M. DEL MAR BADIA MARTÍN

Department of Basic, Developmental and Educational Psychology, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain

mar.badia@uab.cat

ORCID 0000-0001-7923-6267

ROSA FORTUNY GUASCH

Department of Applied Pedagogy, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain

rosa.fortuny@uab.cat

ORCID 0000-0001-5279-3821

HONGAN ZHOU

College of Educational Science, Sichuan Normal University, China

honganzhou@163.com

ORCID 0000-0003-2873-6952

ERHUO GU

College of Educational Science, Sichuan Normal University, China

geh1@163.com

ORCID 0000-0003-2873-6952

RESUMEN:

Perspectivas comparativas de las partes interesadas sobre la educación inclusiva en cuatro regiones de China

El proyecto europeo INCLUTE (Promoción de la educación inclusiva a través del desarrollo curricular y la formación de docentes en China) Unión Europea (Proyecto Erasmus +) 561.600-EPP-1-2015-CN-EP ayuda a contribuir a la demanda de docentes altamente calificados en la escuela primaria donde se puede abordar el nivel y se puede alentar a las universidades en China a tomar en consideración los estándares europeos. Este proyecto es innovador porque se centra en el tema de la educación inclusiva para apoyar la formación de docentes de escuelas primarias chinas. El ideal pedagógico confuciano de “aprender sin discriminación” todavía predomina entre los educadores chinos en la actualidad. Sin embargo, durante los últimos treinta años, los actores gubernamentales han subrayado la necesidad de implementar políticas de educación inclusiva, siguiendo el modelo occidental. Por lo tanto, el sistema educativo chino ha comenzado a implementar la política de “aprendizaje en el aula”, una alternativa a medio camino entre la pedagogía tradicional confuciana y las nociones occidentales de educación inclusiva. No obstante, se sabe poco sobre las perspectivas y expectativas chinas sobre la educación inclusiva. En consecuencia, el presente estudio tiene como objetivo identificar la percepción de las partes interesadas chinas sobre la educación inclusiva a través de una encuesta, una entrevista y un grupo focal de una muestra de 8.412 sujetos compuestos por maestros de escuela primaria, funcionarios gubernamentales y trabajadores de organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) de Guanxi, Sichuan, Chongqing y Tíbet. Los resultados de este estudio sugieren que los actores educativos chinos conceptualizan la educación inclusiva como una idea filosófica relacionada con nuevas estrategias metodológicas, pero que no está asociada a las discapacidades, la educación para todos o la comunidad educativa. Se discuten las debilidades y fortalezas de la educación inclusiva.

PALABRAS CLAVE: AEducación Inclusiva, Enseñanza sin Discriminación, Aprendizaje en el Aula Regular, educación especial, alumnos con discapacidad.

ABSTRACT:

The European project INCLUTE (Promoting inclusive education through curriculum development and teacher education in China) European Union (Proyecto Erasmus +) 561.600-EPP-1-2015-CN-EP helps to contribute the demand for highly educated teachers at the primary school level can be tackled, and universities in China can be encouraged to take European standards into consideration. This project is innovative because it focuses on the topic of inclusive education for supporting teacher training for Chinese primary school teachers. The Confucian pedagogical ideal of “learning without discrimination” still predominates among Chinese educators nowadays. However, over the last thirty years, government stakeholders have underscored the need to implement inclusive education policies, following the Western model. Thus, the Chinese educational system has started to implement the “learning in the classroom” policy – a halfway alternative between Confucian traditional pedagogy and the Western notions of inclusive education. Nonetheless, little is known about the Chinese perspectives on, and expectations about, inclusive education. Accordingly, the present study aims to identify the Chinese stakeholders’ perception of inclusive education through a survey, an interview and a focus group out of a sample of 8,412 subjects composed of primary school teachers, government officials and Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) workers from Guanxi, Sichuan, Chongqing and Tibet. The results of this study suggest that Chinese education stakeholders conceptualize inclusive education as a philosophical idea related to new methodological strategies, but that it is not associated with disabilities, education for all or the educational community. The weaknesses and strengths of inclusive education are discussed.

KEYWORDS: Cooperative Learning, Higher Education, Teacher Competencies, Teacher Education.

1. Introducción

The concept of inclusive education has been largely debated and developed in the West. Inclusive education is a process aimed at responding to student diversity, increasing their participation both at the school’s cultural and community level, reducing exclusion in and from education, and creating flexible curricula. There are several studies that speak of its definition. For instance, Ainscow, Booth & Dyson (2006, pp. 27); Kavale & Forness (2000); Allan & Slee (2008, pp. 27-41). For Kozleski et al. (2009) claim that the basic principle of inclusive education and inclusive schools is a commitment to fostering the sense of belonging, and nurturing and educating all students regardless of their differences in ability, culture, gender, language, class and ethnicity (Kozleski, Artiles, Waitoller, 2011). In many affluent Western democracies inclusive education refers to the policy of merging well-resourced segregated special education and general education into one system (Artiles & Dyson, 2005; Singh, 2009).

In China, inclusive education is an international educational trend that emerged in 1990, during the educational reform. However, some scholars consider that the Confucian tenet of “teaching without discrimination” reflects the spirit of “inclusive education,” as a new educational thought and trend, implying the understanding and the practice of “inclusive education” which have followed a particular development process in China.

1.1. The concept of inclusive education in China: from the Confucian tenet of “teaching without discrimination” to “learning in the regular classroom”

Confucius, the educator of China during the Chinese Spring and Autumn Period (551 BC-479 BC), put forward the idea of “Teaching without discrimination” (Yang, 1980, p 170), which reflected the equality of (1) educational objects, (2) educational processes and (3) teacher-student relationships.

Li (2009) analysed the similarities and differences between “inclusive education” and “Teaching without discrimination.” On the one hand, the observed similarities are: a resemblance of theoretical assumptions; a democratic and egalitarian view of human rights and education; the similar core concept of communication; the aim of meeting the different learning needs of all; the educational function of reconstruction (unclear); and the promotion of the common development of individualization and socialization. On the other hand, some differences are that “inclusive education” pursues the development of democratic and egalitarian ideas in all human beings, with the aim of building an inclusive society. Inclusive education is increasingly integrated into the “Education For All” concept and lifelong education, and it shows an all – encompassing breadth in educational content, while “Teaching without discrimination” pursues the development of both the virtuous and the talented “shi” and “gentlemen” to govern the country. Furthermore, it emphasises social personnel, that is, knowledge of social, historical and political matters, ethics and literature, as well as a contempt for technology and productive labour. Teaching without discrimination aims to achieve peace and prosperity in the society, but women and slaves —who are at the bottom of the social scale— are excluded.

It is evident, then, that the Confucian principles of educational equality, namely “Teaching without discrimination,” shed some light on the concept of “inclusive education” current era, even though there are differences.

In fact, the first article that introduces the concept of “inclusive education” in China was published by Huang (2001). Since then, “inclusive education” has become a hot topic for university teachers and graduate students who are mainly engaged in comparative education and special education research and study, but the scholars who can conduct basic research work from basic concepts, historical logic development and education policy are very few. Huang (2004a, b) defines “inclusive education” as a new educational concept and a continuous educational process that accepts all students, opposes discrimination and exclusion, promotes active participation, focuses on collective cooperation, meets different needs and establishes an inclusive society.

Due to the fact that Huang’s interpretation is just an academic study which has not been widely accepted because the majority of Chinese scholars think the concept is vague, and inclusion’s connotation and extension are not clear, it is difficult to provide a clear and operational guidance for educational practice. For this reason, Chinese scholars understand the concept of inclusion either as a beautiful educational ideal and value pursuit, or an educational philosophy (Liu, 2007).

Nevertheless, in the 21st century, the concept of inclusive education has been further recognised both by the Chinese government and by the education administration. In addition, it has gradually become a guiding ideology for China’s basic education and special education reform.

Actually, the implementation of China’s Learning in Regular Classroom (LRC) policy reflects the characteristics of this preparatory model, which makes it possible for children with disabilities to be admitted to a general classroom. Three types of students with disabilities are attended to: 1) students with visual disabilities, 2) students with hearing disabilities, and 3) students with mild to moderate mental disabilities. In contrast, students with moderate to severe disabilities, multiple disabilities and other types of disabilities are still rejected by ordinary schools (Deng, 2013). However, the practice of LRC is much older than the LRC policy. In 1950, as a kind of folk – sponsored educational practice, rural primary schools in Dabashan, Sichuan, had forms of education and placement for receiving disabled children. In 1970, there were already records of deaf students graduating from ordinary schools in the northeast of China and Beijing. During the Chinese economic reform, some schools in the northeast of China began to place mentally handicapped children in ordinary classes (Piao, 2004; Xing, 2017).

Historically, in 1996, the State Education Commission and the China Disabled Persons’ Federation jointly published the “National Plan for the Implementation of the Ninth Five-Year Plan for Compulsory Education for Children with Disabilities in China,” and further clarified the role and status of LRC. The plan mentioned that China should “universally implement LRC, set up special classes for towns, set up special education centres in counties with more than 300,000 people, and accept more children with disabilities. Basically, form schools for LRC and special classes within the main body, and treat special education schools as the backbone in the compulsory education pattern of disabled children and adolescents” (Deng & Manset, 2000; Deng, Poon-Mcbrayer & Farnsworth, 2001; Liu & Jiang, 2008; McCabe, 2003; Qian, 2003).

In 2006, LRC was formally written in the revised Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China, article 19: “Ordinary schools should receive disabled children of school age and young people who have the ability to receive general education and to help them with their study and rehabilitation”. In 2008, LRC extended from compulsory education to all general education institutions including kindergartens, secondary schools, secondary vocational schools and higher education institutions (Li, 2015).

In 2010, the “Outline of the National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020)” is established, divided into “Special Education Development Plan (SEDP) First Session (2014-2016),” where “inclusive education” appears for first time in the national policy text, and “SEDP Second Session (2017-2020),” where the Chinese policy has begun to develop in the direction of considering a better quality (Jia, 2018).

Nowadays, the inclusive education development trend is mainly reflected in three aspects (Zhang & Zhu, 2018): (1) changing from moral assistance to humane care, (2) changing from isolated schools to social cooperation, and (3) changing from maintenance care to professional support.

Therefore, due to differences in politics, economy, culture and ethnicity, China’s “inclusive education” theory and practice have their own specific forms of presentation and still face challenges from the perspectives of concept, system and practice. There is still a certain distance from the goal of inclusive education in China’s learning in regular classroom. However, over the years, China’s “inclusive education” will develop better and better.

1.2. The concept of inclusive education in Canada, the USA, Europe and Australia

In China, the understanding of the concept of “inclusive education” is still mainly at the stage of introducing and analysing the “inclusive education” of Western inclusive education scholars.

In fact, in the 1990s, Europe’s citizen movements were generalised and intensified in favour of higher quality education and greater resources and public aid. In this context, the term inclusive education begins to be used. From the year 2000 onward is when, starting in the socially of more advanced countries of northern Europe (Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark among others), Australia, Canada and the USA, effective measures are put in place to favour inclusion in the classroom, equal opportunities and respect for differences. This trend is gradually spreading to other countries in the centre and south of the old continent (Casanova, 2011; Forlin, 2006; McCrimmon, 2015; Thomazet, 2009).

According to Soriano (2011), it is difficult to summarise the situation and position of the different Western countries regarding inclusion without falling into generalities. It can be said that, in general, and as shown by the approval of the different agreements and international documents by the Western countries, the tendency or the common objective is to achieve quality education for all students.

In addition, the implementation of inclusive education implies a deep reflection on the educational system as a whole. It implies a political will to change and assume some theoretical and methodological challenges in the educational level in which both students and teachers, parents and educational leaders are involved (Escribano & Martínez, 2013; Jardí et al., 2022; Rojas & Haya, 2020).

The interpretation of “inclusive education” in the “Policy Guidelines on Inclusive Education” published by UNESCO (2005) is often cited in Chinese journal articles where inclusive education is considered a process through increasing the participation of learning, culture and community to reduce exclusion within and outside the education system, and focus on and meet the diverse needs of all learners. Inclusive education is based on the consensus of all age-appropriate children and is committed to educating all children in a formal system. It involves changes and adjustments in educational content, educational pathways, educational structures and educational strategies. Inclusion involves responding appropriately to diverse learning needs in both formal and informal educational settings. Inclusive education is not a small issue about how to integrate some students into the dominant society. It is a way of examining how to reform the education system and other learning environments to accommodate the diversity of learners. The goal is to enable both teachers and students to embrace diversity and take it as an opportunity, as a rich learning environment, rather than a problem.

So, in order to compare the Western and the Chinese inclusive education concepts, the objective of this study is to identify the conception of inclusive education of primary school teachers, local or regional government officials and NGO workers from the regions of Guanxi, Sichuan, Chongqing and Tibet, as well as its weaknesses and strengths, while also observing its differences from the Western conception through the literature. This research was supported by the Education Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Reference of concession: 561600-EPP-1-1-CN-EP.

2. METHOD

According to the research objective, the mixed method is used in this research, so its purpose is to explain and interpret, to address a question at different levels and to explore a phenomenon related to inclusive education in China.

On the other hand, the qualitative method has allowed us to analyse certain factors in depth, taking into account different points of view (primary school teachers, local government officials and NGO workers). This method is used to help explain and interpret the findings of the quantitative study. A system of categories and subcategories has been created to analyse the information data.

2.1. Sample

The participants in all the instruments came from four regions in China: Guanxi, Sichuan, Chongqing and Tibet.

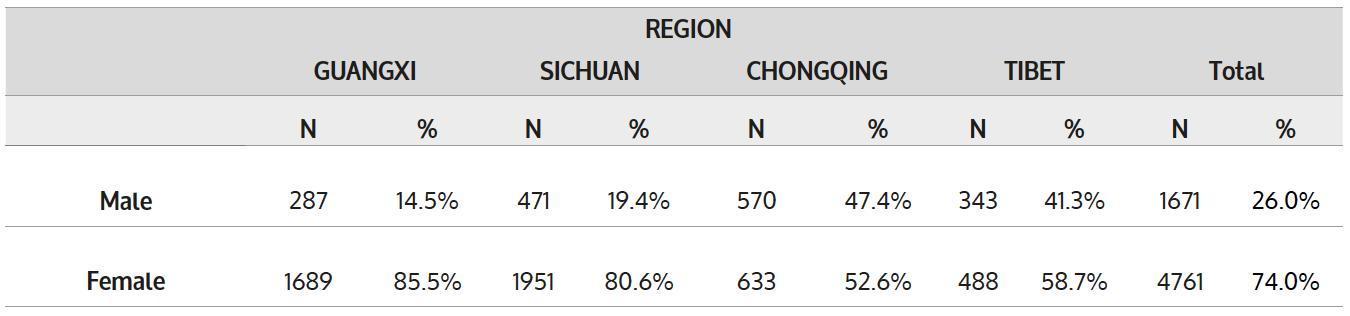

As for the characteristics of the primary school teachers’ sample who participated in the questionnaire (N=6432), regarding the gender variable, 26% were men and 74% were women (see table 1).

Table 1. Gender of the Primary school teachers who participated in the questionnaire

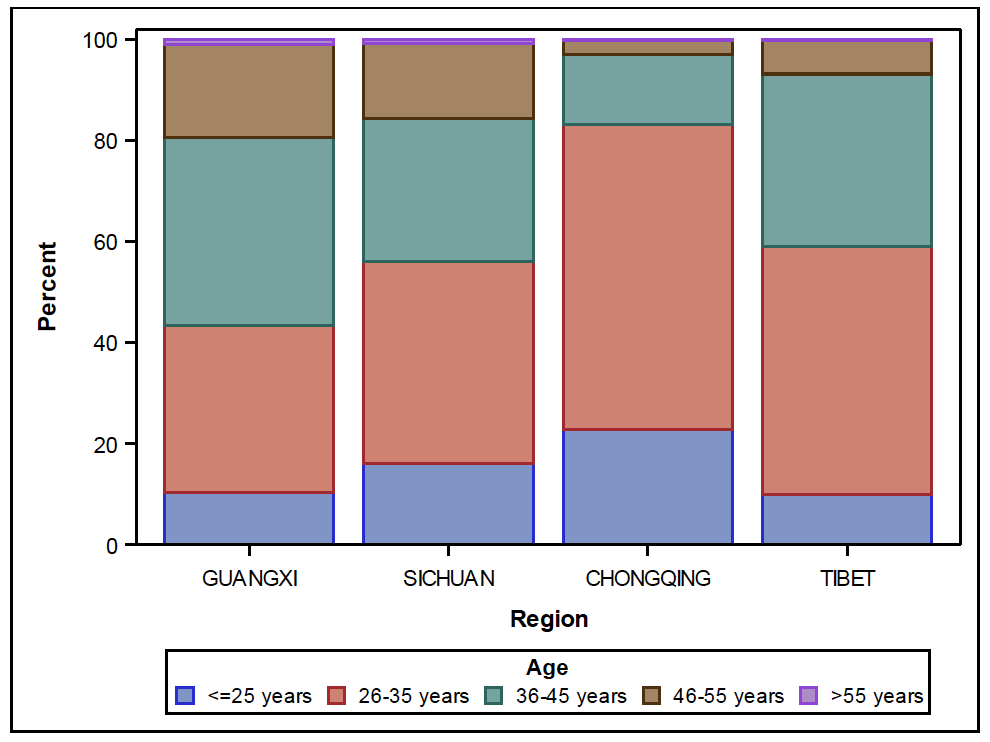

By age and region, we observed that the average of the primary school teachers’ sample was between 25 and 55 years (see graphic 1).

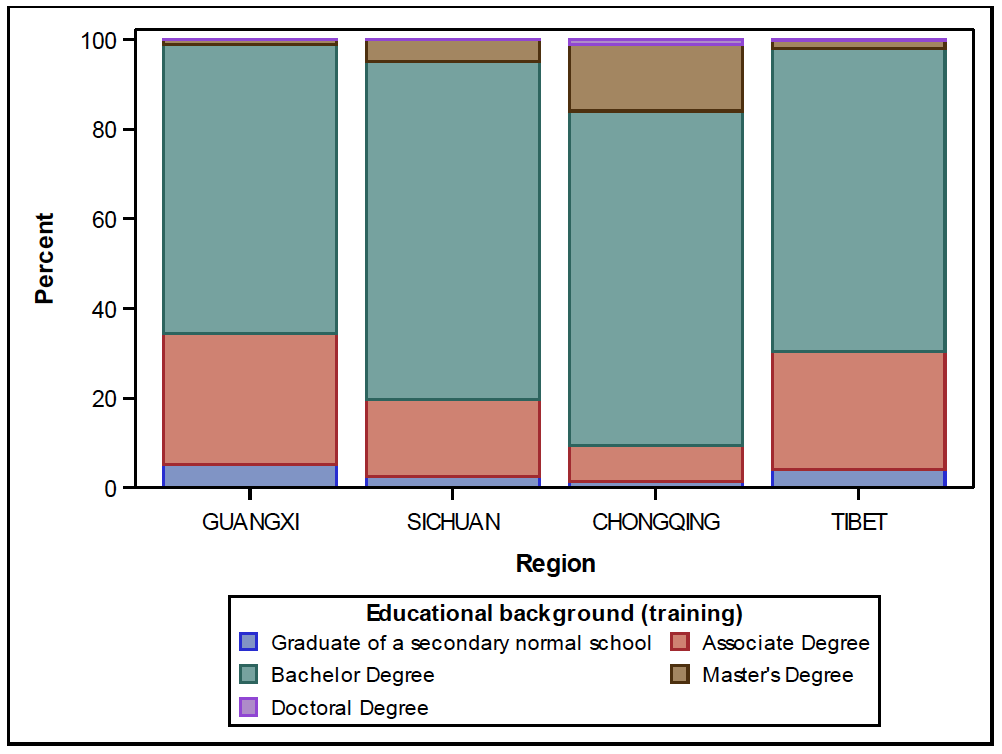

Within the sample, 3.4% were graduates in secondary school, 20.4% had an associate’s degree, 70.8% had a bachelor’s degree, 5.1% had a master’s degree and 0.3% had a doctorate (see graphic 2).

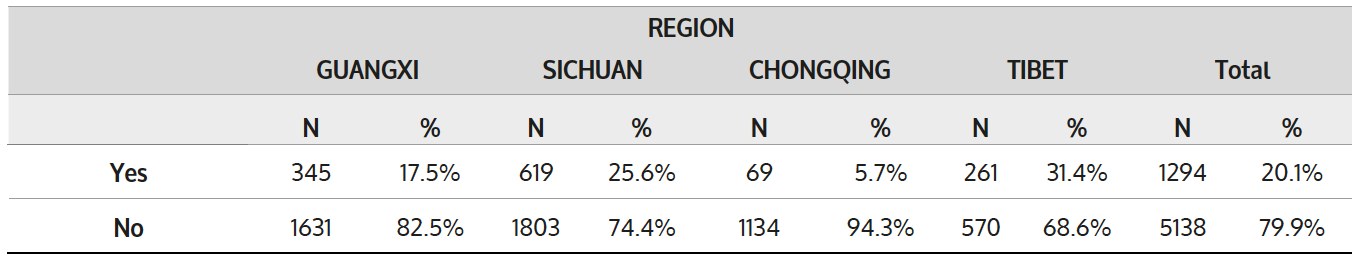

Only 20.1% of the sample had taken some type of inclusive education course during their initial training, while 79.9% had not had any type of inclusive education training (see table 2).

Table 2. Sample’s courses on inclusive education during initial training

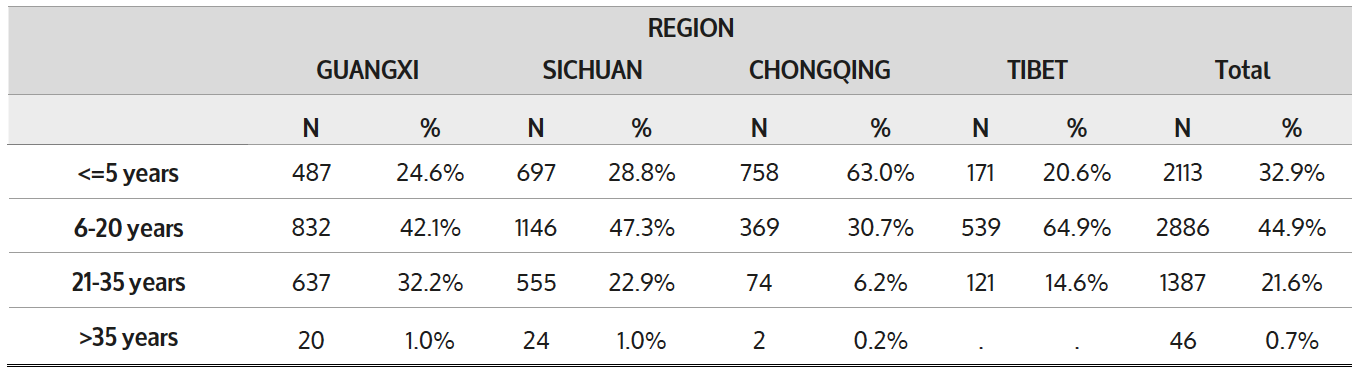

In addition, out of the teachers’ sample, 44.9% had had teaching experience of 6 to 20 years, while 32.9% had had less than 5 years of experience. Only 21.6% had had between 21 and 35 years (see table 3).

Table 3. Teaching experience of the teachers’ sample

2.2. Instruments

Questionnaire, interviews and focus groups were the instruments used to obtain data in this research.

2.2.1. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was composed of two parts: personal and professional data and items regarding the inclusion concept. Personal and professional data comprised 11 combined closed and open questions. The second part had 40 items that had to be answered through a scale (1=Never, 2=Occasionally, 3=Usually and 4=Always).

A total of 6,432 primary school teachers, 1,976 NGO workers and 4 local government officials answered the questionnaire. However, before the questionnaire was passed to the sample, 12 experts from European and Chinese universities revised the questionnaire according to three criteria – important, relevant and univocal – and it was adapted to the Chinese context. The general reliability of the questionnaire is an Alpha of 0.952.

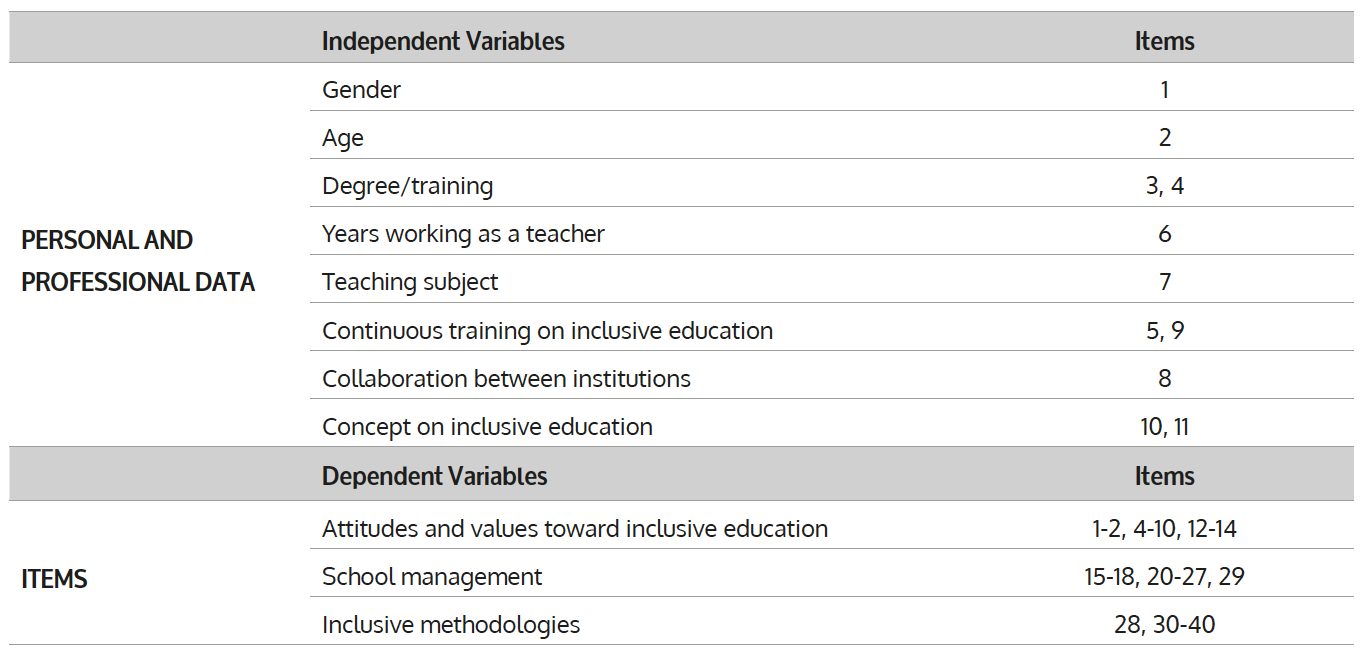

For this article, we have only taken into account the concept of educational inclusion, although the study was much broader and took into account other types of variables (see table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between parts of the questionnaire, variables and items

It is worth mentioning that due to low correlations or low discrimination power, items 3, 11 and 19 were excluded from the analysis. Items 13-14 were incorporated in the first dimension and item 29 in the second dimension, after the validation process.

2.2.2. Interview

Three semi-structured interviews were conducted, and references were reviewed. Some of the interview questions were: What changes are required in the current approach to increase equity and inclusion in the school? Could you identify the most important change in your local area to increase equity and inclusion? And what is the biggest barrier to that change?

Before the interview was passed, 12 experts from European and Chinese universities revised it according to two criteria —important and relevant— and it was adapted to the Chinese context.

In total, 20 primary school teachers (5 per region), 8 NGO workers (2 per region) and 8 local government officials (2 per region) participated in the interviews.

2.2.3. Focus group

In total, 32 people of the sample participated in the focus group. A guide was prepared where the principal and initial question was: How do Chinese schools implement inclusive education?

2.3. Procedure

The researchers were in charge of contacting the selected individuals and setting the day and time to respond to the questionnaire, which was done in the centres in the presence of one of the authors of this paper and in an average time of 15 minutes. The procedure for collecting data from the focus group and interviews was carried out during one month with the purpose of obtaining as much information as possible.

2.4. Data Analysis

To analyse the data from the questionnaire, the statistical analysis was performed by using the software SAS v9.4.

For each item, the following statistics were obtained: the percentage of response of each category (never, occasionally, usually and always); mean and standard deviation; the correlation between the items and the dimension; and the discrimination power.

A descriptive table with the summarised statistics was obtained for quantitative variables. Box plots were used for graphical representation and frequency tables and grouped bar plots were used to summarise personal and professional data, for each university and globally.

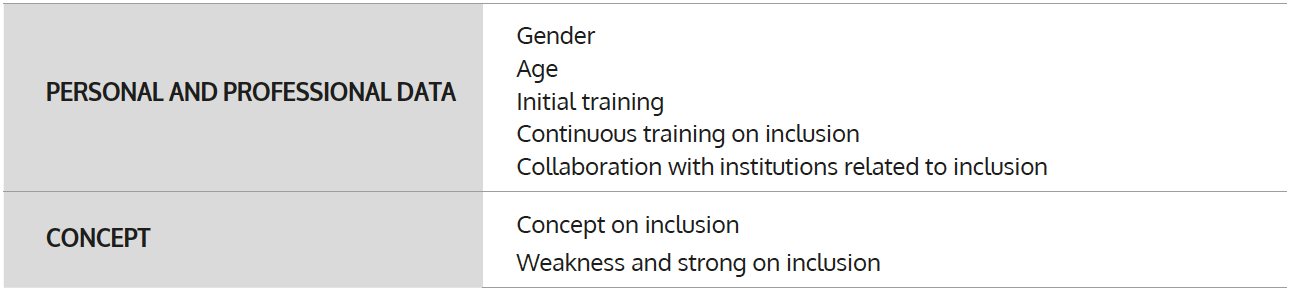

The qualitative data analysis from interviews and focus groups was conducted through a hermeneutic matrix (see table 5). Categories and sub-categories followed a mixed deductive-inductive process. The categories originated in theoretical framework and the sub-categories emerged from the field research and were incorporated into the matrix. The code of the categories and sub-categories was obtained through the MAXQDA software (version 17).

Table 5. Qualitative data analysis: Categories and sub-categories

3. RESULTS

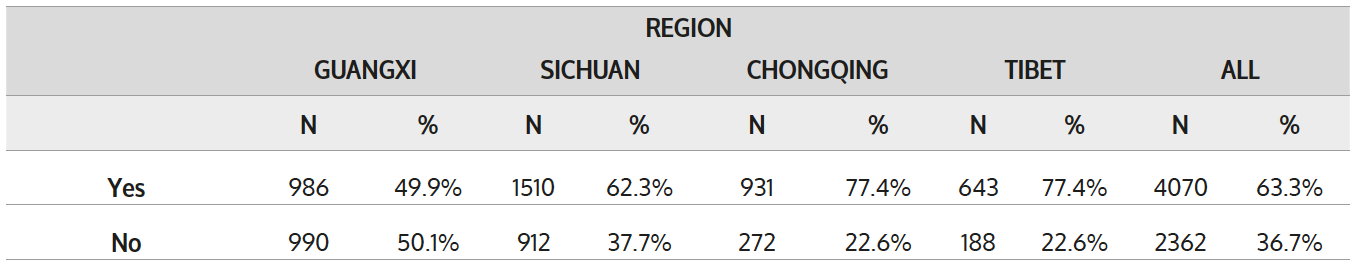

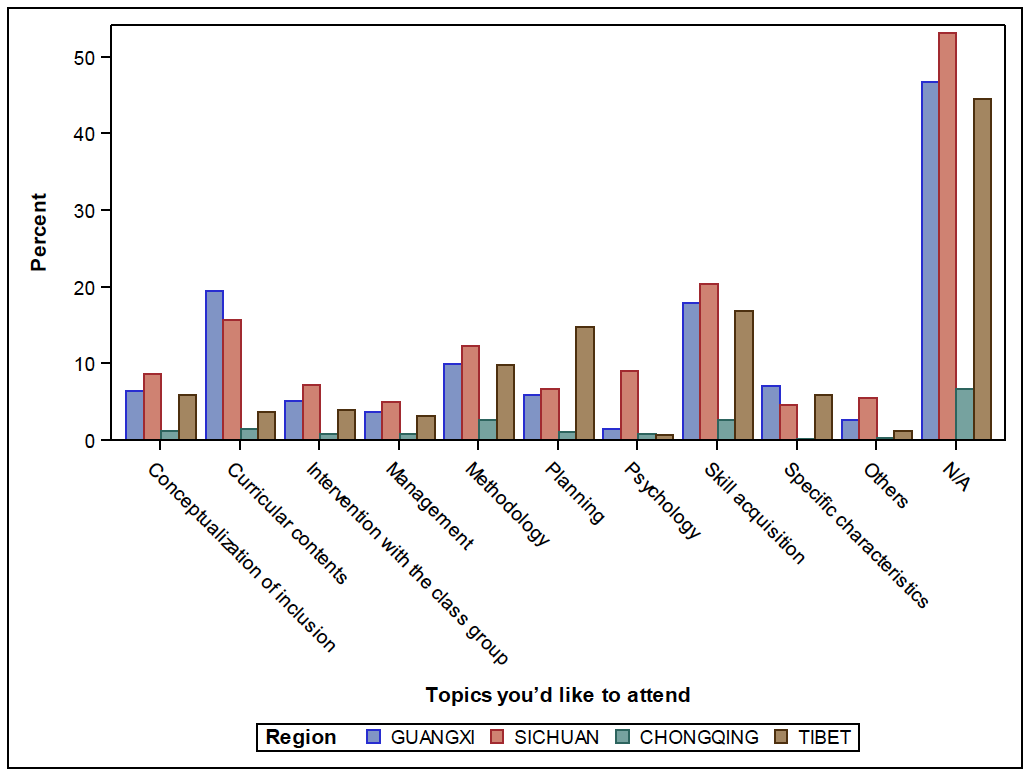

It is interesting to note that 63% of primary school teachers are willing to attend courses on inclusive education. The courses, as proposed by the teachers, that they would be willing to attend concern: acquisition of skills 15.2%, curricular content 11.4%, methodologies 9.1%, planning at 6.5% and concept of inclusion in education 6%, intervention on the group class 4.7%, specific characteristics 4.4%, psychology 4%, and management 3.4% (see table 6 and graphic 3).

Table 6. Primary school teachers of the sample willing to attend a course on inclusive education

Graphic 3. Sample’s educational background

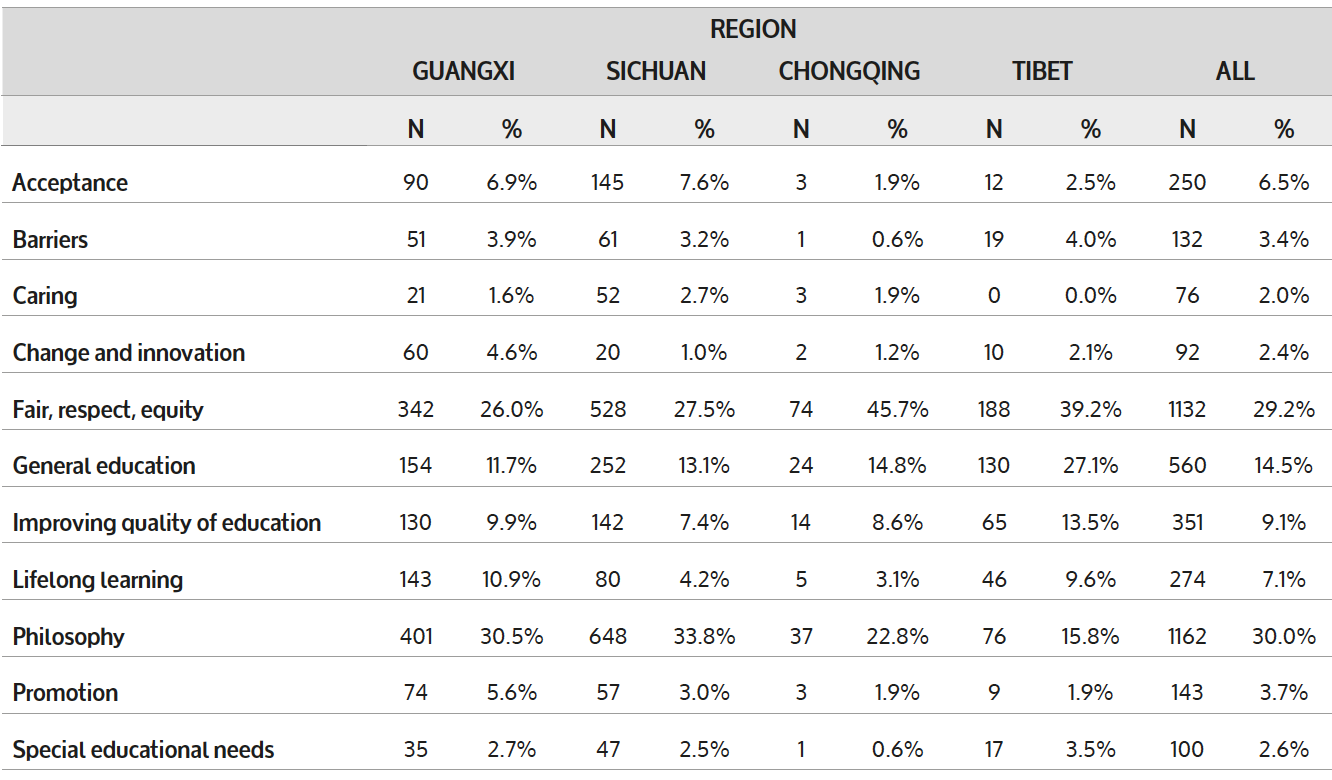

Regarding the teachers’ conception of inclusive education, it is interesting to mention that 30% speak of philosophy, 29.2% of justice, respect and equity, 14.5% of general education, 9.1% of improving the quality of education, 7.1% of learning throughout life, 6.5% of acceptance, 3.7% of promotion, 3.4% of barriers, 2.6% of special education needs (SEN), 2.4% of change and innovation and 2% of care (see table 7).

Table 7. Conception of inclusive education from regions

The aspects that teachers consider weaker in inclusive education are: 13.5% equipment, funds and resources, 13.2% difficulties to assist students with different personalities, 12.5% poor teacher training, 12% the education system does not facilitate inclusion, 10.7% teachers as professionals, 8.7% difficulties in classroom management, 6.8% non-efficiency, 6.3% lack of time, 5.8% not too adequate teaching methodologies, 5.6% size of a very large class, 5.5% unclear inclusion concept, 4.5% not applicable for all, 4.4% lack of collaboration with families, 4.2% evaluation focused on the final exam and 0.6% do not see disadvantages (see table 8).

Table 8. Inclusive education’s weaknesses

Regarding the aspects that teachers consider stronger in inclusive education, 62.7% think that the values, 22.5% the improvements and innovation in education, 19.9% the improvement of the professional development of the teacher, 16.5% the cooperation, participation and mutual help, and finally 1.6% do not seem to understand the inclusive education concept (see table 9).

Table 9. Inclusive education’s strengths

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As we have seen in the results section, 63% of the teachers of our sample see the need and would be willing to take courses on inclusive education, because, to date, only 20% of the sample has received some training. It should be noted that most of the Chinese individuals of the sample agree to acquiring new skills, not only methodological skills, but concerning how to treat students with disabilities.

However, the Chinese conception of inclusive education is far from the Western conception (for instance: European Commission, 2021; UNESCO, 2005 or SEND Code of Practice, 2015). In fact, positive values were consolidated in 62.7% of the interviewees, but without detailing the values on which they were based. Therefore, the Chinese people perceive inclusive education as a philosophical idea of justice, respect and fairness. Along these lines, we find a very philosophical but, at the same time, unclear idea of the concept of inclusion. While it is true that a part of the teachers considers that inclusive education brings improvements and innovation to education and improves the teachers’ professional development (although there is still a long way to go in these aspects), less than 17% mention the concepts of cooperation, participation and mutual aid. They are thus limiting the inclusion education concept only to teachers and equipment, and forgetting the fundamental role played by both students and families. Furthermore, some of the weaknesses do not only concern methodology or equipment, but collaboration between the whole educational community (including the families, students with or without SEN, Government workers and the community, that is, neighbours and services as police officers or firefighters, to name a few). In addition, only 3.4% mention the need to eliminate barriers (note the importance of removing both physical and psychological barriers) and only 2.6% mention individuals with SEN. These findings demonstrate the imperative need to train Chinese teachers in inclusive education and the need to expand the inclusive education concept beyond Confucius’s teaching because “teaching without discrimination” excludes the poorest and most marginalised members of society, whereas inclusive education means education for all, regardless of social class, and with the aim of creating a school for all. In fact, China’s LRC is a product of combining Western inclusive education and China’s special education, and an important way for China to promote inclusive education.

Nevertheless, the inclusive education concept is clear in the literature review, mainly in political implications: it does not reach school culture and practice. For this reason, active participation of the educational community is required, focusing on collective cooperation and high-quality education which affects an inclusive society at the same time. Of course, the implementation of inclusive education has become effective over the years. For instance, LRC has been implemented in all general education institutions (Li, 2015), not only with the purpose of “having a chance to learn”, but “learning well” (Jia, 2018). In fact, this point is reflected in an orientation to humanistic care, social cooperation and professional support (Zhang & Zhu, 2018). Therefore, it is clearly observed that Chinese teachers need training that does not only work on the concept of inclusive education. Instead, it should also focus on providing them with new skills, new methodologies, teaching them how to use and take advantage of the resources at their disposal, favour an active role of students and their families, and focus on all students, with or without SEN.

5. LIMITATIONS

Below we present the main limitations of this study: 1) lack of previous research studies on inclusive education in China; 2) given the large number of participants in the sample, we mainly relied on a questionnaire to collect the data; and 3) self-reported data based on focus groups and interviews may contain several potential sources of bias that must be taken into account. For instance, these biases may be due to the selective memory of the participants (remembering or not some experiences or events); attributing positive events and results to oneself but attributing the negative ones to external forces; as well as exaggeration in some answers.

Finally, the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Ainscow, M., Booth, T. & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. Routledge

Allan, J. & Slee, R. (2008). Doing Inclusive Education Research. Sense Publishers.

Artiles, A. & Dyson, A. (2005). Inclusive education in the globalization age. The promise of comparative cultural-historical analysis. In D. Mitchell (Ed.). Contextualizing Inclusive Education (pp. 37-62). Routledge.

Casanova, M.A (2011). CEE. Participación Educativa, 18, noviembre 2011, pp. 8-24.

Deng, M. & Manset, G. (2000). Analysis of the “learning in regular classrooms” movement in China. Mental Retardation, 38(2), 124-30.

Deng, M., Poon-Macbrayer K. F. & Farnsworth E. B. (2001). The development of special education in China, a sociocultural review. Remedial and Special Education, 22, 288-298.

Deng M. & Jing. S. (2013). Cong sui ban jiu du dao tong ban jiu du: guan yu quan na jiao yu ben du hua li lun de si kao (From leaning in regular classrooms to equal regular education: reflections on the localization of Inclusive Education in China. Chinese Journal of Special Education 8, 3-9.

Escribano, A. & Martínez, A. (2013). Inclusión Educativa y profesorado inclusivo. Madrid: Narcea.

European Commission (2021). Union of Equality: Strategy for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021-2030. Brussels. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:101:FIN#document1.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive Education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal Psychology of Education, 21(3), 265-277.

Huang, Z. C. (2001). Quan na jiao yu: 21 shi ji quan qiu jiao yu yan jiu xin ke ti (Inclusive education: A new topic in global education research in the 21st century). Global education, 1, 51-54.

Huang, Z. C. (2004a). Quan na jiao yu ---- guan zhu suo you xue sheng de xue xi he can yu (Inclusive education--- involving all children). Shanghai Education Publishing House.

Huang. Z. C. (2004b). Quan na jiao yu ---- guan zhu suo you xue sheng de xue xi he can yu (Inclusive education--- Focus on the learning and participation of all students). Shanghai Education Publishing House.

Jardí, A., Webster, R., Petreñas, C. & Puigdellívol, I. (2022). Building successful partnerships between teaching assistants and teachers: Which interpersonal factors matter? Teaching and Teacher Education, 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103523 .

Jia. L. S. (2018). Quan na jiao yu gai ge fa zhan fang shi shen shi--- ji yu yi da li xue xiao yi ti hua zheng ce yu wo guo sui ban jiu du zheng ce de kao cha (Examining the reform patterns of inclusive education--- based on Italy’s school integrated policy and China’s learning in regular classroom policy). Journal of Teacher Education, 5(2), 73-82.

Kavale, K. A. & Forness, S. R. (2000). History, rhetoric and reality. Analysis of the inclusion debate. Remedial and Special Education, 21(5), 279-296.

Kozleski, E., Artiles, A., Fletcher, T. & Engelbrecht, P. (2009). Understanding the dialectics of the local and the global in education for all: A comparative case study. International Critical Childhood Policy Studies, 2(1), 15-29.

Kozleski, E., Artiles, A. & Waitoller, F. (2011). Equity in Inclusive Education: Historical trajectories and theoretical commitments. In A. Artiles, E, Kozleski & Waitoller, F. (Eds.), Inclusive Education: Examining equity on five continents (pp. 1-14). Harvard Education Press.

Li, Y. (2009). Quan na jiao yu yu you jiao wu lei guan xi bian xi (Analyze the relationship of inclusive education and “Teaching without discrimination”). Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Educational Science), 3, 33-36.

Li. L. (2015). Wo guo sui ban jiu du zheng ce yan jin 30 nian: li cheng, kun jing yu dui ce (The Three-decade-long developments of China’s policy of inclusive education: the process, dilemma and strategies). Chinese Journal of Special Education, 10, 16-20.

Liu, C. & Jiang, Q. (2008). Teshujiaoyugailun (An introduction to special education). Huadongshifandaxuechubanshe (Huadong Normal University Press).

Liu, S.S. (2007). Quan na jiao yu dao lun (The introduction of Inclusive Education). Huazhong Normal University Press.

McCabe, H. (2003). The beginnings of inclusion in the People’s Republic of China. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 28(1), 16-22.

McCrimmon, A.W. (2015). Inclusive Education in Canada: Issues in Teacher Preparation. Intervention in School and Clinic, 50(4), 234-237.

Piao. Y.X (2004). Rong he yusui ban jiu du (Integration and LRC). Educational Research and Experiment, 4.

Qian, L. (2003). Quannajiaoyuzaizhongguoshishizhishexiang The implementation and vision of inclusive education in China. QuanqiuJiaoyuZhanwang (Global Education), 5, 45-50.

Rojas, S. & Haya, I. (2020): Inclusive research, learning disabilities, and inquiry and reflection as training tools: a study on experiences from Spain. Disability and Society, http://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1779038.

Singh, R. (2009). Meeting the challenge of inclusion: From isolation to collaboration. In Alur, M. & Timmons, V. (Eds.), Inclusive Education Across Cultures: Crossing boundaries, sharing ideas (pp. 12-29). Sage.

Soriano, V. (2011). CEE Participación Educativa, 18, noviembre 2011, pp. 8-24.

Special Education Needs and Disability (SEND) Code of Practice: 0 to 25 years (2015): Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/ SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf . Accessed 20/11/2018.

Thomazet, S. (2009). From integration to inclusive education: does changing the terms improve practice? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(6), 553-563, http://doi.org/10.1080/13603110801923476 .

UNESCO (2005). Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All. UNESCO.

Xing, S. (2017). La situación actual de la educación inclusiva en China. Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació,10(2), 1-14. http://doi.org/10.1344/reire2017.10.219094.

Yang, P. J. (1980). Lunyuyizhu (Analects of Confucius translation). Zhonghua Book Company.

Zhang. T. & Zhu. F. Y. (2018). Te shu jiao yu nei han fa zhan de zou xian yu shi jian yi tuo (The trend of and practical support for the connotative development of special education). Chinese Journal of Special Education, 3 , 2-8.