IRENE MORENO-MEDINA

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España

irene.morenom@uam.es

ORCID 0000-0002-3745-7253

CYNTHIA MARTÍNEZ-GARRIDO

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España

cynthia.martinez@uam.es

ORCID 0000-0001-7586-0628

REBECCA JANE ALLEN

Mount St. Joseph University (Cincinnati, Ohio), E.E.U.U.

rebecca.allen@msj.edu

ORCID 0000-0003-0044-2047

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

Esta obra está bajo licencia internacional Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.ABSTRACT:

It is increasingly necessary to advance towards a deeper understanding of teaching practices aimed at teaching for, in and from, democratic principles. For this reason, this research seeks to understand teachers’ conceptions of democracy in education in Spain. To this end, a phenomenographic study was carried out with 58 Spanish teachers selected according to the level of education they teach (Primary and Secondary Education) and the ownership of the school (public and private-subsidized). The data collection technique was the phenomenographic interview. The results indicate the existence of three categories of conceptions of democracy in education: i) that which refers to the participation of the agents in the school and its functioning, ii) that which considers it as the sense of belonging and emancipation of the protagonists of the educational process and, iii) that which understands it as a social responsibility of the school and its protagonists. Understanding teachers’ conceptions of democracy in education helps to move towards an education in democracy in which democratic values are taught and everyone has the opportunity to live together and participate in decision-making processes.

KEYWORDS: Democracy, Education, Teachers, Compulsory education, Conceptions.

RESUMEN:

Concepciones docentes sobre la democracia en la educación en escuelas en contextos desafiantes y favorables

Cada vez es más necesario avanzar hacia una comprensión más profunda de las prácticas docentes encaminadas a enseñar para, en y desde los principios democráticos. Por este motivo, esta investigación busca comprender las concepciones de los docentes sobre la democracia en la educación en España. Para ello, se llevó a cabo un estudio fenomenográfico con 58 profesores españoles seleccionados en función del nivel educativo que imparten (Educación Primaria y Secundaria) y la titularidad del centro (público y privado subvencionado). La técnica de recolección de datos fue la entrevista fenomenográfica. Los resultados indican la existencia de tres categorías de concepciones de la democracia en educación: i) la que se refiere a la participación de los agentes en la escuela y su funcionamiento, ii) la que la considera como el sentido de pertenencia y emancipación de los protagonistas de la escuela. el proceso educativo y, iii) el que lo entiende como una responsabilidad social de la escuela y sus protagonistas. Comprender las concepciones de los docentes sobre la democracia en la educación ayuda a avanzar hacia una educación en democracia en la que se enseñen valores democráticos y todos tengan la oportunidad de vivir juntos y participar en los procesos de toma de decisiones.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Democracia, Educación, Profesorado, Educación obligatoria, Concepciones.

1. INTRODUCTION

Research on teachers’ conceptions is an emerging line of research that allows us to understand how certain phenomenological conditions shapes the way in which individuals act, their expectations, and the specific value that this phenomenon has for them individually (Griffiths et al., 2006; Prieto & Contreras, 2008). Within educational research, teachers’ conceptions of different areas of knowledge have been studied—for instance, the conceptions of the teaching-learning process, evaluation of the cognitive processes of the students.

One of the aspects still little researched the implicit ideas of teachers about democracy in education are—that is, delving into the governance, organization, decision making and consensus building both in the school and with the larger educational environment (Landwehr & Steiner, 2017). Despite the social acceptance of democracy as a concept, democracy has been conceptualized in varying ways. For example, it has been considered from “the best hope in the world” by Thomas Jefferson to the “worst form of government” by Winston Churchill (Flanagan et al., 2005, p. 193).

Thus, conceptualizing democracy is not an easy task. Far from being a static concept, it is possible to define it as a continuum that goes from its finest approaches to its thickest. It is the so-called thick-thin spectrum established by Carr (2008). A “thin” conception of democracy refers to a conception of democracy as representative rather than participatory that places special value on candidate selection processes, representation, and voting. On the other hand, the “thick” conception of democracy refers to promoting individual participation in society and, furthermore, holding that this participation is critical.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The study of conceptions of educational democracy in an emergent line of work that delves into the voice of its different actors to understand how they conceive democracy in the educational field. In fact, Carr (2008) as a reference in this line of research explored more than a decade ago how educational systems can foster a deeper and more meaningful democratic experience by distinguishing between “thin” democracy, which focuses on electoral and representative processes, and “thick” democracy, which emphasizes critical participation and social justice. His research with education students in the United States reveals a tendency to understand democracy superficially but also highlights the potential for educators to teach a more profound form of democracy that considers power and social differences. Subsequently, Carr et al. (2018) investigate the conceptualization and practice of democracy in education through a comparative study in Canada, the United States, and Australia, involving over 1,000 participants. This report emphasizes the need for education that promotes deep democratic participation and social justice, highlighting the importance of power relations in the educational context. The findings suggest that achieving true democratic education requires fostering political literacy and transformative education, enabling students to engage actively and critically in society. Ginocchio et al. (2015) and Vidal et al. (2019) have used Carr’s conceptualization to study teacher perceptions whereas Long (2018) studied school principles. Student perspectives have been covered by Mathe (2016) and Quaranta (2020). Using the same Carr thick-thin conceptualization, other studies have explored pre-service teachers’ conceptualizations of democracy (Carr et al., 2018; Hung & Perez, 2020; Martinez-Garrido et al., 2022; Zyngier, 2016). Studies have also looked at combined student-teacher perspectives (Belavi et al., 2022) or students and teachers in different contexts (Moreno-Medina, 2022; Moreno-Medina et al., 2022).

Fundamentally, the results obtained in the studies that conceptualize democracy in education by teachers refer to three main conceptions of teachers about democracy in education: elitist, representative, and participatory. Teachers who conceive democracy as elitist consider that a small group of individuals within the school are those who hold positions of power that directly and that group orchestrates establishment of hierarchical relationships amongst the members of the educational society. For those who understand democracy as representative, democracy refers to representation in collegiate bodies. Teachers who have a participatory conception of democracy consider that the active and critical participation of the members of the educational community is an indisputable component in education (Belavi et al., 2021). With regards to the students, results from studies with students show the uncertainties students in the face of a concept of such complexity. Some students hold a more liberal understandings of democracy viewing democracy as carrying out voting; other students are undecided as to whether as individuals can exercise self-government (Arensmeier, 2020; Mathe, 2016).

In summary, studies cover the spectrum of the perspectives on educational democracy of many different stakeholders. These implicit representations of the context may have not been consciously contemplated, by rather determined by the circumstances and contexts. The exploration of these conceptions is particularly important in the learning process, since teachers reflect their underlying implicit assumptions in their professional practice (Álvez & Pozo, 2014).

However, even though stakeholder perspectives are relatively well covered, there are not so many studies that touch on the social and economic context that surrounds the schools, with the school environment being a determining factor in the implicit ideas of teachers (Murillo et al., 2016). Thus, given that the social and cultural context of schools may be a key factor in conception of democracy in education, the present study seeks to understand the teacher conceptions of democracy in schools with both challenging and favorable socio-economic conditions. This broader understanding of educational democracy in diverse contexts will contribute to building educational democracy in these contexts (Domínguez, 2010).

3. METHOD

Because of our research objectives, we carried out a phenomenological study—phenomenology allowed us to delve into the conceptions that people have about a specific phenomenon based on their own thoughts and experiences. (Bowden & Walsh, 2000; Marton, 1986). Moreover, phenomenology allowed us to analyze conceptions which vary among people who experience a phenomenon (Murillo et al., 2022).

The methodological design of the phenomenological study required that the categories be a posteriori, that is, that they arise from the interviews carried out with the teachers. Open coding is performed to analyze the teacher interview data. Thanks to this emerging design, it is possible to explain teachers’ conceptions of democracy in education without duplicating theoretical models (Creswell, 2005).

The study participants were 58 teachers from public and private schools. There were 30 schools; 15 of the schools were in favorable contexts and the other 15 in schools in challenging contexts. The participant recruitment these was carried out by non-probabilistic sampling by quotas. Namely, participants were selected from different cycles and subjects, as well as from challenging and more resources schools, and finally from both private and public schools.

Data collection was conducted through phenomenological interviews in which two generating questions were used— “What is democracy for you?”, and “What is democracy in education for you?”. These main questions were followed up with additional open questions that helped the interviewees expound upon their answers. To enhance the interview process, we incorporated a diverse array of questions that encourage thoughtful responses while maintaining a concise duration. By diversifying the questions, interviewees can delve deeper into various aspects of the topic while still fostering spontaneity. Additionally, offering open-ended questions allows individuals to express themselves freely without feeling constrained by the interview format. This approach fosters genuine dialogue and prevents the interview from feeling overly scripted or rigid. Furthermore, providing opportunities for follow-up questions based on the interviewee’s responses can lead to richer discussions and insights. Overall, promoting a balance between structure and flexibility can optimize the interview experience for both interviewers and participants. The interviews were conducted face-to-face and via online video conferencing. For interviews that could be carried out in person, quiet places were reserved for the teachers to feel comfortable in order to express themselves and develop their answers freely. The interviews were anonymized using a code, in the following order: a) number (number corresponding to the order of the interview); b) D for teacher; c) Prim or Sec (Prim for Primary teacher and Sec for high school teacher); d) Pub or Priv (Pub for Public school and Priv for Private School); d) Des or Fav (Des for Challenging context and Fav for Favourable context in a socioeconomically way).

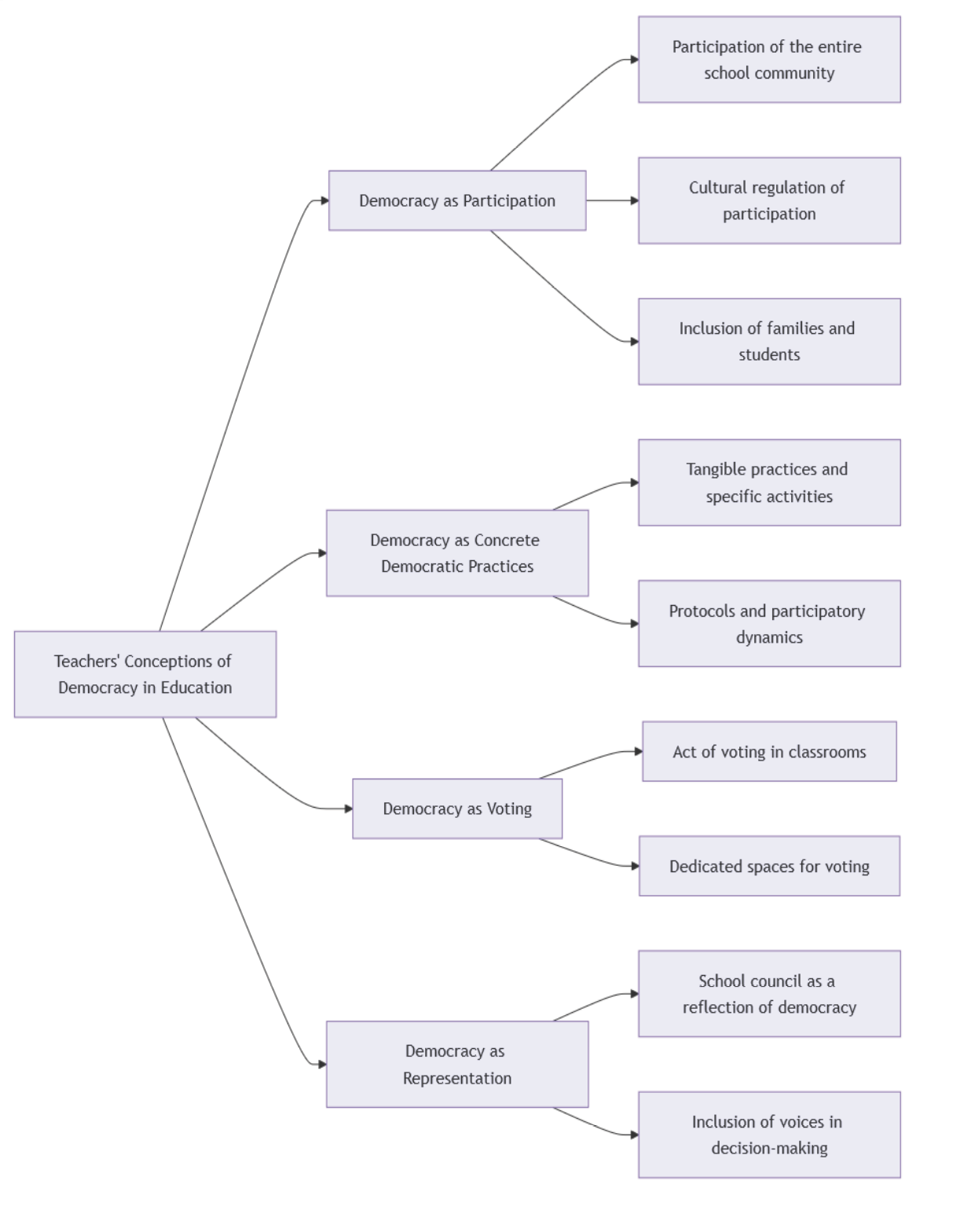

During the data analysis, the criterion of proximity to the teachers’ discourse was assumed. Therefore, the categories of analysis were not defined a priori, but a posteriori; quotes from the participants referring to their conception of democracy in the schools were categorized and coded (Figure 1). Following the initial categorization, subsequent readings were conducted to further classify them into subgroups. This process facilitated the development of reliable and representative categories and subcategories derived from the participants’ discourse. It’s crucial to perceive these categories and subcategories not as fixed concepts, but rather as different points along a continuum. From these first categories, more general groups arose for the appointments that had in common conceptions of democracy in the educational center and a tree of meaning was elaborated that allowed explaining the conceptions of the participating teachers.

To increase validity, the results are based on the internal logic and relationships of the data. To ensure confirmability, the researchers adequately applied the necessary procedures for data collection and the analysis process.

Figure 1. Vector presentation of category analysis. Source: own elaboration

The study followed the guidelines of the Code of Good Research Practice drawn up by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. All the teachers were first informed about the topic and objectives of the research. Before starting the interviews, we asked for their consent to have them recorded. The names of the volunteer participants and their educational centers do not appear in any case in the study, since the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed.

4. FINDINGS

Spanish school teachers’ conceptions about democracy are organized into different categories and subcategories. During the interviews, teachers often referred to their own experiences, turning the answer into something tangible for themselves, which facilitated the development of their ideas. Based on these contextualized approaches, teachers’ conceptions have been grouped into four large categories around what democracy in education is for them.

4.1. Democracy as participation

The results show that a large part of the teachers who work in either challenging or favorable schools in feel that democracy in education necessarily must cross the walls of the school classrooms and reach the surrounding neighborhood that surrounds them. For these teachers, democracy in education must be born in the entire school community. Teachers believe that democracy must permeate the entire educational community—the school leadership, teachers, students, families and even neighborhood institutions. Although teachers from favorable and unfavorable contexts emphasized democracy in the neighborhood, teachers from unfavorable contexts emphasized this idea the most strongly.

For teachers, democracy in education must be a collective project in which everyone can participate, and have a voice and a role; however, participation in the process can be regulated in certain ways. This regulation does not mean that participation in democracy is compulsory, but rather that the procedure is culturally established, without necessarily having to be written in a project or plan. Democracy needs to be centric to the culture. This is how a school teacher in an unfavorable context put it:

Well, for me, democracy in schools takes into account all of us who participate. But, of course, we need to regulate that participation because, as I said before, families have an important role, but they cannot participate in the whole process, just like the students—they participate in some parts of the teaching and learning process. (3_D_Prim_Priv_Des)

On the other hand, in this conception of democracy, the school community as a whole has always been incorporated into the definition. The teachers are aware that, due to their professional commitment, the leadership team and the teaching team will focus participation on the schools themselves, however, participation has to go further and not remain with professional roles. Participation must be inclusive, and students and families must be part of these democratic processes.

Another teacher from a different school explains the idea that:

I think that one of the most important things is the different groups participating, both the teachers, the students, the AMPA, ... In short, that the different groups can exercise their democratic rights. Like being able to comment on the things that are done at school and being able to participate freely. It is also important to have a critical attitude, as one of the values. The act of participating in this way is also an example within schools. That is to say, what is taught at a theoretical level is one thing, but at the same time democracy is an eminently practical fact, which needs to be developed in all of the classes. (6_D_Sec_Priv_ Des)

Another teacher indicated the same thing, but referred to a process that he considers democratic and that has already started in his school:

For 3 years, we have had management commissions, and that these commissions are made up of teachers, families and members of the leadership team, and everyone works as equal partners, so dynamics are established that have an assembly participation nature. We want am openness and transparency in participation and the expression of needs, of freedoms that are based on responsibility and on the value, that comes backs to the school later. (1_D_Pri_Priv_Des)

The conception of democracy is also seen in some of the teachers that work in schools in more favorable contexts.

Greater involvement of families, I think. Greater participation, that the voice of the workers is listened to more, [and more listening] to teachers in the areas that later go to school leadership. (17_D_Sec_Priv_Fav)

Well, for me, democracy in the school is that important and less important decisions too will be made taking into with parents, students, teachers, and leadership working at the same level. (4_D_Prim_Pub_Fav)

The conception of democracy as participation has different nuances as soon as teachers begin to develop what participation is for them. One of these nuances is delegation. Some teachers consider that this participation must come from delegation that not only allows participation, but also to which the delegation is also added. A second teacher from an unfavorable context explains that to participate you have to delegate, and that, therefore, democracy in education, intrinsically, encompasses delegation and distribution of responsibility and participation. Here is the teacher’s explanation:

I think democracy is delegating... Delegation... Delegating something, letting them participate and they [participants] will see the responsibility within their own participation. In the end, it [such participation] is a bit the purpose of learning…in the end we all learn from being wrong or from having made our own decision...And you know that... well... Sometimes the consequence is not the most positive, but you yourself have made the decision. (2_D_Pri_Priv_Des)

Likewise, another teacher recalls that participation is truly democratic when everyone, regardless of their circumstances, beliefs, or status, has equal opportunity to participate.

Somehow, all kinds of students need to have a place in the school. That does not mean that they are all together in the same school, because it may not be feasible. But it does mean that the educational system gives opportunities to absolutely everyone; no matter what circumstances you have, what race you have, what ideology you have, and so on. I believe that this is a fundamental principle that needs to be in place. (1_D_Sec_Priv_Fav)

4.2. Democracy as concrete democratic practices

Some school teachers in challenging contexts directly associate their conception of educational democracy with concrete, tangible democratic practices; that is, practices in which they feel that democracy is something that is celebrated and of which they are a part. Not all of these conceptions are along these lines, but they are useful to understand how teachers from challenging centers conceive democracy in education. These practices, for the most part, are related to participation as they understand it, but the nuance is found in the practical form. associate democracy at school with specific activities and tasks While in the first category we find teachers who express their idea by mixing representation with participation, in this second conception teachers relate democracy to concrete activities. The first participant explains that democracy in education is to establish dynamics of participation and that these are regulated with a specific set time, with a distribution of tasks, and that participation forms part of the institutional culture of the center. That is, that democracy in education are processes that are carried out because the practices have been institutionalized:

It is evident that establishing participatory dynamics requires additional time and scheduling more meetings, as individuals need time to express themselves. If we aim for that, the focus of the meeting will be collective, ensuring active participation. Through this participation, a series of consensus-based agreements will emerge, reflecting the collaborative effort put forth by all participants. Subsequently, ongoing monitoring and follow-up will be conducted collectively. This is the proposed framework: within the center’s structure, teams at each level, including tutor teams, are managed through explicitly defined competencies and task distribution. Ensuring equitable participation is crucial, and the teams themselves contribute to this equitable distribution. However, the overall structural framework is determined by the management team. If the management team upholds this working vision, it will be developed accordingly. (1_D_Pri_Priv_Des)

Other teachers from disadvantaged contexts refer to democracy in education being shaped by various protocols created beforehand by the group of teachers at the school. Furthermore, these protocols can be modified each academic year. The protocols they mention include the school’s action plan, internal regulations, and the coexistence plan. For these teachers, being part of this set of protocols is seen as a democratic practice and aligns with their conception of democracy in the school. One teacher explains it as follows:

Here, all documents are collectively created by everyone involved. For instance, the internal regulations, coexistence plan, and diversity action plan are the result of collaborative efforts… All these documents are not imposed by the management team; rather, we invest time in collaborative work with coordinators from all stages of education. They, in turn, disseminate the information to the teachers within their respective stages, who further share it with the rest of the teaching staff. This process resembles a hierarchical structure where information flows from one level to another…. our organization operates in a horizontal manner, where there is no sense of the principal being the one in control. While the role of the principle is necessary for legal reasons, it is true that we are quite horizontal in structure, and we pay attention to all the contingents. (3_D_Pri_Priv_Des)

4.3. Democracy as voting

It is worth noting that teachers from more favorable contexts tend to associate democracy in education closely with the act of voting. While voting is indeed a form of participation, in these cases, it is specifically referred to as a manifestation of democracy. Teachers who hold this perspective also associate it with a more closed and private approach. In fact, they express this notion by emphasizing its implementation within their own classrooms. One teacher provides an example of how it is carried out in their school:

Once a week, the children gather in an English class, where they have the opportunity to discuss the issues they observe in the school and express what changes they would like to see, and there they can vote. They showcase their talents once a month. (2_D_Pri_Priv_Fav)

Another teacher refers to this idea and emphasizes the need for dedicated spaces that enable voting for the various members of the educational community:

It [the objective] would to attain within the school, those spaces and moments in which students, teachers, and families can express themselves, participate, and vote on topics that affect us, the entire educational community. (1_D_Prim_Pub_Fav)

In this conception, the teaching staff makes a special reference to allowing students to make decisions in school, but there is a nuance to this decision-making process: the imposed limits. This implies that, with voting, this conception of democracy in education is very limited; it is mainly applied to students, and voting is only held for certain specific and previously teacher-established established matters. These matters are those that directly affect the students, but not all of them are considered. A clear example is holding a vote to choose the date of an exam, where only the day is decided, but not the type of assessment, the location, or the topics. In the following lines, a teacher explains their conception of democracy in education:

I believe that aside from voting on things like the date of an exam or other preferences, what the majority wants…Generally [the majority] will be listened to most of the time. But whenever I see Students face to face, I ask them what’s going on. ‘I don’t like this, or I don’t like that, this looks good to me, or this looks bad to be’. I listen to them too a lot, more than just the people who voted for certain things. (8_D_Pri_Priv_Fav)

4.4. Democracy as representation: the school council

In this section, the main conclusions of the study will be offered, based on the data obtained and the discussion carried out.

We have the school council, which operates somewhat democratically. All groups within the educational community are represented, and it is in this forum where issues are raised, possible actions are proposed, and approvals are sought. In other words, this is where I perceive a greater reflection of democracy, while within the classroom it tends to be more anecdotal. When it comes to children, the focus is a bit more on educating them and teaching them about democracy. Subsequently, within the school, it is the governing body that fully embodies this democratic spirit is the council. (8_D_Pri_Priv_Fav)

In the following quote, the interviewee refers to the main reason why they feel that democracy in education is based on the reference of the collegiate body for the school.

The school council, which is a space for participation where different members of the educational community are represented, including students, teachers, school administration, and families, allows the voice of each party to be included in larger decision-making processes. (12_D_Pri_Priv_Fav)

Another teacher highlights the fundamental role of families in the school council, even if their requests are not carried out, but simply by granting them a space in which they can express and submit their requests, a consensus can be reached.

The school council ultimately represents parents who should have something to say, or at least contribute. Consensus will be reached eventually. Some contributions may be implemented or not based on the consensus reached within this democratic process. The important aspect is that they are listened to and taken into account. (17_D_Pri_Pub_Fav)

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study suggest four conceptions of democracy in education that, with nuances, align and complement previous works, such as Carr’s (2008) study. Delving into whether there are differences in conceptions based on the school context, teachers working in favorable contexts conceive democracy in education as a voting process (Mathé, 2019) or have a technocratic view of it, such as that of the school council and its representatives (Zyngier, 2016). In other words, the idea of representative democracy or classical direct democracy (Rodríguez Burgos, 2015) emerges in the study’s results when teachers from favorable contexts express that voting is their main concept of democracy in education. However, teachers in disadvantaged contexts refer to family involvement as their conception of democracy in education (Harris, 2009). Furthermore, the results indicate that these teachers have a concept of democracy in education that emphasizes the participation of other community members. This aligns with the views expressed by Sáenz López & Rodríguez Burgosa (2010), who advocate for a participatory concept of education where the school requires the involvement of all educational institutions, shared responsibility, or participatory democracy.

One of the strengths of this research is the number of participants: 30 teachers from both public and private educational centers in schools located in favorable and challenging contexts agreed to be interviewed. Because of this, it was possible to examine the different conceptions of democracy in education according to the school context. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of research on conceptions of democracy in education, building upon previous studies that have emerged in recent years.

In addition to the findings presented, the study encountered some difficulties due to the respondents’ vague responses, making it challenging to provide a concrete definition of democracy in education. It appears that many teachers do not have a clear conception of what democracy is, but we understand that this reflects the reality of teachers. Furthermore, it can be observed that there are differences among teachers depending on the context in which their schools are situated. This is a clear indicator that the context not only influences the dynamics of the school but also the implicit ideas that teachers hold about democracy in education.

The results of this research, along with its strengths and limitations, pave the way for future studies. Future directions could include complementing this study with another aimed at exploring the democratic practices that take place in schools and whether the school context influences their variations. Another potential study could focus on expanding the understanding of families’ conceptions of democracy in education, as they are one of the stakeholders mentioned by teachers.

This study highlights the importance of delving into teachers’ conceptions of democracy in education, not only to comprehend their implicit ideas but also because these ideas directly impact their practice. Transforming education requires being aware of the ideas that influence teaching tasks and, as a result, striving for more participatory, equitable, and just conceptions and practices.

6. FUNDINGS

This article has been developed within the framework of the research project funded by the State R&D&i Plan of the Government of Spain, titled “Democracy in Schools as the Foundation for Education for Social Justice” (Ref. EDU2017-82688-P).

Irene Moreno-Medina thanks the postdoctoral fellowship of Margarita Salas for young PhD (CA4/RSUE/2022-00208), financed by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades of the Government of Spain.

REFERENCES

Alves, I. P. &, Pozo, J. I. (2014). Las concepciones implícitas de los profesores universitarios sobre los requisitos para el aprendizaje. Revista da FAEEBA-Educação e Contemporaneidade, 23(41), 191-203. https://doi.org/10.21879/faeeba2358-0194.v23.n41.836

Arensmeier, C. (2010). The democratic common sense. Young Swedes’ understanding of democracy - theoretical features and educational incentives. Young, 18(2), 197-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/110330881001800205

Belavi, G., Flores, C., Guiral, C. &, Türk, Y. (2021). La democracia en los centros educativos españoles: Concepciones de docentes y estudiantes. Revista Fuentes, 23, 244-253. https://doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2021.15375

Bowden, J. &, Walsh, E. (2000). Phenomenography. RMIT University Press.

Carr, P. R. (2008). Educadores y educación para la democracia: Trascendiendo una democracia «delgada». Revista Interamericana de Educación para la Democracia, 1, 146-166.

Carr, P. R., Thésée, G., Zyngier, D. &, Porfilio, B. J. (2018). Democracy, political literacy and transformative education (Informe final). Universidad de Québec.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Prentice-Ha-ll.

Domínguez, J. (2010). Democracia, educación y escuela. Foro Social de Madrid

Flanagan, C., Gallay, L., Gill, S., Gallay, E. &, Nti, N. (2005). What does democracy mean? Correlates of adolescents’ views. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(2), 193-218.

Ginocchio, L., Frisancho, S. &, Rosa, M. I. L. (2015). Concepciones y creencias docentes sobre la democracia en el colegio. Revista Peruana de Investigación Educativa, 7(7), 5-29. https://doi.org/10.34236/rpie.v7i7.48

Griffiths, T., Gore, J. &, Ladwig, J. (2006, noviembre). Teachers’ fundamental beliefs, commitment to reform, and the quality of pedagogy. [Comunicación]. Australian Association for Research in Education Conference, Adelaide, Australia.

Guiral, C. &, Ortega, A. (2021). Educación a través de la democracia. Revista Educación, Política y Sociedad, 6(2), 209-227. https://doi.org/10.15366/reps2021.6.2.008

Harris, A. (2009). Equity and diversity: building community. Improving schools in challenging circumstances. Institute of Education, University of London.

Hung, Y. H. &, Perez, N. (2020). Exploration of immigrant in-service and pre-service teachers’ conception and practice of citizenship in the United States. Citizenship Teaching & Learning, 15(1), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.1386/ctl_00022_1

Jurado de los Santos, P., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., Marín-Marín, J. A. &, Soler Costa, R. (2020). The Term Equity in Education: A Literature Review with Scientific Mapping in Web of Science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3526. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103526

Landwehr, C. &, Steiner, N. D. (2017). Where Democrats Disagree: Citizens’ Normative Conceptions of Democracy. Political Studies, 65(4), 786-804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717715398

Long, J. (2018). Educational administrators’ perspectives of democracy and citizenship education: interviews with educational leaders. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 13(2), 2-20. https://doi.org/10.20355/jcie29349

López-Belmonte, J., Marín-Marín, J., Soler-Costa, R. &, Moreno-Guerrero, A. (2020). Arduino Advances in Web of Science. A Scientific Mapping of Literary Production. IEEE Access, 8, 128674-128682. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.3008572

Martínez-Garrido, C., Hidalgo, N., Márquez, C. &, Graña, R. (2022). Las concepciones docentes sobre democracia en educación en España. Un estudio fenomenográfico. Aula Abierta, 51(3), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.51.3.2022.293-302

Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography—a research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. Journalofthought, 28-49.

Mathé, N. E. H. (2016). Students’ Understanding of the Concept of Democracy and Implications for Teacher Education in Social Studies. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(2), 271-289. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.2437

Moreno-Medina, I. (2022). Democracia en la escuela: concepciones de estudiantes de contextos desafiantes y favorables. Revista Lusófona de educação, 58, 89-103, https://doi.org/10.24140/issn.1645-7250.rle58.05

Moreno-Medina, I., Martínez-Garrido, C., Hidalgo, N., &, Oliver, R. G. (2022). Concepciones de docentes de escuelas en contextos desafiantes y favorables sobre democracia en educación. In M. P. Cáceres Reche, J. A. López Núñez, S. M. Arias Romero &, M. Navas-Parejo (coords), Análisis sobre metodologías activas y TIC (pp. 342-352). Dykinson.

Murillo, F. J., Hidalgo, N. &, Flores, S. (2016). Incidencia del contexto socio-económico en las concepciones docentes sobre evaluación. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 20(3), 251-281.

Murillo, F. J., Hidalgo, N. &, Martínez-Garrido, C. (2022). El método fenomenográfico en la investigación educativa. RiiTE Revista interuniversitaria de investigación en Tecnología Educativa,13,117-137. https://doi.org/10.6018/riite.549541

Prieto, M. &, Contreras, G. (2008). Las concepciones que orientan las prácticas evaluativas de los profesores: un problema a develar. Estudios Pedagógicos, 34(2), 245-262.

Quaranta, M. (2020). What makes up democracy? Meanings of democracy and their correlates among adolescents in 38 countries. Acta Politica, 55(4), 515-537. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-019-00129-4

Rodríguez Burgos, K. (2015). Democracia y tipos de democracia. En X. Arango & A. Hernández (Eds.), Ciencia política, perspectiva multidisciplinaria (pp. 49-66). UANL.

Sáenz López, K. &, Rodríguez Burgos, K. (2010). La promoción de la participación ciudadana. In M. Estrada Camargo &, K. Sáenz López (Coords.) Elecciones, gobierno y gobernabilidad (pp. 189-213). Instituto Federal Electoral.

Vidal, R., Raga, L. &, Martín, R. (2019). Percepciones sobre la escuela democrática en Argentina y España. Educação e Pesquisa, 45. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634201945188681

Zyngier, D. (2016). What future teachers believe about democracy and why it is important. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 782-804. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1185817