world.

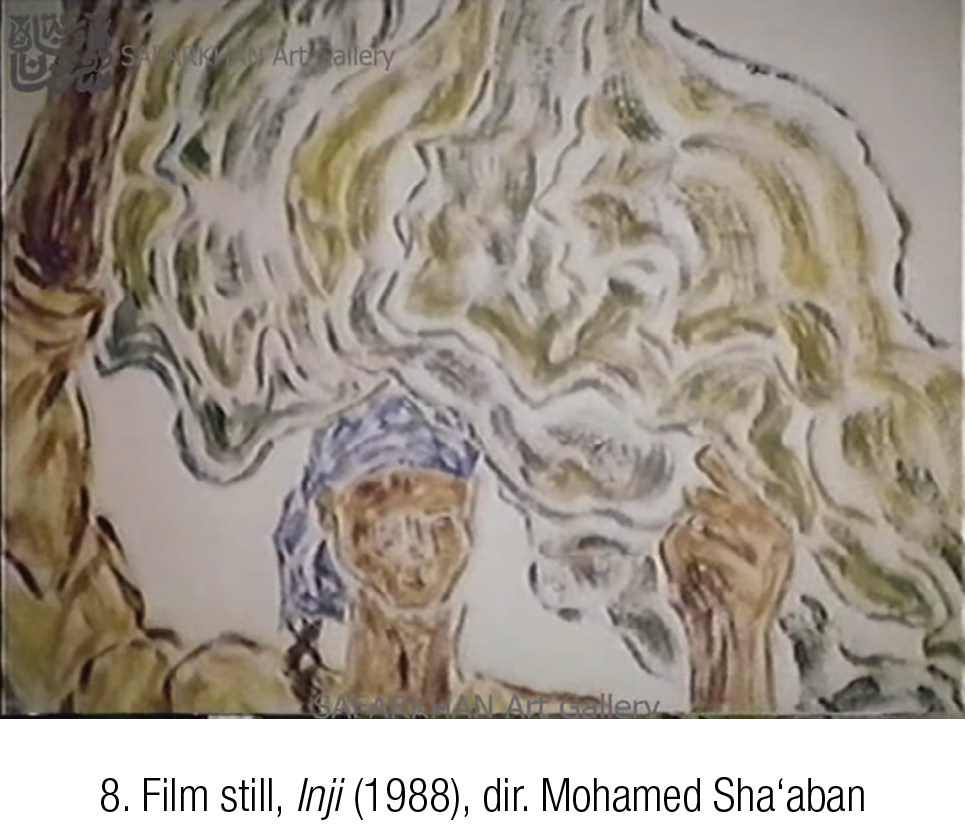

Because Efflatoun continued to work with paint until the end of her life, she can sometimes appear out of step with other artists who critiqued the inherited formats of modernist media by means of montage tactics and an aesthetics of non-unity. And yet, she too developed tactics to split and restage «reality» in the name of reclaiming space for a differently embodied community. Her archival corpus includes not only drawings and clippings but also photographs and even an experimental film documentary. The film, titled Inji and completed in 1988, delivers to viewers numerous cinematic passages of cross-cuts. Efflatoun appears in multiple facets, such that presence mixes with representation of both self and place: her interactions with peasant girls in the country, her sketches of their portrait likenesses, and her finished paintings [8]. As a result, far from delivering the kind of synthetic clarity one might expect from realist painting, the paintings appear on screen in such extreme close-up that the brushstrokes used to designate a «field» register as formal equivalents to those that register «worker.»

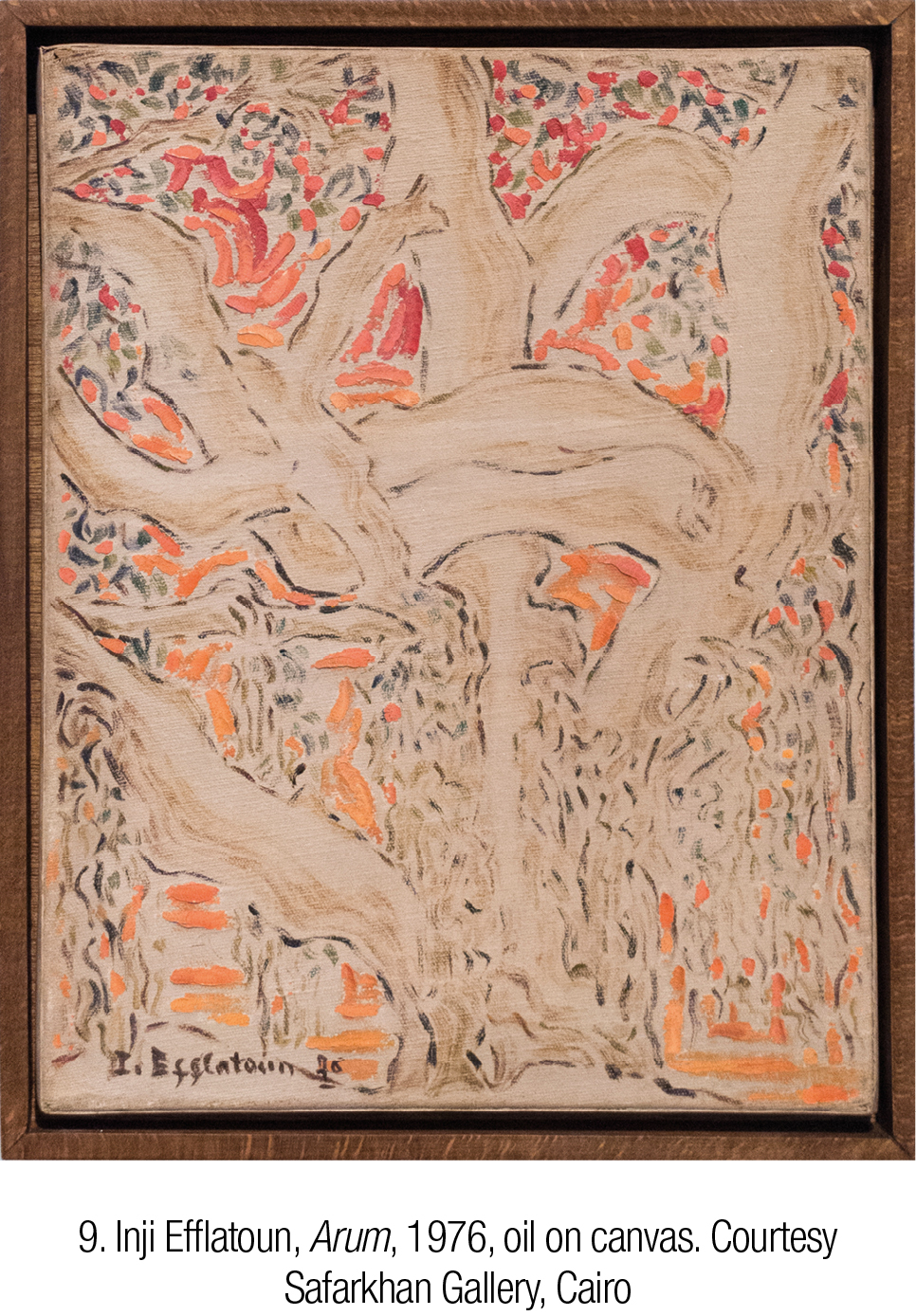

In 2015, the kaleidoscopic structures of Efflatoun’s practice received for the first time a fully contemporary viewing when curator Okwui Enwezor selected some of her paintings for that year’s Venice Biennale, under the title «All the World’s Futures.» The Venice installation paired a few of the dark prison works with a larger preponderance of «white light» – era paintings [4]. Many of the latter paintings appeared beguiling decentered in composition, including Arum (1976) – its title an Egyptian name for taro root – and its appropriately rhizomatic dashes of color [9]. The sense of needing to move one’s eyes from node to node continued even into a display case of sketches in the same room: resting on a marker drawing of an orange harvest, a watercolor of bricklayers emphasizing the tactility of color in a white void, and so on. These were arranged as facing in several directions, thereby giving the impression of participating in a still unfinished musée imaginaire. As a space to be experienced, the installation promoted an aesthetic of openness to shifts in not only vision but also movement of both rhythm and breeze. Because the whiteness of the paper support seems to chime with the empty canvas of the paintings, a viewer’s attention moves to the margins of Efflatoun’s images and begins to link each one to another.

Ultimately, I have been arguing that Efflatoun’s serial engagement with landscapes that dissolve subjects into larger frames such as «nature» and «labor» have to be understood as counterposing multiform openness against the fixed definitions of personal and national status might otherwise isolate her (and other women). As the Venice Biennale’s restaging of her particular realist practice helped to demonstrate, Efflatoun’s late works use light into a medium of interrelation. Hardly a cleansing agent or an excoriating force meant to strip away illusion, such light – in effect holding the status of a positive negative – has no role to play in the somatophobia that served to educate and discipline women. Instead, it serves as an immanent aggregator ready to incorporate bodies into alternative modes of sociality; the paintings take as their political subject the capacity of a shared optical field to encompass its ostensible objects. As such, they cede very little power to the outside viewer to claim or organize their contents. By directing the eye elsewhere, the paintings exert a destabilizing force upon the normative construction of the Egyptian national self as an upright man. Indeed, they propose the possibility of finding solidarity away from the scrutinizing gaze.